More Than Just Location: Helping Patients and Families Select an Appropriate Skilled Nursing Facility

Affiliations: 1Center for Aging Research, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN; 2Geriatric Medicine, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO

Abstract: The rapid evolution of the healthcare system is affecting how care is delivered to frail older patients. Most importantly, the length of a hospital stay for an episode of care is decreasing. This decrease has resulted in a larger proportion of older patients requiring a stay in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). Besides providing rehabilitation services, SNFs are required to provide complex acute and chronic medical care to their residents. SNFs vary in their strengths and weaknesses, and some may not be equipped to care for the complex needs of individuals who are ill. It is crucial that the healthcare system educates and assists patients, their family members, and members of the discharge team so that they can collaborate on finding the best SNF to meet the patients’ needs. In this article, the authors present evidence- and experience-based strategies that can guide hospitals to implement systems for facilitating the selection of the most appropriate SNF.

Key words: Care delivery, long-term care services, skilled nursing facility selection.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) are playing a larger role in the posthospital care of frail older patients than ever before.1 In 2011, 8.8% of all Medicare dollars were spent toward the care of patients admitted to SNFs compared with 6% in 2000.2 Moreover, a steady decline in the average length of hospital stay3 has resulted in more older patients requiring a stay in SNFs and a higher acuity among these patients, as evident by their higher case-mix indices.1,4,5 Not all SNFs, however, possess the capabilities and resources to meet the intense medical needs of these complex patients. Take this case vignette, for example:

An 85-year-old cognitively intact but frail female patient is admitted to the hospital for myocardial infarction and heart failure. She is later transferred to an SNF for 3 weeks of rehabilitation on account of her functional limitations, poor balance, and complex medication regimen. During a follow-up visit with her primary care physician after her discharge from the SNF, the patient and her daughter express discontent with the quality of care at the facility. Their complaints include unclean facility premises, a delay in services, several medication errors, and—most importantly—only one visit by the SNF physician during her entire length of the stay. They also express dissatisfaction with the hospital-to-SNF transition, alleging that the hospital team rushed them into selecting an SNF. They claim that on the day of hospital discharge, no relevant information was provided to them other than a list of nine SNFs that were near her home. The family had chosen this particular SNF based on its close proximity to the home of the patient’s daughter.

The individual described in the case vignette may have required daily weight-taking, frequent laboratory testing, and regular, frequent visits by the physician (as opposed to the once per month physician visit that is mandated by federal regulations). Selection of an SNF capable of providing the required intensity of care and supervision will require patients and their families to have in-depth information about the services that various SNFs offer. Without proper assistance and knowledge, families may select an SNF that is unprepared to meet the patient’s needs, which places the patient at risk for inadequate care and other complications, including rehospitalization.6-9

In 1976, the Subcommittee on Long-Term Care of the US Senate Special Committee on Aging opined the following: “To the prospective customer, the choice of a nursing home can be truly agonizing. Looks can be deceiving ... There is no way to tell what type of care is provided. Accordingly, patients and family must rely upon the judgments of physicians, social workers and ministers.”10 Although some guidance on the SNF selection process has been provided to families in the past,11,12 as needs and regulations continue to change, the experience of selecting an SNF continues to be pressured, complex, and traumatic.13,14 In this article, we provide an overview of the current practices, relevant regulations, and available tools for SNF selection and discuss possible best practices for assisting patients and families in choosing the most appropriate facility for their rehabilitation needs.

Current System and Governing Regulations

Hospital-to-SNF transitions are complex, and the exact roles of the discharge team members during these transitions remain ambiguous. Patients and families are often required to select an SNF on relatively short notice without the availability of a formal guiding process. Even patients with high premorbid physical and cognitive functioning may find it difficult to handle the pace of decision-making required during an acute hospitalization. Families may also be overwhelmed with the onslaught of information delivered by the hospital on top of the stress of having an ill family member. The time and attention devoted to the hospital-to-SNF transition is inconsistent with the critical nature of this decision,15 and patients are often unprepared to make educated choices.16 Fraundorf17 notes, “The decision to enter a nursing home involves a consumer who, almost by definition, is unable to manage his or her own daily affairs and who ill-informed, fearful, and often alone, is making (or at least participating in) a choice that leaves little room for error.”

Further complicating the discussion of hospital discharge planning for older adults is the increased use of observation status by hospitals. Medicare beneficiaries are eligible for SNF placement if they meet a number of requirements, but many families misunderstand one requirement in particular: qualifying hospital stay. Under Medicare, patients are eligible for SNF placement if they have 3 inpatient days in the hospital. Patients and families are often unaware that observation services in the hospital do not count toward SNF eligibility,18 and they may erroneously expect an SNF referral when other community services would be more appropriate.

Although recent research has helped to highlight the insufficiencies of and counter strategies for hospital-to-home transitions,19,20 limited evidence exists regarding best practices for hospital-to-SNF transitions. Currently, hospital systems weave their discharge processes around a set of Social Security Administration regulations referred to as “Free Choice by Patient Guaranteed.”21 Section 1802 of the Social Security laws state that individuals entitled to Social Security benefits may obtain health services from any institution, agency, or person qualified to participate under this title if such institution, agency, or person undertakes to provide him or her with such services.21 The freedom of choice concept is enforced by Section 482.32 of the Code of Federal Regulations from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which mandate that patients be provided with a list of available facilities and that “the hospital must not specify or otherwise limit the qualified providers that are available to the patient.”22 The CMS regulations also mandate that “the patient and family members or interested persons must be counseled to prepare them for posthospital care,” but other than the guidance that it be done as needed, the extent and nature of this counseling is not specified.

In May 2013, the CMS updated its interpretive guidelines for hospital discharge planning, which includes some information on SNF referrals.23 In brief, this document outlines the requirements for hospitals to provide a more formal and written discharge planning process with the expectation to assess the posthospital needs of the patient, to ensure that postacute facilities can meet those needs, and to provide a list of facilities based on geographic proximity to the patient’s home. It also suggests that the discharge planner refer the patient to the CMS Nursing Home Compare website (discussed later in the article), but it does not discuss good guidance procedures for SNF referrals, nor does it cover the importance of allowing adequate time for patients and families to choose an appropriate SNF. Hence, if patients fail to receive sufficient information, they may base their selection on factors such as an SNF’s proximity to their own home or to a loved one’s home rather than on the quality of care it offers—a strategy that may result in a poor selection.6

Decision-Making Process for SNF Selection by the Patient

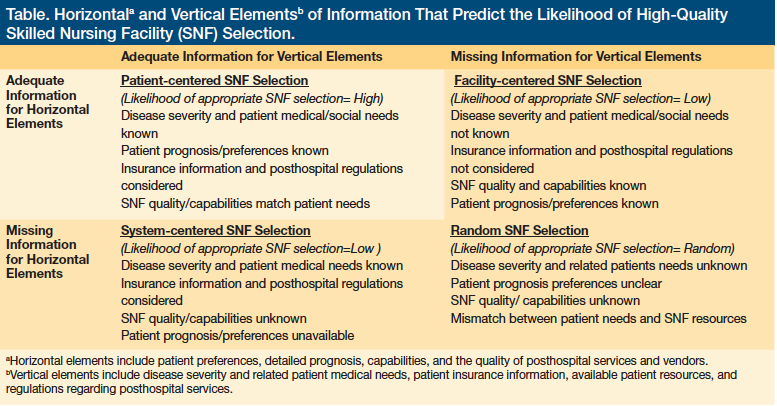

It is understood that families often face stress, shame, guilt, and frustration when deciding to place their loved one in an SNF for a long-term stay,24 but little is known about the elements of the SNF selection process for selecting a high-quality SNF for postacute rehabilitation. Based on our observations, various elements of this selection process may be divided into two groups: vertical elements and horizontal elements (Table). The vertical elements include discussions about patients’ medical needs and the resources available to them, patients’ disease severity (eg, stage of heart failure, stroke severity), their health insurance details, and the basic regulations about posthospital services.

The horizontal axis represents discussions about patients’ detailed prognoses, their preferences for treatment, and in-depth analysis of the quality of various posthospital options, including detailed information about SNF capabilities (eg, physician supervision, ability to perform daily weights, ventilators), the quality of staff at the SNF (see Education of Care Team section for additional information), and staffing levels. For the most part, the vertical elements are prerequisites for hospital discharge and, more often than not, are addressed. Conversely, the horizontal elements that facilitate the selection of higher quality and individualized posthospital options, such as an SNF or home health care agency, may be skipped. Effective discussions about the latter elements may require well-trained discharge teams. As described in the Table, the extent of emphasis (or lack thereof) on the vertical, horizontal, or both elements may result in a spectrum of success with the discharge process. Based on our observations, it may range from a “patient-centered” discharge process to a “random” discharge, with the latter having a high possibility of inappropriate selection, resulting in poor or even harmful care. An inappropriate selection (“facility-centered selection”) may also result when families make a decision based primarily on patient and family wishes rather than disease process and medical needs.

Tools to Educate Patients and Their Families About the Horizontal Elements

As previously noted, CMS places the onus of providing timely, available, and appropriate posthospital options to patients on the hospital discharge team. The discharge team can use and distribute to patients and their families several available resources and tools that may aid in obtaining the aforementioned horizontal information pieces:

Nursing home scorecards. In 2007, CMS unveiled the publicly reported SNF scorecard known as Nursing Home Compare, which provides a five-star rating system for ranking all licensed SNFs in the United States. This composite scoring system is based on the facility’s performance on three performance measures: (1) SNFs’ performance in health inspections (highest weight); (2) staffing levels; and (3) overall score on a set of quality measures (least weight). This tool provides crucial information about SNFs in a given area (eg, number of beds, deficiencies in the last survey, recent complaints filed by consumers, staffing levels). Moreover, consumers can use this website to make side-by-side comparisons of several SNFs. It has been recommended that consumers review the best performers and the worst performers rather than focus on the whole range of SNFs.25 Although recent evidence points to a steady rise in the use of this scorecard and increasing confidence among consumers in this system,26 concerns exist about the accuracy of the final facility rank.25,27,28 For example, the evidence that a higher nurse staffing level per se will lead to better clinical care quality is mixed.29 Also, assigning a single-star rating may obscure differences between facilities in dimensions of care of greatest interest to a particular consumer.

State scorecards. Most states offer the federal survey score results on state-run websites. Some states have implemented more innovative approaches of presenting the quality data so that consumers can reassign SNF ranks based on their preferred order of several available quality indicators. For instance, using the State of Minnesota Nursing Home Report Card consumers can choose their top three most important quality measures and then find facilities that perform the best in those areas. Such innovative strategies are individualized and carry face validity, but their true impact on patient satisfaction and medical outcomes has yet to be studied.

SNF visits by family. A visit to one or more potential candidate SNFs by the patient’s caregivers is arguably one of the most crucial steps for the selection of a well-suited SNF.16 To ensure that caregivers have the time to make such visits before discharge, a hospital team needs to initiate discharge planning discussions earlier during the hospital stay. Once the family is informed of these recommendations, the Nursing Home Compare website provides consumers with a detailed checklist of questions to guide the families during their SNF visits. Some states, such as Indiana, are making patient and staff satisfaction survey results available publicly and to stakeholders as part of their value-based purchasing systems.30 Such sources that provide information on facility quality and performance can be invaluable aides to patients and their families in the selection process.

Streamlining the Discharge Processes

The described resources and tools can only be impactful in assisting patients and families in their selection of an SNF if the discharge teams incorporate the delivery of this information to patients into a streamlined and standardized discharge process. This process should begin as early as possible before discharge. The recent revision to the CMS State Operations Manual, as referenced earlier, emphasize that an evaluation of discharge needs be performed at least 48 hours before discharge,23 but—ideally—this should be done soon after admission. It will be crucial that discharge teams understand the described horizontal and vertical elements of hospital-to-SNF transitions to engage patients and families in their decisions.

Interpretation of regulations. It is crucial that hospital teams appropriately interpret regulations that pertain to postacute care discharge processes. The intent of the regulations is to minimize the potential conflicts of interest that may arise when arranging postdischarge care. The regulations encompass a wide range of postdischarge services, including specialist appointments, home health services, and durable medical equipment. If interpreted too narrowly, the SSA laws and related CMS regulations may hinder much-needed patient education and guidance for appropriate selection. If interpreted correctly, the law provides the flexibility to the hospitals to devise their own SNF lists and mechanisms to present these lists to the patients. One effective approach for discharges to SNFs could be to tier the lists on the basis of objective quality measures (eg, five-star rating, survey scores, hospital-created dashboards), provision of continuity of care (eg, facilities where the same hospital physician group will provide care), and geographic closeness to the patient’s or to his or her loved one’s home. To allay social workers’ and case managers’ concerns of violating the regulations, they could be provided with standardized scripts and handouts for patient information that are vetted by the hospital legal department. Thus, instead of simply providing a long list of SNFs and putting the onus of decision-making on the patients and their families, the discharge teams can share their burden by providing proper education and assistance in this critical process.

Education of care team. Effective guidance for patients and families requires an interdisciplinary approach. All of the team members, including physicians and nursing staff, should receive education about the described elements of the postacute discharge process, and their roles in the discharge process should be well defined. For example, social workers are highly qualified to lead discussions about posthospital insurance coverage and out-of-pocket costs for posthospital services, whereas physicians are experts in disease severity and postdischarge medical needs. All team members could benefit from education about the SNF star-rating systems and other horizontal elements of the discharge process. Physicians who are trained in postacute care (eg, geriatricians, physiatrists) could facilitate the training of discharge teams, particularly with regard to the SNF environment, quality assessment of area SNFs, and understanding the role of SNFs in a patient’s rehabilitation.

Patient and family education. Patient and family education regarding the discharge process and their posthospital needs is crucial and should occur early in the hospital stay. The education should include open discussions that cover several topics, including the role of SNFs in rehabilitation, role of various interdisciplinary team members in an SNF, interpretation of five-star ratings, importance of facility visits, and implications and taboos associated with an SNF discharge. Timely discussions should allow time for families to tour shortlisted facilities and to make their choice in an unrushed manner.16 As previously mentioned, the checklist available on the Nursing Home Compare website guides the patient’s family and friends in asking relevant and crucial questions during an SNF visit. Despite the education provided by the discharge team, some families might still select a facility based purely upon geographic location and personal preference, a decision that the discharge teams should respect.

Conclusion

SNFs vary in the breadth and quality of services they provide for frail postdischarge patients. Pressures are increasing on hospitals to choose postdischarge partners that are invested in better care delivery. Many hospitals are implementing postdischarge mechanisms to empower these partners to take better care of postdischarge patients. Prompt and high-quality discharge planning is a crucial piece of the postdischarge puzzle. The regulations pertaining to posthospital care discharge processes should be appropriately interpreted by discharge teams, and all team members, patients, and family members should be educated about the elements of the postacute discharge process.

References

1. Tyler DA, Feng Z, Leland NE, Gozalo P, Intrator O, Mor V. Trends in postacute care and staffing in US nursing homes, 2001-2010. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(11):817-820.

2. Medicare skilled nursing facilities. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareMedicaidStatSupp/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Statistical-Supplement-Items/2012SNF.html. Updated 2012. Accessed April 17, 2014.

3. Tistad M, Ytterberg C, Sjöstrand C, Holmqvist LW, von Koch L. Shorter length of stay in the stroke unit: comparison between the 1990s and 2000s. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2012;19(2):172-181.

4. Langer E, Drinka PJ, Voeks S. Readmissions and acuity in the nursing home—how will the nursing homes manage? J Gerontol Nurs. 1991;17(7):15-19.

5. Bohmer RM, Newell J, Torchiana DF. The effect of decreasing length of stay on discharge destination and readmission after coronary bypass operation. Surgery. 2002;132(1):10-15.

6. Angelelli J, Grabowski DC, Mor V. Effect of educational level and minority status on nursing home choice after hospital discharge. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1249-1253.

7. Castle NG. Searching for and selecting a nursing facility. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(2):223-252.

8. Grabowski DC. The admission of blacks to high-deficiency nursing homes. Med Care. 2004;42(5):456-464.

9. Grabowski DC, McGuire TG. Black-white disparities in care in nursing homes. Atl Econ J. 2009;37(3):299-314.

10. Subcommittee of Long-Term Care of the Special Committee on Aging; United States Senate. Nursing Home Care in the United States: Failure in Public Policy- Supporting Paper No.7. https://archive.org/details/nursicarei00unit. Published March 1976. Accessed April 18, 2014.

11. Larson LG. How to select a nursing home. Am J Nurs. 1969;69(5):1034-1037.

12. McAuley WJ, Blieszner R. Selection of long-term care arrangements by older community residents. Gerontologist. 1985;25(2):188-193.

13. Zarit SH, Whitlatch CJ. Institutional placement: phases of the transition. Gerontologist. 1992;32(5):665-672.

14. Ade-Ridder L, Kaplan L. Marriage, spousal caregiving, and a husband’s move to a nursing home. A changing role for the wife? J Gerontol Nurs. 1993;19(10):13-23.

15. Kane RL. Finding the right level of posthospital care: “We didn’t realize there was any other option for him.” JAMA. 2011;305(3):284-293.

16. Dove RW. Exploring the selection of a nursing home: who, what, and how. J Health Care Mark. 1986;6(2):63-66.

17. Fraundorf K. Competition and public policy in the nursing home industry. Journal of Economic Issues. 1977;11(3):601-634.

18. Skilled nursing facility (SNF) care. Medicare website. www.medicare.gov/coverage/skilled-nursing-facility-care.html. Accessed June 23, 2014.

19. Enguidanos SM, Brumley RD. Risk of medication errors at hospital discharge and barriers to problem resolution. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2005;24(1-2):123-125.

20. Greysen SR, Hoi-Cheung D, Garcia, et al. “Missing pieces” – functional, social, and environmental barriers to recovery for vulnerable older adults transitioning from hospital to home. J Am Geriatr Soc. Published online ahead of print June 16, 2014.

21. Compilation of the Social Security laws: free choice by patient guaranteed. Social Security Administration website. www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1802.htm. Accessed June 18, 2014.

22. Code of Federal Regulations, Section 42.483. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, HHS. www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2007-title42-vol4/pdf/CFR-2007-title42-vol4-sec482-43.pdf. Accessed April 18, 2014.

23. Hamilton TE; Center for Clinical Standards and Quality/Survey & Certification Group. Revision to State Operations Manual (SOM), Hospital Appendix A – Interpretive Guidelines for 42 CFR 482.43, Discharge Planning. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-13-32.pdf. Published May 17, 2013. Accessed June 23, 2014.

24. Dellasega C, Mastrian K. The process and consequences of institutionalizing an elder. West J Nurs Res.1995;17(2):123-136.

25. Phillips CD, Hawes C, Lieberman T, Koren MJ. Where should Momma go? Current nursing home performance measurement strategies and a less ambitious approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:93.

26. Harrington C, Collier E, O’Meara J, Kitchener M, Simon LP, Schnelle JF. Federal and state nursing facility websites: just what the consumer needs? Am J Med Qual. 2003;18(1):21-37.

27. Nazir A, Arling G, Perkins AJ, Boustani M. Monitoring quality of care for nursing home residents with behavioral and psychological symptoms related to dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(9):660-667.

28. Mor V, Berg K, Angelelli J, Gifford D, Morris J, Moore T. The quality of quality measurement in U.S. nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2003;43(2):37-46.

29. Spilsbury K, Hewitt C, Stirk L, Bowman C. The relationship between nurse staffing and quality of care in nursing homes: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(6):732-750.

30. Long term care consumer reports. Indiana State Department of Health website. www.in.gov/isdh/reports/QAMIS/ltccr/index.htm. Accessed June 23, 2014.

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to: Arif Nazir, MD, CMD, Sidney & Lois Eskenazi Hospital, 720 Eskenazi Avenue, 5/3 Faculty Office Building, Indianapolis, IN 46202; anazir@iupui.edu