A Multifaceted, Evidence-Based Program to Reduce Inappropriate Antibiotic Treatment of Suspected Urinary Tract Infections

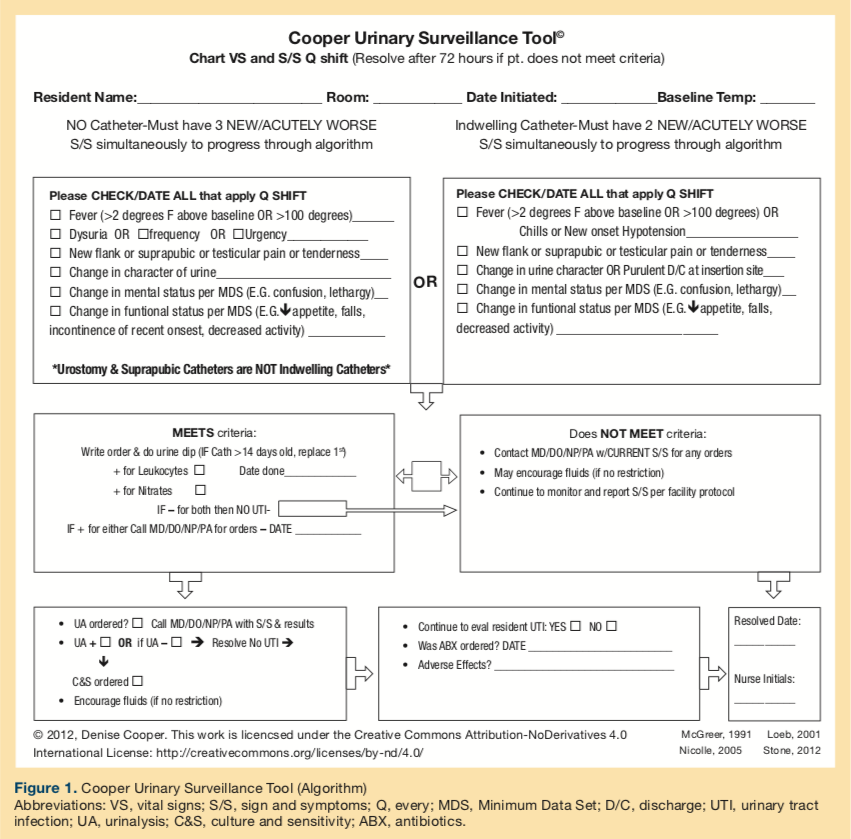

Asymptomatic bacteriuria, common in long-term care (LTC) residents, can appear similar to urinary tract infections (UTIs) based on urinalysis (UA) alone but can be differentiated from UTI if the resident has either no symptoms or insufficient symptoms to diagnose UTI. Asymptomatic bacteriuria unlike UTI, should not be treated with antibiotics. Therefore, appropriate assessment of signs and symptoms in residents with suspected UTI could reduce misdiagnoses of UTI and inappropriate antibiotic use. The purpose of this quality improvement project was to implement a multifaceted, evidence-based program to improve knowledge and assessment of UTI signs and symptoms in LTC residents. The project included a newly developed algorithm, the Cooper Urinary Surveillance Tool, to be used by nurses and providers along with staff education and change champions. Pre- and post-analysis measured UTI incidence, UA testing frequency, appropriateness of UTI diagnoses, and provider knowledge. Results showed statistically significant reductions in the incidence of overall UTI diagnoses and in inappropriate UTI diagnoses. The findings demonstrate that the intervention was effective for improving the appropriateness of UTI diagnoses in order to reduce unnecessary prescribing of antibiotics to LTC residents.

Key words: antibiotic resistance, long-term care, urinary tract infections, asymptomatic bacteriuria

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has named antibiotic resistance as one of the world’s most pressing health threats and subsequently created a toolkit for antibiotic stewardship.1 Compared with communities, long-term care facilities (LTCFs) have much higher incidences of antibiotic-resistant organisms2 that require treatment with alternative and expensive antibiotics, significantly limiting the number of effective antibiotics and increasing the risk of opportunistic infections like Clostridium difficile (C diff).1,2 A common scenario in which antibiotics are overused in LTCFs is for the treatment of residents with suspected urinary tract infections (UTIs). Currently, UTIs are estimated to comprise about one-third of reported infections treated with antibiotics in LTC residents.3-5 Universally, UTI is defined as bacteria in the urine, identified using a urinalysis test (UA), along with specified clinical signs and symptoms (S/S) such as fever, dysuria, suprapubic pain or tenderness, change in urine character, and/or worsening mental or functional status.6-9 In contrast, asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) describes when a patient has laboratory-identified bacteria in the urine but either no S/S or an insufficient number of S/S. 2,6,7 ASB can be healthcare-acquired in LTC residents.1 The rate of ASB among LTC residents is estimated to be 25% to 50% for women and 15% to 40% for men. For catheterized patients, this rate goes up to almost 100%.6 Although common, ASB without the presence of sufficient S/S that are associated with UTI does not require treatment.1 The results of several studies comparing residents treated with antibiotics for ASB to those not treated found no benefit to screening for or treating ASB.2,6,10 Indeed, one study found that LTC residents with ASB who were treated with antibiotics were 8.5 times more likely to develop C diff than residents who were not treated with antibiotics.4 Due to the adverse effects of antibiotic use, patient morbidity is increased with ASB treatment, but no increases in mortality rates or hospitalizations were found for withholding antibiotic treatment.1,6,10-15 Overall, the literature supports treating symptomatic UTIs in LTC residents with antibiotics6-9,16 while strongly and unanimously rejecting treating ASB.2,4,6,10

Because UTI and ASB are indistinguishable on UA results alone, diagnosing UTI using UA tests without assessing whether sufficient clinical S/S for a UTI diagnosis are present can lead to misdiagnosis, resulting in inappropriate antibiotic treatment.6-10,17,18 In one study, approximately 50% of noncatheterized and 80% of catheterized LTC residents treated with antibiotics for a UTI had no documented S/S.19 Similarly, in another study, 85% of residents treated with antibiotics for UTI actually had ASB, and therefore were inappropriately treated.4 Unnecessary UA tests and overtreatment with antibiotics can increase adverse effects, antibiotic resistance, and health care costs. Appropriate S/S assessment could make the incidence much less frequent.3-5

The purpose of this quality improvement project was to address the insufficient assessment of LTC residents with suspected UTI by implementing an evidence-based, multifaceted program. The project’s overall objective was to reduce inaccurate UTI diagnoses and inappropriate antibiotic treatment by improving clinicians’ knowledge of ASB and assessment of UTI S/S.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

The project was IRB-reviewed at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor and considered exempt. The administrator approved the project to be implemented at Durand Senior Care, a 151-bed, for-profit LTC and rehabilitation facility located in southeast Michigan. Frontline nurses at the facility were asked to identify clinical issues and reported being concerned about UTI treatment and recurrence rates. Facility administrators, directors, and nursing managers all agreed that UTI prevalence, recurrence, and inappropriate antibiotic treatment were serious issues that must be addressed. This information was obtained informally by talking to nurses using the Titler Model, which can either formally or informally ask frontline nurses about current patient care issues for quality improvement.

The Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice to Promote Quality Care was used as this project’s framework.20,21 Using a bottoms-up approach, the model actively engages, involves, and challenges frontline staff nurses to appraise and alter their practices using reliable evidence.20,22

Three strategies were used for this project: (1) a newly created algorithm, the Cooper Urinary Surveillance Tool; (2) didactic education for nurses, nurse practitioners, physicians, and physician assistants; and (3) the role of change champions. Research shows that didactic instruction alone is less effective than multifaceted educational strategies,22 which have been shown to improve adherence.11,15 Nurses and providers all received the same education, which included how to use the algorithm and the knowledge test. Nurses were instructed to use the algorithm independently, but providers supported its use and communicated with nurses about where patients were on the algorithm if they were being monitored.

Cooper Urinary Surveillance Tool

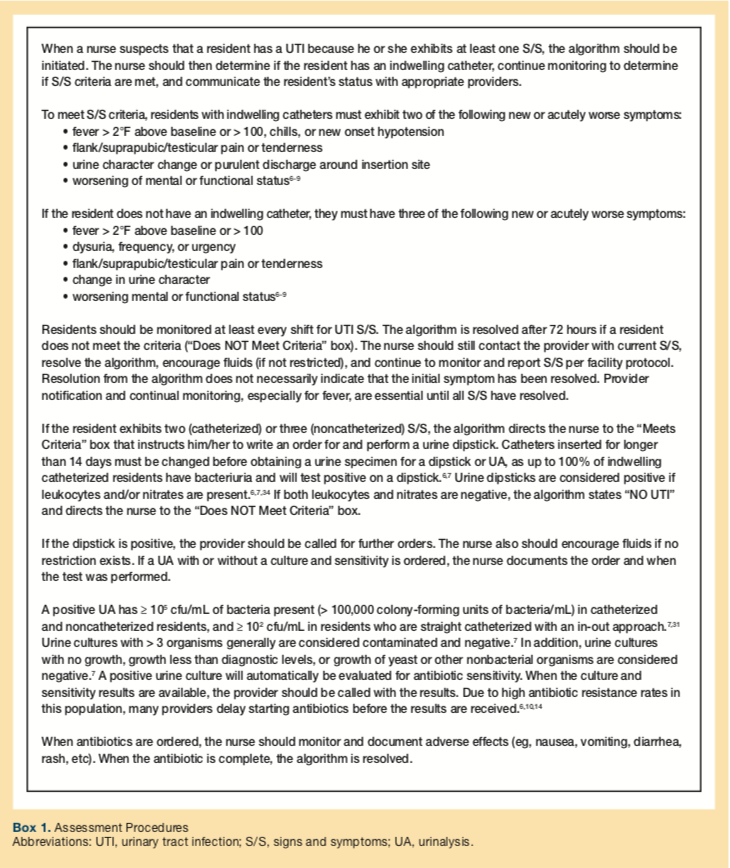

For this project, we created an evidence-based algorithm to guide nurses in their assessment of UTI S/S, which we called the Cooper Urinary Surveillance Tool (Figure 1). An algorithm was included because this strategy has been shown to improve diffusion of practice guidelines.11,13,15 While other similar tools have been created, none has been widely adopted.

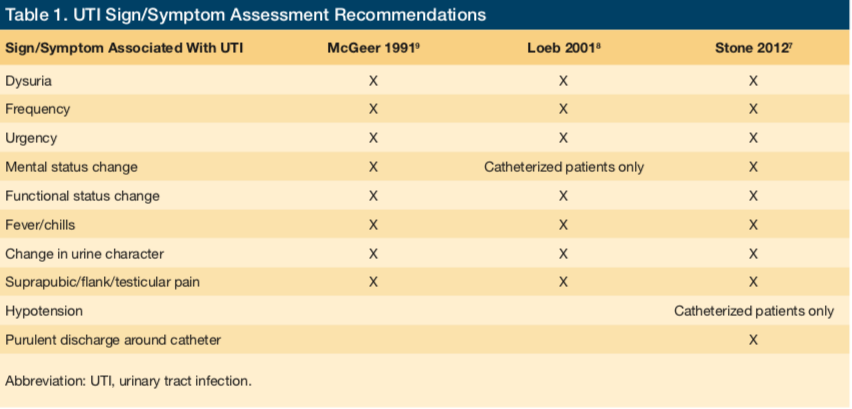

Several sets of S/S consensus criteria exist (Table 1).6-9,11,16 For over two decades, the McGeer form, based on the information presented in McGeer et al,9 has been the gold standard for UTI surveillance in LTC residents. While its reliability has been established with wide usage, its diagnostic accuracy has been shown to be low.23 This project’s algorithm was developed by starting with the McGeer criteria and adding the newest, evidence-based information from the latest established guidelines.6-9 McGreer criteria is used for multiple types of infections and have been used nationwide for more than 20 years.6,8,9,16

The assessment procedure is detailed in Box 1. Collectively, guidance on UTI assessment indicates that at least one new or acutely worse genitourinary S/S should be present in combination with other typical or atypical S/S, although there is variation in which S/S must exist, in what order, and the number needed to diagnose UTI. Typical S/S include dysuria, frequency, urgency, new flank/suprapubic/testicular pain, and urine character change. Atypical symptoms include fever and worsening mental or functioning status. For catheterized residents, purulent discharge at the insertion site, hypotension, and chills also may be seen.

Staff Education

The didactic education strategy consisted of a mandatory in-service training and occurred a month prior to implementation. Nurses and providers were educated one time during a 45-minute session that included didactic instruction (via PowerPoint presentations), case studies, handouts, and a pre- and post-education knowledge test. Class instruction, conducted by the primary investigator, focused on promoting understanding of the best available evidence, including how ASB differs from UTI, UTI S/S, and how inappropriate antibiotic treatments affect residents. Participants were also instructed in how to use the Cooper Tool and were informed of expected outcomes from the quality improvement project.

Change Champions

Change champions were used to improve uptake and use of new knowledge and included nine people: the project leader, director of nursing, infection control nurse, and unit registered nurse managers. Change champions are individuals chosen to promote an implementation process by circulating information about it, encouraging peers (staff nurses) to adopt it, and providing demonstration and clarification.24,25 When these key persons support innovation, its adoption is more likely.26 Change champions are best used in patient areas where an implementation is taking place. These individuals agreed prior to the staff education to be in this role and met with the project investigators on a few occasions and then monthly from December 2012 to April 2013 (before and during implementation).

Data Collection and Measures

A 3-month retrospective review was performed on data from LTC resident charts, pharmacy and laboratory reports, and infection surveillance forms (the McGeer form pre-implementation and the Cooper Tool post-implementation). LTC residents were defined as those residing in the facility greater than 30 days. Rehabilitation residents were excluded. Pre- and post-implementation measurements were performed exactly 1 year apart to exclude any potential seasonal variation. Pre-implementation data were extracted from February 2012 through April 2012, and post-implementation data from February 2013 through April 2013.

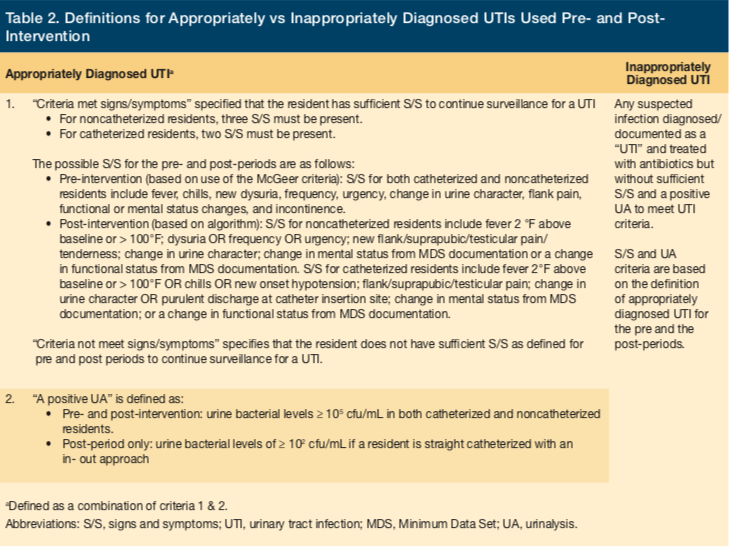

We used five outcome measures to assess the success of the project: three clinical measures (number of UTI diagnoses, proportion of appropriate vs inappropriate UTI diagnoses, and number of UA tests); one process measure (provider adherence to the algorithm); and one educational measure (nurse and provider knowledge). The number of UTIs included all infections labeled as UTI, both appropriate (met and UTI criteria) and inappropriate (did not meet UTI criteria), in both the pre- and post-periods. The number of UAs included those with or without a culture and sensitivity. The percentage of inappropriate antibiotic treatment prescriptions for UTI was calculated using the number of UTIs inappropriately treated divided by the total number of UTIs. Table 2 provides definitions for appropriately vs inappropriately treated UTIs. The Fisher’s exact test was used to determine statistical differences for the three clinical outcome measures.

The process measure (provider algorithm adherence) was calculated in the post-implementation period to determine the rate at which nurses were using the algorithm when a UTI was suspected. Suspected UTIs were identified on patient charts based on a colored-dot system for monitoring; a purple dot signified suspected UTI. If a resident was being monitored for suspected UTI, charts were reviewed daily. To objectively assess adherence, all monitoring forms were turned into a box for the infection control nurse—whether patients were diagnosed and treated for UTI or not. But we also measured adherence subjectively by simply asking nurses how often they adhered to the algorithm.

Nurse and provider knowledge was measured using a test that was administered three times: pre-education (to determine baseline knowledge), post-education (to assess for improved knowledge), and within one week of project completion (to determine knowledge retention).

The knowledge assessment test was given in paper format immediately at the beginning of the education session and then again immediately after the education session. At these two points, the test consisted of 10 questions related to differentiating between ASB and UTI acquisition, assessment and procedures, and treatment.

The test was given a third time within a week of the intervention monitoring end date (April 30, 2013). The third test administration was the same test but with two additional questions regarding adherence to the dot system and feedback on the intervention itself. The third and final time, we handed out a paper copy of the test to all staff from the education session with a deadline to return the test to a box anonymously, but not all nurses and providers turned the test in the third time. Each test was manually scored and an average of the total scores was determined.

Results

Resident Demographics

The average resident census was 100 in the pre-implementation and 83 in the post-implementation. An independent Sample’s t-test showed that there was a statistically significant difference between pre- and post-periods (t = 14.422; df = 3.485; P ≤ .001). The resident room matrix was changed to allow for more rehabilitation and less LTC beds in July 2012, which explains this difference.

The average resident age was 82 in the pre-implementation period and 87 in the post-implementation period (t = 1.995; df = 61; P = .51). Resident gender was 22% males and 78% females in the pre-implementation period and 19% males and 81% females in the post-implementation period. The Fisher’s exact test showed no statistical significance in gender differences between the two periods (P = .764).

Outcome Measures

Using Fisher’s exact test, the number of UTI diagnosis decreased from 27 total diagnoses pre-implementation to 7 total in the post-implementation period, which constitutes a statistically significant difference (P < .001). In the pre-implementation period, 77.78% (n = 21) of UTI diagnoses were inappropriate compared with only 14.29% (n = 1) in the post-implementation period, a statistically significant difference (P = .004). The number of UA testing decreased from 35 total tests pre-implementation to 18 total tests post-implementation, although this was not a statistically significant difference (P = .251).

For the process measure, adherence to the algorithm, we found that the algorithm was used in 86% of the cases in which residents were being monitored for UTI.

Average scores on the knowledge assessment tests improved from the pre-education (49%) to the post-education (73%) periods but fell slightly (63%) in the post-project period.

Discussion

The purpose of this quality improvement project was to address the insufficient assessment of LTC residents with suspected UTI by implementing a multifaceted, evidence-based program in order to give nurses a framework for understanding the clinical issue, clear assessment criteria, and a well-defined process for ensuring patients received appropriate diagnoses. The Cooper Urinary Surveillance Tool also allowed the providers to track residents with a UTI throughout their treatment on a single, comprehensive form.

The pre-post analysis showed that this program significantly reduced the rate of UTI diagnoses and reduced inappropriate diagnoses for suspected UTIs, and improved nurse and provider knowledge. While the post-implementation reduction in UA rates was not statistically significant, the 97% decrease in UA testing did represent a cost savings for the facility.

A primary goal of our project was to decrease inappropriate antibiotic use in LTC residents with suspected UTI, which can lead to fewer adverse effects, lower incidence of C diff infections, decreased antibiotic resistance, and fewer state citations. Because antibiotic overuse is so common in LTC, it is important to understand contributing factors. For example, it is common for a urine dipstick or UA test to be performed when a LTC resident has a mental or functional status change without other S/S. Clinicians often associate delirium and cognitive/functional decline with UTI, although worsening dementia, older age, severe illness, metabolic abnormalities, and/or psychoactive drug use also should be considered.27-29 While the literature supports mental status changes as one of the possible atypical and nonlocalizing S/S of UTI,30,31 such change alone is insufficient to lead to a diagnosis of UTI, even with a positive urine dipstick or UA. Functional declines, frequently cited by clinicians as a primary UTI symptom, also can be related to other causes such as reduced mobility, advanced age, history of cerebral vascular accident, Parkinson’s disease, and worsening dementia.3,6,32

Despite evidence-based guidance, LTC nurses often independently perform or order a urine dipstick or UA in the presence of only one S/S of UTI.7 When a resident has a positive urine dipstick or UA, nurses often call providers, who then order antibiotics to be started without confirming the resident is symptomatic. Thirty-eight percent of antibiotic treatments are based on nursing assessments given to off-site providers.13,33 Once positive results are seen on a urine dipstick or UA, the tendency to treat rises even without documented S/S.4,15,19 These reports suggest insufficient knowledge and resistance to change.

The literature supports that multifaceted approaches can improve outcomes.11,15 While the nurses’ consistent use of the algorithm contributed to the positive outcomes of our project, without the other strategies, the algorithm alone likely would not have had the same impact. It is believed that the reduction in inappropriate antibiotic treatments and UTI rates were a result of the project as a whole rather than just one of the individual components. For example, trying to implement the algorithm without education to explain its application or change champions to support its use would be difficult and could potentially lead to resistance to change.

Limitations of this project include the possibility that a Hawthorne effect may have influenced antibiotic prescribing behaviors, because providers were aware that UTIs and inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions were being measured. Moreover, neither the McGeer criteria nor the algorithm specifically address differences in the assessment of residents with and without a dementia diagnosis. The S/S criteria set forth in this project are based on UTI assessment research in LTC residents, but differentiation between residents with and without dementia has not been widely studied. More research is needed in the area of suspected UTI among LTC residents with dementia. Extrapolation of findings and generalizability will need to be confirmed with duplication using the same multifaceted approach, possibly with a larger sample. This project has recently been duplicated in another LTCF.

Conclusion

The multifaceted approach to improving the identification, assessment, and management of UTIs in LTCFs proved to be a successful strategy in this project. While the developed algorithm was an essential part of the intervention, the staff education and use of change champions were important supportive interventions that increased adherence to the algorithm and its success in practice. We hope that the Cooper UTI Program can be used on a wide scale with greater diagnostic accuracy, allowing providers to make treatment decisions with more confidence. The algorithm, along with a multifaceted model for implementation, has the potential to reduce UTI rates, inappropriate antibiotic UTI treatments, costs, adverse effects, C diff incidence, and antibiotic resistance.

1. Center for Disease Control (CDC). Making health care safer: stopping C. difficile infections. CDC website. http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/hai/. Published March 2012. Accessed November 21, 2016.

2. Das R, Towle V, Van Ness PH, Juthani-Mehta M. Adverse outcomes in nursing home residents with increased episodes of observed bacteriuria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(1):84-86.

3. Buhr GT, Genao L, White HK. Urinary tract infections in long-term care residents. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27(2):229-239.

4. Rotjanapan P, Dosa D, Thomas KS. Potentially inappropriate treatment of urinary tract infections in two Rhode Island nursing homes. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):438-443.

5. Stevenson KB, Moore J, Colwell H, Sleeper B. Standardized infection surveillance in long-term care: interfacility comparisons from a regional cohort of facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26(3):231-238.

6. Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, Rice JC, Schaeffer A, Hooton TM; Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Society of Nephrology; American Geriatric Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(5):643-654.

7. Stone ND, Ashraf MS, Calder J, et al; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology Long-Term Care Special Interest Group. Surveillance definitions of infections in long-term care facilities: revisiting the McGeer criteria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(10):965-977.

8. Loeb M, Bentley DW, Bradley S, et al. Development of minimum criteria for the initiation of antibiotics in residents of long-term-care facilities: results of a consensus conference. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22(2):120-124.

9. McGeer A, Campbell B, Emori TG, et al. Definitions of infection for surveillance in long-term care facilities. Am J Infect Control. 1991;19(1):1-7.

10. Juthani-Mehta M, Drickamer MA, Towle V, Zhang Y, Tinetti ME, Quagliarello VJ. Nursing home practitioner survey of diagnostic criteria for urinary tract infections.

J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(11):1986-1990.

11. Loeb M, Brazil K, Lohfeld L, et al. Effect of a multifaceted intervention on number of antimicrobial prescriptions for suspected urinary tract infections in residents of nursing homes: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;331(7518):669-672.

12. Nicolle LE, Mayhew WJ, Bryan L. Prospective randomized comparison of therapy and no therapy for asymptomatic bacteriuria in institutionalized elderly women. Am J Med. 1987;83(1):27-33.

13. Pettersson E, Vernby A, Mölstad S, Lundborg CS. Can a multifaceted educational intervention targeting both nurses and physicians change the prescribing of antibiotics to nursing home residents? A cluster randomized controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(11):2659-2666.

14. Takahashi P, Trang N, Chutka D, Evans J. Antibiotic prescribing and outcomes following treatment of symptomatic urinary tract infections in older women. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2002;3(6):352-355.

15. Zabarsky TF, Sethi AK, Donskey CJ. Sustained reduction in inappropriate treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in a long-term care facility through an educational intervention. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(7):476-480.

16. Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). CMS Manual System, Pub. 100-07 State Operations Provider Certification, Transmittal 8. CMS website. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/Downloads/R8SOM.pdf. Published June 28, 2005. Accessed November 21, 2016.

17. Ouslander JG, Schapira M, Schnelle JF, et al. Does eradicating bacteriuria affect the severity of chronic urinary incontinence in nursing home residents? Ann Intern Med. 1995;122(10):749-754.

18. Schmiemann G, Kniehl E, Gebhardt K, Matejczyk MM, Hummers-Pradier E. The diagnosis of urinary tract infection: a systematic review. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107(21):361-367.

19. Phillips CD, Adepoju O, Stone N, et al. Asymptomatic bacteriuria, antibiotic use, and suspected urinary tract infections in four nursing homes. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12(73):73.

20. Titler MG, Kleiber C, Steelman V, et al. Infusing research into practice to promote quality care. Nurs Res. 1994;43(5):307-313.

21. Titler MG, Kleiber C, Steelman VJ, et al. The Iowa model of evidence-based practice to promote quality care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2001;13(4):497-509.

22. Doody CM, Doody O. Introducing evidence into nursing practice: using the IOWA model. Br J Nurs. 2011;20(11):661-664.

23. Juthani-Mehta M, Tinetti M, Perrelli E, Towle V, Van Ness PH, Quagliarello V. Diagnostic accuracy of criteria for urinary tract infection in a cohort of nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(7):1072-1077.

24. Ploeg J, Skelly J, Rowan M, et al. The role of nursing best practice champions in diffusing practice guidelines: a mixed methods study. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2010;7(4):238-251.

25. Titler MG, Herr K, Brooks JM, et al. Translating research into practice intervention improves management of acute pain in older hip fracture patients. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(1):264-287.

26. Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581-629.

27. Fong TG, Jones RN, Shi P, et al. Delirium accelerates cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurol. 2009;72(18):1570-1575.

28. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):780-791.

29. Voyer P, Richard S, Doucet L, Carmichael PH. Factors associated with delirium severity among older persons with dementia. J Neurosci Nurs. 2011;43(2):62-69.

30. Juthani-Mehta M, Quagliarello V, Perrelli E, Towle V, Van Ness PH, Tinetti M. Clinical features to identify urinary tract infection in nursing home residents: a cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(6):963-970.

31. Smith PW, Bennett G, Bradley S, et al; SHEA; APIC. SHEA/APIC guideline: infection prevention and control in the long-term care facility. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(9):785-814.

32. Nicolle LE. Urinary tract infections in older people. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2008;18(2):103-114.

33. Pettersson E, Vernby A, Mölstad S, Lundborg CS. Infections and antibiotic prescribing in Swedish nursing homes: a cross-sectional study. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008;40(5):393-398.

34. Juthani-Mehta M, Tinetti M, Perrelli E, Towle V, Quagliarello V. Role of dipstick testing in the evaluation of urinary tract infection in nursing home residents. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(7):889-891.