Methylphenidate Augmentation for Treatment-Resistant Depression in an Elderly Patient With a Meningioma

Elderly patients with treatment-resistant depression and multiple comorbidities are challenging. We report an elderly man with a long history of depression, poor eating and sleeping, suicidal thoughts, and meningioma. The patient’s diagnosis and treatment were complicated by medical comorbidities, advanced age, and meningiomas of the brain, which limited treatment options such as electroconvulsive therapy. This patient had not responded to adequate doses of mirtazapine, bupropion, and risperidone/aripiprazole but showed significant improvement with methylphenidate augmentation after 2 weeks.

Key words: methylphenidate, augmentation, elderly, depression

The predominant symptoms of depression in the elderly include anhedonia, irritability, somatic complaints, anxiety, alterations in sleep and appetite, and suicidal ideation.1 It is crucial to differentiate medical conditions that can manifest as depression. Sensitive depression screening tools are warranted in a clinical setting to facilitate recognition of symptoms that may otherwise go unnoticed. Moreover, the vast majority of the geriatric population have multiple comorbidities that pose a challenge in the management of the depressive symptoms. Polypharmacy and medication interaction issues must be considered when deciding what medications to prescribe for these patients.

Treatment-resistant depression is lack of response to an adequate trial of an antidepressant medication.2,3 Numerous trials have determined that an adequate treatment duration of 6 weeks with an antidepressant is appropriate for recognizable improvement in depressive symptoms.4 However, patients vary in their response to antidepressant treatment and can be classified as responders or partial responders. Persistent depression that has inadequately responded to multiple treatment options pose a particularly tremendous challenge, despite new antidepressant medications. For these patients, switching antidepressants or adding a mood stabilizer, antipsychotic, or stimulant have demonstrated a satisfactory response for their depressive symptoms, function, and quality of life.2,5

We report the following case of a very elderly patient with a long history of depression, who was treated with multiple psychotropic medications including paroxetine, bupropion, mirtazapine, risperidone, aripiprazole, and psychotherapy with inadequate response eventually leading to suicidal thoughts/plans and psychiatric hospitalization. Treatment options were limited because of associated finding of multiple meningiomas in the brain.

Case Report

Our patient was an 89-year-old Caucasian man living in an adult home, who presented to the emergency room on December 11, 2015, with suicidal intent to overdose on pills. The patient expressed feelings of hopelessness and helplessness saying, “I want to finish my life; I can’t do it anymore.” He admitted to hearing voices of people he knew, noncommanding in nature, and seeing flashes of light. He was unkempt, depressed, anxious, withdrawn, and had psychomotor retardation. His psychiatric diagnosis prior to admission, as per the adult home records, was major depressive disorder. He had reported a history of depression from his 30s and was treated at different time intervals with paroxetine, bupropion, mirtazapine, risperdone, aripiprazole, and psychotherapy. His current episode started 1 year before, worsening in the couple of weeks prior to admission. He reported anhedonia throughout the day, hopelessness, insomnia, poor appetite, and loss of weight.

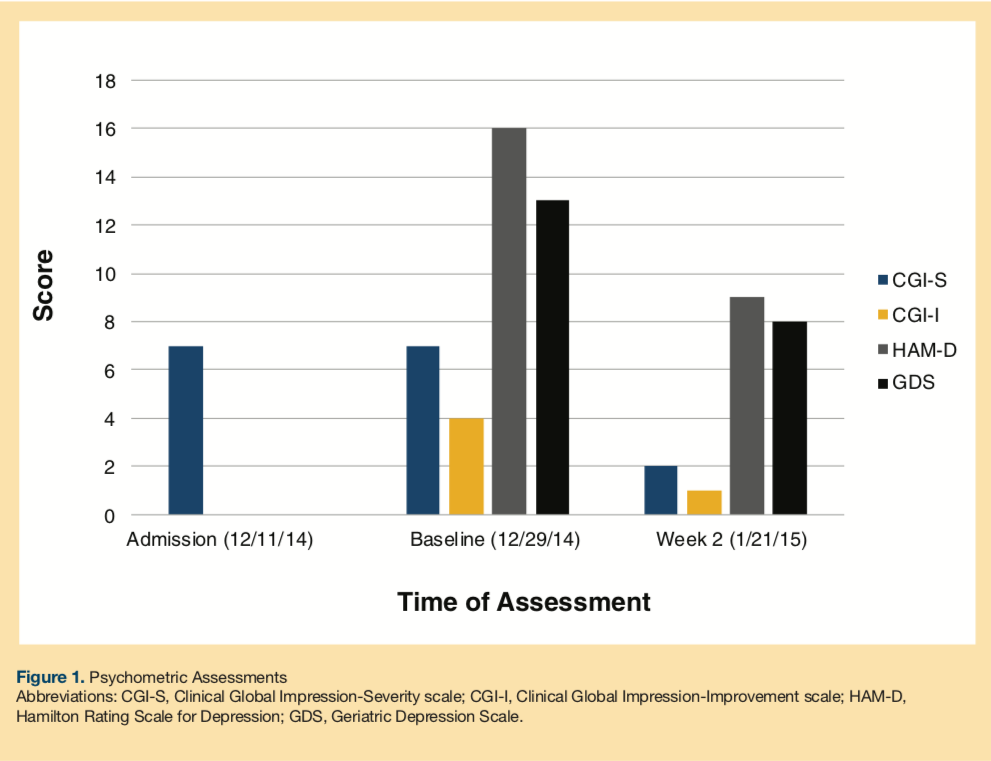

He was assessed using the Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale (CGI-S), the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D), and Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (Figure 1).6-8 His CGI-S upon on admission was 7 (among the most extremely ill patients). The patient had started to refuse treatment at the adult home. This was his first inpatient psychiatric admission for depression. No prior suicidal attempts were reported. There was no history of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. There was no family psychiatric history. His medical history included congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, gastritis, insomnia, benign prostatic hypertrophy, osteoarthritis, and scoliosis. He had no history of allergies. His medications at the adult home were risperidone 0.5 mg every night at bedtime (qhs), mirtazapine 45 mg qhs, zolpidem 5 mg qhs, valsartan 80 mg daily, sitagliptin 25 mg daily, omeprazole 20 mg daily, tamsulosin 0.4 mg qhs, and acetaminophen 650 mg twice daily. The physical examination and laboratory work, including comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, urinalysis, and electrocardiogram, did not reveal any significant abnormalities.

His CGI-S continued to be 7 at baseline. The Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale (CGI-I) at baseline was 4 (no change), the HAM-D score was 16, and the GDS was 13. He was placed on an observation schedule of every 15 minutes for safety. Risperidone 0.5 mg qhs was switched to aripiprazole 5 mg daily, and, subsequently bupropion 150 mg daily was added. Slight improvement in his sleep and appetite was reported. Psychomotor retardation persisted; he was seclusive and withdrawn. Despite medication adjustments, he continued to report depression and feelings of hopelessness. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was considered for his worsening depressive symptoms.

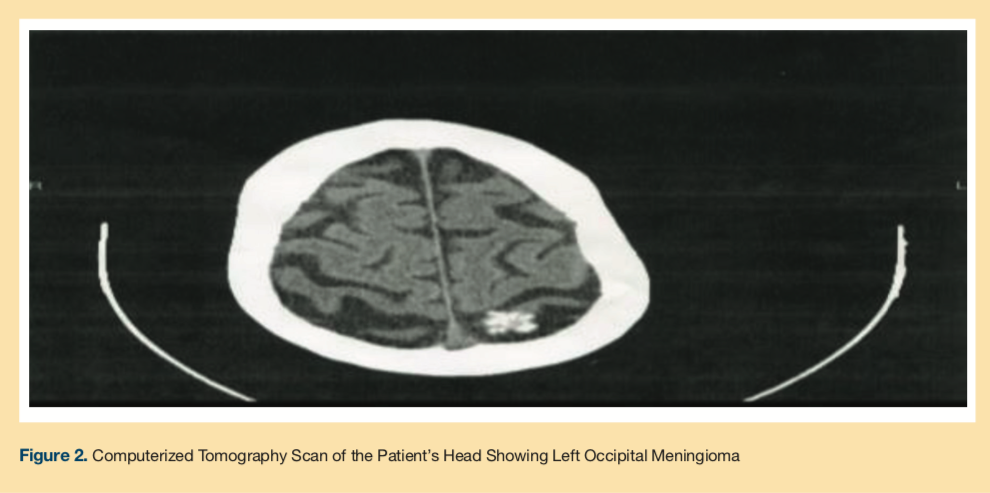

A computerized tomography scan of the head showed atrophy, left occipital meningioma (Figure 2), a calcified right intraconal mass, and mucosal thickening in the left maxillary sinus. Bupropion was discontinued, and methylphenidate 5 mg was started and titrated to 5 mg three times per day for 2 weeks. By Week 2, his CGI-S improved to 2, the CGI-I improved to 1, and the HAM-D and GDS scores were 9 and 8, respectively. The patient tolerated the medication and did not report any side effects. He was spending more time in the unit, attending activities, and socializing with the staff. Appetite, sleep, and mood improved. No suicidal ideation was reported. He denied any psychotic symptoms.

Discussion

Our patient presented with recurrent severe depression, worsened in the weeks leading up to his psychiatric admission. For the first time, he presented with psychotic symptoms which further complicated his presentation. His depression had not successfully responded to adequate trials of antidepressants and antipsychotic medications at the adult home. His age, comorbid medical conditions, multiple medications, medication adherence issues, and our incidental finding of a menigioma narrowed his treatment options.

Guidelines for managing treatment-resistant depression include pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches. A combination therapy adds a second antidepressant with a similar or different mechanism of action to attempt to stabilize dysregulated neurotransmitters. Augmenting pharmacotherapy with an antipsychotic, mood stabilizer, or psychostimulant attempts to target multiple receptors. Alternative nonpharmacological treatments include ECT, vagus nerve stimulation, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and psychotherapy.2,3,5

Mirtazapine is a potent serotonin 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, resulting in an increased serotonin 5-HT1A receptor-mediated transmission. Centrally, it is a presynaptic α-2 adrenergic antagonist, yielding an increase in norepinephrine. It has a high blocking affinity at the histaminergic receptors. It has no significant affinity for dopamine receptors and low affinity for muscarinic cholinergic receptors. Methylphenidate exerts its action by blocking the reuptake of both dopamine and norepinephrine. The augmentation effect of methylphenidate with mirtazapine may be secondary to the additive noradrenergic transmission by separate mechanisms. The onset of action is faster for the psychostimulant in comparison to the antidepressant, making it a good augmentation strategy in the treatment of depression.9,10 In medically ill depressed patients, methylphenidate has been found to be effective and safe in a review. The quicker onset of action of 2 to 5 days is an advantage over other antidepressants.11 The common side effects in the elderly include hypertension, tachycardia, insomnia, nervousness, anorexia, nausea, tremor, confusion, agitation, and psychosis.10

Apart from our previous case report,12 we have not come across any augmentation studies or case reports of mirtazapine with methylphenidate in elderly depressed patients. We did find a 4-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study examining the effects of methylphenidate as an add-on therapy to mirtazapine compared with placebo for treatment of depression in terminally ill cancer patients; a marked reduction in depressive symptoms at day 3 was reported in the methylphenidate add-on group.13 In addition, a recent double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study of elderly outpatients with major depression found that citalopram and methylphenidate combination showed statistically significant improvement in mood and well-being as well as a higher rate of remission compared with placebo. Improvement in cognitive functioning was noted with all groups.14 A 5-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, augmentation study with osmotic-release oral system (OROS) methylphenidate and antidepressant monotherapy in major depressive disorder—including patients who had failed one to three previous antidepressant monotherapy attempts—reported improvement of symptoms at day 14 in the OROS methylphenidate group compared with the placebo group. However, mean age of participants in this study was 45.6 years.15

Conclusion

Our patient’s diagnosis and treatment were complicated by his medical comorbidities, advanced age, and meningioma of the brain, which limited our treatment options including ECT. This patient, who had not responded to adequate doses of mirtazapine, bupropion, risperidone, and aripiprazole, did show significant improvement with methylphenidate augmentation in 2 weeks. Further controlled studies are needed to investigate our observation.

1. Taylor WD. Depression in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1228-1236.

2. Keitner G, Mansfield A. Management of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35(1):249-265.

3. Nierenberg AA, Katz J, Fava M. A critical overview of the pharmacologic management of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(1):13-29.

4. Desseilles M, Witte J, Change TE, et al. Assessing the adequacy of past antidepressant trials: a clinician’s guide to the antidepressant treatment response questionnaire. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1152-1154.

5. Thase M. Pharmacologic strategies for treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Ann. 2005;35(12):970-978.

6. Guy W. Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI). In: Rush AJ, ed. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:100-102.

7. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62.

8. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17(1):37-49.

9. Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB, eds. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology. 4th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2009.

10. Stahl SM. Stahl Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific basics and practical applications. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

11. Emptage RE, Semla TP. Depression in the medically ill elderly: a focus on methylphenidate. Ann Pharmacother. 1996;30(2);151-157.

12. Madhusoodanan S, Goia D. Rapid resolution of depressive symptoms with methylphenidate augmentation of mirtazapine in an elderly depressed hospitalized patient: a case report. Clin Pract. 2014;11(3):283-288.

13. Ng CG, Boks MP, Roes Kc, et al. Rapid response to methylphenidate as an add on therapy to mirtazapine in the treatment of major depressive disorder in terminally ill cancer patients; a four-week, randomized, double blinded, placebo controlled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(4):491-498.

14. Lavretsky H, Reinlieb M, St Cyr N, Siddarth P, Ercoli LM, Senturk D. Citalopram, methylphenidate, or their combination in geriatric depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(6):561-569.

15. Ravindran AV, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan MC, Fallu A, Camacho F, Binder CE. Osmotic-release oral system methylphenidate augmentation of antidepressant monotherapy in major depressive disorder: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(1):87-94.