Improving Outcomes Through a Coordinated Diabetes Disease Management Model

Affiliations:

1College of Nursing & Health Sciences, Texas A&M University, Corpus Christi, TX

2School of Nursing & Health Studies, University of Missouri, Kansas City, MO

Abstract: Nursing home residents are often medically complex, and there is a high prevalence of diabetes mellitus in the presence of one or more acute conditions. Outcomes for this patient population have been shown to improve with an interdisciplinary team approach to disease management. The authors conducted a quality improvement initiative that sought to measure and improve diabetes outcomes in a long-term care population at a corporately owned 112-bed nursing home located in South Texas. The team implemented evidence-based care using a specialized nurse practitioner within the coordinated diabetes disease management (CDDM) model. The AMDA – The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine (formerly the American Medical Directors Association) evidence-based diabetes guidelines were employed for clinical decision-making. The authors found that their project led to significant improvements in patient outcomes, including reductions in hypoglycemia incidence and sliding scale insulin orders, while increasing resident-centered care and improving chronic kidney disease screenings.

Project Pearls

•Nursing home residents with diabetes represent a heterogeneous population; thus, implementation of patient-centered disease management strategies is essential to improving outcomes and quality of life in this population.

•Use of a specialized healthcare practitioner to coordinate interdisciplinary diabetes care within the CDDM model facilitated patient-centered care and reduced the use of inappropriate oral medications and sliding scale insulin orders.

•Using the AMDA population-specific clinical practice guidelines for diabetes care ensured clinical decision-making and administration of patient-centered care was evidence-based.

•Implementation of this approach may be challenging in some facilities due to costs associated with having a specialized healthcare practitioner dedicated to diabetes management; however, the initial costs may be offset by long-term savings through improved health outcomes.

Key words: Care coordination, diabetes disease management, elderly, insulin, interdisciplinary diabetes care, quality improvement project.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

In the United States, the costs associated with caring for an aging population with chronic diseases are a major concern.1 As the population continues to age, the incidence of diabetes mellitus and other chronic problems are expected to increase. Diabetes prevalence is projected to rise to 21% to 28% of the general US population by 2050, up from 14% of the general US population in 2010.2 Up to one-third of patients admitted to the nursing home (NH) have a diabetes diagnosis, and the costs associated with caring for diabetes in the aging US population could exceed future spending estimates for the entire Medicare program.2,3 The economic costs and human suffering caused by diabetes to individuals, families, communities, and the nation is staggering.1,2 Because of the increase in older Americans with diabetes, this disease has the potential to impact long-term care (LTC) organizations and the sustainability of the US Medicare program, making diabetes prevention and management essential.

In the elderly, diabetes care is particularly challenging because there is much heterogeneity in this population due to differences in length of disease, comorbidities, treatments, and overall health.4 As a systemic illness, diabetes causes long-term macrovascular and microvascular complications, including coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, stroke, retinopathy, gastroparesis, and renal disease. It is the leading cause of new cases of end-stage renal failure and blindness in adults with diabetes-related peripheral vascular disease, and diabetic neuropathy is the leading cause of hospitalizations for foot ulcers and nontraumatic amputations.3 Elderly people may also experience short-term and nontraditional complications of diabetes, such as falls, dehydration, infections, adverse medication effects, cognitive dysfunction, depression, urinary incontinence, and pain syndromes, all of which can reduce quality of life and increase the risk of poor health outcomes.3,5

Residents admitted to NHs often have diabetes in the presence of one or more acute problems, such as stroke, congestive heart failure, pulmonary diseases, end-stage renal disease, infections, and fractures.6 To improve outcomes, current evidence supports an interdisciplinary team approach to managing these conditions in this complex patient population.7-10 As a member of the healthcare team, nurse practitioners (NPs) have demonstrated a role in improving patient outcomes among individuals with chronic diseases by coordinating care through disease management programs.9-16 The Joslin Diabetes Center, which is considered the world’s largest diabetes research center, diabetes clinic, and provider of diabetes education, reported improved diabetes care through the use of NP diabetes care coordinators.16

In this article, we present the results of a quality improvement (QI) project that we undertook to improve diabetes care at our NH facility, which houses both short- and long-stay residents. The project used an NP to lead the diabetes care team, provide diabetes care training to nursing staff, and to manage interdisciplinary diabetes care at the facility within the coordinated diabetes disease management (CDDM) model. We selected the AMDA – The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine (formerly the American Medical Directors Association) diabetes guidelines3 for clinical decision-making, as they provide evidence-based, patient-centered strategies and treatments that consider patient condition, preferences, and function, enabling us to provide personalized care.

Our Diabetes Quality Improvement Project

Our 6-month QI project, which used a single-site repeated measures design, was implemented in a commercially owned, 112-bed LTC and skilled care NH located in South Texas in a county designated as partially medically underserved. Study approval was obtained from the University of Missouri – Kansas City’s Social Science Institutional Review Board with a waiver of consent, as all care provided during the study was in compliance with the current standard of care for diabetes in the NH population. No experimental procedures or care were implemented, and no potential risks to the patients were identified, negating the need for consent; however, all patients agreed to treatment by the NP as a member of the healthcare team. In compliance with Texas regulations, delegation agreements for diagnosis and prescriptive authority were secured for all attending physicians. In addition, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations were followed to protect participants’ health information.

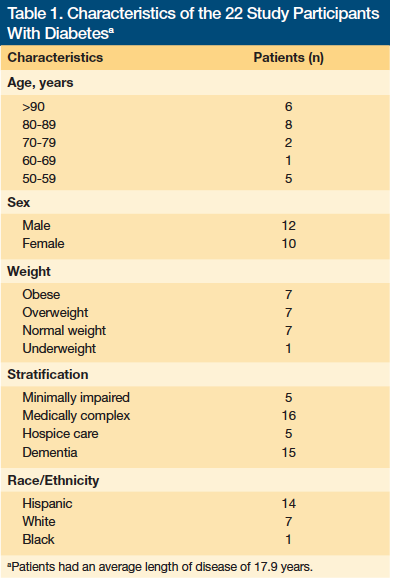

The first step of the QI project required a medical chart review to identify residents with diabetes, including those admitted for short-term healing and rehabilitation and those who were long-stay residents. Of the 88 charts reviewed at the start of the study period in May 2012, 31 (35.23%) included residents with type 2 diabetes mellitus; however, attrition from discharge (n=7) and death (n=2) left a final study population of 22 residents. The NP collected preintervention data for these residents by chart review, which included demographics, resident condition, current treatments, preventive screenings, glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, incidence of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia, patient participation in planning care, and medication use. The demographics and distribution of these individuals are outlined in Table 1.

Following this initial data collection, the QI intervention was implemented using an interdisciplinary team comprised of two physicians and an NP, a director of nursing, an administrator, a staff nurse, a dietician, a pharmacist, an activity director, and a physical therapist. The NP conducted 1-hour training sessions for all nursing staff, including nine licensed vocational nurses, four registered nurses, 14 nursing assistants, and six medication aides. Information about current guidelines for diabetes management, diabetes medications, prevention of diabetes complications, and patient assessments was provided within the context of the geriatric NH population. During these training sessions, information about staff perceptions of problems with diabetes care and suggestions for improving processes related to such care were elicited. After the staff and provider training was completed, implementation of evidence-based care using the AMDA clinical practice guidelines within the CDDM model (Figure) began.

The CDDM process begins with the specialized NP providing information about the patient’s condition and treatment options to the patient, his or her family, and/or caregiver. These individuals are then encouraged to communicate their perceptions and care preferences to the NP. The NP and the patient and his or her family/caregiver then collaborate to establish diabetes outcome goals and formulate an evidence-based plan of care, which is implemented using an interprofessional team approach. The NP is responsible for coordinating care, communication, and referrals among the interprofessional team. The CDDM is a cyclical approach, with patient outcomes periodically evaluated and the NP providing feedback and information to the patient and his or her family/caregiver.

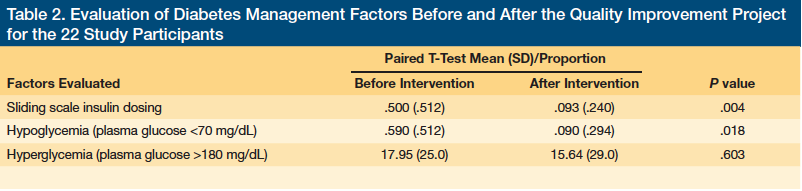

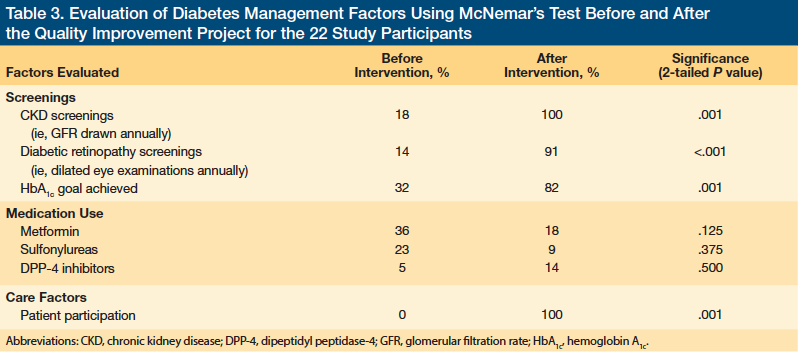

Six months after implementation of the CDDM model, postintervention data were collected for the same variables as preintervention, and paired statistical analyses of the data were conducted. These analyses compared pre- and postintervention demographics, resident condition, sliding scale insulin (SSI) use, incidence of hypoglycemia, incidence of hyperglycemia, use of oral medications (ie, metformin, sulfonylureas, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 [DPP-4] inhibitors), preventive screening for diabetic retinopathy using dilated eye examinations, and staging of chronic kidney disease (CKD) by glomerular filtration rate (GFR). The means for pre- and postintervention SSI use, hypoglycemia, and hyperglycemia (plasma glucose >180 mg/dL) were compared using paired T-tests, with a separate analysis for each item, whereas McNemar’s tests were performed to compare CKD screenings, presence of diabetic retinopathy, attainment of glycemic control, patient participation in planning care, and the use of oral diabetes medications (ie, metformin, sulfonylureas, DPP-4 inhibitors).

Our Findings

We observed that nurse training followed by implementation of evidence-based care using the AMDA clinical practice guidelines within the CDDM model led to significant improvements in patient outcomes, including improvements in attaining HbA1c goals, reductions in hypoglycemia incidence, and decreased use of SSI orders (Table 2). HbA1c laboratory values meeting the individualized goal increased from 36% to 85%. Hypoglycemia incidence decreased from 13 occurrences preintervention to zero occurrences during the last 2 months of the 6-month study period. The use of SSI orders was reduced from 61.29% of patients to 29.41% of patients postintervention. We also found increased resident-centered care, improved CKD staging, and improved diabetic retinopathy screenings (Table 3). The process of insulin medication order entry was changed, which led to improvement in the way capillary glucose measures were documented by nurses, making the data more easily accessible to practitioners at the point of care.

Study Limitations

Our QI project was conducted at a single site and had a small sample size, limiting the generalizability of the results. The implementation of a comprehensive QI project does not facilitate controlled studies as a part of the design. Because of the lack of controls, the impact of history effects (ie, change in condition that may have occurred between the first data collection and the second data collection) cannot be accurately reflected in the study results. In addition, quality of life measures were not evaluated but are important considerations for future research.

Discussion

Patient outcomes and process outcomes were improved through the implementation of the AMDA evidence-based guidelines within the CDDM model. The AMDA guidelines were selected for the QI project because they provide population-specific, patient-centered disease management strategies based on the recommendations of an expert interdisciplinary working group that reviewed the current evidence and recommendations from professional organizations such as the American Diabetes Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.3 Although the AMDA guidelines are widely available to NH practitioners, NHs have reported limited application of these guidelines in the NH population.7 A reason cited for this by primary care practitioners in the NH setting has been time constraints.7

We found that use of a single practitioner with a diabetes focus to manage and coordinate diabetes care facilitated implementation of evidence-based guidelines in a facility where guidelines were not previously implemented. As a healthcare provider, the NP was able to bill for time spent managing and teaching patients about diabetes, enabling the physicians to prioritize their time towards more pressing medical problems. Additionally, improving care processes and reducing the SSI administration time burden on nursing staff led to positive feedback to the team. The nursing team reported that they spent more time caring for the residents’ needs, rather than on “finger sticks,” and also had time to take a break at lunch, which was previously spent hunting down glucose values or administering SSI.

Hypoglycemia (plasma glucose <70 mg/dL) is the most serious adverse drug effect associated with diabetes medications and can result in permanent disability, decreased quality of life, poor health outcomes, increased costs, and death.17,18 Our QI project identified an increased incidence of hypoglycemia in our NH patients, along with a high prevalence of SSI regimens. These findings are not unusual, as treatment plans for elderly NH residents with diabetes often include dangerous medications aimed at lowering blood glucose levels, increasing the risk of adverse drug effects, including hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia.19

Following the QI intervention, the incidence of hypoglycemia was significantly reduced, which was attributed to the significant reduction in the use of SSI regimens and decreased use of sulfonylurea-based medications during the study period; both SSI regimens and use of sulfonylureas have been associated with an increased risk of hypoglycemia.20 In addition, SSI regimens appear on the American Geriatrics Society’s updated Beers criteria as inappropriate for older adults, and the criteria strongly recommend against their use because of the increased risk of hypoglycemia.21 In older patients, hypoglycemia risk increases when SSI regimens are used as long-term monotherapy.3,22 Current evidence supports eliminating SSI regimens for nonacute patients because of the lack of evidence documenting their effectiveness and the increased risks for hypoglycemia, prolonged periods of hyperglycemia, and medication errors.22

The use of metformin and sulfonylureas (both glyburide and glipizide) also decreased over the study period. Of note, two sulfonylureas, glyburide and the older drug, chlorpropamide, appear on the Beers list of medications to avoid in the elderly due to an increased risk for prolonged periods of hypoglycemia.21 In contrast, glipizide has demonstrated less hypoglycemia risk, does not depend on the kidneys for elimination, and may be useful in the older NH population with multiple comorbidities.3 DPP-4s, such as sitagliptin, are useful as a first-line therapy or when there is poor glycemic control on metformin and sulfonylureas.3 DPP-4s are generally well-tolerated in the NH population, but the cost of these medications may be a limiting factor in their use.

Although hypoglycemia incidence improved over the study period, the incidence of hyperglycemia remained stable and continued to be a persistent problem. Treating hyperglycemia effectively is important for the prevention of short-term problems, such as infections, falls, dehydration, urinary incontinence, and pain.3 The persistence of hyperglycemia during our study may be related to ineffective insulin coverage for carbohydrate intake, an overly conservative approach to treatment of hyperglycemia, steroid use, and advanced disease in our study population, all of which are factors that have been associated with hyperglycemia.23 Mealtime insulin dosing was prescribed in two parts. The first part was a fixed dose of insulin aimed at covering the carbohydrates consumed during the meal; however, establishing an effective insulin dose for mealtime carbohydrate intake may be challenging in this population because of inconsistent eating patterns.3 The second part was a correction dose of rapid-acting insulin added to the fixed mealtime dose to treat preprandial hyperglycemia.

Despite hyperglycemia remaining persistent, several care processes were improved during our study, including the staging of kidney function by GFR calculation. Knowledge of kidney function in people with diabetes is important for monitoring and evaluating renal complications and for medical decision-making. Prior to the intervention, the laboratory serving our NH did not include a GFR calculation on the metabolic panel results. During the QI study, inclusion of the GFR calculation results on the medical record increased to 100% compliance. As a result, diagnosis and staging for CKD was realized for eight patients who did not have a previous CKD diagnosis. Because of the risk for lactic acidosis in people with CKD using metformin, the drug was discontinued in four patients, reducing their risk of complications.24

The number of HbA1c laboratory values that were recorded in the medical record also improved significantly over the course of the study period. HbA1c levels were available for 12 patients (55%) preintervention and increased to 100% postintervention. At the end of the study, 82% of patients had met their HbA1c goal, but the significance of this change is unclear because HbA1c levels were only available for a few patients preintervention. HbA1c is useful in understanding glycemic control over an 8- to 12-week period, but has its limitations. In the elderly, factors such as glucose excursions, anemia, renal disease, and age can affect HbA1c levels.25 HbA1c also does not reflect extremes of glucose, including episodes of dangerous hypoglycemia and severe hyperglycemia. Therefore, when evaluating glycemic control, the practitioner must consider HbA1c values along with capillary blood glucose (CBG) measures to get a clear picture of glycemic control. Our intervention improved documentation of CBG values on the medication administration record. Before the intervention, the CBG information was difficult to read and interpret. This information was scattered throughout multiple pages of the printed medical administration record, making it difficult to find and use CBG values. The QI initiative improved the process for managing CBG information by changing the way insulin orders were entered into the pharmacy software. This change resulted in a medical administration record with a single page of glucose values, providing information to the prescriber in an accessible and organized format for use in point-of-care clinical decision-making.

Considerations for Improving Diabetes Care

Patient-centered care is essential to improving diabetes care, and it is a core component of quality healthcare in the Institute of Medicine’s 2010 National Healthcare Disparities Report.26 In patient-centered care, the patient and his/her family receives information about the patient’s condition and treatment options, and they are able to express their preferences to the healthcare practitioner, facilitating an exchange of healthcare information between the patient/family and practitioner. This process of communication facilitates understanding, empathy, and respect for the values and preferences of the individual.26 In addition, when an individual participates in the planning of his/her own care, he/she is more likely to attain his/her individual goals.17 Patient-centeredness is not a new concept. It is at the core of the theory of goal attainment, which was formulated by Imogene King, a pioneer in the development of nursing theory, in the early 1960s, and the concepts are embedded within the CDDM model, providing a theoretical framework for patient-centered interactions.17,27,28 It is important to note that written communication of patient-centered treatment goals among the interprofessional team has been shown to lead to goal attainment and improved health outcomes.25,29

When establishing patient-centered glucose goals, the practitioner must consider the risk of hypoglycemia.3 Elderly NH patients often have cognitive deficits due to dementia and comorbidities and may not be able to recognize or verbalize symptoms of hypoglycemia. This lack of awareness and difficulty with communication can result in unreported and more severe episodes of hypoglycemia.30 The risks for hypoglycemia in the elderly is the rationale for current recommendations for more liberalized HbA1c goals (<8.0%), while HbA1c goals for the community-dwelling population remain lower (<6.5% or <7%).3,31,32 However, setting more liberalized glucose goals may not prevent hypoglycemia in these individuals, as the incidence of hypoglycemia has been found to increase in elderly people with overall poorer glucose control.31

At the same time, the benefits of tight glucose control to prevent vascular complications may not be ideal for the elderly NH population with a limited life expectancy.4,31 In these cases, goals may be more appropriately aimed at prevention of short-term complications and improved quality of life.16 In contrast, tighter glucose control may be appropriate for individuals admitted to an NH for short-term, rehabilitative stays, as this may promote healing and prevent vascular complications.

The use of oral medications in the NH should be individualized due to differences in comorbidities. Practitioners must consider conditions such as kidney disease, liver disease, edema, gastrointestinal problems, and heart failure when selecting oral medications.3 For this reason, the AMDA clinical practice guidelines do not recommend specific algorithms for the use of oral diabetes medications in the NH patient. Instead, they encourage practitioners to consider glycemic control goals, patient condition, and cost.3 For example, metformin is considered first-line therapy for diabetes management, but this medication may not be appropriate for older NH residents because of the risk for lactic acidosis in severe CKD and gastrointestinal problems.3,33

Finally, quality of life is an important consideration when establishing outcome goals for the NH population.16 Intensive diabetes treatments, such as multiple daily insulin injections, may be perceived as having a negative impact on quality of life.34 Differences in patient perceptions about treatment plans and their impact on quality of life is another reason why shared treatment decision-making between patient and practitioner is imperative.34

Conclusion

NH residents with diabetes represent a heterogeneous population due to differences in condition, function, life expectancy, and comorbidities, with some admitted for permanent residency and care and others admitted for short-term rehabilitation and healing. Therefore, when managing diabetes in this diverse population, priority should be given to controlling hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, and improving quality of life, which necessitates a patient-centered approach. We found that the CDDM model in combination with AMDA’s diabetes clinical practice guidelines for clinical decision-making provides an effective framework for setting patient-centered goals while facilitating evidence-based care. This pilot used a diabetes-specialized NP to provide disease management and coordinate the interprofessional care team involved in diabetes care. Although the use of a specialized diabetes NP may generate additional billing costs and increase healthcare costs associated with diabetes care, in this pilot the findings were that it improved patient and process outcomes. A comparison of pre- and postintervention data revealed that the pilot model improved glycemic control, decreased the incidence of hypoglycemia, increased resident-centered care, increased the incidence of recommended screenings (when appropriate), and decreased SSI orders, all of which have the propensity to reduce the long-term costs associated with diabetes care. Understanding the costs and savings associated with specialty care and the anticipated improved health outcomes in the areas of hospital readmission, adverse medication effects, infections, wounds, falls, and quality of life are important to the understanding of the value of specialized diabetes care for the NH population. Continued and ongoing monitoring of outcomes related to diabetes care is needed to evaluate and plan for future interventions aimed at further improving diabetes care.

References

1.Akushevich I, Kravchenko J, Ukraintseva S, Abeev K, Yashin AI. Age patterns of incidence of geriatric disease in the U.S. elderly population: Medicare-based analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(2):323-327.

2.Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Gregg EW, Barker LE, Williamson DF. Projection of the year 2050 burden of diabetes in the US adult population: dynamic modeling of incidence, mortality, and prediabetes prevalence. Popul Health Metr. 2010;8:29. www.pophealthmetrics.com/content/8/1/29. Accessed July 2, 2014.

3.Clinical practice guideline: diabetes management in the long-term care setting. AMDA – The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine website. www.amda.com. Published 2011. Accessed June 30, 2014.

4.Huang ES, Zhang Q, Gandra N, Chin MH, Meltzer DO. The effect of comorbid illness and functional status on the expected benefits of intensive glucose control in older patients with type 2 diabetes: a decision analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(1):11-19.

5.Caspersen CJ, Thomas GD, Boseman LA, Beckles GL, Albright AL. Aging, diabetes, and the public health system in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(8):1482-1497.

6.Table 6. Medicare & Medicaid Statistical Supplement: 2011 Edition. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareMedicaidStatSupp/2011.html. Published September 5, 2012. Accessed July 3, 2014.

7.Garcia TJ, Brown SA. Diabetes management in the nursing home: a systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Educ. 2011;37(2):167-187.

8.Huang ES, John P, Munshi MN. Multidisciplinary approach for the treatment of diabetes in the elderly. Aging Health. 2009;5(2):207-216.

9.McAiney CA, Haughton D, Jennings J, Farr D, Hillier L, Morden P. A unique practice model for nurse practitioners in long-term care homes. J Adv Nurs. 2008; 62(5):562-571.

10. Ruben DB, Ganz DA, Roth CP, McCreath HE, Ramirez KD, Wenger NS. Effect of nurse practitioner comanagement on the care of geriatric conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(6):857-867.

11. Bartol T. Improving the treatment experience for patients with type 2 diabetes: role of the nurse practitioner. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2012;24(suppl 1):270-276.

12. Chang K, Davis R, Birt J, Castelluccio P, Woodbridge P, Marrero D. Nurse practitioner-based diabetes care management: impact of telehealth or telephone intervention on glycemic control. Disease Management and Health Outcomes. 2007;15(6):377-385.

13. Conlon PC. Diabetes outcomes in primary care: evaluation of the diabetes nurse practitioner compared to the physician. Primary Healthcare. 2010;20(5):26-31. Accessed July 3, 2014.

14. Robertson C. The role of the nurse practitioner in the diagnosis and early management of type 2 diabetes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2012;24(suppl 1):225-233.

15. Wallymahmed ME, Morgan C, Gill GV, Macfarlane IA. Nurse-led cardiovascular risk factor intervention leads to improvements in cardiovascular risk targets and glycaemic control in people with type 1 diabetes when compared with routine diabetes clinic attendance. Diabet Med. 2011;28(3):373-379.

16. Nudo K, Munshi M, Lekarcyk J. Development and implementation of a clinical program to improve diabetes management in long term care facilities. Paper presented at: AMDA Long Term Care Medicine - 2012; March 12, 2012; San Antonio, TX. www.prolibraries.com/amda/?select=session&sessionID=849. Accessed July 28, 2014.

17. Meneilly G. Pathophysiology of diabetes in the elderly. Clinical Geriatrics. 2010;18(4):25-28. www.consultant360.com/articles/pathophysiology-diabetes-elderly. Accessed July 2, 2014.

18. Alagiakrishnan K, Mereu L. Approach to managing hypoglycemia in elderly patients with diabetes. Postgrad Med. 2010;122(3):129-137.

19. Cayea D, Durso SC. Management of diabetes mellitus in the nursing home. Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging. 2007;15(5):27-33.

20. Salem BC, Fathallah N, Hmouda H, Bouraoui K. Drug-induced hypoglycaemia: an update. Drug Saf. 2011;34(1):21-45.

21. American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

22. Goodwin Z, Kiehl EM, Peterson JZ. King’s theory as foundation for an advance directive decision-making model. Nurs Sci Q. 2002;15(3):237-241.

23. Pandya N, Thompson S, Sambamoorthi U. The prevalence and persistence of sliding scale insulin use among newly admitted elderly nursing home residents with diabetes mellitus. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(9):663-669.

24. Warren RE, Strachan MW, Wild S, McKnight JA. Introducing estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) into clinical practice in the UK: implications for the use of metformin. Diabet Med. 2007;24(5):494-497.

25. Ford ES, Cowie CC, Li C, Handelsman Y, Bloomgarden ZT. Iron-deficiency anemia, non-iron-deficiency anemia and HbA1c among adults in the US. J Diabetes. 2011;3(1):67-73.

26. Future Directions for the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2010. Accessed July 1, 2014.

27. Huang ES, Brown SE, Ewigman BG, Foley EC, Meltzer DO. Patient perceptions of quality of life with diabetes-related complications and treatments. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(10):2478-2483.

28. Munshi MN, Segal AR, Suhl E, et al. Frequent hypoglycemia among elderly patients with poor glycemic control. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):362-364.

29. Khowaja K. Utilization of King’s interacting systems framework and theory of goal attainment with new multidisciplinary model: clinical pathway. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2006;24(2):44-50.

30. American Diabetes Association position statement: standards of medical care in diabetes - 2012. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(suppl 1):S11-S63.

31. Dickerson LM, Ye X, Sack JL, Hueston WJ. Glycemic control in medical inpatients with type 2 diabetes mellitus receiving sliding scale insulin regimens versus routine diabetes medications: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(1):29-35.

32. Sieloff C. Imogene King: A Conceptual Framework for Nursing. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications; 1991.

33. King IM. A theory of goal attainment: philosophical and ethical implications. Nurs Sci Q. 1990;12(4):282-286.

34. McNabney MK, Panya N, Iwuagwu C, et al. Differences in diabetes management of nursing home patients based on functional and cognitive status. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005;6(6):375-382.

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to: Cristi L. Day, DNP, RN, Assistant Professor, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, 6300 Ocean Drive, Island Hall 344, Corpus Christi, TX 78412; cristi.day@tamucc.edu

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to acknowledge Coastal Palms Nursing Center, Charles Gregory, DO, and Jerome A. LeeSang, MD, for their contributions to the success of this quality improvement project.