Improved Renal and Cognitive Function in a Hospice Patient After Polypharmacy Reduction

Affiliations:

1Department of Family Medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA

2Department of Physiological Sciences, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA

Abstract: Older adults presenting with unexplained decline in renal and cognitive function should be evaluated for polypharmacy as a potential cause. The authors report the case of a patient admitted to hospice for end-stage renal disease, progressive dementia, and failure to thrive. After stopping and/or reducing the dose of eight different medications, she showed dramatic improvements in her glomerular filtration rate, cognition, functional status, and weight, leading to her discharge from hospice care. Although none of her medications were known to be nephrotoxic, she had been taking several medications at doses higher than those recommended for her degree of renal impairment. She was also receiving several inappropriate medications per the American Geriatrics Society’s Updated Beers criteria. This case highlights the positive impact that careful medication reviews and adjustments can have in elderly patients with renal impairment, including trials of stopping potentially unnecessary and inappropriate medications.

Key words: Alzheimer’s disease, Beers criteria, dementia, famotidine, frailty, hospice, memantine, polypharmacy, renal impairment, renal toxicity, somnolence, weight loss.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Taking multiple drugs without an appropriate indication and polypharmacy, which can be broadly defined as taking a large number of pharmaceutical drugs (generally >4 medications), are significant sources of morbidity and mortality in the older patient population.1,2 An increase in the number of drugs a patient takes has been associated with a greater incidence of medication-related adverse effects.3-8 The risk of adverse effects has been reported to be 15% with two medications, 58% with five medications, and 82% with seven or more medications.8 On average, nursing home residents take seven medications daily9; thus, it is not surprising that these individuals are at extremely high risk of polypharmacy-related comorbidities and poor health outcomes.

Older individuals also have diminished physiologic reserve as a result of alterations in pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, increasing their likelihood of comorbidities upon improper medication use. Beers and associates10 recognized this risk when conducting their landmark survey in 1991, which delineated inappropriate medications that were commonly being prescribed to elderly persons. The authors made a special note of drug classes that could exacerbate delirium and dementia, such as sedatives, anticholinergics, and H2 receptor antagonists. They warned that use of these medications in susceptible patients could exacerbate coexisting morbidities and quickly deteriorate their health status, or lead to inaccurate medical diagnoses or prognostications. The American Geriatrics Society updated the Beers criteria in 2012,11 and they remain an important resource for preventing inappropriate prescribing in elderly persons.

We report the case of a patient on a polypharmacy regimen who had severe renal impairment, was not considered a candidate for dialysis, had a disability level of stage 7a (ie, severe dementia with verbal ability limited to <10 words on an average day and full assistance needed for walking, bathing, dressing, toileting, and eating12) on a Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST), and had anorexia and weight loss, all of which culminated in her admission to hospice care. While in hospice, she underwent polypharmacy reduction and was discharged 6 months later due to significant improvements in each of these health parameters, indicating the importance of conducting thorough medication reviews for all elderly persons.

Case Report

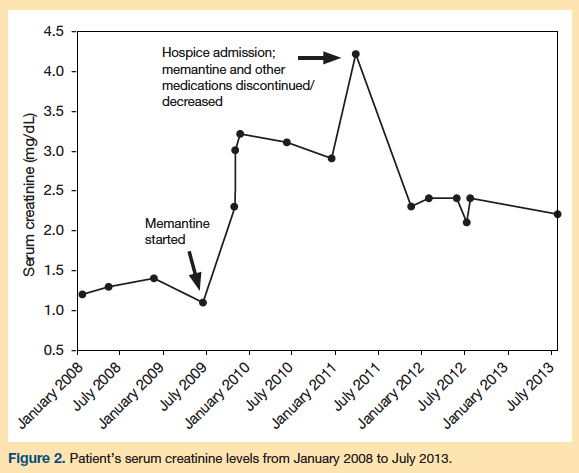

A 93-year-old female nursing home resident was enrolled in hospice after developing stage 5 chronic kidney disease, with a serum creatinine level of 4.2 mg/dL (normal, 0.6-1.2 mg/dL) and a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 10 mL/min/1.73 m2 (normal, >90 mL/min/1.73 m2). She was not considered a candidate for dialysis due to several comorbidities. She also had progressive dementia with a FAST score of 7a, failure to thrive, and a weight loss of 18 lb over the preceding 6 months, leaving her with a body mass index (BMI) of 19 kg/m2. She was oriented to name only, with a score of 0/3 for 3-minute recall on the Mini-Cog assessment, and she would not attempt the clock-drawing test. She had associated behavioral difficulties with long periods of somnolence interspersed with occasional outbursts of verbal and physical aggression toward staff. She had a history of lacunar stroke and vascular dementia with extensive small vessel ischemia shown on computed tomography (CT) scan in 2009. Before enrolling in hospice, the patient experienced frequent falls (approximately two per month). Other diagnoses for which she was being treated included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)/asthma, hypertension, hypothyroidism, gastroesophageal reflux disease, macular degeneration, anxiety/depression, coronary artery disease, and pain for a rib fracture.

Her medications prior to hospice admission are listed in the Table. After admission to hospice, a medication review was conducted, and memantine and donepezil were stopped due to a perceived lack of benefit. Following this change in her regimen, we noted mild improvement in her functional status. Zolpidem was also stopped due to falls and confusion, but the patient continued to receive alprazolam twice daily and as needed due to her episodes of combativeness. Several months into hospice, her new attending physician conducted a second medication review and made additional changes as follows:

1. Decreased famotidine from 20 mg twice daily to 10 mg once daily. This change was made because the revised dose is recommended for a GFR above 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, and because H2 blockers in high doses have been associated with increased confusion in elderly persons.13

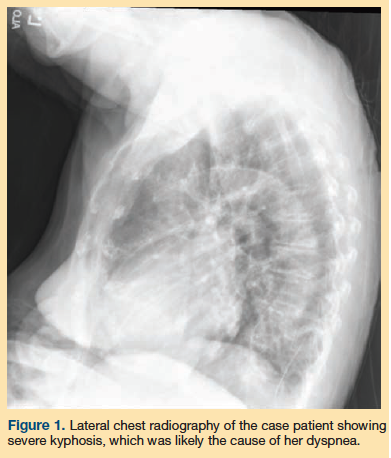

2. Stopped fluticasone/salmeterol due to lack of documented COPD. The patient had no history of smoking and had no respiratory symptoms other than an occasional cough and dyspnea upon exertion. Fluticasone/salmeterol had been started 2 years earlier after the patient experienced an episode of pneumonia. Pulmonary function testing records were not available; however, she had marked kyphosis (Figure 1), which was suspected to be the cause of her dyspnea. In the literature, kyphosis has been associated with deconditioning and restrictive lung disease.14

3. Stopped montelukast due to a lack of documented asthma and because there have been reports concerning the neuropsychiatric side effects of this medication. Such reports resulted in a 2009 US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warning about the use of this medication.15

4. Decreased mirtazapine from 15 mg daily at bedtime to 7.5 mg daily at bedtime for improving appetite stimulation. This change was made to conform to the dose recommendation for the patient’s documented GFR, and to avoid the sedation that has been noted to occur with mirtazapine at higher doses, particularly among those with impaired renal function.16

5. Decreased alprazolam to every 12 hours as needed for her agitation. After a gradual period of tapering, the medication was only used approximately once every 2 weeks, and it has since been discontinued.

Following these medication changes, the patient’s mental status and appetite gradually improved over the next 2 months. She gained 10 lb and was able to walk longer distances with fewer falls. Laboratory testing was repeated and showed a reduction in serum creatinine levels to 2.3 mg/dL and an increase in GFR to 21 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Figure 2). The patient was also found to be much more verbal and coherent, and she was able to participate in most group activities. Due to her marked improvement in renal function, cognition, and functional status, she was subsequently discharged from hospice.

The patient still resides at the nursing home more than 2 years following her discharge from hospice care, and she has had no falls in the past 6 months. Her GFR of 21 mL/min/1.73 m2 has remained stable, and her Mini-Cog assessment has considerably improved. Her latest test revealed a score of 2/3 on 3-minute recall and she drew an almost accurate clock on the clock-drawing component; the only exception was the spacing of some numbers on the clock, which was attributed to the patient’s macular degeneration. Her appetite has also been good, enabling her to maintain a stable weight of about 18 lb above her low (BMI of 23 kg/m2 vs previous low of 19 kg/m2).

Discussion

This case illustrates the importance of evaluating and adjusting medication doses in elderly patients with renal disease. This is especially important for medications requiring renal dose adjustments due to their potential central nervous system side effects. In our patient, medications requiring renal adjustments included the following: (1) famotidine, to mitigate the risk of confusion and anxiety13; (2) memantine, to reduce the risk of somnolence and hallucinations17; and (3) mirtazapine, to prevent sedation.16 She had been taking both memantine and famotidine at doses above those recommended for her degree of renal impairment. We suspect that famotidine was a significant factor in our patient’s somnolence, though multiple other medications could have contributed (Table).

In 2001, the FDA issued a warning about increased drowsiness in elderly persons on famotidine with even moderate renal insufficiency (GFR <50 mL/min/1.73 m2).18 We also discontinued zolpidem and alprazolam, which are on the Beers list of medications associated with increased confusion and falls in the elderly,11 and renally adjusted the mirtazapine dose, as it has sedation as a common side effect.

It is important to periodically reevaluate indications for all medications, even in cases where the drug(s) are not renally metabolized. If there is no strong indication for a given medication, a trial of tapering or discontinuation can help discern the presence of side effects and determine whether the medication was actually necessary. In our patient, the diagnoses of COPD and asthma appeared questionable, and the possibility of side effects from her fluticasone/salmeterol (anxiety) and montelukast (potential neuropsychiatric side effects15) led to a successful trial of discontinuation without development of respiratory symptoms.

Although our patient’s cognitive impairment was thought to be due to Alzheimer’s disease, the improvement and subsequent stabilization of her cognition after memantine and donepezil were discontinued makes this diagnosis unlikely. Instead, a diagnosis of mild vascular dementia is more likely based on her history of stroke and other CT findings, her relatively preserved short-term memory 5 years after her dementia diagnosis, and minimal progression of cognitive impairment after dementia onset. In addition, donepezil has been associated with anorexia and other gastrointestinal symptoms in elderly persons19 and may have been a factor in our patient’s poor appetite and weight loss.

It is difficult to determine the precise reason for our patient’s improvement in renal function, as none of her medications have been implicated as having a causative effect on renal failure, with the possible exception of memantine. Some postmarketing surveillance studies of memantine have reported renal toxicity.17 Recent evidence suggests that the cumulative burden of multiple medications is associated with increased risk of renal failure in the elderly population, even if none of the medications are specifically nephrotoxic.20 This thought expands on the previously known benefits of reducing polypharmacy in the elderly population, and is especially true for persons with unexplained decline in renal function and cognition, particularly when hospice care is being considered.

Conclusion

Reducing polypharmacy has many proven benefits in the elderly. Our report suggests that reversing renal failure in the context of dementia and failure to thrive by reducing the cumulative burden of multiple medications may be yet another benefit. Particular attention should be paid to dose adjustment or discontinuation of renally metabolized medications in this population, including memantine and famotidine.

References

1. Hovstadius B, Petersson G. Factors leading to excessive polypharmacy. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):159-172.

2. Shah BM, Hajjar ER. Polypharmacy, adverse drug reactions, and geriatric syndromes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):173-186.

3. Bjerrum L, Søgaard J, Hallas J, Kragstrup J. Polypharmacy: correlations with sex, age and drug regimen. A prescription database study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54(3):197-202.

4. Edelman EJ, Gordon KS, Glover J, McNicholl IR, Fiellin DA, Justice AC. The next therapeutic challenge in HIV: polypharmacy. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(8):613-628.

5. Hajjar ER, Cafiero AC, Hanlon JT. Polypharmacy in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5(4):345-351.

6. Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):989-995.

7. Steinman MA, Landefeld CS, Rosenthal GE, Berthenthal D, Sen S, Kaboli PJ. Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(10):1516-1523.

8. Bland CM. Polypharmacy and the elderly. Presented at: 2013 American College of Physicians Georgia Chapter Scientific Meeting; October 4-6, 2013; Savannah, GA. www.acponline.org/about_acp/chapters/ga/13-bland.pdf. Accessed July 11, 2014.

9. Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG, Kouladjian L, Hilmer SN. Deprescribing trials: methods to reduce polypharmacy and the impact on prescribing and clinical outcomes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28:237-253.

10. Beers MH, Ouslander JG, Rollingher I, Reuben DB, Brooks J, Beck JC. Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. UCLA Division of Geriatric Medicine. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(9):1825-1832.

11. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631. www.americangeriatrics.org. Accessed July 11, 2014.

12. Reisberg B, Franssen EH, Souren LE, Auer S, Kenowsky S. Progression of Alzheimer’s disease: variability and consistency: ontogenic models, their applicability and relevance. Neural Transm Suppl. 1998;54:9-20.

13. Henann NE, Carpenter DU, Janda SM. Famotidine-associated mental confusion in elderly patients. Drug Intell Clin Pharm.1988;22(12):976-978.

14. Harrison RA, Siminoski K, Vethanayagam D, Majumdar SR. Osteoporosis-related kyphosis and impairments in pulmonary function: a systematic review. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(3):447-457.

15. Postmarket Drug Safety Information for Patients and Providers: Updated Information on Leukotriene Inhibitors: Montelukast (marketed as Singulair), Zafirlukast (marketed as Accolate), and Zileuton (marketed as Zyflo and Zyflo CR). US Food and Drug Administration website. https://1.usa.gov/1nFmNcn. Updated August 28, 2009. Accessed May 30, 2014.

16. RemeronSolTab (mirtazapine) [prescribing information]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co., Inc. www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/r/remeron_soltab/remeron_soltab_pi.pdf. Accessed July 11, 2014.

17. Namenda (memantine HCl) [prescribing information]. St Louis, MO: Forest Laboratories, Inc. Updated October 2013. Accessed May 30, 2014.

18. Pepcid (famotidine) [prescribing information]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. https://1.usa.gov/1r9Fhrm. Updated November 2013.

Accessed July 11, 2014.

19. Aricept (donepezil) [prescribing information]. Woodcliff Lake, NJ: Eisai Inc. www.aricept.com/docs/pdf/aricept_PI.pdf. Updated August 2013. Accessed July 11, 2014.

20. Chang YP, Huang SK, Tao P, Chien CW. A population-based study on the association between acute renal failure (ARF) and the duration of polypharmacy. BMC Nephrology. 2012;13:96.

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to: Richard Whalen, MD, Eastern Virginia Medical School, 825 Fairfax Avenue, Hofheimer Hall, Suite 118, Norfolk, VA 23507; WhalenRM@evms.edu