Pain Management in Long-Term Care Communities: A Quality Improvement Initiative

Affiliations: 1Joan and Sanford I. Weill Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY 2New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY 3Brookdale Senior Living, Brentwood, TN 4Med-IQ LLC, Baltimore, MD 5Center for Health Care Strategies, New York University Langone School of Medicine, New York, NY

Abstract: Pain is underrecognized and undertreated in the long-term care (LTC) setting. To improve the management of pain for LTC residents, the authors implemented a quality improvement (QI) initiative at one LTC facility. They conducted a needs assessment to identify areas for improvement and designed a 2-hour educational workshop for facility staff and local clinicians. Participants were asked to complete a survey before and after the workshop, which showed significant improvement in their knowledge of pain management and confidence in their ability to recognize and manage residents’ pain. To measure the effectiveness of the QI initiative, the authors performed a chart review at baseline and at 3 and 8 months after the workshop and evaluated relevant indicators of adequate pain assessment and management. The post-workshop chart reviews showed significant improvement in how consistently employees documented pain characteristics (ie, location, intensity, duration) in resident charts and in their use of targeted pain assessments for residents with cognitive dysfunction. The proportion of charts that included a documented plan for pain assessment was high at baseline and remained stable throughout the study. Overall, the findings suggest a QI initiative is an effective way to improve pain care practices in the LTC setting.

Project Pearls

• Implementation of a QI initiative can improve delivery of pain management performance standards for LTC residents.

• To achieve sustained improvement, an educational approach with consistent implementation of multidisciplinary activities is needed.

• Additional areas of educational need can be identified with repeated assessments of performance measures over time.

Key words: Pain management, quality improvement.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

An estimated 45% to 80% of older adults in long-term care (LTC) facilities experience significant chronic pain.1 Despite standards from the Joint Commission and other organizations that emphasize the right of patients to receive “appropriate assessment and management of pain,” pain in LTC residents is underrecognized and undertreated.2-6 Poorly managed pain negatively affects physical and mental health and impairs the overall quality of life in this vulnerable population.1,6-10 In addition, the consequences of untreated or undertreated pain further burden healthcare resources.1

The high prevalence of disability, dementia, comorbidities, and general communication difficulties among nursing home residents complicate efforts to assess and manage pain effectively. AMDA–The Society for Post-Acute and Long Term Care Medicine has developed clinical practice guidelines that seek to address barriers to optimal pain management in the LTC setting.11,12 However, systemic barriers such as drug costs, formulary restrictions, staffing challenges, and the lack of care coordination among health professionals make it difficult to apply the guidelines consistently.13

Studies show quality improvement (QI) initiatives can be effective tools for promoting adherence to treatment guidelines and other evidence-based practices. Boyle and colleagues13 conducted a series of continuing medical education (CME) workshops on diabetes care for clinical staff at two LTC facilities and subsequently observed significant improvement in various measures of resident health, including glycemic control. A well-designed QI program begins with a systematic evaluation of processes at every level to identify steps that may contribute to performance gaps or inconsistencies in care. The team then develops and implements a strategy for improving existing processes and establishes a mechanism to test the real and anticipated effects of changes to the system.14,15

To investigate barriers to optimal pain management in LTC and help facilities implement strategies for overcoming these barriers, members of an accredited CME provider collaborated with representatives from a national consortium of LTC communities to design, implement, and evaluate a CME QI initiative for pain management. Our goal was to improve the ability of caregivers to recognize, assess, and manage pain in elderly patients according to evidence-based guidelines. We used various mechanisms to measure changes in caregiver confidence and performance after the educational opportunities.

Methods

Med-IQ, LLC, a company that provides continuing education opportunities for physicians, nurses, and pharmacists and is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, coordinated a four-phase QI initiative to improve pain management for residents at Broadway Plaza at Cityview in Forth Worth, TX. Broadway Plaza provides independent living, assisted living, or skilled nursing care for seniors and is part of a nationwide network of LTC communities owned and operated by Brookdale Senior Living. Because this was a QI initiative and all data collected for workshop participants and residents were de-identified, we did not seek approval from an Institutional Review Board, however, the study’s objectives were communicated to all workshop participants.16

Development and Implementation

The study was conducted from April 2012 through March 2013. During phase 1 (needs assessment), we conducted focus group interviews among facility staff members and a retrospective review of resident charts selected at random to obtain qualitative and quantitative information about the facility’s pain management practices. The baseline information was evaluated and used to develop an educational intervention with specific learning objectives (Table 1). The workshops were open to all facility employees and to healthcare professionals from the surrounding community, some of whom also worked with residents at Broadway Plaza at Cityview.

During phase 2 (educational intervention), participants attended one of three identical 120-minute live continuing education/CME–certified workshops. Prior to the workshop, they were required to complete a survey about pain management, consisting of two confidence questions and four knowledge questions. The confidence questions used a four-part Likert scale with answer choices being “not at all confident,” “somewhat confident,” “moderately confident,” and “extremely confident.” The knowledge questions were multiple choice and had only one correct response. The same survey was administered again immediately after the workshop.

Phase 3 (evaluation) consisted of two steps. To measure the effectiveness of the educational intervention at meeting the learning objectives, we compared baseline responses to the survey with post-intervention responses. We also conducted chart reviews at 3 months and 8 months after the workshop to assess for changes in quality performance measures for pain management.17-19

In phase 4 (reinforcement), we sought to maximize the effect of the QI initiative by disseminating a 1.5-credit CME-certified publication emphasizing key lessons of the initiative. Findings from the evaluation stage were used to tailor the CME publication, which was distributed 6 months after the end of the last workshop.

Data Analysis

For the survey data, the participant served as the unit of analysis. Chi-square and t-tests were used to compare responses to the pre-workshop survey versus the immediate post-workshop survey for the 68 participants who completed both questionnaires.

For the chart review, the resident chart served as the primary unit of analysis. To assess the short-term effects of the intervention, baseline charts were compared with charts 3 months after training. To assess long-term effects, we compared baseline charts with charts 8 months after training. For each chart review period, we used the single most recent pain assessment record to measure changes in pain assessment practices; and we used documentation of pain management strategies and interventions for up to 3 months’ prior to chart abstraction to measure changes in how resident pain was handled. Because the charts we assessed at each time point belonged to different individuals, analyses are based on unlinked chart review data. We compared categorical data using nonparametric tests (eg, chi-square tests). For outcomes measured using continuous scales, we calculated means and compared them with independent t-tests. We considered a result statistically significant if the probability value was less than 0.05.

Results

During the study period, 111 staff members at Broadway Plaza were eligible to attend the workshops. A total of 89 individuals participated in the QI initiative: 34 nurses, 23 certified nursing assistants, 11 pharmacists, 9 administrators, 6 physicians, 3 nurse practitioners, and 3 certified medical assistants. When the study was conducted, the facility had approximately 88 residents. Overall, we reviewed charts for 142 unique residents: 45 charts at baseline, 47 at 3 months’ post-intervention, and 50 at 8 months’ postintervention. The mean age of the residents was similar at each assessment (mean range, 84-87 years), and most residents were women (range, 69%-79%). The mean length of stay significantly varied from baseline to 3 months (128 days vs 311 days, respectively; P=.031) and from baseline to 8 months (128 days vs 419 days, respectively; P=.002).

Survey Findings

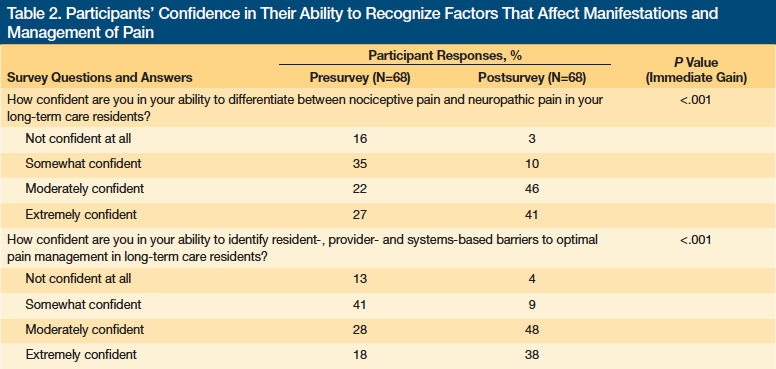

Approximately three-quarters of workshop participants (76%) completed both the pretest and posttest surveys. Survey responses showed significantly more participants were confident they could differentiate between nociceptive and neuropathic pain among LTC residents and identify barriers to providing residents with optimal pain management immediately after the intervention (Table 2). The percentage of participants with no confidence in their ability to differentiate between nociceptive and neuropathic pain was 16% before the workshops and dropped to 3% after the workshops (P<.001). The percentage of clinic staff with no confidence in their ability to identify barriers to optimal pain management in LTC residents was 13% before the workshops and declined to 4% afterward (P<.001). In contrast, the percentage of participants who selected moderate to extreme confidence for each question increased by approximately 40% after the workshops.

Only 70% of participants (n=47) answered at least three of the four knowledge questions. In the pretest, the small percentage of correct responses to three questions (range, 16%-36%) indicated a low level of baseline knowledge (Table 3). The posttest showed significant increases in the percentage of participants who correctly answered a question about potential causes of chronic pain in older adults (P<.001) and in the percentage who could accurately identify instruments used to measure the effect of pain on cognitive and psychological function (P=.015). From pretest to posttest, we observed no statistical improvement in the percentage of participants who indicated the correct treatment option for pain nonresponsive to opioids. The only knowledge question to earn a high rate of correct responses before and after the intervention was a case study.

Performance Data

We used resident charts to compare pain management practices at 3 months and 8 months after the intervention with practices at baseline. Charts were reviewed to see whether they contained a plan for pain assessment: daily assessments of pain in verbal and nonverbal patients, characterized according to pain duration, location, and intensity; and documentation of how pain was evaluated and managed.

Pain assessments. At baseline and postintervention, every chart reviewed included a pain assessment plan and daily pain assessments. At baseline, 82% of charts indicated that a physical evaluation was performed to determine the cause of pain, and this rate was not significantly different at the two follow-up assessments. At each assessment period, most charts documented the type of pain; however, the likelihood of different types of pain being reported changed over time. The percentage of charts reporting only neuropathic pain increased from 44% at baseline to 81% at 3 months and 84% at 8 months. The percentage of charts in which only nociceptive pain was reported declined from 22% at baseline to 0% at 3 months and 7% at 8 months. At baseline, 31% of charts reported mixed pain types, which declined to 10% at 3 months and 9% at 8 months.

Throughout the study, location of pain was the most commonly documented pain characteristic. Pain location was recorded in 67% of charts at baseline and at 3 months, whereas 98% of charts at 8 months identified pain location, reflecting a significant increase (P<.001). The percentage of charts documenting pain intensity also increased significantly from baseline to 3 months (33% vs 62%, respectively; P=.006) and from baseline to 8 months (33% vs 96%, respectively; P<.001). The increase from 3 to 8 months is also significant (P<.001). Before the intervention, a descriptive scale was used more often than a numerical score to measure pain intensity (42% vs 29%, respectively). Use of numerical scoring to measure pain intensity was significantly more common at 3 and 8 months (81% and 80%, respectively; P<.001 for both). Only 16% of charts at 8 months used a descriptive scale (P=.005).

Only 4% of the charts reviewed at baseline included duration of pain in the assessment. This rate increased to 45% at 3 months (P<.001) before declining to 34% at 8 months, which was still significantly better than baseline (P<.001). Overall, a greater proportion of charts documented all three pain characteristics at 3 and 8 months than at baseline (32% vs 32% vs 2%, respectively). At all three assessment periods, a minority of charts noted how pain affected the patient’s function, quality of life, or both. This did not change significantly over the course of the study.

Assessing pain in residents with cofounding factors. More than two-thirds of charts for each assessment period indicated that the patient was recently evaluated for depression. In addition, 25% of charts documented cognitive dysfunction at baseline compared with 22% at 3 months and 43% at 8 months. Charts showed that nearly all residents with cognitive dysfunction could communicate verbally, and we observed significant changes in the staff’s use of targeted pain assessment tools among these residents. From baseline to 3 months’ post-intervention, use of the Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors With Limited Ability to Communicate (PACSLAC) tool increased significantly from 0% to 90% (P<.001). Although use of the Abbey Pain Scale went from 0% at baseline to 30% at 3 months, the increase was not statistically significant. At 8 months’ postintervention, however, charts indicated no use of the PACSLAC tool and Abbey Pain Scale. Instead, the use of other, nonspecified tools had increased significantly from baseline to 8 months (36% vs 86%, respectively; P=.013).

A greater percentage of charts documented nonverbal indicators of pain at 8 months than at baseline (54% vs 30%, respectively; P=.024). The increase at 8 months remained significant compared with baseline even after we restricted the analysis to charts in which cognitive dysfunction was noted (95% vs 56%, respectively; P=.019).

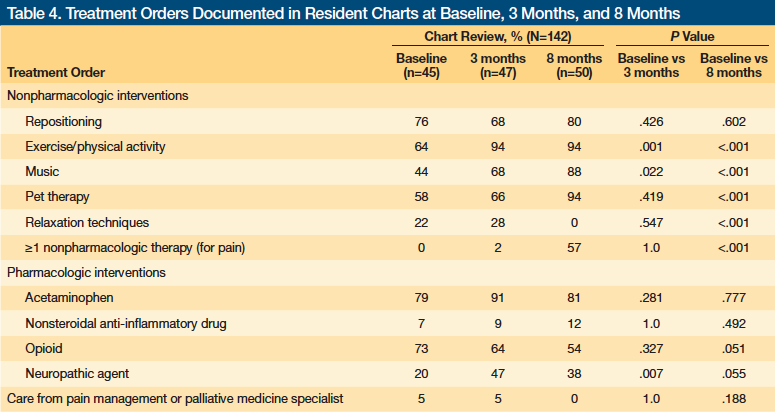

Change in interventions. Use of nonpharmacologic interventions remained high throughout the study, but charts at baseline and 3 months rarely indicated that these interventions were being used to help manage pain (Table 4). At 8 months, however, 57% of charts requesting a nonpharmacologic intervention noted that it was for pain management (P<.001).

During each assessment period, most residents had received acetaminophen to treat pain and more than half the charts included a current order for an opioid agent to treat pain. Most of these charts indicated “as-needed dosing,” with no significant differences in the dosing schedule between the assessment periods. However, from baseline to 8 months, the percentage of charts containing orders for opioid agents declined from 73% to 54%. We also observed a significant increase from baseline to 3 months in the proportion of residents with a current order for a neuropathic agent to treat pain (20% vs 47%, respectively; P=.007). This dropped to 38% at 8 months, however, and no longer represented a significant increase from baseline. Finally, the results showed that no more than 5% of residents received care from a pain management or palliative medicine specialist at any of the three assessment periods. We thought we might see an increase in referral for complicated pain management problems but this did not happen. It may be that complicated pain management problems did not occur during the observation period, which would also be a reason why so few patients were seen by a pain specialist.

Discussion

QI initiatives involve conducting a formal analysis of a predefined aspect of care and, based on those results, developing a systemic plan to improve care. The basic goal of a QI initiative is to improve patient care by eliminating the gap between daily clinical practices and evidence-based practices.20 Many barriers exist to providing optimal pain management in the LTC setting that operate on a staff level, facility level, patient level, and even a community level.

Jones and colleagues21 had limited success using an educational initiative to improve pain management at 12 US nursing homes. Through surveys and focus groups, they identified communication difficulties between different levels of staff (nursing assistants, nurses, and physicians) as an obstacle to improving knowledge. To ensure the success of our QI initiative, we felt it was essential to engage clinicians in planning, implementing, and assessing our QI initiative. We made sure to address several of the concerns clinicians identified in the pre-planning focus group in the educational initiative.

The QI initiative we implemented led to significant improvement in the ability of clinic staff to recognize and assess pain in residents of one LTC facility. Patient charts reflected more and better documentation of pain characteristics and greater reliance on numerical pain scores and targeted pain assessment tools, particularly when evaluating pain in residents with cognitive dysfunction. After the workshop, participants were significantly more confident in their ability to recognize and assess pain in LTC residents. Although the knowledge survey showed participants knew more about pain management after the educational intervention than before, the posttest results revealed several deficiencies in knowledge, indicating a need for ongoing education.

Evaluating the effect of pain on physical, psychosocial, and cognitive functioning is an important component of a comprehensive pain assessment. We found a minority of charts included documentation of how pain affected function or quality of life, and this did not change significantly after the intervention, indicating the need for more education, improvement in the reporting process, or both.

Patient obstacles to providing effective pain management include a reluctance among residents to report pain and comorbid conditions such as cognitive dysfunction or speech impairment, which may hinder residents’ ability to recall or communicate their pain experience.21,22 We saw sustained improvement in documentation of nonverbal indicators of pain after the QI initiative. However, the use of PACSLAC and Abbey Pain scales to measure pain in dementia patients increased from baseline to 3 months and then dropped back to 0% for both at 8 months. This suggests more education is needed on managing pain in this subgroup of residents.

Short-term improvement after a behavioral intervention followed by a decline back to baseline levels is not uncommon,23,24 and brief interventions without ongoing reinforcement are unlikely to yield lasting gains. In addition, the high staff turnover at nursing homes compromises the long-term effectiveness of a successful QI initiative.5

One intent of the workshop was to educate participants about the evidence underlying nonpharmacological approaches to pain management. We also described modalities appropriate for use in the LTC setting. At the facility where we carried out the QI initiative, use of nonpharmacologic interventions was high at baseline, and this was maintained throughout the study period. The 3-month chart review showed a significant increase in the use of exercise or physical activity from baseline, and this increase was sustained at 8 months. We partly attribute this change to the educational intervention.

We found the overall rate of pharmacologic treatment relatively unchanged throughout the study, yet the charts showed a decrease in the use of opioid and an increase in the use of neuropathic agents. Although the intervention was designed to increase the number of residents with pain who received appropriate treatment, it was not intended to influence the choice of analgesic, and thus it seems unlikely the intervention had an effect on analgesic prescribing.

Six months after the workshop and 2 months before the final outcomes assessment, we disseminated a 1.5-credit CME publication designed to reinforce important lessons of the workshop. We also conducted a series of webinars explaining the project results to physicians, nurses, and other care staff at Brookdale Senior Living. We encouraged participants to use the tools and strategies discussed in the CME component and the Webinars to achieve optimal pain management. The effect of the CME component on 8-month outcomes is unclear; some end points showed improvement from 3 to 8 months, whereas others showed a decline.

Study Limitations

This study had several limitations, including the small sample size and lack of a control group. Also, the high baseline performance on some measures suggests factors other than QI participation may contribute to staff performance levels. Differences between each chart review period in documentation of the proportion of patients experiencing specific types of pain, the proportion of patients documented as having cognitive impairment, and the proportion of patients assessed for depression may reflect differences in the patient population for each phase, rather than differences in documenting practices. In addition, the retrospective nature of the chart review means changes may reflect differences in charting practices rather than modified behavior.

The review of pain assessment practices at baseline, 3 months, and 8 months was based on a single day of data (the most recent assessment). Some assessments may have been performed by staff who did not participate in the educational objective, which limits the ability to measure the direct effect of the educational objective on outcomes. Obviously having all staff participate in the QI initiative would allow a more reliable assessment of its effectiveness at improving pain management in the LTC. Finally, the decision to let non-staff participate in the educational objectives means no conclusions can be drawn about the relationship between survey responses and charting practices.

Conclusion

We used a QI initiative to identify areas in need of improvement at one LTC facility and developed an educational workshop that targeted facility staff. The workshop produced significant gains in participants’ confidence in their ability to recognize factors affecting the manifestations of pain among LTC patients and in their knowledge of pain management. The intervention was associated with significant improvements in how staff documented key pain characteristics in residents’ charts and in the use of targeted pain assessments for residents with cognitive dysfunction. The results of this study support the value of using QI initiatives to address inadequate pain management in the LTC setting but also reflect the need for ongoing reinforcement of the learning objectives to sustain improvement.

Acknowledgments: This project was planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health and Med-IQ. The authors thank Rita Vann and the staff of Brookdale Senior Living communities involved in this project for their participation in the focus groups and education; Petrina Brumfield, Donna Echols, Carol Johnson, and Veronica Rogers for data collection; Whitney Stevens-Dollar for project management; LaWanda Abernathy for participant recruitment; Kenny Khoo for data management; Amy Sison and Mary Catherine Downes for outcomes management, Samantha Roberts for CME coordination; Christine Gray and Bianca Perri for assistance with data analysis; and Rebecca Julian for editorial assistance.

Funding: This activity was supported by an educational grant from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., provided by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The funding source had no role in the execution, analysis, or development of the resulting manuscript associated with this initiative.

References

1. AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons. The management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(suppl 6):S205-S224.

2. The Joint Commission website. Facts about pain management. www.jointcommission.org/topics/pain_management.aspx. Published February 4, 2014. Accessed January 30, 2015.

3. Zanocchi M. Chronic pain in a sample of nursing home residents: prevalence, characteristics, influence on quality of life (QoL). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;47(1):121-128.

4. Martin CM. Nursing facilities face a new challenge: better treatment of pain. Consult Pharm. 2009;24(7):494-503.

5. Jones KR, Fink R, Pepper G, et al. Improving nursing home staff knowledge and attitudes about pain. Gerontologist. 2004;44(4):469-478.

6. Planton J, Edlund BJ. Regulatory components for treating persistent pain in long-term care. J Gerontol Nurs. 2010;36(4):49-56.

7. Ferrell BA. The management of pain in long-term care. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(4):240-243.

8. Herr K. Chronic pain: challenges and assessment strategies. J Gerontol Nurs. 2002;28(1):20-27.

9. Parmelee PA, Katz IR, Lawton MP. The relation of pain to depression among institutionalized aged. J Gerontol. 1991;46(1):15-21.

10. Teno JM, Kabumoto G, Wetle T, et al. Daily pain that was excruciating at some time in the previous week: prevalence, characteristics, and outcomes in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):762-767.

11. Hadjistavropoulos T, Herr K, Turk DC, et al. An interdisciplinary expert consensus statement on assessment of pain in older persons. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(suppl 1):S1-S43.

12. AMDA. Pain Management Clinical Practice Guideline. www.amda.com. Updated 2012. Accessed January 14, 2015.

13. Boyle PJ, O’Neil KW, Berry CA, Stowell SA, Miller SC. Improving diabetes care and patient outcomes in skilled-care communities: successes and lessons from a quality improvement initiative. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(5):340-344.

14. Lotstein D, Seid M, Ricci K, et al. Using quality improvement methods to improve public health emergency preparedness: PREPARE for Pandemic Influenza. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(5):w328-w339.

15. Lighter D, Fair DC. Quality Management in Health Care: Principles and Methods. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2004.

16. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 45: Public Welfare: Department of Health and Human Services, Part 46: Protection of Human Subjects. www.hhs.gov/ohrp/policy/ohrpregulations.pdf. Updated January 15, 2009. Accessed January 30, 2015.

17. National Quality Measures Clearinghouse. US Department of Health & Human Services website. www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov. Accessed January 30, 2015.

18. National Quality Forum website. www.qualityforum.org/Measures_List.aspx. Accessed January 30, 2015.

19. Physician Quality Reporting System. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. www.cms.gov/pqri. Updated April 20, 2014. Accessed January 14, 2015.

20. Elmi J. CDC coffee break: evaluating quality improvement initiatives: an example of a high blood pressure clinical QI intervention. www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/cb_december_2012.pdf. Published December 11, 2012. Accessed January 14, 2015.

21. Jones KR, Fink R, Vojir C, et al. Translation research in long-term care: improving pain management in nursing homes. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1(suppl 1):S13-S20.

22. Buffum MD, Hutt E, Chang VT, Craine MH, Snow AL. Cognitive impairment and pain management: review of issues and challenges. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44(2):315-330.

23. Xakellis GC, Frantz RA, Harvey P. Translating pressure ulcer guidelines into practice: it’s harder than it sounds. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2001;14:249-256,258.

24. Laiteerapong N, Keh CE, Naylor KB, et al. A resident-led quality improvement initiative to improve obesity screening. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26:315-322.

Disclosures: Dr. Reid was supported at the time of this work by a grant from the National Institutes of Health: An Edward R. Roybal Center for Translational Research on Aging Award (P30AG22845) and served as a consultant to Endo Pharmaceuticals during the past year. The other authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to: M. Carrington Reid, MD, PhD, Division of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, 525 East 68th Street, #39, New York, NY 10065;