Oral Health Education for Nursing Home Staff

This study investigated the way oral health protocols are approached in nursing homes (NHs). A cross-sectional comparison retrospective chart review was conducted regarding dental referrals, and pre- and post-surveys of nursing staff with the implementation of an oral assessment educational module based on the Minimum Data Set (MDS) were performed. The education module was designed for NH staff to outline how daily oral assessments and oral care are performed and when referrals for subsequent dental treatment are necessary. Results suggest education related to identifying oral health conditions and completing the MDS 3.0 dental section helps NH staff increase their knowledge and perceptions of providing oral care and assessments as well as making referrals to oral health care providers.

Key words: oral health care, oral hygiene education, minimum data set, decision tree

Oral health protocols in nursing homes (NHs) are challenging. Insufficient monitoring of residents’ oral self-care, staff confusion concerning oral assessment responsibilities, and overall resident resistance to oral care assessments all contribute to the decline of oral health in this setting.1-3 Oral health protocols must be implemented efficiently and affordably, as residents often have limited ability to seek dental treatment, and facilities frequently face issues of understaffing and minimal oral hygiene resources.4 Increasingly, the aging population is maintaining their natural dentition, which requires NHs to address oral health in order to minimize and prevent dental disease and provide expedient treatment for dental problems.4,5

When implementing oral health protocols that meet standards of care for geriatric residents, facilities must find a sustainable solution. Standards of care include daily assessments and cleaning of all oral structures, full and partial denture maintenance, and oral care capability assesments of the resident.6 Staff should tailor the oral hygiene routine to the functional abilities and oral status of residents. These standards should be implemented in every long-term care facility (LTCF) and outline the resident’s oral care needs, including tooth brushing and denture care.

Several studies have reported a desire by staff for more leadership and education in meeting the challenges of implementing oral health protocols for their residents. Willumsen et al1 found that NH staff felt oral health knowledge was important in providing oral care, but only one quarter of the individuals in the study felt they had adequate knowledge to provide oral care in practical day-to-day situations. Miegel and Wachtel4 outlined the lack of communication and leadership in the dental profession and showed the frustration of nurses with the lack of dental input in the treatment of oral needs in NH settings.

Another study found that 40% of NH staff wanted more oral education: 25% training by a dental professional, 21% practical training, and 13% theoretical training.2 This information warrants the development of an educational module and/or tool for NHs to use for referrals, treatment planning, and conducting oral hygiene procedures.

The following research questions were explored: (1) is there a relationship between dental health education and NH staff perceptions regarding the implementation of oral health protocols, and (2) is there a relationship between educating NH staff on how to perform an oral assessment and identify oral conditions, and subsequent referrals for dental treatment. The goal of this research was to facilitate the implementation of oral health protocols in NHs by means that are applicable to everyday practice, utilizing an assessment tool such as the Minimum Data Set (MDS) that is routinely used for assessment data and easy to use.

Methods

Setting and Participants

This study was conducted in two NHs owned by one company in South Dakota that utilize the MDS for assessments in compliance with Medicare and Medicaid regulations for reimbursement.7 They are part of a system of health care facilities that includes hospitals, clinics, assisted-living centers, NHs, rehabilitation therapy centers, hospice care, and home care. One facility was a 112-bed skilled nursing facility in a micropolitan area, and the other facility was a 86-bed skilled nursing unit in a metropolitan area. The health system is licensed by the South Dakota State Department of Health, Medicare-certified, and accredited by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations.

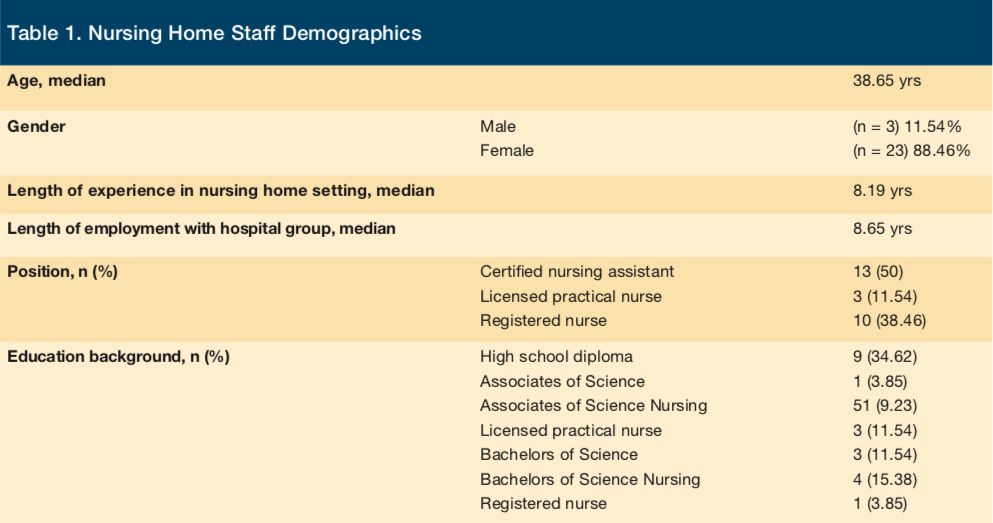

A human subject’s board approval was completed by both the health system and Eastern Washington University. A sample size of a minimum of 145 charts was needed to show a significant difference in referral rate; a total of 176 resident charts were reviewed by study completion. Charts not included in the sample were of residents who no longer resided at study site facilities or who had passed away. The NH staff (N = 26) involved in the educational module was a convenience sample of staff participating in a routine monthly continuing education staff meeting (Table 1).

Study Design

Data collection was over a six-month period: three months prior to implementation of the educational module and three months after implementation. In the initial phase, a cross-sectional comparison retrospective blind chart review was done regarding dental referrals and pre- and post-implementation Likert surveys for the NH staff.

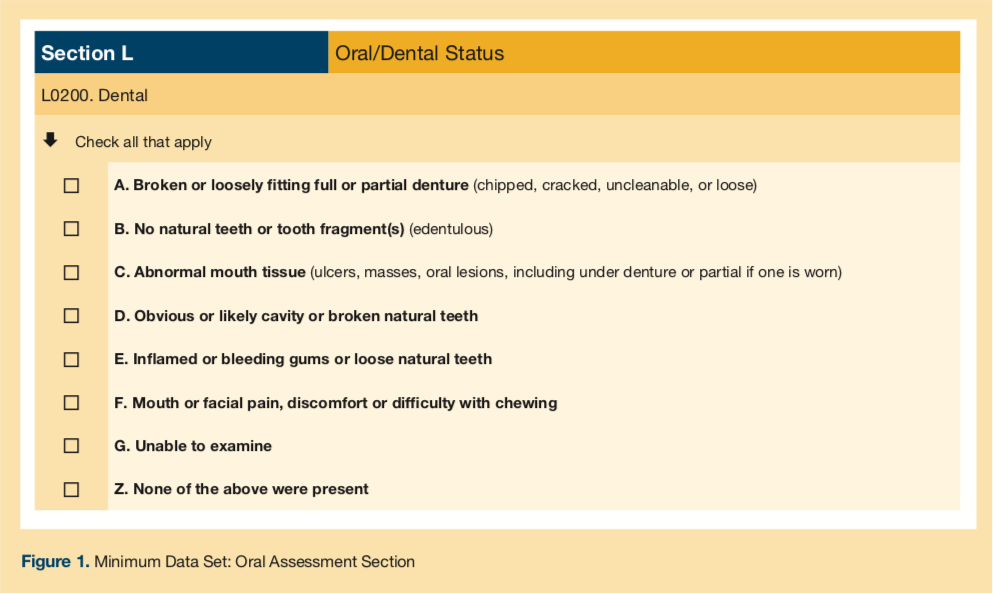

For the second phase, the principal investigator provided an oral assessment education module, which included a decision tree, to NH staff as part of the facility’s monthly continuing education meeting. The MDS provided the outline for developing the educational module and decision tree because it is a standard and mandated documentation system used in all federally funded NHs in the United States (Figure 1).

The module was a PowerPoint presentation that included tools and techniques to help NH staff provide daily oral assessments and oral care to NH residents. Since the MDS is already an assessment tool used in NHs, the oral section was chosen as an assessment tool the staff could use to perform assessments while performing daily oral hygiene procedures. Another portion of the module included pictures of common oral conditions, abnormalities, and pathologies that would be easy for NH staff to recognize. The module explained dental implications of systemic diseases, how oral health affects a person’s overall health, as well as techniques on how to complete an oral assessment of each MDS category.

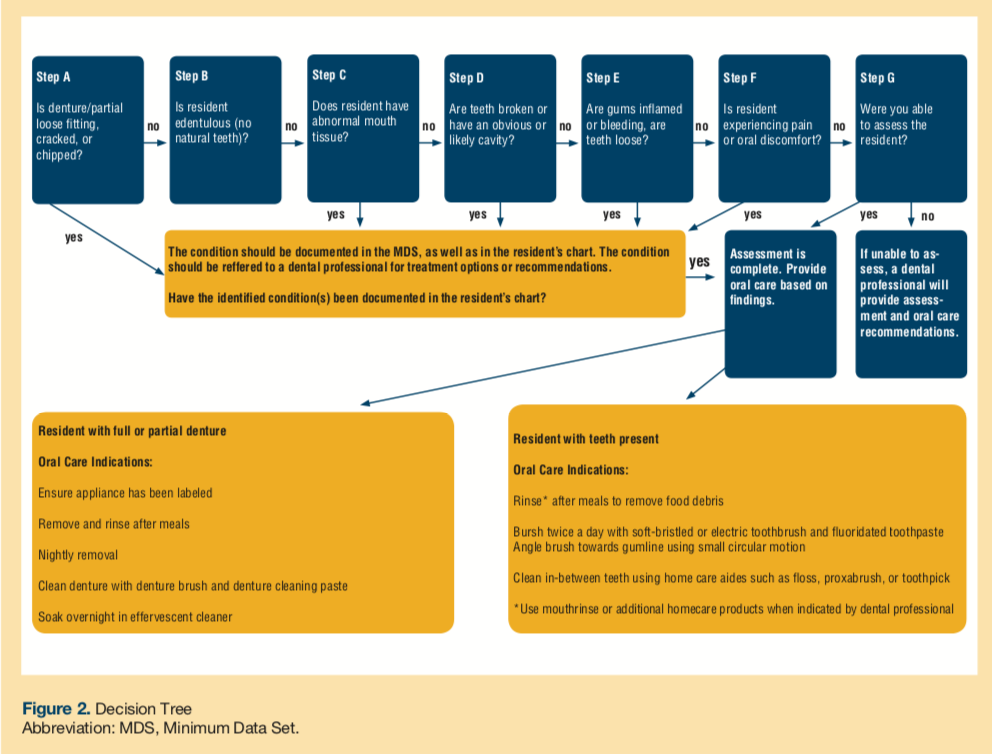

The developed decision tree, also based on the MDS, led staff through an oral assessment (Figure 2). The decision tree tool was provided in the module to help staff decide what conditions need increased attention during home care and what conditions need to be referred to professional dental treatment. The decision tree was also meant to be used by staff while performing daily oral care and assessments.

The final phase included a second retrospective chart review with data collected once a month, beginning the day of the module presentation, for a period of three months. NH staff completed surveys that provided the post-implementation survey data.

The validity for the Likert survey was tested using a Cronbach’s Alpha test and was given to 10 nurses with NH experience to measure the internal consistency of each question. The Alpha result was a .709, meaning the survey provides acceptable internal consistency for survey items. The Likert survey was then analyzed using a Wilcoxon signed rank test, and the McNemar’s test analyzed the referral data.

Results

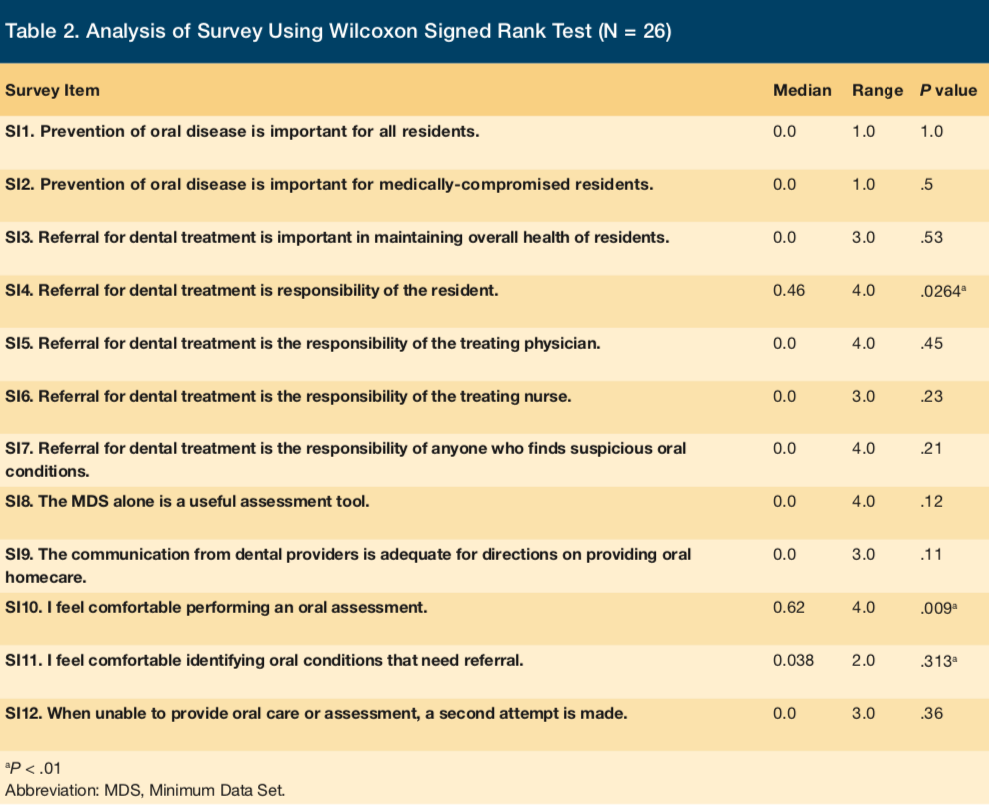

The first study objective was to investigate the relationship between educating NH staff on the dental section of the MDS and their perceptions of implementing oral health protocols. The significant difference in scores of SI4 implies a stronger agreement post-implementation to the statement “Referral for treatment is the responsibility of the resident” (P = .0264; Table 2). The significant difference in scores of SI10 indicates a stronger agreement among staff members to the statement “I feel more comfortable performing an oral assessment” post-implementation as compared to pre-implementation (P = .009). The significant difference in scores of SI11 suggests there was a stronger agreement to the statement “I feel more comfortable identifying oral conditions that need referral” among staff members post-implementation as compared to pre-implementation (P = .0313).

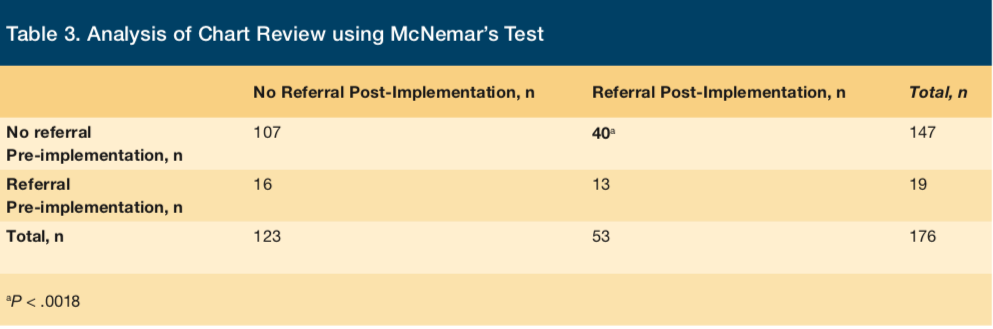

The second research objective was to investigate the relationship between educating NH staff on how to perform an oral assessment and identify oral conditions, and subsequent referrals for dental treatment. Out of 176 residents between the two NHs, 29 of the residents had been referred for dental treatment in the three months prior to implementation, resulting in a referral rate of 16%. After the implementation, 53 of those same 176 residents had been referred for dental treatment resulting in a 30% referral rate. These results strongly suggest a difference in the marginal rate of referral before module implementation and the rate of referral after implementation (P = .0018) (Table 3).

Discussion

Research repeatedly reports evidence of oral health care neglect in the growing NH population.8-12 This study provides empirical data on methods to improve the care, assessment, and referral of NH residents’ dental needs.

Research has shown that education can motivate staff to increase the frequency of oral health care being provided.12 A common assumption exists that NH staff are aware of their duties to address the oral health care needs of NH residents and are comfortable making referrals for conditions requiring professional dental treatment. This faulty assumption is the reason for this study, because if staff do not understand the value of their duties, then their ability to provide oral care and oral health assessments, consistently and confidently, diminishes. Offering NH staff access to tools such as the decision tree may lead to improved decision-making when implementing oral health protocols. Research shows that specific and directed assessment methods may result in more referrals of residents to dental providers for needed treatment.11

An increase in referral rate after the implementation of the educational module was a significant finding. Providing education on oral conditions that do or do not need referral increased the number of conditions that were actually referred. This suggests that regular education on oral health increases NH staff’s knowledge of oral conditions and, in turn, increases the amount of oral care residents receive. Education on the importance of oral health care and its relationship to overall health within the curriculum of nursing programs may also help. Providing staff with tools to support performing oral assessments and determining what dental conditions need professional attention has the potential to increase the amount of oral care residents receive.

In addition, the NH staff responses to the survey indicate that the education module and decision tree improved their perceptions of implementing oral health protocols, specifically by survey item SI10 (I feel more comfortable performing an oral assessment) (P = .009), and survey item SI11 (I feel more comfortable identifying oral conditions that need referral) (P = .0313). These responses may be related to the portion of the educational module that identified oral conditions in intraoral photographs and instruction provided on what and how to look for them. The decision tree may have also enhanced the module information and guided the NH staff on how best to proceed. The results suggest that the education provided to the NH staff made them feel more comfortable with performing dental assessments and referring dental conditions to dental professionals. Our findings corroborate existing research evidence that new assessment and evaluation techniques can increase the frequency and amount of oral care that residents receive.8,11

The stronger agreement post-implementation to the statement “Referral for treatment is the responsibility of the resident” was an unexpected finding. The continued uncertainty of the staff on referral responsibilities reflects the limited collaborative practice relationship between the medical and dental fields. An assumption can be made that staff feel residents need to be more assertive when seeking dental care. Regardless, improved communication between the two fields will increase access to dental care for residents.

More studies need to be done to determine the accuracy of the MDS assessments currently conducted by the staff in NHs. More research is also needed to further evaluate the decision tree and how it influences oral care outcomes. The decision tree was designed to guide the NH staff in making decisions on whether or not oral conditions needed a referral or an intervention. Further research may support this or similar decisions trees may be developed to improve dental care in NHs. Nonetheless, information from this study provides a basis for further studies regarding implementation of oral health protocols in NHs.

Conclusion

This study found that an education module improved the NH staff’s perceptions of implementing oral health protocols in long-term care settings, based on the increased referral rate at each site and also based on the NH staff survey responses. Oral health for older adults living in a NH continues to be an important aspect of their quality of life. A strong partnership between nursing staff and dental professionals can be instrumental in the development and implementation of interventions to meet this critical part of consistent daily care.

1. Willumsen T, Karlsen L, Naess R, Bj√∏rntvedt S. Are the barriers to good oral hygiene in nursing homes within the nurses or the patients? Gerodontology. 2012;29(2):e748-755.

2. Wårdh I, Jonsson M, Wikstram M. Attitudes to and knowledge about oral health care among nursing home personnel - an area in need of improvement. Gerodontology. 2012;29(2):787-792.

3. Forsell M, Sjögren P, Hoogstraate J, et al. Attitudes and perceptions towards oral hygiene tasks among geriatric nursing home staff. Int J Dent Hyg. 2011;9(3):199-203.

4. Miegel K, Wachtel T. Improving the oral health of older people in long-term residential care: A review of the literature. Int J Older People Nurs. 2009;4(2):97-113.

5. Finkelstein A. Oral health in the elderly; recognizing the signs of oral diseases may hasten the diagnosis and treatment of some systematic diseases and disorders. Adv for LTC Manage. 2011;14(5):46-48.

6. O'Connor LJ. Nursing standard of practice protocol: providing oral health care to older adults. ConsultGeri, a clinical website of The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing Web site. https://consultgeri.org/geriatric-topics/oral healthcare. Updated July 2012. Accessed September 2009.

7. Saliba D, Buchanan J; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Development & validation of a revised nursing home assessment tool: MDS 3.0. https://www.cms.gov. Published April 2008. Accessed September 2009.

8. Kullberg E, Sjagren P, Forsell M, Hoogstraate J, Herbst B, Johansson O. Dental hygiene education for nursing staff in a nursing home for older people. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(6):1273-1279.

9. Coleman P, Watson N. Oral care provided by certified nursing assistants in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(1):138-143.

10. de Mello A, Schaefer F, Padilha, DM. Oral health care in private and small long-term care facilities: A qualitative study. Gerodontology. 2009;26(1):53-57.

11. Munoz N, Touger-Decker R, Byham-Gray L, Maillet JO. Effect of an oral health assessment education program on nurses’ knowledge and patient care practices in skilled nursing facilities. Spec Care Dentist. 2009;29(4):179-185.

12. Sjögren P, Kullberg E, Hoogstraate J, Johansson O, Herbst B, Forsell M. Evaluation of dental hygiene education for nursing home staff. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(2):345-349.