An Innovative Quality Assurance Activity to Reduce Urinary Tract Infection Rates in a Green House Skilled Nursing Setting

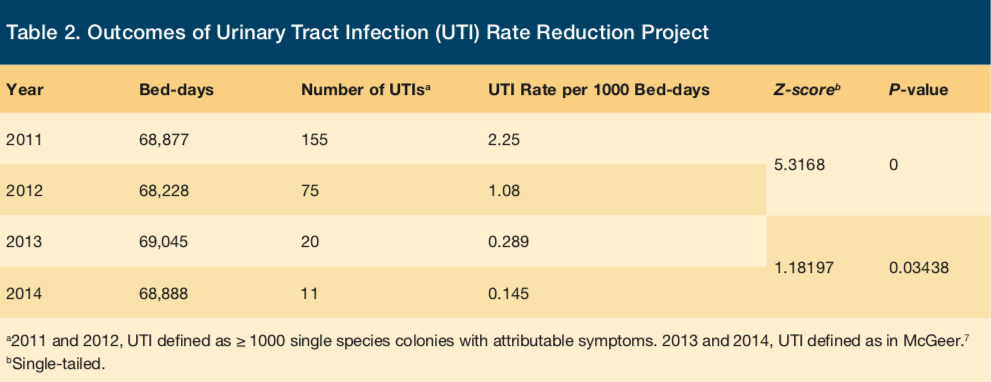

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are a source of discomfort as well as sepsis among older adults. We present a successful approach to UTI reduction from a 16 cottage, 192-bed skilled nursing Green House campus. Using an interdisciplinary problem-solving and educational approach, staff were able to reduce liberally defined UTI incidence between 2011 and 2012 from 2.28 per 1000 bed-days to 1.08 per 1000 bed-days (single tailed z-score, 5.3168; P = 0). When stricter McGeer criteria were used as part of an antibiotic stewardship effort between 2013 and 2014, the rate was further improved (0.289 per 1000 bed-days vs 0.145 per 1000 bed-days (z-score, 1.89197, P = .03438). This approach was replicated in an affiliated, non-Green House model 120-bed skilled nursing facility, and preliminary data there support its usefulness and portability.

Key words: urinary tract infection, antibiotic stewardship, skilled nursing facility, quality improvement

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are a source of discomfort and morbidity in the nursing home population. Data from the Minimum Data Set (MDS) estimate the annual likelihood of a UTI during a year of care to be 9.5%.1 A study in two New York City hospitals found UTIs to account for over half of all episodes of antibiotic-resistant septicemia.2 A large national sample of nursing facilities, home health care agencies, and hospices found UTI prevalence to be between 3.0% and 5.2%.3 The MDS study cited above also ascertained that staffing levels and UTI incidence are inversely proportional, suggesting that there may be modifiable aspects of care influencing the likelihood of a nursing home resident developing a UTI. Important to the national effort to reduce hospitalizations, Walsh and colleagues found that UTIs were one of the five most likely conditions leading to a potentially avoidable hospitalization from a nursing facility.4

The Eddy, a member of St. Peter’s Health Partners in the Capital Region of New York State, is a not-for-profit comprehensive network of geriatric care facilities and community services. Among our seven skilled nursing facilities, we noted in 2011 that one Green House campus had an excess of UTIs. In observing staff, we reached a tentative conclusion that the rate of UTIs could be reduced through improvements in our approach to perineal hygiene and through encouragement of improved hydration for our elders.

In this paper, we describe an interdisciplinary problem-solving approach to reduce the incidence of UTIs in a skilled nursing setting. We believe this approach to be a replicable model, and we present it in the hope that it may be helpful to others in the field.

UTI Rate Reduction Effort

Study Design and Setting

Eddy Village Green in Cohoes, NY, is composed of 16 cottages, each having 12 single bed rooms and a common kitchen, living, and dining area. Thus, there is a total of 192 beds, with average occupancy 98.5%. In 2011, at the initiation of the UTI reduction project, using liberal definition criteria as described below, the incidence of UTIs in the facility was 155 per 68,877 bed-days or 2.25 per 1000 bed-days. At that time we were intentionally tracking all pure culture results associated with fever or dysuria, in the hope of finding a correlation with falls and thus being able to intervene prior to a fall occurring. This was a consciously overly sensitive criterion to enhance case finding and, perhaps, fall prevention.5 We accepted any single-organism colony count of 1000 or greater, associated with symptoms including urinary frequency, dysuria, fever, abdominal pain, or fatigue or restlessness not otherwise explained, as a likely UTI. That year, we instituted an antibiotic stewardship program throughout our nursing home division, tracking all UTIs and use of antibiotics related to urinary symptoms and cultures.

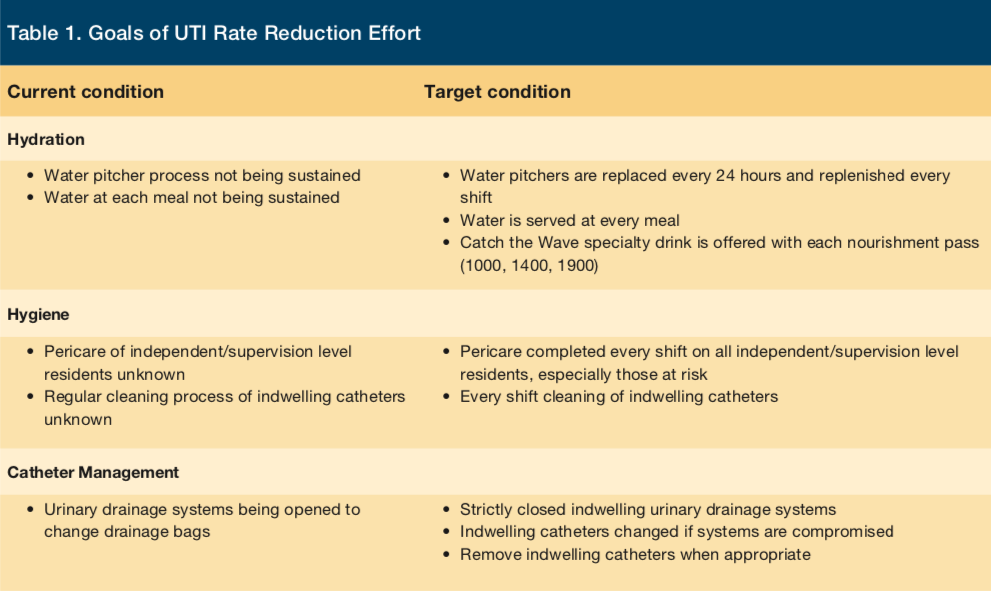

In the third quarter of 2011, we used the resulting, internally developed UTI Detail Report and the EQUIP Minimum Data Set analytics tool (LeadingAge, New York) report to initiate an audit of UTIs in each Green House cottage and to quantify the intake of oral fluids by elders in each house. Dietary staff, working with the registered nurse, infection control practitioner (ICP), nursing leadership, and direct care staff, increased the size of drinking glasses provided at meals and began to provide two glasses of fluids with each meal. In October and November of 2011, interdisciplinary meetings were instituted to review quality measures based on MDS data, with a focus on understanding the triggers of UTIs (Table 1).

In March 2012, the dietary department surveyed the use of sugary beverages in each house. The consumption of sugary fluids appeared to correlate with observed UTI rates on a house-by-house basis, upon analysis by the ICP and quality assurance (QA) specialist. Examples of sugary beverages included primarily soft drinks and fruit juices.

In April 2012, the team developed two new instruments: (1) the ICP developed an audit tool identifying other medical problems potentially contributing to recurrent UTIs as opposed to preventable nosocomial UTIs (eg, difficulty with perineal hygiene, inadequate hydration, diabetes mellitus, atrophic vaginitis); and (2) the QA specialist developed a mealtime hydration observation sheet. Two months of data were obtained, identifying beverage preference, amount provided, and amount consumed by each resident. The observation tool included a picture of different glass sizes and fluid levels to allow a clear visual approximation by direct care staff of the volumes consumed.

Additionally, on review of quarterly data, the ICP noted a correlation between UTIs and an elder’s independence in toileting and hygiene. In the Green House model, elder self-determination is a core value, but, due to this observation, care cards were standardized so that all elders who were identified as being independent or requiring verbal cues would be scheduled to be offered hygiene assistance by staff on each shift.

In May 2012, dietary and speech therapy staff provided an in-service program—entitled Dining, Dysphagia and Hydration—to all direct care staff. The course emphasized the importance of providing two nonsugary beverages (water, artificially sweetened soft drinks, or lightly fruit-flavored water) at each meal and additional beverages between meals. Also in May, there was a mandatory campus-wide educational program for all direct care staff regarding appropriate procedures for assisting male and female elders in perineal hygiene including proper infection control practices. This was a hands on demonstration including both demonstration to and observation of nursing assistants (Shahbazim) and licensed nursing staff.

In 2013, McGeer criteria were introduced for UTI surveillance use at the facility.6,7

In the first quarter of 2014, the ICP and QA team noted an increasing UTI frequency, as compared to the improved recent levels. Clinical documentation of fluid intake was facilitated through a collaborative initiative of the dietary and speech therapy departments, by introduction of a new data entry format on the facility’s electronic record system. Speech and dietary departments instituted campus-wide mandatory in-services regarding nutrition, hydration, and swallowing safety. In addition, a scheduled hydration program, “Catch the Wave,” was instituted in four of the 16 houses; then, in July, it was introduced throughout the campus. Infusion pitchers with attractive colors and low-moderate caloric content were placed in the common living areas of all the houses. Residents were encouraged to partake of beverages ad libitum but were also provided with scheduled beverages between meals.

Outcomes

As shown in Table 2, during the initial phase of this quality improvement process, when liberal criteria were applied for definition of UTIs, the rate of UTIs per 1000 bed-days was reduced from 2.25 in 2011 to 1.08 in 2012 (single-tailed z-score, 5.3168; P = 0). With revised criteria for UTIs, using the McGeer criteria during 2013 and 2014, the rate for UTIs continued downward from 0.289/1000 bed-days to 0.145 (single-tailed z-score, 1.8197; P = .03438).

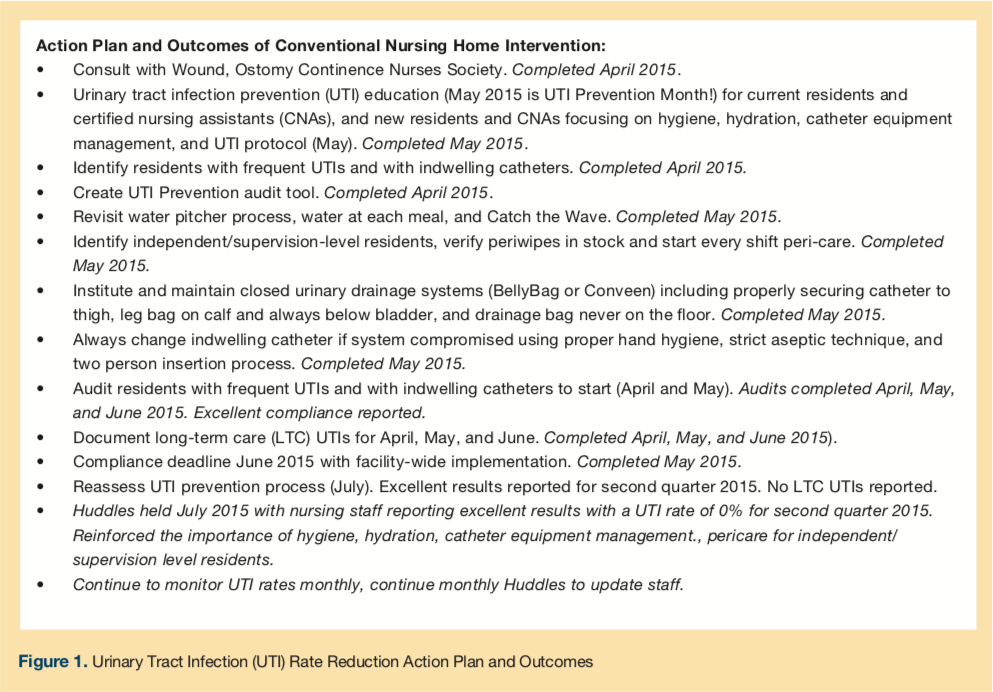

Modelled on our experience on the Green House campus, we also introduced an intervention at one of our other facilities, which has two 40-bed long-term care units and one 40-bed subacute care unit. The action plan and outcomes of the quality improvement project are detailed in Figure 1. We noted that six per 1000 residents were experiencing UTIs per quarter on the long-term care units. Staff education and hydration interventions similar to those described above were introduced in April 2015. There were no UTIs in long-term care residents of that facility in the second quarter of 2015. Subsequent ICP reports for the third and fourth quarters of 2015 reflected rates of 2.4 and 3.5 per 1000 residents, respectively.

Discussion

Through interdisciplinary discussion and multiple-department interventions that included dietary, speech therapy, nursing, and QA staff, we were able to achieve a marked reduction in UTI incidence among residents living on a 16 cottage, 192-bed Green House skilled nursing campus. We were able to demonstrate the transferability of the educational, hydration, and hygienic interventions to a more traditional skilled nursing facility. This process engaged multiple levels of staff and was sustained by re-education and re-emphasis of the importance of these specific interventions.

Basic tenets of geriatric care were relied upon: initiative by all disciplines; support of the independence and dignity of elders through respectful assistance with perineal hygiene; encouragement of appropriate wellness behaviors with respect to adequate oral hydration; and careful observation and sharing of data, first by manual and then by electronic means.

A weakness of this report is that it is derived from data obtained during administrative quality improvement activities, resulting in the initial use of nonstandard colony count criteria. However, a robust, continued decline of UTI incidence was seen once more standard criteria were adopted.

Conclusion

Simple, data-driven interventions of this type can lessen the morbidity linked to UTIs, thus improving the quality of life of older adults and potentially reducing hospitalizations and health care expenditures.

1. Castle H, Engberg JB, Wagner LM, Handler S. Resident and facility factors associated with the incidence of urinary tract infections identified in the nursing home minimum data set. J Appl Gerontol. 2015; http://jag.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/05/05/0733464815584666. Published online May 5, 2015. Accessed December 17, 2015.

2. Wolfe CM, Cohen B, Larson E. Prevalence and risk factors for antibiotic-resistant community-associated bloodstream infections. J Infect Public Health. 2014;7(3):224-232.

3. Dwyer LL, Harris-Kojetin LD, Valverde RH, et al. Infections in long-term care populations in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(3):342-349.

4. Walsh EG, Wiener JM, Haber S, et al. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations of dually eligible Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries from nursing facility and home- and community-based services waiver programs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(5):621-629.

5. Y Soliman, Meyer R, Baum N. Falls in the elderly secondary to urinary symptoms. Rev Urology. 2016;18(1):28-32.

6. McGeer A, Campbell B, Emori TG, et al. Definitions of surveillance in long-term care facilities. Am J Infect Control. 1991;19(1)1-7.

7. Stone ND, Ashraf MS, Calder J, et al. Surveillance definitions of infections in long-term care facilities: revising the McGeer criteria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(10):965-977.