Implications of Recent Drug Approvals for Older Adults

More than 100 medications were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as new drugs or for new indications in 2014 and 2015. Several of the new drugs may benefit older adults, but adverse events and pharmacokinetic changes due to aging must be considered. This article will focus on three recently approved drugs that are marketed for chronic conditions that can affect older adults: suvorexant, for treatment of insomnia; edoxaban, for prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular atrial brillation and for treatment of venous thromboembolism; and droxidopa, for treatment of symptomatic neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. Information about indications, mechanisms of action, dosing, efficacy, and safety are reviewed. The place of each agent in therapy for older adults is also discussed.

Key words: older adults, new drug approvals, suvorexant, edoxaban, droxidopa

More than 70 medications were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as new drugs or for new indications in 2014, and there were more than 50 approvals in 2015.1 Several of these new drugs may benefit older adults, but clinicians must consider adverse events and pharmacokinetic changes due to aging. In addition, older adult participants in the clinical trials necessary for drug approval are often healthier and younger than those who are prescribed medications in practice.2 Therefore, it is important to consider age limitations in trials as well as differences in safety and efficacy in older versus younger age groups. In particular, overall trial demographics should be evaluated to determine if new medications have been studied in older adults with renal or hepatic impairment and common comorbidities.

This article will review the efficacy, safety, cost, and place in therapy for three drugs approved in 2014–15, as presented at the 2015 Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Geriatrics Society (May 15–17; Washington, DC).

Suvorexant

Suvorexant is a novel orexin receptor antagonist approved for the treatment of primary insomnia that improves both sleep onset and maintenance.3 The orexin neuropeptide signaling system supports wakefulness, and suvorexant blocks the binding of orexin neuropeptides to receptors, thus suppressing the wake drive. Initial dosing of oral suvorexant is 10 mg daily, with a maximum approved dose of 20 mg daily. For older adults, there are no dosage adjustments for renal impairment or advanced age.3 Suvorexant is scheduled as a controlled substance (C-IV)4 because adverse effects, such as amnesia and problems performing sleep-related activities (eg, walking, eating, driving), may be similar to those found in zolpidem.3 The estimated average wholesale price (AWP) of suvorexant is $316 for a 30-day supply of 10-mg, 15-mg, or 20-mg tablets.5

Efficacy and Safety

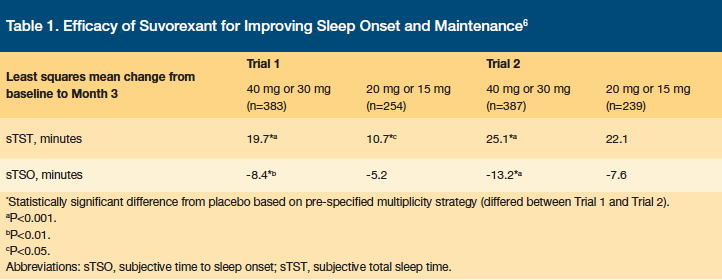

Suvorexant has been studied versus placebo in two randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, phase 3 trials whose primary objective was to evaluate the efficacy of suvorexant over 3 months, based on subjective information from patients’ sleep diaries: subjective total sleep time (sTST), subjective time to sleep onset (sTSO), wakefulness after persistent sleep onset (WASO), and latency to onset of persistent sleep (LPS).6 There were 1021 patients enrolled in the first trial and 1009 patients in the second trial, and the average patient in each trial was 55–57 years of age, female, normal weight, white, and had a baseline sTST of 298–322 minutes and a baseline sTSO of 63–86 minutes. Patients were randomized to receive suvorexant 40 mg or 20 mg daily if they were younger than 65 years of age, or suvorexant 30 mg or 15 mg daily if they were 65 years or older. Patients receiving suvorexant in the study gained 10.7–22.1 more minutes of sleep per night and fell asleep 5.2–7.6 minutes faster than patients receiving placebo.6 Results for sTST and sTSO are shown in Table 1. Although improvements in sTST and sTSO were statistically significant versus placebo, the clinical significance of these improvements to the individual patient should be considered.

A 2014 study by Michelson and colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of suvorexant over 1 year.7 The average patient in this study was 61–62 years old, female, overweight, and white.7 Patients were randomized to receive suvorexant 30 mg daily if 65 years of age or older or 40 mg daily if younger than 65 years of age.7 Eleven percent of patients in the suvorexant group discontinued due to adverse events, and a total of 63% of participants completed 1 year of the study. The most prevalent adverse event was mild-to-moderate somnolence (4% vs 1% with placebo), which was also the most common reason for discontinuation.7 Somnolence occurred most frequently during the first 3 months of the study (11% with suvorexant vs 2% with placebo) and decreased in incidence as the study went on (3% with suvorexant vs less than 1% with placebo). Other common adverse events were fatigue and dry mouth (6.5% and 5.0% with suvorexant, respectively, vs 1.9% and 1.6% with placebo, respectively).7

At the end of 1 year, patients who received suvorexant were randomized to a 2-month discontinuation trial.7 No significant differences in the incidence of rebound insomnia and withdrawal effects were observed between patients who continued suvorexant (n=152) and those who abruptly discontinued (n=161).7 Thus, this study demonstrated tolerability over 1 year, as well as safety of abrupt discontinuation with high doses of suvorexant.

In terms of efficacy, improvement in sTST from Month 1 to Month 12 with suvorexant (from 16.2 minutes to 30.5 minutes) was significantly greater than with placebo (from 16.2 minutes to 38.8 minutes).

Place in Therapy

Prescribing information for suvorexant states that 829 patients in clinical trials of the drug were 65 years of age or older, and 159 patients were 75 years or older.3 The manufacturer reports that there were no significant differences in safety and efficacy for older patients versus younger patients,3 even considering the administration of high doses in several studies. However, a small study in healthy older adults awakened during the night suggested that their balance might be impaired.3 In addition, patients who are female and/or obese may be exposed to higher levels of suvorexant and therefore be more susceptible to its effects. Use of suvorexant is contraindicated for patients with a history of narcolepsy, due to antagonism of orexin receptors by the drug.3 Adverse effects can be potentiated by concomitant use of central nervous system (CNS) depressants.3,5

Suvorexant has not been studied in patients with a history of obstructive sleep apnea, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, substance abuse, certain neurologic disorders (including cognitive impairment), or major psychiatric illness.3 At this time, no published studies directly compare suvorexant to other agents that are approved by the FDA for the treatment of insomnia, including eszopiclone, zaleplon, zolpidem (both immediate- and controlled-release), temazepam (short-term use), and ramelteon (sleep onset only). Suvorexant has also not been compared to the non–FDA approved agent melatonin, which is used to reduce sleep-onset latency. Thus, comparative effectiveness research is needed.

The American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update warns against the use of both benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine hypnotics for insomnia because of increased risk of cognitive impairment, delirium, falls and fractures, and motor vehicle accidents.8 In addition, there may be minimal improvement in insomnia with non-benzodiazepine hypnotics.8 Although suvorexant is approved for the treatment of primary insomnia, the drug should be avoided for the treatment of insomnia in older adults based on the limited efficacy of suvorexant in clinical trials and the similarity of its adverse event profile to benzodiazepine and non-benzodiazepine hypnotics. Non-pharmacological strategies such as sleep hygiene and structured cognitive behavioral therapies for insomnia remain first-line treatments for chronic insomnia.9

Edoxaban

Edoxaban is a factor Xa inhibitor approved for: 1) the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism (SE) in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF); and 2) the treatment of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) after 5–10 days of a parenteral anticoagulant.10 Edoxaban selectively inhibits free factor Xa and prothrombinase activity, thereby preventing thrombin-induced platelet aggregation.10 Dosing is based on indication and creatinine clearance (CrCl). Blister-pack dispensing may be helpful for older adults who are managing their own medications and have multiple medications or mild cognitive impairment. The estimated AWP of edoxaban is $332 for a 30-day supply of each 15-mg, 30-mg, or 60-mg tablets.11

The normal dosing of edoxaban for patients with NVAF is 60 mg daily with or without food, and there are no dosage adjustments for advanced age.10 Results from the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 (Effective aNticoaGulation with factor xA next GEneration in Atrial Fibrillation–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48) trial demonstrated an increased risk of ischemic stroke versus warfarin in patients with a CrCl (according to the Cockcroft-Gault equation) >95 mL/min; edoxaban should not be prescribed to such patients in practice.10 In addition, edoxaban should be adjusted to 30 mg daily if CrCl is 15–50 mL/min.10 Clinicians should be aware that patients with a CrCl <30 mL/min were excluded from the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 study.

The normal dosing for patients with DVT or PE is 60 mg daily with or without food, initiated after 5–10 days of a parenteral anticoagulant.10 The dose is reduced to 30 mg daily if patients have a CrCl of 15–50 mL/min, a body weight of 60 kg or less, or are taking a concomitant P-gp inhibitor. It should be noted that patients with a CrCl <30 mL/min were excluded from the Hokusai-Venuous thromboembolism (VTE) trial. There are no dosage adjustments for advanced age.10

Efficacy and Safety

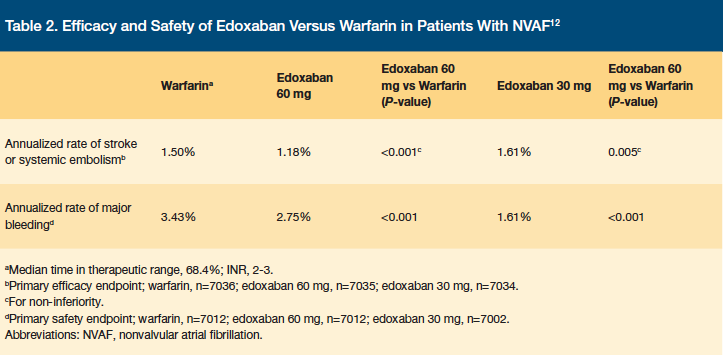

The ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 study was a double-blind, double-dummy, noninferiority trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of edoxaban in NVAF.12 Patients were randomized to receive edoxaban 60 mg daily, 30 mg daily, or warfarin.12 Patients with a CrCl of 30–50 mL/min, a weight of 60 kg or less, and/or taking concomitant verapamil or quinidine received 30 mg daily, and patients with a CrCl of less than 30 mL/min, high risk of bleeding, dual antiplatelet therapy, or moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis were excluded. The primary endpoints of the study were time to first stroke or SE and major bleeding. A total of 21,105 patients were enrolled in the trial with a median follow-up time of 2.8 years. The average patient was 72 years of age, male, and had a Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age ≥75 years, Diabetes mellitus, Stroke or TIA symptoms previously (CHADS2) score of 3 or greater.12 The trial showed that edoxaban was noninferior to warfarin for the prevention of stroke and that major bleeding rates were decreased in patients with NVAF.12 Results for the primary endpoints are shown in Table 2.

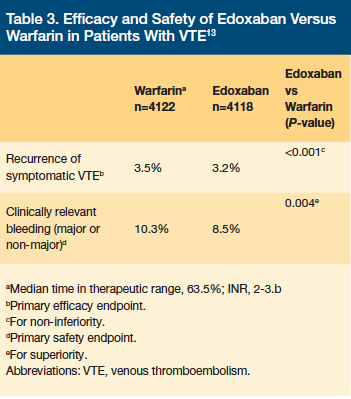

The safety and efficacy of edoxaban for treatment of DVT and PE was evaluated in the Hokusai-VTE trial. This was a double-blind, non-inferiority trial that compared edoxaban to warfarin after acute treatment with heparin.13 Patients were randomized to receive edoxaban 60 mg daily, 30 mg daily, or warfarin for 3–12 months, and all patients were evaluated at Month 12.13 Patients with a CrCl of 30–50 mL/min or body weight less than 60 kg received 30 mg daily of edoxaban.13 The primary endpoints were recurrent symptomatic venous thromboembolism (VTE) and major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding.13 Patients were excluded if they had a CrCl less than 30 mL/min or were receiving more than 100 mg daily of concomitant aspirin or concomitant antiplatelet therapy.13 A total of 8240 patients were enrolled in the trial, and the average patient was 55 years of age, male, and had an unprovoked VTE.13 Between 17.9% and 19.0% of patients had a previous VTE.13 The Hokusai-VTE study demonstrated that edoxaban was noninferior to warfarin for prevention of recurrent symptomatic VTE, with a similar rate of major and clinically relevant non-major bleeding.13 Results for both primary endpoints are shown in Table 3.

Place in Therapy

Prescribing information for edoxaban states that 5182 patients in the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial were 65 years of age or older, and 2838 were 75 years or older.10 A total of 1334 patients in the Hokusai-VTE trial were 65 years of age or older, and 560 were 75 years of age or older. Based on the results of these trials, the annual risk of major bleeding is lower for edoxaban than warfarin (3.1% vs 3.7% in ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48; 1.4% vs 1.6% in Hokusai-VTE).10

For patients with either NVAF or VTE, concomitant use of aspirin, NSAIDS, fibrinolytic therapy, antiplatelets, and antithrombotics with edoxaban will increase the risk of bleeding.10 At this time, there is no reversal agent available for edoxaban, and hemodialysis is unlikely to be beneficial. The elimination half-life of edoxaban (approximately 10–14 hours) may pose an increased risk for older adults with a potential for falls and/or injury.10

Clinicians treating patients with NVAF may find the Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Risk (SPARC) Tool useful. The clinician completes the CHADS2, Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age ≥75 years, Diabetes mellitus, Stroke or TIA previously, Vascular disease, Age 64–75 years, Sex category (CHA2DS2-VASc), and Hypertension, Abnormal renal and liver function, Stroke, Bleeding, Labile INR, Elderly, Drugs or alcohol (HAS-BLED) criterion, and the SPARC tool populates the estimated annual risk of stroke or embolism and major bleeding for several anticoagulants.14 Clinicians can then weigh the risks and benefits for each option, as well as consider cost, dosing, and patient characteristics (weight, renal function, concomitant medications) to make a therapy decision. However, it should be noted that the dabigatran 75 mg dosing is not evaluated by the SPARC tool and that the 2015 Beers Criteria Update recommends avoiding use of dabigatran due to an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and lack of evidence of efficacy and safety for patients with CrCl <30 mL/min.8

For patients with VTE, clinicians should consider the efficacy and cost of each available anticoagulant, availability of reversal agents, and the renal function, bleeding risk, and falls risk of individual patients. Edoxaban has not been directly compared to dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban for prevention of VTE, but it has the advantages of once-daily dosing and a lower monthly cost. In terms of renal impairment, there are also dosing restrictions for the use of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban.

One potential strategy for making complex prescribing decisions in the treatment of atrial fibrillation is shared decision-making (SDM).15 This method involves clinicians and patients working together to determine how to align best practice with the goals, values, and preferences of the patient. The advantages and disadvantages of each treatment option should be clearly described by the clinician, and the patient should communicate any experience or perceptions that they have. A collaborative decision is reached with the acknowledgement that the treatment plan may be revisited using SDM.15 For a patient with atrial fibrillation who may be initiated on a new oral anticoagulant, the clinician should discuss the estimated annual risk of stroke and bleeding, dosing schedule, adverse events, drug interactions, and estimated cost of each agent. The patient should express any concerns regarding this information, such as high cost, risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, and inability to remember twice-daily dosing. Together, the clinician and patient will choose the anticoagulant that would be most efficacious while addressing as many of the patient’s concerns as possible.

Overall, the use of edoxaban for NVAF or VTE should be initiated on a patient-specific basis for older adults, and it should be noted that the 2015 Beers Criteria Update recommends avoiding use of edoxaban in patients with NVAF or VTE with a CrCl <30 mL/min.8 For all patients on anticoagulant agents, the best course of action is regular, standardized clinical monitoring that focuses on adherence assessment, counseling, bleeding risk, renal function, and potential drug interactions.16

Droxidopa

Droxidopa is a centrally- and peripherally-acting alpha/beta agonist approved for the treatment of symptomatic neurogenic orthostatic hypotension (NOH),17 a condition that may be secondary to primary autonomic failure, dopamine beta-hydroxylase deficiency, or nondiabetic autonomic neuropathy.17 Droxidopa is synthesized by dopa-carboxylase to norepinephrine, leading to an increase in blood pressure. Initial dosing is 100 mg three times daily with or without food, with a maximum dose of 600 mg three times daily, and there is no dosage adjustment for advanced age. The use of droxidopa is not recommended for patients with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <30 mL/min, because clinical experience in severe renal impairment is limited and the medication is renally eliminated.17 The estimated AWP of droxidopa ranges from $1858 to $5575 for a 30-day supply, depending on the strength.18

Efficacy and Safety

Droxidopa was evaluated in adults who received the medication for a 14-day, open-label, dose-optimization trial.19 Patients who responded to droxidopa were then randomized to a double-blind, placebo-controlled 7-day trial, after a brief washout period. Patients received their optimized dose from the open-label period, which could be from 100 mg to 600 mg three times daily. The efficacy measures of this study included improvement in mean Orthostatic Hypotension Questionnaire (OHQ) composite score and symptom subscore, as well as mean standing and supine systolic blood pressure (SBP).19 The OHQ includes standing and supine measurements of SBP and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), symptom assessment, and impact of NOH on activities.20 Higher OHQ scores indicate a greater severity of NOH.20

A total of 162 patients were randomized, and the average patient was 55–57 years old, male, and white.19 At the end of the study, the mean daily dose in the droxidopa group was 430 mg, and the mean daily dose of placebo was 381 mg. The average baseline OHQ score was 5.62–5.96, baseline OHQ sub-score was 6.2–6.5, mean standing SBP was 90.7 mmHg, and mean supine SBP was 122.4–127.6 mmHg.19 Results showed that 7-day use of droxidopa resulted in statistically significant improvements in mean OHQ composite score (decrease of 1.83 vs 0.93), mean OHQ symptom subscore (decrease of 1.68 vs 0.95), mean standing SBP (increase of 11.2 mmHg vs 3.9 mmHg), and mean supine SBP (increase of 7.6 mmHg vs 0.8 mmHg).19 The minimally important difference (MID) is defined as 0.8 to 1.00 points for the OHQ composite score and for its two subsections, OH Symptom Assessment (OHSA) and OH Daily Activity Scale (OHDAS).20 Results from this study demonstrated a 0.9-point difference between droxidopa and placebo for OHQ composite score (which meets the MID), but only a 0.73-point difference for OHSA score.19

It is important to note that the efficacy of droxidopa beyond 2 weeks has not been established, as a longer study (8 weeks) did not meet its primary endpoint.17 Therefore, clinicians should use droxidopa with caution and periodically assess efficacy to ensure that the benefits still outweigh the risks (particularly supine hypertension) for individual patients.17

In terms of adverse effects, researchers noted headache, dizziness, nausea, hypertension, and fatigue.17,19 Thus, supine blood pressure should be monitored before and during treatment, as well as during dose increases, and patients should elevate the head of their bed during administration to avoid supine hypertension.17 Patients experiencing excessive hypertension due to overdose should be counseled to remain standing or in a seated position until their blood pressure drops. In patients who continuously experience supine hypertension, droxidopa should be discontinued. Other risks of droxidopa use, based on postmarketing surveillance and on case reports, include hyperpyrexia, confusion, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.17 As droxidopa may exacerbate pre-existing heart disease, caution is necessary in patients who have a history of ischemic heart disease, arrhythmias, or systolic heart failure. For patients with Parkinson’s disease (a source of primary autonomic failure), concomitant use of DOPA decarboxylase inhibitors may prevent the conversion of droxidopa to norepinephrine outside of the central nervous system. This may necessitate an increase in the droxidopa dose.17

Place in Therapy

Droxidopa has been studied in 197 patients age 75 years or older in trials up to 8 weeks, and no overall effects of age on safety and efficacy were observed.17 Few agents are available for the treatment of NOH, and, at this time, droxidopa has only been compared to placebo in trials. Midodrine, an alpha-1 agonist, is taken three times daily to reduce standing blood pressure, and has an estimated monthly cost of $108 to $435. Fludrocortisone, a systemic mineralocorticoid with high glucocorticoid activity, has been used off-label to increase fluid and therefore increase blood pressure. It is dosed as 0.1 mg daily and up to 1 mg daily, and monthly costs are estimated at $22 to $220. Droxidopa, with a monthly cost of $1858 to $5575, is significantly more expensive than midodrine and fludrocortisone.21,22

Conclusion

Clinicians must weigh the risks and benefits of the new medications suvorexant, edoxaban, and droxidopa when prescribing for older adults. Suvorexant has demonstrated improvement in both sleep onset and maintenance and does not need to be adjusted for renal impairment. However, it has not been studied in patients with major psychiatric illness or cognitive impairment, and it has not been studied in many adults 75 years of age or older. There is potential for many drug–drug interactions, CNS adverse effects, and abuse. Until more evidence is available, suvorexant should be avoided in older adults, because it presents similar risks to benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine hypnotics.

Edoxaban is noninferior to warfarin for patients with NVAF and VTE. It has been studied in many older adults with NVAF but in fewer numbers for those with VTE. There is no reversal agent available, and an increased risk of bleeding presents a risk to older adults who may fall. Patients with poor renal function were excluded from studies, and edoxaban has not been studied with concomitant antiplatelets in patients with VTE. The risks and benefits of edoxaban should be compared to other anticoagulation options for patients with NVAF or VTE.

Droxidopa has been shown to improve OHQ scores and increase standing SBP after dose-optimization. Nonetheless, it is not recommended for patients with poor renal function, has not been studied in many patients aged 75 or older, may present a risk of supine hypertension, and has unclear efficacy beyond 2 weeks. It is also uncertain if patients who do not respond to droxidopa within 2 weeks will benefit. There are not many alternative agents for NOH, but if droxidopa is initiated, it is prudent to continuously reassess benefit and risk.

In addition to information about the benefits and risks of new drugs, administration information, individual patient characteristics, and cost should always be considered before prescribing new medications to older adults.

1. FDA Approved Drugs. Center Watch. http://www.centerwatch.com/drug-information/fda-approved-drugs/. Accessed 22 September 2015.

2. Cherubini A, Del Signore S, Ouslander J, et al. Fighting against age discrimination in clinical trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1791-1796.

3. Belsomra [package insert]. Kenilworth, NJ: Merck & Co., Inc. Revised August 2014.

4. Department of Justice. Drug Enforcement Administration. Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of Suvorexant into Schedule IV. 21 CFR Part 1308. Fed Regist. 2014;79(167):51243-51247.

5. Lexi-Comp, Inc. (Lexi-Drugs®). Suvorexant. Lexi-Comp, Inc.; January 3, 2016.

6. Herring WJ, Connor KM, Ivgy-May N, et al. Suvorexant in patients with insomnia: results from two 3-month randomized clinical trials. Biol Psychiatry 2016;79(2):136-148.

7. Michelson D, Snyder D, Paradis E, et al. Safety and efficacy of suvorexant during 1-year treatment of insomnia with subsequent abrupt treatment discontinuation: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2014;13(5):461-471.

8. The American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2015;63(11):2227–2246.

9. Trauer JM, Qian MY, Doyle JS, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(3):191-204.

10. Savaysa [package insert]. Tokyo, Japan: Daiichi Sankyo, Inc. Revised January 2015.

11. Lexi-Comp, Inc. (Lexi-Drugs®). Edoxaban. Lexi-Comp, Inc.; January 3, 2016.

12. Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2093-2104.

13. The Hokusai-VTE Investigators. Edoxaban versus warfarin for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(15):1406-1415.

14. Loewen P. Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Risk (SPARC) Tool. Version 7. http://www.sparctool.com/. Updated January 2015.

15. Seaburg L, Hess EP, Coylewright M, et al. Shared decision making in atrial fibrillation: where we are and where we should be going. Circulation. 2014;129(6):704-710.

16. Gladstone DJ, Geerts WH, Douketis J, et al. How to monitor patients receiving direct oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a practice tool endorsed by Thrombosis Canada, the Canadian Stroke Consortium, the Canadian Cardiovascular Pharmacists Network, and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(5):382-385.

17. Northera [package insert]. Copenhagen, Denmark: Lundbeck NA Ltd. Revised August 2014.

18. Lexi-Comp, Inc. (Lexi-Drugs®). Droxidopa. Lexi-Comp, Inc.; January 3, 2016.

19. Kaufmann H, Freeman R, Biaggioni I, et al. Droxidopa for neurogenic orthostatic hypotension: a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Neurology. 2014;83(4):328-335.

20. Kaufmann H, Malamut R, Norcliffe-Kaufmann L, et al. The Orthostatic Hypotension Questionnaire (OHQ): validation of a novel symptom assessment scale. Clin Auton Res. 2012;22(2):79-90.

21. Lexi-Comp, Inc. (Lexi-Drugs®). Midodrine. Lexi-Comp, Inc.; January 3, 2016.

22. Lexi-Comp, Inc. (Lexi-Drugs®). Fludrocortisone. Lexi-Comp, Inc.; January 3, 2016.