Medroxyprogesterone Acetate Treatment for Sexually Inappropriate Behavior in a Patient With Frontotemporal Dementia

Affiliations: 1Department of Psychiatry, NYU Langone Medical Center, NY; 2Geriatric Services Unit, Central Regional Hospital, Butner, NC; 3Tanner Health System, Carrollton, GA; 4Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY

Abstract: Limited information is available on efficacious therapies for the treatment of sexually inappropriate behavior (SIB) in individuals with frontotemporal dementia (FTD), despite its high prevalence. The authors present the case of an elderly male resident with FTD who was transferred to their state psychiatric facility from an assisted living facility because of concerns of worsening SIB. He was successfully treated with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) after having an unsatisfactory response to a variety of psychopharmacologic agents and behavioral interventions. This case highlights the use of MPA as a safe and efficacious treatment for this behavior, and the authors provide recommendations for its use to target SIB in patients with FTD. The case also highlights the complementary role of behavioral interventions.

Key words: Sexually inappropriate behavior, hypersexual behavior, medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), dementia, frontotemporal dementia, behavioral interventions.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Sexually inappropriate behavior (SIB) is commonly categorized into three types: (1) sex talk incongruent to an individual’s baseline personality; (2) implied sexual acts, such as openly reading pornographic material and requesting genital care in the absence of a specific indication; and (3) overt sexual acts, such as masturbating and touching, grabbing, or disrobing oneself or others.1-3 The prevalence of SIB in individuals with dementia is estimated to be between 2.9% and 15%,4 with one survey reporting a prevalence as high as 25% among elderly male skilled nursing facility residents.2 In one study, patients with frontotemporal dementia (FTD) were more likely to exhibit acquired sociopathic behaviors than individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (57% vs 7%, respectively), which included some hypersexual behaviors (ie, extremely frequent or suddenly increased sexual urges or sexual activity) in the form of unsolicited sexual acts.5 It has been suggested that this type of behavior in individuals with FTD results not only from frontal disinhibition, but also from the alteration of one’s sexual drive due to disease involvement of the right anterior temporal-limbic region.6

Despite its high prevalence, there is limited information available on efficacious therapies for the treatment of SIB in patients with FTD. Additional challenges to managing SIB in these individuals include the lack of insight of patients with dementia and the difficulty maintaining a balance between ensuring the safety of others while avoiding the unnecessary use of restraints and medications that could cause adverse drug effects.7 A 2008 systematic review by Ozkan and colleagues3 described evidence for the use of the anticonvulsant mood stabilizers carbamazepine and gabapentin; the antidepressants citalopram, paroxetine, clomipramine, and trazodone; the antipsychotics haloperidol and quetiapine; the hormonal agents diethylstilbestrol, estrogen, leuprolide acetate, and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA); and the miscellaneous agents pindolol and cimetidine for the treatment of SIB in patients with dementia. These medications have been found to be helpful in various case reports and case series with sample sizes ranging from 1 to 39 patients; however, they are associated with several side effects, a discussion of which is beyond the scope of this article but is provided in the aforementioned review by Ozkan and colleagues.3

We present the case of an elderly man with FTD who demonstrated worsening SIB prior to being transferred to our inpatient psychiatric facility from an assisted living facility. To our knowledge, this is the first article in the literature to discuss the management of SIB in a patient with FTD using MPA complemented by behavioral interventions.

Case Report

A 67-year-old white man with a history of FTD was admitted to our state psychiatric facility from an assisted living facility due to concerns of worsening SIB. An incident at the patient’s assisted living facility involving an elderly, nonconsenting female resident with dementia reportedly being found naked in his room led to his transfer to the inpatient unit. Staff members had been concerned about the deterioration of his mental health and the safety of other residents at the assisted living facility.

Upon admission to our state psychiatric facility, the patient made several sexual remarks to the examiner during the physical examination, although he denied engaging in overt SIB. He manifested an otherwise restricted affect and a tangential thought process that occasionally responded to redirection back to the interview topic. His insight into the reason for his inpatient admission was poor. His records indicated that he had demonstrated paranoia toward staff members at the assisted living facility, but had no other psychotic symptoms at the time of admission. In addition, he had no history of agitation; no changes in sensorium, alertness, or sleeping pattern; and was independent in his basic activities of daily living.

The patient had been admitted to our facility 3 years before his current admission for behavioral disturbances, including hoarding, reduced ability for self-care, and cognitive decline. After an extensive dementia work-up that included imaging, neuropsychological testing, and use of the Neary criteria,8 he received a diagnosis of mild FTD with marked executive dysfunction affecting the frontal and temporal lobes. It was noted in his charts during that admission that he had touched his peers inappropriately on several occasions. Collateral information provided by the assisted living facility revealed that the patient had been experiencing ongoing, intermittent, worsening episodes of SIB with a decrease in his redirectability throughout the 3 years following his previous admission.

The patient’s psychotropic medications at the time of his current admission included divalproex sodium 1500 mg at night and risperidone 0.5 mg twice daily, both of which were reportedly prescribed for his SIB after an unsuccessful trial of serotonergic agents. His active medical conditions included type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. The patient had a history of childhood physical and emotional abuse, but not sexual abuse.

Upon admission, the patient was initially continued on his outpatient medications and was placed on one-to-one monitoring, whereby a staff member was assigned to observe him at arm’s length and was instructed to intervene as needed if he exhibited any signs of SIB. Results of the Frontal Assessment Battery9 (ie, a brief bedside cognitive and behavioral battery of six subtests to assess a patient’s frontal lobe functions) performed within a week of admission showed that the patient was in the mildly impaired range. The patient’s risperidone dose was increased because of his ongoing manifestations of SIB, but it was discontinued due to a lack of efficacy and the extrapyramidal side effects he experienced. Aripiprazole was initiated, but it also yielded no improvements in the patient’s symptoms after 3 weeks of use and was discontinued. The patient continued to manifest SIB, making sexual remarks and gestures; engaging in sexual acts; making impulsive, paranoid, and confabulatory verbal statements; and demonstrating irritability for several weeks after his admission. In addition, there were numerous episodes of medication refusals.

Given his ongoing behavioral disturbances and unsatisfactory improvement upon using psychotropic medications (ie, mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, serotonergic drugs), we considered treatment with hormonal agents. After obtaining an institutional ethics committee consultation and consent from the patient’s healthcare power of attorney, we decided to start him on MPA intramuscular (IM) injections, with the goal of helping him maintain safe behavior in a less restrictive living situation. We obtained the patient’s baseline hormonal levels and consulted with experts on the management of SIB in different patient populations. Our medical team reviewed the information and provided medical clearance, upon which the patient was started on a regimen of monthly MPA 150-mg IM injections. To avoid complications, he received monthly assessments of his testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and luteinizing hormone (LH) levels, as well as regular assessments of his prolactin levels (Table 1). Based on a report in the literature,7 we decided to start the patient on such a low dose and low frequency because we were concerned that the MPA might worsen his obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia. Our goal was to find the lowest effective dose. During this time, the patient continued to receive divalproex sodium.

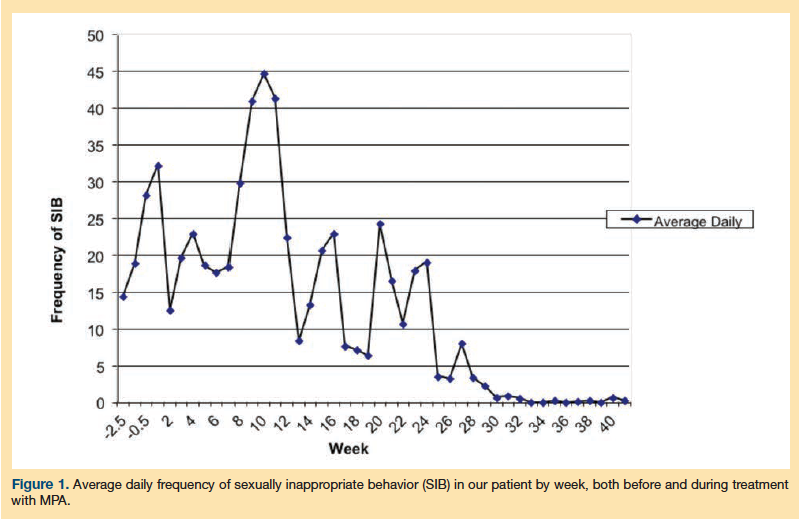

Figure 1 provides a summary of the average daily frequency of all four categories of behavior, as tallied for a 2.5-week baseline period prior to initiating MPA treatment and then weekly over the course of treatment. The team’s psychologist had helped devise a behavioral chart to document the frequency and severity of the patient’s SIB before and after MPA therapy as a means of objectively measuring the patient’s progress (Figure 2). In addition, behavioral guidelines to redirect the patient during these episodes and to minimize inadvertent reinforcement of verbal SIB were developed early in the course of his hospitalization and were continued and refined during his treatment with MPA; however, these guidelines were considered an adjunct treatment, with the MPA and close supervision for others’ safety being considered the patient’s primary interventions. Immediate verbal redirection (eg, reminders not to say certain things) was useful initially during his admission, but did not remain adequately effective because his SIB worsened during the first 3 months of admission. To address this issue, further redirection approaches were developed and formalized, which included distracting the patient with other (nonsexual) preferred activities, such as his favorite card game, walks, and time outdoors in the courtyard. Also, the staff selectively ignored his sexual comments to avoid reinforcing this behavior, while providing him with positive attention for engaging in the preferred nonsexual activities. Additional interventions were also developed to address concurrent behavioral disturbances during the course of this treatment, which included noncompliance with hygiene care (eg, bathing, changing soiled incontinence products or clothes) and medical procedures (eg, blood glucose monitoring, hormone injections). The interventions to address these noncompliance issues included a predictable schedule for self-care tasks and medical tests and procedures, and when he cooperated with what was required of him, he was rewarded with preferred snacks and nickels. These interventions yielded good results, with the nickels being an especially good motivator for him, as he saved them to give to his grandchildren.

As shown in Figure 1, the patient’s SIB was extremely frequent, averaging more than 10 incidents daily at baseline and during the initial treatment period. These SIBs ranged in severity from mild verbal comments to overt sexual actions. During the course of the next 12 weeks, the patient continued to manifest SIB, and the monitoring of his LH, FSH, and prolactin levels revealed that the monthly MPA injections did not maintain low levels of testosterone. The frequency of injections was therefore increased to once every 2 weeks. Approximately 4 weeks later, the patient was noted to have increased dysphoria, decreased involvement in activities on the unit, and worsening irritability, all of which improved after the initiation of low-dose sertraline (50 mg daily) followed by the addition of low-dose risperidone (0.5 mg twice daily).

The patient started to demonstrate gradual improvement in his SIB on the biweekly regimen of MPA over the next 14 weeks. This was marked initially by easy redirectability via distraction, followed by the absence of reciprocity at a sexual gesture made by a peer, and then an episode of a quick retraction and apology after he made a mild sexual remark to a staff member. By week 10 of MPA treatment, the patient began to demonstrate a reduction in his SIB, which was manifested by an objective reduction of behavior on the chart and a decrease in testosterone levels. He reached and sustained a near absence of SIB for several weeks prior to discharge, only rarely making an inappropriate verbal remark. The patient received a total of 20 injections while at the inpatient unit. His hormone levels (ie, testosterone, FSH, LH) were checked every month, and regular monitoring for medication side effects such as weight gain, worsening type 2 diabetes mellitus, and osteoporosis was conducted; none of these adverse effects were observed.

Based on the patient’s responses to behavioral interventions, distraction with preferred activities was identified as the most helpful behavioral strategy for addressing SIB by providing alternative positive social behaviors. These interventions appeared to be much more useful after the initiation of MPA treatment; food rewards, which he personally enjoyed, and nickel rewards, which helped him fulfill a personally valued role of saving up money to treat his grandchildren, were delineated as useful incentives to help him perform his activities of daily living and comply with his medication regimen. The patient was also gradually eased from very close one-to-one monitoring within reach, to one-to-one monitoring within eye view, to monitoring by nursing staff without needing an exclusive staff member assigned only to him. Thus, he was able to be cared for in a less restrictive manner and with a level of supervision that could become available outside of an intensive inpatient hospital setting.

The patient was discharged to an assisted living facility approximately 14 months after his admission to our psychiatric unit. Upon discharge, he was on a regimen of MPA injections every 2 weeks, divalproex sodium 1250 mg at night, sertraline 50 mg daily, and risperidone 0.5 mg twice daily. He has not had any repeat inpatient admissions for SIB.

Discussion

The presentation of SIB in nursing home patients can be highly distressing for other residents, family caregivers, and staff; however, there is little evidence-based information to guide management of SIB in cognitively impaired patients. Joller and colleagues1 reported that most articles about SIB have been single case reports or case series, and no randomized controlled trials have been published that assess the safety or efficacy of many proposed treatments for SIB. A recent literature review by Guay10 found only 23 case reports and case series that describe use of pharmacotherapy for managing SIB in patients with dementia. Further, generalizing the results of these case reports in the existing literature can be problematic, as many have been about SIB in older men, so it is unclear what effect the same treatment would yield in women.1

Nonpharmacological and behavioral approaches to managing SIB in patients with dementia are recommended before initiating hormonal treatments.1 Before implementing such approaches, an individualized assessment of the patient that takes into account cognitive decline and disinhibition is essential.1,11 Some effective behavioral interventions may include addressing environmental stimuli that trigger behaviors, distracting the patient with alternate activities, using stimulus control techniques, and providing the patient with opportunities to express his or her sexual urges in a more appropriate setting.1,11 The behavioral interventions we used for our patient were developed based on information from repeated individualized assessments and behavioral observations made by interdisciplinary staff, the patient himself, and the patient’s family. Findings on the neuropsychological assessments enhanced our understanding of his behavioral issues, their causes, and his abilities (eg, disinhibition leading to inappropriate sexual behaviors; stimulus-bound and perseverative behaviors leading to difficulty changing routines, such as for hygiene or lab schedules; an ability to learn some new information, such as routines and contingencies) and enabled us to gather information about his preferred activities, values, and premorbid personality (eg, such as his attachment to his grandchildren). In our patient’s case, emphasis was initially placed on prompting and attempts at controlling triggers and stimuli (eg, use of male staff to provide one-to-one monitoring whenever possible, reminders not to engage in certain behaviors in front of women). When these interventions were not successful, there was a move toward distraction and the provision of alternate positive activities rather than SIB; however, sexual behaviors can be powerfully reinforcing in themselves.12 Therefore, engaging the patient in alternative positive activities was more readily achieved when done in conjunction with hormonal treatment.

This case highlights the use of MPA to target SIB after unsuccessful trials of mood stabilizers, antidepressants, and antipsychotics; minimal effect from initial behavioral interventions; and initial lack of response to monthly MPA injections followed by improvements in SIB after an increase in the frequency of administration. MPA is a steroidal progestin that, by its inhibitory action on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axes, decreases a patient’s testosterone levels.13 MPA is commonly used in women in hormone replacement therapy, as contraception, and for the treatment of endometriosis. When administered in men, it decreases testosterone levels, lowering their sexual drives.7 Previous literature on the use of MPA for the treatment of SIB in persons with dementia suggests benefit with MPA at variable doses ranging from 100 mg IM monthly to 500 mg IM weekly.3,7 Some guidelines for the use of MPA in the treatment of SIB in patients with FTD are provided in Table 2.

The time to respond to MPA therapy distinguishes our patient from the patients discussed in previous case reports, who have reportedly shown resolution of SIB within 1 to 2 weeks. The development of our patient’s depressive symptoms during the trial of MPA is consistent with that reported in other cases; these cases also required augmentation with antidepressant medications. Weight gain, a frequently reported side effect of MPA, did not occur in our patient.7 There have been cases of discontinuation of MPA due to the ethical concerns related to chemical restraining.7

A 2012 study assessing the association of hormone therapy in postmenopausal women with venous thromboembolism suggested that the risk of adverse events was higher among users of estrogen and MPA (1 in 250 users) than among users of norethisterone/norgestrel (1 in 390 users), users of oral estrogen only (1 in 475 users), and nonusers (1 in 660 users).14 We were unable to find information on this adverse reaction specific to the use of MPA in the treatment of SIB.

Conclusion

Our case report adds to the growing body of literature demonstrating the safe and successful use of MPA to treat SIB, while also showing how this approach can be complemented by nonpharmacologic methods of redirection and rewards. Treatment with MPA was initiated in our patient only after unsuccessful trials with several other agents, and with careful attention to the patient’s rights via the involvement of the institutional ethics committee and consent from the patient’s healthcare power of attorney. The treatment protocol allowed for the safety of the patient via careful monitoring and the safety of others in his living environment via the reduction of exposure to his SIBs. The benefits of treatment in our case patient included the opportunity for more positive social interactions and roles as well as discharge from a restrictive psychiatric facility to a less restrictive environment at an assisted living facility. Further research into the long-term outcomes and tolerability of MPA, as well as the comparison with other hormonal agents, will contribute to the increased application of MPA in the treatment of SIB, a challenging behavioral concern in patients with dementia.

References

1. Joller P, Gupta N, Seitz D, Frank C, Gibson M, Gill SS. Approach to inappropriate sexual behavior in people with dementia. Can Fam Phys. 2013;59(3):255-260.

2. Szasz G. Sexual incidents in an extended care unit for aged men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31(7):407-411.

3. Ozkan B, Wilkins K, Muralee S, Tampi RR. Pharmacotherapy for inappropriate sexual behaviors in dementia: a systematic review of literature. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;23(4):344-354.

4. Tsai SJ, Hwang JP, Yang CH, Liu KM, Lirng JF. Inappropriate sexual behaviors in dementia: a preliminary report. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1999;13(1):60-62.

5. Mendez MF, Chen AK, Shapira JS, Miller BL. Acquired sociopathy and frontotemporal dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;20(2-3):99-104.

6. Mendez MF, Shapira JS. Hypersexual behavior in frontotemporal dementia: a comparison with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42(3):501-509.

7. Light SA, Holroyd S. The use of medroxyprogesterone acetate for the treatment of sexually inappropriate behavior in patients with dementia. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006;31(2):132-134.

8. Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1546-1554.

9. Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I, Pillon B. The FAB: a frontal assessment battery at bedside. Neurology. 2000;55(11):1621-1626.

10. Guay DR. Inappropriate sexual behaviors is cognitively impaired older individuals. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2008;6(5):269-288.

11. Fisher JE, Carstensen LC. Behavioral management of the dementias. Clin Psychol Rev. 1990;10:611-629.

12. Plaud JJ, Plaud DM, Kolstoe PD, Orvedal L. Behavioral treatment of sexually offending behavior. Mental Health Aspects of Developmental Disabilities. 2000;3(2):54-61. https://media.wix.com/ugd/e11630_4eafd3aa23d7efa996bb83224e13c8a0.pdf. Accessed October 22, 2013.

13. Brady BM, Anderson RA, Kinniburgh D, Baird DT. Demonstration of progesterone receptor-mediated gonadotrophin suppression in the human male. Clin Endocrinol. 2003;58(4):506-512.

14. Sweetland S, Beral V, Balkwill A, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk in relation to use of different types of postmenopausal hormone therapy in a large prospective study. J Thromb Haemost. Published online ahead of print September 10, 2012. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22963114. Accessed October 22, 2013.

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to: Meera Balasubramaniam, MD, MPH, NYU Langone Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, One Park Avenue, New York, NY 10016; meera.balasubramaniam@nyumc.org