Leadership Collaborative Education Intervention to Enhance the Quality of End-of-Life Care in Nursing Homes: The IMPRESS Project

Affiliations: 1Department of Geriatric Medicine, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 2The Permanente Medical Group, Santa Clara, CA 3Veterans Administration Honolulu, Honolulu, HI 4Queens Medical Center, Geriatric Medicine Services, Honolulu, HI 5Kōkua Mau Hawaii’s Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, Honolulu, HI

Abstract: In the United States, many deaths occur in long-term care facilities, as this is the setting that many people find themselves in at the end of life (EOL). Engaging the leadership of nursing homes (NHs) in a collaborative fashion can enhance the implementation of quality EOL care. Through the IMPRESS (Improving Professional Education and Sustaining Support) project, researchers conducted an intervention consisting of quarterly collaborative educational sessions among five community NHs for approximately 10 months, during which education on evidence-based strategies and tools to improve EOL care was provided to participants. The authors found that these collaborative educational efforts of NH leadership resulted in statistically significant changes in the implementation of strategies to improve EOL care. The strengths and limitations of IMPRESS are outlined in the Project Pearls below.

Project Pearls

• The collaborative educational approach allowed each participating nursing home to tailor strategies and solutions to its own unique culture and needs, promoting healthy competition and accountability.

• Using existing educational resources from local providers and national organizations saved facilities time in producing their own set of materials.

• The success of this approach could be largely attributed to the motivation and enthusiasm of the nursing homes that volunteered to participate in this study; thus, lack of time and other staff priorities may be a more challenging barrier to overcome in other facilities.

• Implementation of this approach may be challenging in facilities that have a limited number of staff members who can serve as skilled team leaders and facilitators.

Key words: End-of-life care, hospice, palliative care, quality of care, quality of life, advance care planning.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

About 25% of deaths in the United States currently take place in long-term care facilities, and this number is expected to increase to 40% by 2040.1 Despite this rise, Teno and colleagues2 reported in 2004 that end-of-life (EOL) care in nursing homes (NHs) was perceived as poor with regard to unmet needs for pain control, being treated with respect, and quality of care, among other deficiencies, compared with other healthcare settings. Since this report, the Medicare hospice benefits have expanded considerably into the NH setting and have resulted in improved pain and symptom management for both hospice and nonhospice patients; however, NHs should not depend on hospice to assist them with EOL care. Ultimately, NHs are still responsible for many key aspects and processes toward improving EOL care quality, such as identifying residents approaching EOL, obtaining advance directives, providing adequate symptom assessment and management, providing a comforting and supportive environment, and making collaboration and communication more effective.3-7 Addressing these areas from a leadership and systems point of view can help NHs enhance palliative care for all residents under their care.

Some studies have reported an improvement in EOL care after educational interventions that included the training of leadership and nursing staff in NHs.6,8-10 For example, Levy and colleagues4 studied the outcomes of the MAPP (Making Advance Planning a Priority) program, which was implemented in a 160-bed NH in Colorado. The objectives of the MAPP program included identifying residents at high risk of death, informing attending physicians of residents’ mortality risk, obtaining palliative care or hospice consultation, and improving advance care planning documentation. The study found improvements in completion of advance directives, palliative care referral, and lower rates of terminal hospitalizations after the implementation of the MAPP program. Hanson and colleagues9 performed a quality improvement intervention that included the recruitment and training of palliative care leadership teams and staff. They compared seven intervention NH sites with two control NH sites. The outcomes measured were hospice enrollment, pain assessment and treatment, and advance care planning discussions. Researchers found an improvement in all of the outcomes in the intervention NHs compared with the control NHs9; thus, focusing on leadership engagement for the implementation of system changes has demonstrated effectiveness and is an important strategy in producing improvement in EOL care in NHs.

In this article, we present a different model of NH leadership engagement that seemed better suited to the NHs in our community. The approach was less prescriptive. In addition to enabling facilities to adapt strategies that fit their unique needs, this approach also provided them with the opportunity to share best practices and foster community collaboration.

The IMPRESS Project

We implemented a quality improvement approach that engaged leadership teams in creating structures and removed barriers to facilitate the delivery of quality palliative care in NHs through a collaborative, educational intervention of EOL care. We named the project IMPRESS (Improving Professional Education and Sustaining Support).11 Our educational approach had three main components: (1) engaging the leadership of NHs; (2) focusing on the implementation of system changes; and (3) collaborating with other facilities.

The University of Hawaii Institutional Review Board approved the IMPRESS project in June 2009. After grant funding was obtained, a call for participation was sent to several community NHs on the Hawaiian island of Oahu, where many of the nursing facilities are not part of any large national chains. These freestanding NHs often feel isolated from each other despite their common challenges. Facilities wishing to participate in the project completed an application form in which they had to indicate their commitment to the project and describe why they wanted to participate. Five NHs expressed interest and were enrolled in the project. No control facilities were enrolled, as each facility served as its own control. Leadership teams from each NH, which consisted of directors of nursing, charge nurses, social workers, and administrators (N=18), participated in four collaborative sessions conducted about 3 to 4 months apart, from June 2009 to April 2010. For the duration of the project, the leadership teams from the participating facilities remained stable. Each facility sent three or four members of its leadership team to the collaborative sessions. While not all team members attended all of the sessions, there were at least one or two members from each NH who consistently came to all of the sessions.

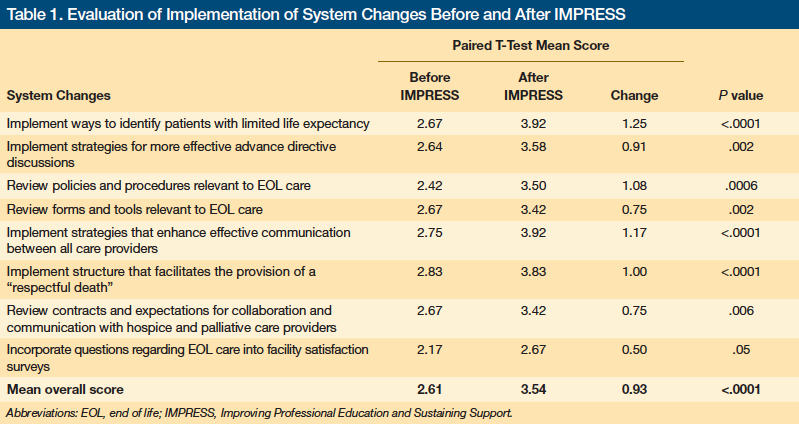

The participating facilities were provided with training on several evidence-based strategies and tools to enhance quality EOL care in NHs. Tools and evidence-based strategies covered in these sessions are listed in Table 1. Much of the content and resources for the collaborative sessions were based on the booklet Palliative Care in the Long-Term Care Setting from the AMDA—Dedicated to Long Term Care Medicine (formerly the American Medical Directors Association) Long Term Care Information Series. Additional resources from local hospice and palliative care organizations were also made available to these facilities. Rather than dictating a structured action plan, we allowed the facilities to select their own strategies for implementation that would best fit their setting. Open discussions during the collaborative training sessions provided opportunities for the participants to share their experiences and to learn from each others’ experiences. Dr. Wen led all four of the collaborative sessions.

Our Findings

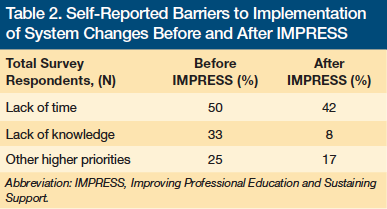

Pre- and post-session feedback forms were completed anonymously during the final collaborative session and were used to rate the effectiveness of the educational intervention. Significant improvements were found in scores for implementation of palliative care strategies in all eight areas before and after the educational intervention (Table 1). Common barriers to the implementation of quality EOL care as cited by the leadership teams included lack of time, lack of knowledge, and other higher priorities (Table 2). All perceived barriers decreased after the intervention; however, the lack-of-time barrier remained high even after the intervention.

Discussion

Our overall program objective of improving the quality of EOL care in NHs was achieved by using a collaborative educational approach among NH leadership. This intervention led to system changes, removed some of the common barriers to quality EOL care, and increased the implementation of palliative care strategies in community NHs.

We think that this novel approach was effective for several reasons. Rather than trying to dictate specific policies, forms, protocols, or strategies that may not have been easy to implement in each particular setting, this approach empowered participants to find solutions that fit into their own facility’s culture. Our model provided NH leadership with multiple resources and palliative care strategies. Practical tools from the literature and national resources were shared during the collaborative sessions. Our approach encouraged NHs to collaborate with community partners, and use educational resources from local hospice providers. Participating facilities were able to share their policies, procedures, forms, and best practices so that each NH did not have to create everything from scratch. This collaborative process promoted healthy competition and accountability and motivated facilities to “show off” their accomplishments, which inspired and encouraged others. Our approach also seemed to reduce barriers to implementation, as leaders from different NHs were able to share common challenges and potential solutions.

Study Limitations

We recognize that there may be some limitations to the generalizability of our approach and findings. There are a small number of NHs and participants, and regional and cultural differences may account for additional limitations. The collaborative environment may be dependent on many variables, including regional and cultural variables. Since the area involved in our study is more regionally isolated, for example, many of the local NHs are freestanding facilities with fewer than 300 beds; therefore, they often feel isolated and covet more educational opportunities. We recognize that successful collaboration also requires a skilled facilitator. While this was provided during the IMPRESS project, such facilitators may not be available everywhere.

In addition, the participating NHs were self-selected for motivation and readiness to implement changes to improve their palliative care processes. All of these factors may have created an environment that was more conducive to collaboration. Although we feel that the IMPRESS approach has the ability to provide lasting improvement in EOL care, the long-term impact of our project on improving the quality of EOL care will require further study that includes the measurement of patient outcomes and longitudinal follow-up of the participating facilities.

Conclusion

The approach we took with IMPRESS is ideal for smaller standalone facilities in regionally isolated areas, which are not connected to the larger NH chains, as such facilities generally welcome the opportunity for networking, collaboration, and access to more resources. While IMPRESS was facilitated by an academic institution, we envision that this type of collaborative approach to quality improvement efforts could be facilitated by regional quality improvement organizations or members of local chapters of key NH organizations, such as directors of nursing from the National Association of Directors of Nursing Administration in Long Term Care, administrators from the American Health Care Association, or medical directors from AMDA—Dedicated to Long Term Care Medicine. We also think that the model of quality improvement intervention demonstrated in the IMPRESS project makes efficient use of resources, is easy to implement, and can be expanded to other long-term care facilities.

References

1. Brock DB, Foley DJ. Demography and epidemiology of dying in the U.S. with emphasis on deaths of older persons. Hosp J. 1998;13(1-2):49-60.

2. Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291(1):88-93.

3. Flock P, Terrien JM. A pilot study to explore next of kin’s perspectives on end-of-life care in the nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(2):135-142.

4. Levy C, Morris M, Kramer A. Improving end-of-life outcomes in nursing homes by targeting residents at high-risk of mortality for palliative care: program description and evaluation. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):217-225.

5. Hanson LC, Eckert JK, Dobbs D, et al. Symptom experience of dying long-term care residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(1):91-98.

6. Caprio AJ, Hanson LC, Munn JC, et al. Pain, dyspnea, and the quality of dying in long-term care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(4):683-688.

7. Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB, Park PS, Morris JN, Fries BE. Estimating prognosis for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2734-2740.

8. Woo J, Cheng JO, Lee J, et al. Evaluation of a continuous quality improvement initiative for end-of-life care for older noncancer patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(2):105-113.

9. Hanson LC, Reynolds KS, Henderson M, Pickard CG. A quality improvement intervention to increase palliative care in nursing homes. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(3):576-584.

10. Vandenberg EV, Tvrdik A, Keller BK. Use of the quality improvement process in assessing end-of-life care in the nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005;6(5):334-339.

11. Wen A, Gatchell G, Tachibana Y, et al. A palliative care educational intervention for frontline nursing home staff: the IMPRESS project. J Gerontol Nurs. 2012;38(10):20-27.

Disclosures: The research outlined in this report was sponsored by the John A. Hartford Foundation Center of Excellence, Department of Geriatric Medicine, University of Hawaii, Honolulu; and Kōkua Mau Hawaii’s Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, which received grants for this project from the Chamber of Commerce of Hawaii and the Hawaii Community Foundation.

Address correspondence to: Aida B. Wen, MD, John A. Burns School of Medicine, Department of Geriatric Medicine, 347 North Kuakini Street, HPM9, Honolulu, HI 96817; aidawen@hawaiiantel.net