Nonpharmacologic Management of Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia in Long-Term Care Residents

Among older long-term care residents with dementia, 80% experience behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). These can be quite distressing for residents and caregivers, and pharmacologic therapy provides little benefit and can have significant associated adverse effects. It is therefore important to be familiar with the available nonpharmacologic treatments for addressing BPSD, including cognitive/emotion-oriented interventions, behavioral management techniques, and sensory stimulation interventions. Studies of these techniques have varied widely in their methodologies and often were of limited duration. However, given the promising results reported in various studies on a variety of nonpharmacologic BPSD treatments, it is worthwhile to implement these techniques as part of an individualized treatment plan for elderly long-term care residents. Future studies are needed to more carefully evaluate the impact of nonpharmacologic BPSD treatments in a more rigorous, long-term manner.

Key words: dementia, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, nonpharmacologic treatment, long-term care

Citation: Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging. 2015;23(11):23-30.

Abstract: Among older long-term care residents with dementia, 80% experience behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). These can be quite distressing for residents and caregivers, and pharmacologic therapy provides little benefit and can have significant associated adverse effects. It is therefore important to be familiar with the available nonpharmacologic treatments for addressing BPSD, including cognitive/emotion-oriented interventions, behavioral management techniques, and sensory stimulation interventions. Studies of these techniques have varied widely in their methodologies and often were of limited duration. However, given the promising results reported in various studies on a variety of nonpharmacologic BPSD treatments, it is worthwhile to implement these techniques as part of an individualized treatment plan for elderly long-term care residents. Future studies are needed to more carefully evaluate the impact of nonpharmacologic BPSD treatments in a more rigorous, long-term manner.

Key words: dementia, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, nonpharmacologic treatment, long-term care

Citation: Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging. 2015;23(11): 23-29.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Dementia is characterized by chronic, progressive cognitive impairment that affects one’s ability to perform everyday activities. According to the World Health Organization, 47.5 million people worldwide have dementia, and the total number of individuals with dementia is projected to reach 75.6 million in 2030 and 135.5 million in 2050.1 Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) are very common as the disease progresses, impacting 60% of community dwelling patients and 80% of long-term care (LTC) facility residents.2-4

Although BPSD are common, it is often difficult to clearly define these behaviors and to determine safe, effective treatment options due to variable presentations, the occurrence of multiple behaviors within an individual patient, and the presence of associated medical co-morbidities. In fact, BPSD can be even more challenging to manage than the characteristic cognitive decline associated with dementia. They often lead to increased caregiver burden, early nursing home placement, hospitalizations, and excess morbidity and mortality.5-7 LTC staff are critical to the recognition and successful management of dementia-associated behaviors in this population. In this review, we describe the behaviors and features of BPSD, the process of evaluating LTC residents with these symptoms, and the many available nonpharmacologic treatment options for BPSD in this population.

Description of BPSD

BPSD can be divided into psychotic features and nonpsychotic behaviors. Psychotic features of dementia include hallucinations, delusions, and delusional misidentification syndromes. Hallucinations are wakeful sensory experiences of content that is not actually present. Although these experiences can affect any of the five senses, auditory and visual hallucinations are the most common among patients with dementia. Delusions are strongly held false beliefs that are not typical of a person’s religious or cultural beliefs. Confusion and memory loss often contribute to these beliefs in individuals with dementia. Patients with delusional misidentification syndromes consistently misidentify persons, places, objects, or events. The prevalence of these syndromes varies with different etiologies of dementia. In their 2008 study, Harciarek and Kertesz8 identified misidentification syndromes in 15.8% of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, 16.6% of patients with Lewy body dementia, and 8.3% of patients with semantic dementia.

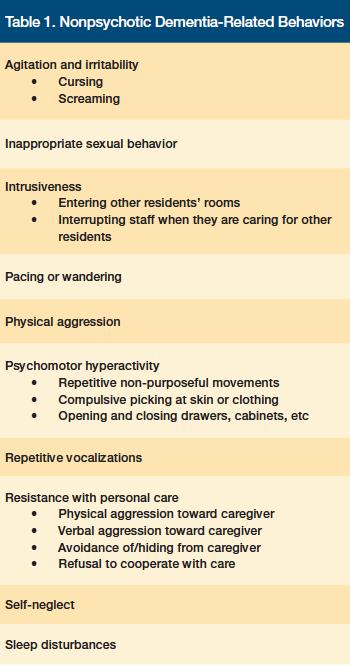

Nonpsychotic behaviors affect up to 98% of patients with dementia at some point in the disease course.9 These behaviors include physical aggression, agitation/irritability, sleep disturbances, and self-neglect (Table 1).10

When formulating a treatment plan for BPSD, it is crucial to begin by accurately describing the specific behavior(s). The importance of this first step is highlighted in the following DICE approach to managing behavioral symptoms in patients with dementia: (1) Describe; (2) Investigate; (3) Create; and (4) Evaluate.9,11 During the first step of this approach, LTC staff describe the behavior and the context in which it occurs in as much detail as possible. It is helpful to query the patient regarding the episode and to see if he or she can provide further information about factors that contributed to the behavior, although this is usually not possible in cases of advanced dementia. Based on their long-standing relationship with the elderly individual, family members can also be a valuable source of information in understanding what may have prompted certain behaviors.

Evaluating BPSD

Once BPSD are characterized, LTC staff should investigate for possible underlying and modifiable causes per the second step of the DICE approach.9,11 Possible contributing factors can be categorized into patient, caregiver, environmental, and cultural considerations. Patient-related factors that may contribute to new or worsening behavioral symptoms include medication changes, unrecognized infection (eg, urinary tract infection), undertreated pain, sleep issues, sensory deprivation (ie, poor vision, decreased hearing), worsening cognitive function, and psychiatric comorbidities. In addition to evaluating current patient-related factors, LTC staff should investigate the patient’s past issues with violence, substance abuse, or personality issues, as these may contribute to his or her current behaviors and inform management decisions. Facility caregiver considerations include lack of understanding of the disease, personal health issues, substance abuse, burnout, and lack of appropriate communication skills to optimally interact with the individual with dementia. Environmental factors can play an important role in BPSD and include difficulty adjusting to a new environment, lack of activities to bring pleasure or relieve boredom, and over- or understimulation.

Pharmacologic Treatment of BPSD

Effective BPSD management is often challenging and requires frequent symptom reassessments and treatment adjustments as the disease progresses. Currently, no pharmacologic therapies are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of dementia-related behaviors. The use of antipsychotic medications for this indication is common, however, despite findings that they provide modest, if any, benefit compared with placebo in the treatment of behavioral symptoms.12-14 At the end of 2013, the prevalence of antipsychotic use in US LTC facilities was 20.2% despite ongoing work by the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to reduce the usage of these medications.15 This is especially concerning given the black box warning of increased mortality among elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis and associated risk of cerebrovascular and cardiac events.16,17 Further, antipsychotics are associated with other side effects, including sedation, falls, extrapyramidal symptoms, and metabolic effects.18

Although nonpharmacologic therapies are the preferred choice of treatment for BPSD, medications can be a useful adjuvant in certain situations, including during times of transition (eg, when new behavioral techniques are introduced, the adjustment period following a move to a LTC facility) or when behaviors are exacerbated by other comorbid conditions. For instance, underlying conditions (eg, pain, depression) often intensify BPSD and should be treated with appropriate pharmacologic interventions. Further, patients often experience increased anxiety and depression when faced with a life change. In these situations, it is reasonable to treat the individual with an antidepressant or anxiolytic in addition to behavioral techniques. A clear understanding and appropriate use of nonpharmacologic management techniques for dementia-associated behaviors, with the use of selected medications during times of transition or to treat comorbid conditions, is crucial in further reducing antipsychotic medication usage and associated adverse outcomes among LTC residents.

Nonpharmacologic Treatment for BPSD

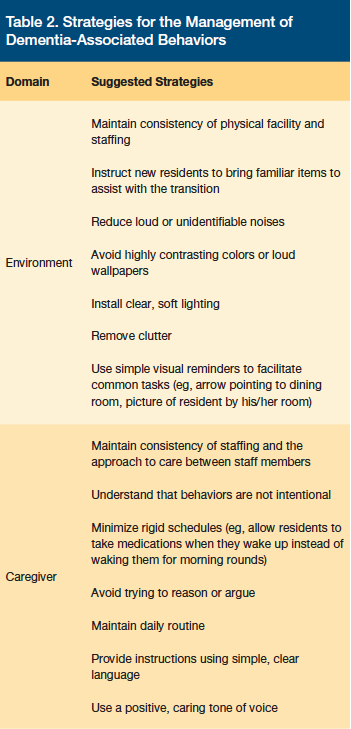

The development of a nonpharmacologic behavioral treatment approach is among the tasks listed in step 3 (Create) of the DICE approach to managing BPSD.9,11 Facility caregivers, family members, and the resident with dementia (when possible) should work together to develop an individualized therapy plan. Behavioral and environmental strategies can be characterized as generalized or targeted. Generalized strategies focus on improving the environment and caregiver skills rather than on specific behaviors or residents (Table 2).9,11 Targeted strategies address an individual resident’s specific behaviors and are often essential in reducing dementia-related behaviors. Following the implementation of a nonpharmacologic treatment strategy, the outcome’s safety and efficacy should be evaluated per step 4 of the DICE approach.9,11 While further study regarding the efficacy and practicality of individualizing nonpharmacologic behavioral management techniques in LTC is warranted, targeted strategies that may be considered include cognitive/emotion-oriented interventions, behavioral management techniques, and sensory stimulation interventions.11

Cognitive/Emotion-Oriented Interventions

Cognitive/emotion-oriented interventions include cognitive stimulation therapy, reminiscence therapy, simulated presence therapy (SPT), validation therapy, and behavioral management techniques.

Cognitive stimulation therapy. Cognitive and multisensory stimulation consists of a range of activities that provide stimulation for thinking, memory, and concentration in elderly patients with dementia.19,20 Techniques such as games, word associations, music, dancing, singing, art, gardening, and food preparation are used to stimulate individuals in a pleasant manner, usually in a small group setting. The therapies can be individualized to fit the resident’s cognitive abilities, but are usually the most effective in older patients with mild to moderate—as opposed to severe—dementia. In addition, it is beneficial to engage family members to help understand a resident’s prior interests so that cognitive stimulation activities can be individualized based on his or her tastes. Cognitive stimulation therapy can be led by LTC staff, activity therapists, or even family members or volunteers. There is conflicting evidence regarding the impact of cognitive stimulation therapy on BPSD, but some studies have found it to be beneficial in elderly individuals with dementia-related behaviors, including anxiety and depression.21-23 There is also evidence suggesting that it may be beneficial in improving memory, thinking, communication abilities, and quality of life.19

Reminiscence therapy. Reminiscence therapy is an ordered process of reflection on significant life events.24 Memory aids, including pictures, objects, music, video clips, movies, and periodicals (eg, newspapers, magazines, catalogs), can be used to trigger one’s memories. Reminiscence therapy can be useful in improving communication, retaining identity and self-worth,25 and reducing symptoms of depression among elderly patients with dementia.26 It can also help staff members to better understand a resident’s past life experiences, which can lead to a closer relationship, and can allow family members to enjoy being involved in the care of their loved one as they recall positive life events together. As dementia progresses, individuals often respond better to one-on-one reminiscence therapy that focuses more on the emotions associated with past events than on attempting to recall specific memories. Reminiscence therapy is typically led by activity therapists and long-term care staff, although techniques can be taught to motivated family members and volunteers. Despite the possible benefits of reminiscence therapy, some elders with dementia may experience a negative or agitated reaction to a life review. Individuals should never be encouraged or forced to recall past events if they are reluctant to do so or find the activity upsetting.

Simulated presence therapy. SPT involves the use of personalized conversations on video or audiotape. For this therapy, family members tape their portion of a conversation about pleasant memories, leaving pauses in the recording to give the individual with dementia a chance to respond. This therapy modality can reduce disruptive, agitated, and depressed behaviors in some individuals with dementia.27 In addition to recording descriptions of pleasing memories from the past, staff members can engage family members in recording conversations that are applicable to certain situations or behaviors. For example, if a patient exhibits signs of being sad or lonely at bedtime, he or she may respond well to a recording of a family member wishing him or her a good night and/or leading him or her in a familiar prayer. Participating in SPT can be a positive experience for family members, as it allows them to contribute to their loved one’s well-being.28 SPT should be carefully selected and closely monitored, however, as it can increase agitation in some elders.27

Validation therapy. Validation therapy is based on the notion that the feelings and memories of the individual with dementia should be respected and validated, even if they are inconsistent with reality.29,30 It recognizes that there is a reason behind the behavior of elders with disorientation. Validation theory postulates that these individuals may be working through unresolved tasks from the past (resolution) or seeing with their “mind’s eye.” Using this perspective, this type of therapy focuses on understanding the meaning behind behaviors and respecting the individual’s perception of reality. Various techniques, including rephrasing and active listening, can be used to link the challenging behavior with the feeling that it represents.31 For example, when an individual with dementia is asking or looking for a deceased loved one, staff should say, “You sound as if you miss them very much and want to see them,” or “Tell me about them. What made them so special?” rather than reminding him or her that this person is deceased. Validation therapy techniques are typically used by long-term care staff, although they can also be taught to motivated family members and volunteers. Results of studies examining the efficacy of validation therapy in reducing BPSD are mixed.32

Behavioral Management Techniques

Behavioral management techniques that can be used in individuals with dementia are quite varied and include positive reinforcement or token economies, habit training, functional analysis, and communication training. In general, these techniques have been shown to be valuable for the treatment of BPSD, although the specific technique used and outcome measures vary widely in the studies.33 The antecedent-behavior-consequence analysis of applied behavior analysis can be used as a basis for many behavioral management techniques, including positive reinforcement, token economies, and habit training.34 Using this model, the antecedent or event that triggered the behavior is analyzed. This antecedent can then be modified to reduce or prevent the resultant behavior (eg, move the location of where an easily overstimulated resident eats from a noisy, community dining room to a more private area) or a positive consequence can be employed to promote ongoing desired behaviors. For example, if a resident is resistant to bathing but allows his or her face to be washed without difficulty, he or she would immediately be given a pleasurable small reward (eg, food, drink, listening to a special song). The personal care is then expanded to include washing his or her face and chest followed by the reward, with the process repeating and including more body parts each time until full bathing can achieved with minimal undesirable behaviors. It is much more effective and pleasurable—for both staff and patients—to use positive reinforcement than to institute negative reinforcement for undesirable behaviors.

Sensory Stimulation Interventions

Sensory stimulation interventions include music therapy, aromatherapy, massage, and Snoezelen multisensory stimulation therapy, all of which will be discussed herein.

Music therapy. Individuals with dementia often retain the ability to sing familiar songs and play musical instruments late into the course of their disease.35-37 Research has shown that music therapy can be effective in treating BPSD, enhancing communication, and increasing cognitive functions, such as speech and attention.38-40 There are many different music therapy modalities described in the literature, including active music therapy based on music therapy models (led by a music therapist), music-based interventions such as singing or moving to music (do not require a music therapist), caregivers singing, individualized listening to music, and background music. Experts recommend the implementation of a global music approach to persons with dementia at the time of LTC facility admission.41 This would entail an initial evaluation by a music therapist and a physician to determine the needs and abilities of the resident with dementia. An individualized plan would then be developed to implement the various music therapy modalities in a way that is most beneficial to the resident. This plan would have to be revisited and modified as the dementia progressed.

If the services of a music therapist are not available, music therapy can still be implemented by LTC staff, including the activity therapist. A very helpful first step in implementing a music therapy program for an individual is asking the elderly resident’s family or friends about what types of music he or she has most enjoyed over his or her lifetime. Elders are often engaged by music that was popular when they were between 18 and 25 years of age. As the dementia progresses, individuals may respond most positively to music from their childhood.42 Once the music is chosen, it can be loaded onto a personal listening device or tablet. Staff can assist the elder with selecting the music based on the mood or behavior they are trying to impact (eg, simulative music has a quicker tempo and percussive beat to encourage movement or appetite, sedative music such as ballads or lullabies has a slower tempo to help reduce agitation or assist with sleep). In addition to listening, singing, moving, and conducting activities to music, many elderly individuals enjoy making music, especially if they used to play an instrument.

Aromatherapy. Aromatherapy, most commonly using essential oils, can be administered through application to the skin, inhalation through the respiratory system, or the ingestion of certain foods or teas. Essential oils are extracted from the flowers, barks, stem, leaves, roots, fruits, and other parts of the plant.43 Aromatherapy has been used to reduce unwanted behavioral symptoms, improve sleep, and increase motivation in individuals with dementia. Essential oils that are often recommended for individuals with dementia include lavender, peppermint, ginger, rosemary, bergamot, and lemon balm. Lavender may be especially helpful with improving sleep and can be sprayed onto bed linens or used as massage oil.44,45 Peppermint can be energizing, so it is best used in the morning. Peppermint oil can be diffused into the room, used as massage oil, or placed into a bath in order to relieve anxiety.46 Ginger oil is often used for gastrointestinal issues and to improve appetite.47 It can be inhaled or ginger root can be steeped as a tea. Despite the proposed benefits of certain essential oils and aromatherapy, studies have been equivocal, and more controlled, larger-scale studies are needed to determine whether aromatherapy has positive effects on BPSD.48,49

Individuals with dementia may also have a positive response to perfumes that they have found pleasant in the past. Further, the aroma of certain foods can have very positive memory associations for some people. Methods of incorporating this could include baking cookies or bread, offering a favorite scented tea, or encouraging elders to pause before eating to enjoy the aroma of fresh fruit.

Massage. Massage is frequently used to reduce anxiety, aggression, and depression in elders with dementia. A 2013 literature review by Moyle et al50 revealed significant variation among studies evaluating the impact of massage on BPSD, with only one study deemed to be of adequate quality to include in the review. This 2009 study by Holliday-Welsh and colleagues51 found a significant reduction in agitation among LTC residents treated with massage. Authors of a more recent study from 2014 reported a nonsignificant reduction in heart rate and blood pressure among LTC residents with dementia who received foot massages.52

When implementing massage therapy for an elder with dementia, LTC staff should start with a short, focused session to determine whether the therapy has a positive response or if it is overstimulating. Types of massage that are often well received by elders with dementia and can be provided by nursing home staff include hand massage, slow-stroke back massage, and foot massage. Sessions as brief as three to five minutes may provide benefit.53 Massage can be performed using pleasantly scented lotions or oils to enrich the experience. Given the ease of implementation, ability to be performed by trained or lay caregivers, and possible positive impact on both the resident and the masseuse, further large-scale studies evaluating the impact of massage on BPSD are warranted.

Snoezelen multisensory stimulation therapy. Snoezelen multisensory stimulation therapy, developed in the Netherlands, is based on the idea that individuals may experience neuropsychiatric symptoms due to periods of sensory deprivation.54 This therapy involves the use of a variety of stimuli, including images, lights, tactile objects, music, and aromatherapy, to stimulate and relax the person with dementia without set expectations regarding his or her reaction. The treatment normally occurs in a dedicated room. Ideally, the outfitting of the room should be a collaborative effort between staff and involved family members who are familiar with the resident’s current cognitive state and past preferences regarding art, music, and smell, among other things. Possible items to include in the room are an assortment of objects from nature that can be updated on a seasonal basis; blocks, beads, or other small items that are pleasing to the touch and can be connected to build larger objects; soft blankets or plush animals; pleasant-smelling lotions; and simple art supplies, such as colored pencils and paper. If facilities do not have the space or resources to develop a Snoezelen room, sensory baskets or carts are a practical, portable alternative. Studies of Snoezelen therapy have demonstrated enjoyment by individuals with dementia and some improvement in disruptive and apathetic behavior during the therapy.33 Additional studies are needed, however, to evaluate the long-term impact of this therapy and to examine whether there are any benefits beyond those observed with other stimulating experiences, such as being outside.55

Future Directions

There are multiple, important benefits of using nonpharmacologic treatment approaches for BPSD, including improved quality of life and reduced antipsychotic medication use. However, several challenges remain that must be addressed in the future to optimize the nonpharmacologic care for elderly LTC residents with dementia. First, many of the previous studies that have evaluated nonpharmacologic treatment approaches were brief in duration and employed variable methodologies, promoting a single behavioral intervention instead of a personalized, comprehensive treatment plan. They also used assessment tools that do not adequately capture behavioral outcomes. Longer-term studies of rigorous design that assess a comprehensive behavioral management program would allow the true impact of nonpharmacologic interventions to be better understood.

In addition, while BPSD are common during the course of Alzheimer’s disease, symptoms vary significantly over time within and between individuals. This makes careful, longitudinal analysis of BPSD within a stable population difficult, unless the study includes a well-matched and/or randomized control group. Further, the successful implementation of nonpharmacologic BPSD management techniques into LTC is challenging. Many of these interventions are labor-intensive and require specialized training, leading to challenging implementation in busy clinical settings. Options for addressing this include selecting dementia advocates to receive additional training and forming an interdisciplinary dementia team. Finally, it can be challenging to treat some of the BPSD for which nonpharmacologic interventions are ineffective, such as hallucinations. In this case, education of long-term care staff and family members regarding lack of treatment efficacy, and reassurance of family members as they support the elder throughout the disease process, are warranted.

Conclusion

BPSD, including psychotic features and nonpsychotic behaviors, are extremely common among elders in LTC. Successful management includes accurately describing the symptoms and trying to ascertain whether there are modifiable triggers contributing to the behaviors. The risks associated with pharmacologic treatment, particularly using antipsychotics, are well recognized and nonpharmacologic management should be employed instead of or in addition to pharmacologic treatment whenever possible. Cognitive/emotion-oriented interventions (eg, cognitive stimulation therapy, reminiscence therapy, SPT, validation therapy), behavioral management techniques (eg, positive reinforcement or token economies, habit training, functional analysis, communication training), and sensory stimulation interventions (eg, music therapy, aromatherapy, massage, Snoezelen multisensory stimulation therapy) are some nonpharmacologic options for addressing BPSD. Further study is needed to clarify which management techniques are most effective and how to successfully integrate them into the LTC environment. u

References

1. Media Centre: Dementia Fact Sheet. World Health Organization Website. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs362/en/. Updated March 2015; accessed October 1, 2015.

2. Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, et al. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288(12):1475-83.

3. Lyketsos CG, Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, et al. Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: findings from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):708-14.

4. Zuidema SU, Derksen E, Verhey FR, Koopmans RT. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in a large sample of Dutch nursing home patients with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(7):632-8.

5. Kales HC, Chen P, Blow FC, Welsh DE, Mellow AM. Rates of clinical depression diagnosis, functional impairment, and nursing home placement in coexisting dementia and depression. AmJ Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(6):441-449.

6. Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2090-2097.

7. Wancata J, Windhaber J, Krautgartner M, Alexandrowicz R. The consequences of non-cognitive symptoms of dementia in medical hospital departments. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2003;33(3):257-271.

8. Harciarek M, Kertesz A. The prevalence of misidentification syndromes in neurodegenerative diseases. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(2):163-169.

9. Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG, Detroit Expert Panel on Assessment and Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia. Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in clinical settings: recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panel. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(4):762-769.

10. Lyketsos CG, Carrillo MC, Ryan JM, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(5):532-539.

11. Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ. 2015;350:h369.

12. Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294(15):1934-1943.

13. Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1525-1538.

14. Ballard C, Hanney ML, Theodoulou M, et al. The dementia antipsychotic withdrawal trial (DART-AD): long-term follow-up of a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(2):151-157.

15. National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care exceeds goal to reduce use of antipsychotic medications in nursing homes: CMS announces new goal. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Website. www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-releases/2014-Press-releases-items/2014-09-19.html. Published September 19, 2014; accessed October 1, 2015.

16. Public Health Advisory: Deaths with Antipsychotics in Elderly Patients with Behavioral Disturbances. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Website. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm053171.htm. Published April 11, 2005; accessed October 1, 2015.

17. Information for Healthcare Professionals: Conventional Antipsychotics. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Website. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm124830.htm. Published June 16, 2008; accessed October 1, 2015.

18. Gareri P, De Fazio P, Manfredi VG, De Sarro G. Use and safety of antipsychotics in behavioral disorders in elderly people with dementia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34(1):109-123.

19. Woods B, Aguirre E, Spector AE, Orrell M. Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Systm Rev. 2012;2:CD005562.

20. De Oliviera TCG, Soares FC, De Macedo ED, et al. Beneficial effects of multisensory and cognitive stimulation on age-related cognitive decline in long-term-care institutions. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:309-321.

21. Stanley MA, Calleo J, Bush AL, et al. The peaceful mind program: a pilot test of a cognitive-behavioral-therapy-based intervention for anxious patients with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(7):696-708.

22. Gitlin LN, Winter L, Burke J, Chernett N, Dennis MP, Hauck WW. Tailored activities to manage neuropsychiatric behaviors in persons with dementia and reduce caregiver burden: a randomized pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(3):229-239.

23. Kiosses DN, Arean PA, Teri L, Alexopoulos GS. Home-delivered problem adaptation therapy (PATH) for depressed, cognitively impaired, disabled elders: A preliminary study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(11):988-998.

24. Butler RN. The life review: an interpretation of reminiscence in the aged. Psychiatry. 1963;26:65-76.

25. Dempsey L, Murphy K, Cooney A, et al. Reminiscence in dementia: A concept analysis. Dementia. 2014;13(2):176-192.

26. Woods B, Spector A, Jones C, Orrell M, Davies S. Reminiscence therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD001120.

27. Zetteler J. Effectiveness of simulated presence therapy for individuals with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12(6):779-785.

28. Remington R, Futrell M. Addressing Problem Behaviors Common To Late-Life Dementias. In: KD Melillo, SC Houde, eds. Geropsychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC;2011: 313-335.

29. Feil N, Altman R. Letter to the editor: Validation theory and the myth of the therapeutic lie. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2004;19(2):77-78. https://aja.sagepub.com/content/19/2/77.extract#. Accessed October 1, 2015.

30. Feil N. Validation therapy. Geriatr Nurs. 1992;13(3):129-133.

31. Neal M, Barton Wright P. Validation therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(3):CD001394.

32. O’Connor DW, Ames D, Gardner B, King M. Psychosocial treatments of psychological symptoms in dementia: a systematic review of reports meeting quality standards. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(2):241-251.

33. O’Neil ME, Freeman M, Christensen V, Telerant R, Addleman A, Kansagara D. A Systematic Evidence Review of Non-pharmacological Interventions for Behavioral Symptoms of Dementia. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs; March 2011.

34. Noguchi D, Kawano Y, Yamanaka K. Care staff training in residential homes for managing behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia based on differential reinforcement procedures of applied behaviour analysis: a process research. Psychogeriatrics. 2013;13(2):108-117.

35. Cowles A, Beatty WW, Nixon SJ, et al. Musical skill in dementia: a violinist presumed to have Alzheimer’s disease learns to play a new song. Neurocase. 2003;9(6):493-503.

36. Cuddly LL, Duffin J. Music, memory, and Alzheimer’s disease: is music recognition spared in dementia, and how can it be assessed? Med Hypotheses. 2005;64(2):229-235.

37. Fornazzari L, Castle T, Nadkarni S, et al. Preservation of episodic musical memory in a pianist with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;66(4):610-611.

38. Raglio A, Bellelli G, Traficante D, et al. Efficacy of music therapy in the treatment of behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(2):158-162.

39. Ueda T, Suzukamo Y, Sato M, Izumi S. Effects of music therapy on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(2):628-641.

40. Van de Winckel A, Feys H, De Weerdt W, Dom R. Cognitive and behavioural effects of music-based exercises in patients with dementia. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18(3):253-260.

41. Raglio A, Filippi S, Bellandi D, Stramba-Badiale M. Global music approach to persons with dementia: evidence and practice. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1669-1676.

42. Clair AA. Education and Care: Music. Alzheimer’s Foundation of America website.. https://www.alzfdn.org/EducationandCare/musictherapy.html. Accessed November 5, 2015.

43. Ali B, Al-Wabel NA, Shams S, Ahamad A, Khan SA, Anwar F. Essential oils used in aromatherapy: a systemic review. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2015;5(8):601-611.

44. Holmes C, Hopkins V, Hensford C. Lavender oil as a treatment for agitated behavior in severe dementia: a placebo controlled study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(4):305-8.

45. Fujii M, Hatakeyama R, Fukuoka Y, et al. Lavender aroma therapy for behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia patients. Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 2008;8(2):136-138.

46. Stea S, Beraudi A, De Pasquale D. Essential oils for complementary treatment of surgical patients: state of the art. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014.

47. Lua PL and Zakaria NS. A brief review of current scientific evidence involving aromatherapy use for nausea and vomiting. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18(6):534-40.

48. Forrester LT, Maayan N, Orrell M, Spector AE, Buchan LD, Soares-Weiser K. Aromatherapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD003150.

49. Fu CY, Moyle W, Cooke M. A randomised controlled trial of the use of aromatherapy and hand massage to reduce disruptive behaviour in people with dementia. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:165.

50. Moyle W, Murfield JE, O’Dwyer S, Van Wyk S. The effect of massage on agitated behaviours in older people with dementia: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(5-6):601-610.

51. Holliday-Welsh DM, Gessert CE, Renier CM. Massage in the management of agitation in nursing home residents with cognitive impairment. Geriatr Nurs. 2009;30(2):108-117.

52. Moyle W, Cooke ML, Beattie E, et al. Foot massage and physiological stress in people with dementia: a randomized controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20(4):305-311. Published ahead of print September 18, 2013.

53. Harris M, Richards KC, Grando VT. The effects of slow-stroke back massage on minutes of nighttime sleep in persons with dementia and sleep disturbances in the nursing home: a pilot study. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30(4):255-63.

54. Chung JC, Lai CK, Chung PM, French HP. Snoezelen for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(4):CD003152.

55. Anderson K, Bird M, Macpherson S, McDonough V, Davis T. Findings from a pilot investigation of the effectiveness of a snoezelen room in residential care: should we be engaging with our residents more? Geriatr Nurs. 2011;32(3):166-177.