Managing Risks in the Age of Social Media

ECRI Institute and Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging (ALTC) have joined in collaboration to bring ALTC readers periodic articles on topics in risk management, quality assurance and performance improvement (QAPI), and safety for persons served throughout the aging services continuum. ECRI Institute is an independent, trusted authority on the medical practices and products that provide the safest, most cost-effective care.

As social media engagement plays an increasingly bigger role in our personal lives, it should be no surprise that use is growing among older adults as well. According to the Pew Research Center, as of January 2018 (the most recent data available), 37% of adults aged 65 or older use at least one social media platform; the most common was Facebook, at 41%, followed by Instagram at 10%.1

The trend also applies to persons served by aging services provider organizations. Staff and organizations themselves are using social media as part of daily operations. Most health care organizations use social media for a range of functions from emergency response and crisis communication to an extension of marketing and public relations. Typical marketing uses include the following:

- Organizational news and services

- Sharing general news

- Community events and wellness programs

- Success stories

- Customer outreach and engagement

- Communicating information

- Recruitment purposes

- Philanthropy encouragement

Like many transformational technologies, social media has equal potential for good or harm. When used effectively, social media can allow an organization to communicate with residents, families, and the community; promote its wellness programs and services; market its brand; and encourage donations. Below, we provide an overview of potential risks from social media and summary of established regulations on use, so that organizations and staff can use and benefit from social media safely.

Potential Risks of Social Media

Misuse of social media by staff can lead to a wide variety of identifiable risks such as violations of resident privacy. With its focus on videos, photos, and storytelling, social media invites sharing of personal information where the information shared is actually protected health information (PHI), even when providers think they are protecting resident privacy. And the very attributes that make social media attractive—its immediacy and interactivity—can lead to other risks, such as users saying things intended to be under their own names but perceived to be an opinion or action on behalf of organizations they represent, which can lead to serious reputational damage.

Staff at nursing homes (NHs), in particular, have been the focus of several news articles detailing scenarios in which staff shared embarrassing photos of residents via social media sites, violating privacy laws and residents’ dignity. A 2015 ProPublica article found 35 instances between 2012 and 2015 in which workers at NHs and assisted-living centers had “surreptitiously shared photos or videos of residents, some of whom were partially or completely naked.”2

Such stories prompted the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to send a memo to its state survey agency directors to evaluate “nursing home policies and procedures related to prohibiting nursing home staff from taking or using photographs or recordings in any manner that would demean or humiliate a resident(s),” including via social media.3

Health care staff must be especially alert that anything they post to social media that involves their place of employment—for example, an anecdote about a resident or a photo from a party that may have residents in the background—has the potential to violate the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), even if they use the strictest privacy settings available on the social media platform where they are posting.

Some other concerns to be aware of include:

- Boundary issues

- Defamation and reputation

- Misrepresentation of the organization

- Caregiver distraction

- Medical liability

- Employment issues

- Network security

- Discovery risks

- Risks to confidential proprietary information

With this in mind, social media management has become an important enterprise risk management activity. Many accreditation, regulatory, and governmental entities, such as those below, now also include laws and standards related to social media that are applicable to all health care provider organizations due to continually changing or newly emerging risks.

Applicable Laws and Standards

HIPAA

HIPAA, as amended by the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009, mandates covered entities’ obligations concerning the privacy and security of PHI. HIPAA is broadly applicable to HIPAA “covered entities” (eg, individual health care providers, health care organizations, and their business associates).4 While the privacy rule addresses PHI in any form, the HIPAA security rules apply to electronic PHI that may be accessed, transmitted, received, or stored on electronic media.

HIPAA defines PHI as individually identifiable health information held or transmitted by a covered entity or its business associate, in any form or media, whether electronic, paper, or oral.5 HIPAA includes tiered penalties for violations of the privacy and security rules, from a civil fine of between $100 and $50,000 for each failure of a business, institution, or provider to meet privacy standards, up to a maximum of $1.5 million per year. Data breaches and noncompliance with federal health information privacy and security rules can lead to costly fines, settlements, or even criminal penalties.5

State Privacy and Security Laws

Some states have health information privacy and security laws and regulations that provide residents with greater protection than federal HIPAA regulations. For example, according to the American Health Information Management Association, many state laws mandate special protections and requirements related to certain “high-risk” records (eg, mental health, HIV, substance abuse treatment). Risk managers should consult legal counsel to determine whether their policies meet the requirements of relevant state laws.6

Because HIPAA is a federal law, it typically overrides contrary state laws; however, any provision of state law that is not contrary remains in full force. Thus, covered entities must follow applicable state privacy and security laws in addition to HIPAA.7

CARF-CCAC

The Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities–Continuing Care Accreditation Commission (CARF-CACC) requires that accredited facilities implement written procedures regarding communications that address social media. Such procedures might address the organization’s definition of social media, acceptable uses of social media, who has access and authority to post or modify privacy settings, parameters for communicating with current and potential residents, protection of health information, and how to manage violations of the policy. In addition, facilities must incorporate written ethical codes of conduct for social media use into their corporate responsibility efforts.8

National Labor Relations Act

The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) defines and protects the rights of private sector employees and employers in their labor relations, encourages collective bargaining, and seeks to eliminate unfair labor practices that are harmful to the general welfare.9 Under NLRA, certain work-related communications among employees conducted on social media may be considered protected “concerted activity.”

In 2011 and 2012, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) issued three reports involving 35 cases related to employees’ use of social media. Some of the early cases were settled by agreement, and others proceeded to trial before the agency’s administrative law judges and were appealed to NLRB. In 2012, NLRB began deciding cases involving employer discipline for employee social media postings, establishing precedent in this area of labor relations.10

NLRB cautions that social media policies should not be so sweeping that they prohibit the kinds of activity protected by the NLRA, such as employee discussion of wages or working conditions. NLRB also states that an employee’s comments on social media are generally not protected “concerted activity” if the comments are mere gripes not made in relation to group activity among employees.10

Joint Commission

Joint Commission’s standards mandate that health care organizations protect the privacy and maintain the security of health information, which, when taken broadly, applies to the use of social media. Other standards, such as those related to information management, resident rights, and leadership, can also be applied to the use of social media in health care.11 In addition, Joint Commission itself maintains several social media accounts, including a patient safety blog through which it conveys important information about the interpretation of its standards.

Recommendations

When developing a social media plan, organizations can start by identifying goals. Will the organization limit itself to passively monitoring social media, or will it be an active participant? Is the audience internal (eg, existing staff, clients, families) or external (eg, the local community)? Based on the answers to these questions, the organization will be able to identify the right tools to use and identify the resources, that is, the personnel, who will be in charge of monitoring social media activity and updating social media content, as appropriate.

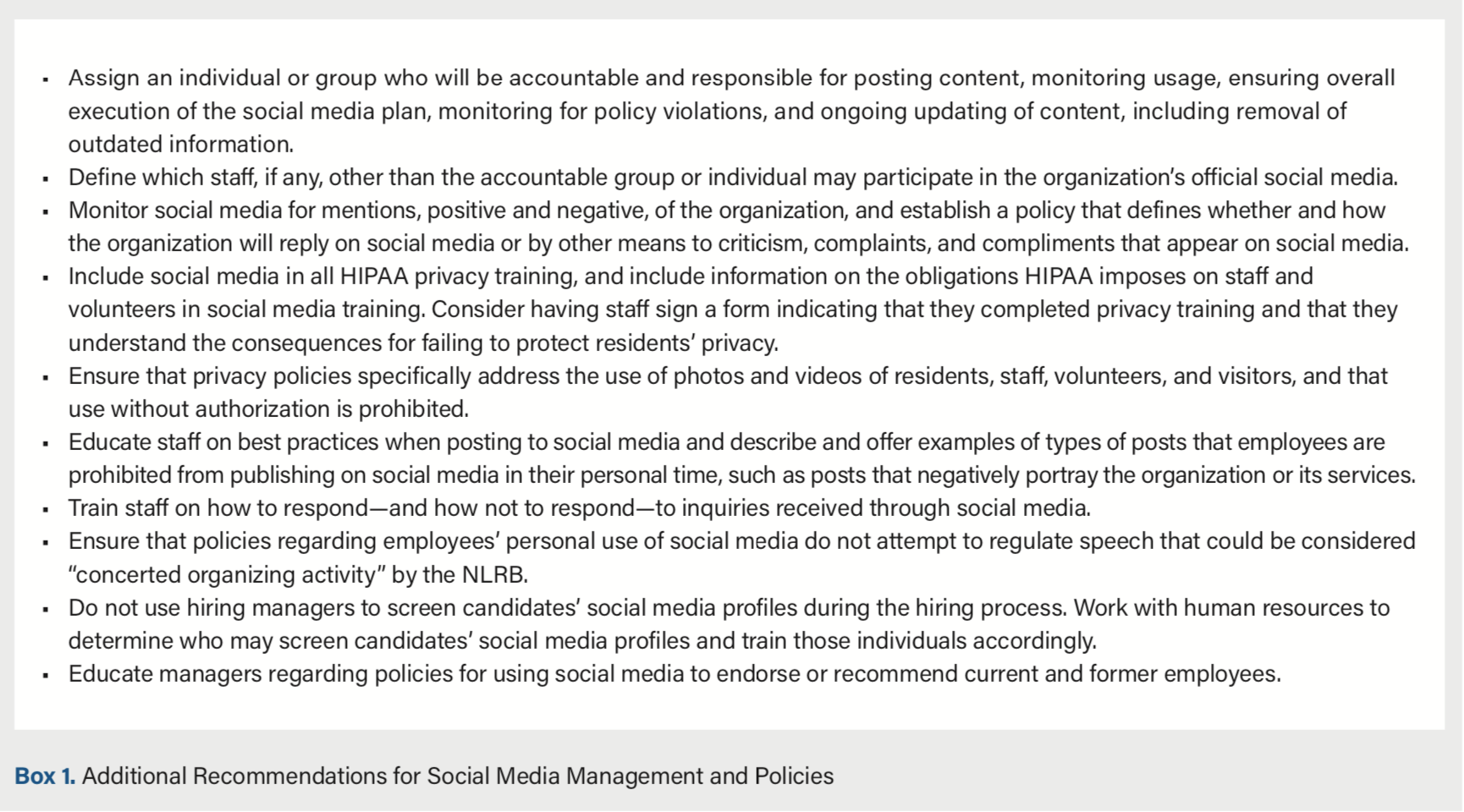

Organizations must also establish easily adaptable policies and procedures for addressing risks related to privacy, reputation management, and employment issues, and educate staff on these policies. They must establish how employees’ personal use of social media will be addressed (Box 1).

Policies should clearly address whether and how photos of residents can be taken and used. No photos of residents should be taken or used without residents’ explicit HIPAA authorization. Specific requirements for a HIPAA authorization are established in the HIPAA privacy rule. State law in some jurisdictions also requires the resident’s consent for use of his or her photos and images. The consent should specify how the photo will be used (eg, in a brochure, on a website, for clinical purposes). Staff who might seek to use existing photos for any purpose should check to ensure that the authorization covers a second use.

Conclusion

With social media consumption now seemingly ubiquitous, health care organizations must create and enforce social media plans, policies, and guidelines that define how engaged the organization will be, who its audience will be, and who will be responsible for managing and monitoring social media outlets. They must also establish easily adaptable policies and procedures for addressing risks related to privacy, reputation management, and employment issues, and educate staff on these policies.

References

1. Pew Research Center. Social media fact sheet. https://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/. Updated June 12, 2019. Accessed July 5, 2019.

2. Ornstein C. Inappropriate social media posts by nursing home workers, detailed. ProPublica.

December 21, 2015. https://www.propublica.org/article/inappropriate-social-media-posts-by-nursing-home-workers-detailed. Accessed July 5, 2019.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Protecting resident privacy and prohibiting mental abuse related to photographs and audio/video recordings by nursing home staff. cms.gov website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-16-33.pdf. Published August 5, 2016. Accessed July 5, 2019.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. HIPAA administrative simplification regulations, regulation text, 45 CFR § 160, 162, 164. hhs.gov website. https://www.hhs.govhttps://s3.amazonaws.com/HMP/hmp_ln/imported/hipaa-simplification-201303.pdf. Updated March 26, 2013. Accessed July 5, 2019.

5. Government Publishing Office. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, 45 CFR § 160.103 - Definitions. Govinfo.gov website. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2013-title45-vol1/pdf/CFR-2013-title45-vol1-sec160-103.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2019.

6. Hughes G. Mobile device security (updated). J AHIMA. 2012;83(4):50-55.

7. National Institutes of Health (NIH). How do other privacy protections interact with the privacy rule? privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov website. https://privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov/pr_05.asp. Updated February 2, 2007. Accessed July 5, 2019.

8. Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities–Continuing Care Accreditation Commission (CARF-CACC). 2017 CARF-CCAC continuing care retirement community standards manual. Tucson, AZ: CARF; 2017.

9. National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Basic guide to the National Labor Relations Act. https://www.nlrb.govhttps://s3.amazonaws.com/HMP/hmp_ln/imported/attachments/basic-page/node-3024/basicguide.pdf.

Published 1962. Revised 1997. Accessed July 8, 2019.

10. National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Fact sheets: the NLRB and social media. nlrb.gov website. https://www.nlrb.gov/news-outreach/fact-sheets/nlrb-and-social-media. Accessed July 8, 2019.