Implementing an SBAR Communication Protocol: A Quality Improvement Project

Primary care providers and nurses in the long-term care setting both acknowledge that a lack of quality communication between parties regarding a resident’s change in medical condition can result in avoidable, unnecessary hospitalizations of residents, placing them at risk for dangerous and costly complications. The timing, clarity, and content of information, as well as the nurse’s ability to synthesize and communicate key clinical information to the primary care provider, are key determinants of these outcomes. SBAR is a communication tool that provides a systematic approach for nurses to assess and record change in resident status. A quality improvement project based on the use of the SBAR protocol was implemented in the long-term care setting. The authors provide a preliminary report of the uptake of the intervention and its effect on unplanned hospital transfer rates.

Key words: Communication, avoidable hospitalizations, quality improvement

Abstract: Primary care providers and nurses in the long-term care setting both acknowledge that a lack of quality communication between parties regarding a resident’s change in medical condition can result in avoidable, unnecessary hospitalizations of residents, placing them at risk for dangerous and costly complications. The timing, clarity, and content of information, as well as the nurse’s ability to synthesize and communicate key clinical information to the primary care provider, are key determinants of these outcomes. SBAR is a communication tool that provides a systematic approach for nurses to assess and record change in resident status. A quality improvement project based on the use of the SBAR protocol was implemented in the long-term care setting. The authors provide a preliminary report of the uptake of the intervention and its effect on unplanned hospital transfer rates.

Key words: Communication, avoidable hospitalizations, quality improvement

Citation: Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging. 2015;23(7):27-31.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Nursing home residents are prominent users of the emergency department, accounting for more than 2.2 million visits annually.1 These residents demonstrate higher acuity than non-nursing home residents, are more likely to have been discharged from the hospital within the prior 7 days, are more likely to be admitted to the hospital, and exhibit higher mortality.1 Hospitalizations of nursing home residents are associated with iatrogenesis, lifestyle disruption and discomfort, and increased cost.2-4 It is estimated that 50% of these hospitalizations are avoidable5-7 and are due in large part to problems identifying, communicating, and responding to changes in the resident’s medical condition.8,9 Lamb8 found that greater attention should be paid to the reasons that staff provide for hospital transfers in order to reduce avoidable hospitalizations. Nurses are aware of the intricacies of the transfer process, how family member requests influence care, the extent to which advance directives are discussed, and whether medical providers are offered the option to treat conditions within the nursing home.

Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT II) is a quality improvement intervention designed to support effective clinical decision-making when a resident experiences a change in status.2,5 INTERACT II includes care paths and educational materials that focus on improving the identification, evaluation, and management of acute changes in the condition of nursing home residents.2 A key component of INTERACT II is the SBAR communication tool, which provides a systematic approach for nurses to assess and record change in resident status. Components of SBAR include a description of the Situation (symptoms, onset, duration, aggravating/relieving factors, and other observations); Background of the change (including primary diagnosis, pertinent history, vital signs, functional change, mental status change, medications, pain, laboratory studies, allergies, and advance directives); Assessment of appearance (by the regeistered nurse [RN] or licensed practical nurse [LPN]), including a description of the perceived with the resident or making a statement of the perceived problem; and, Request for action (eg, provider visit, lab work, intravenous fluids, observation, change in orders, or transfer to hospital).2

Effective implementation of INTERACT II has been associated with substantial reductions in hospitalization of nursing home residents.10,11 In a previously published quality improvement project that utilized the SBAR protocol, the majority (87.5%) of nurse respondents found the SBAR protocol useful for organizing information and providing cues on what to communicate to medical providers.12 Additionally, physicians indicated that SBAR use improved the quality of information that nurses provided and that the information influenced their decisions to hospitalize or not hospitalize residents. We describe the implementation of a quality improvement project based on the use of the SBAR protocol and provide a preliminary report of the uptake of the intervention and its effect on unplanned hospital transfer rates.

METHODS

SBAR Protocol Implementation

This project employed a single-site repeated measures design. The project was implemented over 4 months in a 137-bed skilled nursing home, part of a not-for-profit continuing care retirement community in suburban Pennsylvania. All staff nurses, including RNs (n=21) and LPNs (n=19), and all physicians (n=7) participated in the project with the support of the facility administration, including the medical director. Nurses were informed about the project via posted flyers and informational sessions, and the physicians were oriented to the project by the medical director. The project was reviewed by the New York University Committee on Activities Involving Human Subjects (NYUCIHS) and was considered an exempt study.

Our approach to this project was guided by Kotter’s Eight Step Change theory,13 which outlines a process for creating systemic change within an organization. A key element of this approach is establishing stakeholder support around the need for change: in this case, commitment from administrators and clinicians to improving communication between nurses and medical providers regarding changes in resident condition. Table 1 provides an overview of how the implementation of this project aligned with these eight steps.

Nurse training is a key element of the SBAR protocol. All nurses received training on the purpose and use of the SBAR communication tool. Clinical case scenarios, based on realistic examples provided by staff, were utilized to demonstrate data collection and communication techniques when staff members encounter a change in the resident’s condition. Training exercises addressed the application of the SBAR tool and reviewed common reasons for unplanned transfers, including exacerbation of congestive heart failure, respiratory and urinary tract infections, and falls, as well as for those occurring in residents with dementia. In-service training occurred over approximately eight sessions for 45 minutes per session in order to accommodate the nursing staff schedule. Nonparticipants of the study, including facility staff, residents, families, and corporate staff, received information about the project through newsletters, routine meetings, and flyers posted in key areas.

Assessments of Quality Improvement

Intervention Uptake. The intervention uptake was evaluated in terms of: (1) SBAR quality (as measured by the completeness of the SBAR form) and (2) SBAR timeliness (as measured by whether form was completed before the call to the medical provider was made). Feedback was also provided continuously to the nursing staff on the quality of SBAR documentation (completion and timeliness).

In a series of four meetings, nurses provided feedback to the quality improvement project team regarding the facilitators and barriers to SBAR protocol implementation. This feedback was recorded, and the suggestions for change that were offered were itemized.

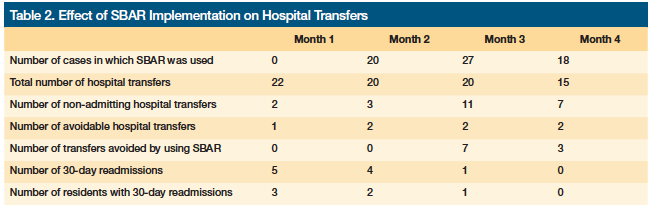

Effect of SBAR Implementation on Hospital Transfers. The medical director initiated a process to evaluate the medical records of all residents who experienced an unplanned transfer to a hospital to determine if the transfer could be classified as unplanned/avoidable or unplanned/unavoidable. The INTERACT II Unplanned Hospital Transfer Evaluation Tool2 was used to pull the following information from the medical records: total number of discharges, deaths, planned/unplanned/transfers to emergency room, planned/unplanned transfers with hospital admission, and any transfer that occurred within 30 days of hospital discharge. The medical director and medical records administrator developed a system to identify and track transfers to the hospital based on the information identified via the tool. In addition to the number of hospital transfers that were avoidable (as determined by the medical director), data tracked for the 1 month pre-implementation and the 3 months post-implementation included: number of cases in which SBAR was used, total number of unplanned hospital transfers, number of transfers not admitted to the hospital, transfers avoided by using SBAR (number of cases in which SBAR was used minus the number of unplanned transfers), and total number of 30-day hospital readmissions (as well as the incidence and prevalence among residents). The medical director conducted reliability checks to validate that information collected by the medical records director was complete and accurate. The medical records staff received training on how to collect this hospital transfer data and record the information on the transfer log. Results of this analysis were communicated to the medical records director, the medical records administrator, and the director of nursing on a weekly basis, and to the quality improvement project committee on a monthly basis. Results were also shared with staff via postings in the unit.

Cost–Benefit Analysis. Another outcome measure for the study was a cost–benefit analysis. The total cost of the project was calculated, and the potential cost savings, based upon the average cost of the hospitalization of a nursing home resident, were estimated.3

RESULTS

Intervention Uptake

The medical records director determined that SBARs were completed for 100% of unplanned transfers to the hospital emergency department. The timeliness of the SBARs was 72% during the first month. The reasons for lack of timeliness in the remaining 28% of the cases were explored. We recognized that nurses were not aware of necessary versus extraneous content and thus were taking too much time to complete the tool. Nurses were re-educated with a review of actual discharged cases to illustrate salient points to document. Subsequent audits after the second, third, and fourth month of implementation showed 90% of SBARs were completed in a timely fashion, and 100% completion of SBARs was sustained.

The nurses reported that they benefited from feedback regarding the effect of SBAR quality and information on the number of unplanned transfers, as this information supported buy-in for the project. The respect demonstrated by the physicians (as exemplified by nurses’ reports of “feeling heard”) also provided a positive reinforcement. Additionally, the nurses reported that uptake of the SBAR protocol was facilitated by having someone (ie, the medical records director) take ownership of ensuring that the necessary tools were available and accessible.

Effect of SBAR Implementation on Hospital Transfers

As shown in Table 2, the total number of transfers declined over the early period of SBAR protocol implementation. This occurred despite an increase in non-admitted transfers (transfers that resulted only in emergency room treatment) during the month of December, which include treatment for injuries. The number of avoidable hospital transfers remained constant during the 4 months of implementation (mean, 1.75 transfers per month). The most prevalent admitting diagnoses for avoidable hospital transfers were urinary tract infection, transient ischemic attack, and respiratory infections. The hospital transfers avoided during implementation were calculated by subtracting the total number of transfers from the SBARs completed during each month. Seven transfers were avoided during Month 3 of implementation; three were avoided during Month 4. The number of 30-day hospital readmissions (both the incidence and number of residents readmitted) showed a steady decline over 4 months, with no 30-day readmissions to the hospital at the end of 4 months.

Cost–Benefit Analysis

The total cost of the pilot project was $4,355.00, including the costs of materials, staff replacement, data analysis, and medical record review time by the medical director. Potential cost savings to Medicare resulting from an overall reduction in avoidable hospital transfers (n=10) over a four month period was $109,350 (based on an average cost of $10,935 for hospital admissions from nursing homes).3

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this quality improvement evaluation was to examine the feasibility of using SBAR as a structured method for nursing staff to collect and communicate data pertaining to change in resident status in a long-term care facility. The preliminary influence of the implementation of this protocol on unplanned hospital transfers was also evaluated.

The SBAR forms were completed thoroughly, in a timely manner, and with high-quality clinical data. Integration of the SBAR system into the electronic medical record would likely increase staff adherence and the tool’s utility.14 Although beyond the scope of this project, improvement in communication using SBAR may improve physician–nurse collaboration and job satisfaction. Other benefits might include improved resident satisfaction with care, improved quality of care and patient outcomes,15 improved nursing competencies, increased quality/quantity of nursing assessment data, reduced adverse drug events,15 an improved quality of medication prescribing,16 and improved time efficiency for nurses between identification of change and action.

Consistent with previously published studies,10,16 SBAR utilization was associated with a trend toward fewer overall unplanned hospital transfers, fewer 30-day readmissions to the hospital, and more transfers avoided. The low rate of avoidable transfers was maintained. The overall calculated transfer rate was reported differently than in other studies. Ouslander10 reported the rate as hospitalizations per 1,000 resident-days, whereas, for this project, the total number of transfers to the emergency department was determined, as well as the number of transfers that were non-admitting. Over the 4-month implementation period, the total transfers decreased, even as the non-admitting transfers slightly increased; this was due mostly to the type of clinical situation presenting, such as suturing for lacerations or prompt radiological assessment for a fall, that only required emergency room care. Thirty-day readmission rates fell dramatically during the implementation period. Monthly transfer rates as well as 30-day readmissions decreased over the implementation period, while SBAR utilization increased.

The number of avoided transfers increased from 0 to 7 in the third month of implementation as a result of increased SBAR utilization. This improvement was likely the result of reinforcement of SBAR tool utilization through direct staff education and the convening of a medical staff meeting to discuss the plan to address the rise in 30-day hospital readmissions. The designation of avoidability of hospital transfers deserves further discussion. An analysis of conditions that can be safely and appropriately managed in the nursing home setting assists in designating hospital transfers as avoidable versus unavoidable.2 For this project, the number of avoidable hospital transfers as determined by the medical director remained very low during project implementation (mean, 2 per month). There were several identified reasons why this number remained the same despite the observed rise in SBAR utilization and decrease in overall hospital transfers. The designation of a transfer as avoidable requires the consideration of many factors that influence transfer to the hospital, including resident and family preference, medical provider authorizing transfer (primary vs. covering), and the description of the change in clinical condition and presumptive diagnosis. Thus, the evaluator, typically a medical provider, determines the avoidability of a transfer without consideration of staff perspectives. Possible confounding factors could include the personal perspectives of the evaluator and lack of experience and preparation of the evaluator to conduct this type of analysis. A more precise definition of avoidable transfers is warranted, according to the facility medical director, consistent with the findings of Lamb and colleagues.8

The project had several limitations to its generalizability. The intervention was only implemented at a single site, and one that has an AMDA-certified medical director, which is not common in the nursing home industry and thus is not generalizable to the “typical” facility. The abbreviated time period for data collection limited the ability to evaluate a potentially full and sustained impact. The determination of whether hospital transfers were avoidable was solely made by the medical director without the input of other staff or a non-biased data collector. Finally, other factors that can impact hospital transfers (patient acuity and organizational factors) were not included in the analysis.

For acute care providers, there is a financial imperative to reduce costly 30-day readmissions to the hospital. Alternately, nursing homes are challenged by high acuity hospital admissions/readmissions, which are costly and resource-intensive. It is in the best interest of nursing homes and hospitals to form strong partnerships to examine care transition processes to reduce the incidence of re-hospitalization as well as assure older adults are not discharged with unstable health conditions that nursing homes are not prepared clinically or financially, to manage. The communication process between the physican and the nurse is a critical factor influencing the decision to hospitalize; however it is only one of several factors that influence this decision. The quality and quantity of the medical visits, the availability and clinical competence of nursing staff, and operational procedures related to care coordination and transitions planning, clinical care, medication management1,17 and advance care planning require consideration.18 Thus, a comprehensive, systemic approach is warranted to promote effective decision-making related to hospitalization of nursing home residents.

CONCLUSIONS

This quality improvement project engaged all nursing staff, physicians, administrators, and corporate staff. The management team continues to audit completion and timeliness of the SBAR communication and shares results with nursing and medical providers. Hospital transfers are a standing item on the Quality Improvement Committee agenda, are reviewed monthly, and are reported to corporate staff. The broad involvement of stakeholders was critical to implementation, and has afforded the opportunity for ongoing evaluation of the care provided to residents who experience a change in condition. As hospitalizations are evaluated for appropriateness, the root cause analyses will include the use of SBAR and will facilitate further exploration of other factors influencing the decision to hospitalize. In conclusion, this interdisciplinary quality improvement project can be implemented at low cost in any long-term care facility. The SBAR tool is a feasible method to provide structured communication between nurses and medical providers with the potential to positively influence decision-making to hospitalize nursing home residents.

References

1. Saliba D, Kington R, Buchanan J, et al. Appropriateness of the decision to transfer nursing facility residents to the hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(2):154-163.

2. Ouslander J, Lamb G, Perloe M, et al. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations of nursing home residents: frequency, causes, and roots. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:627-635.

3. Spector W, Mutter R, Owens P, Limcangco R. Transitions between Nursing Homes and Hospitals in the Elderly Population, 2009. HCUP Statistical Brief #141. https://1.usa.gov/1KcbU1v. September 2012.

4. Hain D, Tappen R, Diaz S, Ouslander JG. Characteristics of older adults rehospitalized within 7 and 30 days of discharge. J Gerontol Nurs. 2012;38(8):32-44.

5. Xing J, Mukamel DB, Temkin-Greener H. Hospitalizations of nursing home residents in the last year of life: nursing home characteristics and variation in potentially avoidable hospitalizations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):1900-1908.

6. Dosa D. Should I hospitalize my resident with nursing home-acquired pneumonia?. JAm Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7(Suppl 3):S74-80, 73.

7. Feng Z, Coots LA, Kaganova Y, Wiener JM. Hospital and ED use among medicare beneficiaries with dementia varies by setting and proximity to death. Health Aff (Milwood). 2014;33(4):683-690.

8. Lamb, G, Tappen R, Diaz S, Herndon L, Ouslander JG. Avoidability of hospital transfers of nursing home residents: perspectives of frontline staff. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(9):1665-1672.

9. Abrahamson K, Mueller C, Davila HW, Arling G. Nurses as boundary-spanners in reducing avoidable hospitalizations among nursing home residents. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2014;7(5):235-243.

10. Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Tappen R. Interventions to reduce hospitalizations from nursing homes: evaluation of the INTERACT II collaborative quality improvement project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):745-753.

11. Ouslander JG, Bonner A, Herndon L, Shutes J. The Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) quality improvement program: an overview for medical directors and primary care clinicians in long term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(3):162-170.

12. Renz S, Boltz M, Wagner L, Capezuti E, Lawrence T. Examining the feasibility and utility of an SBAR protocol in long-term care. Geriatr Nurs. 2013;34(4):295–301.

13. Kotter J. Leading change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review press; 1996.

14. Handler S, Sharkey S, Hudak S, Ouslander JG. Incorporating INTERACT II clinical decision support tools into nursing home information technology. Ann Longterm Care. 2011;19(11):23-26.

15. Tjia J, Mazor K, Field T, Meterko V, Spenard A, Gurwitz JH. Nurse-physician communication in the long-term care setting: perceived barriers and impact on patient safety. J Patient Saf. 2009;5(3):145-152.

16. Field T, Tjia J, Mazor K, et al. Randomized trial of a warfarin communication protocol for nursing homes: an SBAR-based approach. Am J Med. 2011;124(2): 179.e1-179.e7.

17. Feigenbaum P, Neuwirth E, Trowbridge L., et al. Factors contributing to all-cause 30-day readmissions. Med Care. 2012;50(7):599-605.

18. Happ M, Capezuti E, Strumpf N, et al. Advance care planning and end-of-life care for hospitalized nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(5):829-835.