Implementing Medication Assistants in One Eastern Washington Nursing Home

Abstract: In response to the shortage of licensed practical nurses and registered nurses in area nursing homes (NHs), the Geriatric Interest Group of Spokane (GIGS), Washington, a group of long-term care (LTC) professionals from 5 local NHs, initiated the development and launch of a certified medication assistant (MA-C) training program in Eastern Washington. The purpose of this article is to describe the planning, implementation, and evaluation of an MA-C quality improvement initiative in the 50-bed LTC unit of one Eastern Washington NH. MA-Cs were successfully added to the staffing model in the NH. Quality outcome measures such as the medication error rate, staff satisfaction, the number of residents per month returned to the hospital, call light response rate, and the number of resident falls per month improved after implementation without costing the NH significantly more money in staff salaries. Based on these encouraging findings, GIGS plans to replicate the initiative in 3 additional NHs.

Key words: medication assistant, nursing home, quality improvement

In 2013, the Washington State Legislature passed a law that allowed certified medication assistants (MA-Cs) to administer certain medications to residents in nursing homes (NHs). Specifically, the law as codified in the Washington Administrative Code states that “a nursing assistant-certified with a medication assistant endorsement administers medications and nursing commission-approved treatments to residents in nursing homes, under the direct supervision of a designated registered nurse.”1

In order for a nursing assistant-certified to obtain a medication assistant endorsement in Washington, he or she must meet the following requirements2:

Be a nursing assistant-certified in good standing under Washington law

Complete a nursing commission-approved medication assistant educatio and training program3

Complete at least 1000 hours of employer-confirmed work experience in an NH as a nursing assistant-certified in the year prior to application

Pass a competency evaluation (ie, a written examination)

With this opportunity in mind, the Geriatric Interest Group of Spokane (GIGS) began investigating the possibility of launching an MA-C training program to answer the shortage of licensed practical nurses (LPNs) and registered nurses (RNs) in local NHs. GIGS was formed in 2012 by the principal investigator as a group of long-term care (LTC) professionals (eg, directors of nursing, administrators, social workers, and RNs) from 5 local NHs whose goal is to provide a forum for quality initiatives aimed at improving care in NHs.

Two large-scale multistate studies support the use of MA-Cs in NHs. In a study sponsored by the Arizona State Board of Nursing, a statewide medication technician program was developed and pilot tested in 6 nursing facilities between 2004 and 2008.4 The researchers found no significant difference in patterns of medication errors before and after implementation of the program. Specifically, the mean medication error rate at baseline was 10.4% (LPNs, 10.12%; RNs, 11.54%). After implementation, the mean medication error rate was 6.6% (LPNs, 7.25%; RNs, 2.75%; medication technicians, 6.06%). In short, the overall mean medication error rate decreased 3.8% after implementation of the program.

Another large-scale multistate study to determine the impact of medication aide use on NH quality was conducted from 2004 to 2010 in 8 NHs in the southwestern United States.5 The researchers analyzed staffing levels and inspection deficiencies from the federal government’s Online Survey and Certification and Reporting System database and Nursing Home Compare quality indicators. They found that the use of medication aides decreased the probability that a NH received a deficiency for a medication error rate of 5% or higher. In fact, they found that the use of medication aides was associated with fewer pharmacy deficiency citations and a decreased use of physical restraints on residents.

The purpose of this article is to describe the planning, implementation, and evaluation of an MA-C quality improvement initiative in one Eastern Washington NH. We hypothesized that, if the mundane task of routine medication administration were assigned to another professional, nurses would have more time to coordinate care, assess the ongoing needs of residents, and supervise caregivers.

Methods

In preparation for the project, we first queried nursing staff to identify the potential barriers to adding MA-Cs to the staffing model of one or more local NHs.6 The 15-item Medication Assistant Endorsement Program Survey was developed and pilot tested with 218 employees from 5 local GIGS NHs.6 The results showed that nursing assistants were the most supportive of the new initiative. LPNs were the least supportive, possibly fearing job loss with the addition of MA-Cs to the staffing model. With this in mind, the GIGS group agreed that no licensed nurses would lose their jobs as a result of the MA-C initiative.

Design

As a quality improvement initiative, this project used the Model for Improvement as its theoretical framework.7 This model provides the basic framework of PDSA (plan, do, study, act)—that is, planning a change, implementing it, evaluating the results, and disseminating or acting on the findings.

Participants

GIGS is comprised of health care professionals (directors of nursing, administrators, social workers, and RNs). Management personnel from the Health Care Training Center (HCTC), a medical training and certification institute in Spokane Valley, Washington, joined the group in 2016 in response to our MA-C initiative. Working closely with GIGS, professionals from HCTC developed an MA-C training program based on the National Council of State Boards of Nursing’s Medication Assistant-Certified (MA-C) Model Curriculum,8 and then obtained approval from the Washington State Department of Health to offer the training program.

Setting

The GIGS group decided to pilot the initiative in a single NH before implementation at other GIGS-represented NHs with the rationale that it would be easier to control for problems with processes and to adjust the plan if the initiative were launched in a single NH rather than 2 or 3 simultaneously.

The administrator and the director of nursing of one of the GIGS NHs in Spokane volunteered the use of their site for this pilot project. The NH is a 120-bed skilled nursing facility that offers transitional care and skilled and LTC services. The NH management team selected the facility’s 50-bed LTC unit as the site for the addition of MA-Cs to the staffing model.

Implementation

After selection of the NH as the site for the pilot project, the GIGS group met to discuss the process of selecting MA-C candidates from the current nursing assistant staff. Each NH invited candidates for their program based on the following criteria:

Career nursing assistant with a minimum of 3 years of experience

Proven loyalty to the NH (eg, limited absences, willing to work extra shifts)

Evidence of critical thinking skills

Emotional maturity

Displays positive attitude

Team player (ie, works well with others)

Good preceptor

As a group, GIGS also reviewed current nursing assistant, LPN, and RN hourly wages from GIGS NHs and arrived at a starting hourly wage of $16.00 for the MA-C. This hourly wage was midway between the hourly wage for a nursing assistant and an LPN and was thought to be equitable secondary to the added responsibilities of the MA-C as described in the MA-C job description, newly developed by the GIGS group. The job description was based on the MA-C’s scope of practice, education, and demonstrated competency as described in the Washington Administrative Code.9

Changes to staffing model at targeted facility/unit. The GIGS group decided to limit the addition of the MA-C(s) to the day shift. Day shift nurses administer the majority of medications; thus, it was thought that the addition of MA-Cs to the day shift would have the biggest impact on nurse workload.

A time study was conducted to determine the amount of time (minutes/hours worked) that a MA-C could be assigned as described in the MA-C job description. It was determined that there were enough tasks that an MA-C could complete in an 8-hour day shift.

The day shift staffing model was changed from 2 LPN/RNs (1 per medication cart) and a unit manager to 2 MA-Cs, a charge nurse, and a unit manager. This led to the addition of 1 staff member. No LPNs or RNs lost their jobs as a result of the addition of the 2 MA-Cs. The new staffing model was implemented 5 days per week, Tuesday through Saturday.

MA-C training program. The HCTC’s MA-C training program is 104 hours long, comprising 12 days (64 hours) of didactic content and 40 hours (5 days) of practicum. An RN presented the didactic content in a classroom setting at the HCTC’s main campus. The practicum experience was conducted at the student’s employer NH and was supervised by an onsite RN preceptor. All students enrolled in the first training cohort passed the Washington State medication assistant competency evaluation (written examination) on their first attempt.

Orientation of new MA-Cs to the unit. The targeted NH selected 2 nursing assistants to begin their transition to MA-Cs. Once training was complete and the endorsement had been awarded by the Washington State Department of Health, the nurse management team scheduled the 2 new MA-Cs for 2 weeks of orientation. Orientation consisted of observation and an in-depth medication pass/treatment skills audit. Other unit staff (ie, nursing assistants, LPNs, RNs) were oriented to the new staffing model and new roles and expectations.

Weekly team meetings and daily huddles were conducted to reinforce and reassure all staff members. Role delineation and supervisory responsibilities were reviewed to ensure all participants were able to operationalize the new staffing model. The MA-Cs underwent brief weekly skills audits leading up to the NH’s annual state survey for Medicare/Medicaid certification.

Measurement

The GIGS professionals agreed on outcome measures (Table 1), with measurements occurring at baseline (time 1 – January 2017) and then 3 months after the addition of MA-Cs to the staffing model in the 50-bed LTC unit at the targeted NH (time 2 – April 2017). These outcome measures included staff, resident, and organization measures; specifically, they were the medication error rate, staff satisfaction, the number of residents per month who returned to the hospital, the call light response rate, and the number of resident falls per month.

Data Analysis

The 15-item Medication Assistant Endorsement Program Survey6 data were collected, entered into an Excel spreadsheet, and then entered into IBM SPSS Statistics 24 statistical software. The original survey used a 5-point scale, with 1 indicating “strongly agree” and 5 indicating “strongly disagree.” In order to facilitate the interpretation of the results, the data were reverse-coded such that 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 5 indicated “strongly agree.”

A paired t test was conducted in order to determine the differences between the survey item scores from time 1 to time 2. This analysis showed a number of significant differences between the mean scores of certain survey items from time 1 to time 2.

Results

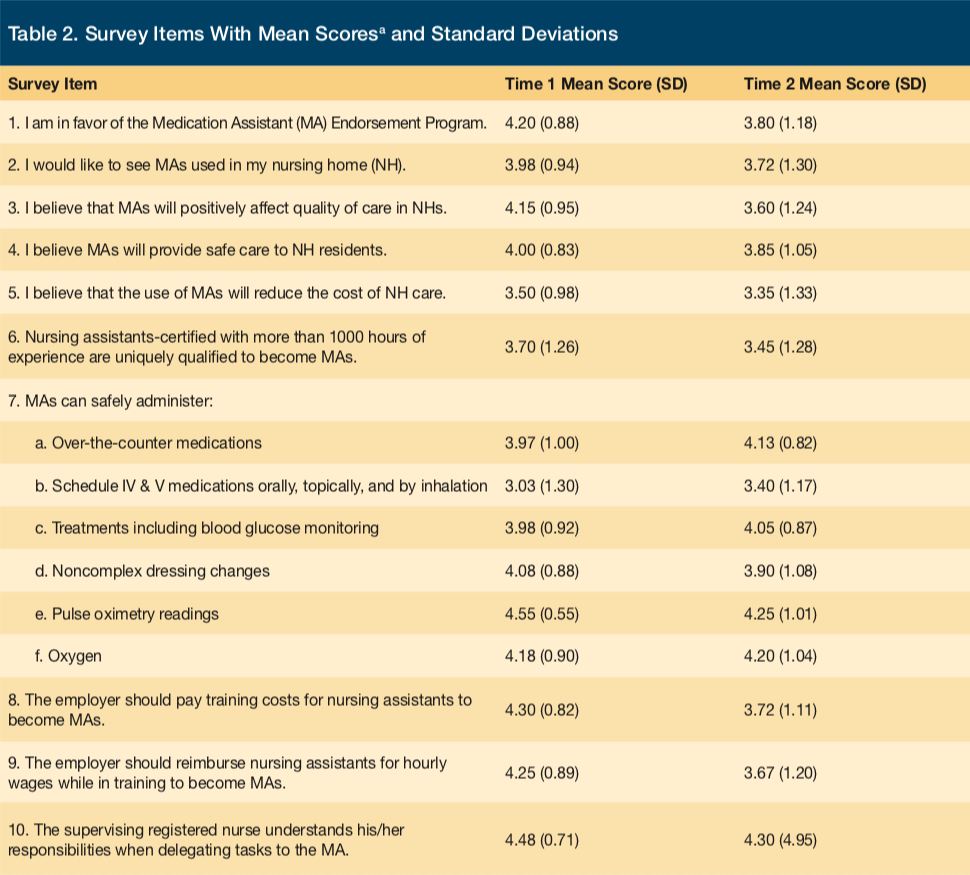

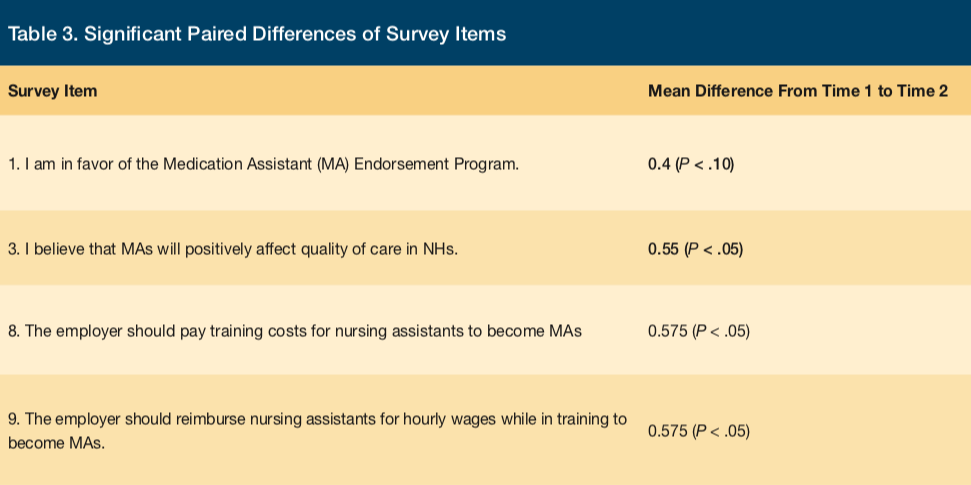

Table 2 summarizes the means and standard deviations, and Table 3 summarizes the significant paired differences.

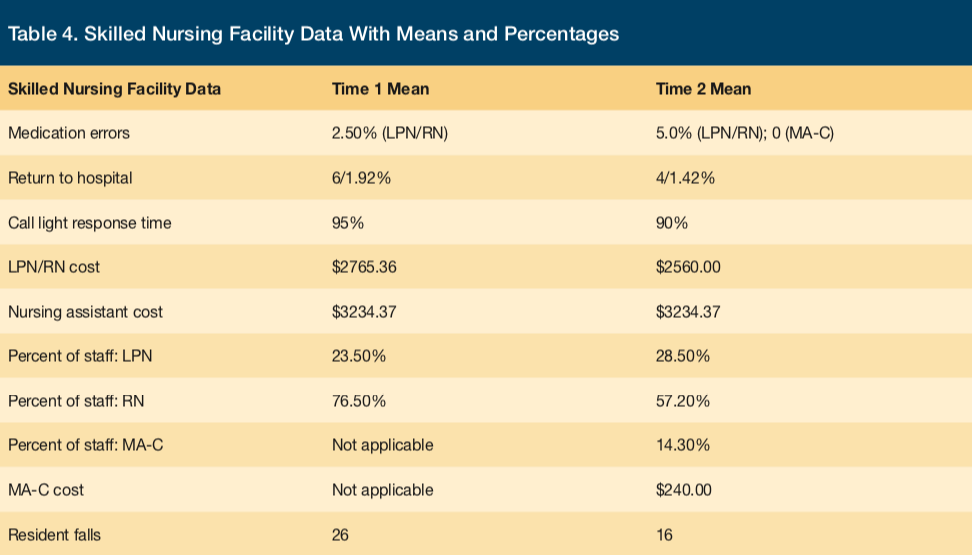

Table 4 provides facility outcome measures pertinent to the 2 time periods.

Discussion

In this ongoing quality improvement project, MA-Cs have successfully administered medications to stable LTC residents of one 50-bed unit in the studied time period. Most facility outcome measures improved after the addition of the MA-Cs to the staffing model. In support of the hypothesis that assigning the mundane task of routine medication administration to MA-Cs would allow nurses to have more time to coordinate care, assess the ongoing needs of residents, and supervise caregivers, the results showed that fewer residents were transported back to the hospital and that the number of resident falls declined significantly after implementation. The positive changes in outcomes occurred without a significant increase in personnel costs. In fact, total nursing staff costs increased only minimally after the addition of MA-Cs, making the initiative affordable for most NHs.

Based on the significant-difference findings, the MA-C initiative at the targeted NH was deemed successful, albeit with some initial difficulties in adapting to the new processes. Typically, every organizational change will yield similar results, wherein the first phase after implementation sees a decrease in attitudes, but once employees become more experienced with the new MA-Cs and their skills, we anticipate an improvement in attitudes.

Based on data in Table 3, the MA-C initiative had some effects on the nurses’ responses to certain survey items. For instance, after MA-Cs were included in the staffing model, nurses tended to have a less-favorable opinion of MA-Cs than they had before implementation of the new staffing model (a partially significant decrease of 0.4 units). Additionally, nurses were less likely to believe that MA-Cs were a positive influence on the quality of care in their nursing facilities (a strongly significant decrease of 0.55 units).

After initiating the MA-C within the staffing model, the nursing assistants’ initial enthusiasm for the training initiative decreased somewhat. This suggests that the MA-C initiative had some problems related to administration and implementation. Even though they deemed the MA-C initiative to be less of a positive influence for their NH, the nursing assistants’ scores do not indicate that they were opposed to MA-Cs; rather, they were just not as enthused as they had been initially. Perhaps the nurses were resistant to change or found the addition of MA-Cs to the staffing model cumbersome, resulting in a slight reduction in their positive feelings after implementation of the MA-C program on the unit. This suggests that the MA-C initiative may need more time for individuals to adjust and to gain experience. Perhaps the NH administrators and leadership could have emphasized this to the nursing staff so as to make them aware that a learning curve would be associated with the new staffing model. Doing this also should be considered in other NHs, especially to ensure that nursing staff continue to find the MA-C initiative useful and buy in to it.

At baseline, the respondent nursing assistants expected their employer (ie, the NH) to pay for the training (a strongly significant decrease of 0.575 units), as well as to reimburse them with hourly wages for the time spent for training (a strongly significant decrease of 0.575 units). These expectations were reduced after implementation of the new staffing model. These findings suggest that the nursing assistants were not fundamentally opposed to paying for the training themselves, nor did they expect to be reimbursed for their time while undergoing training. This was a surprising finding that could be an interesting factor supporting implementation of the MA-C initiative. For instance, an NH may not have the necessary funds to pay for the training and to reimburse staff for wages during training. If the nursing assistants believe that the training will benefit them in the future (eg, increased salary, increased expertise), then they may be less likely to expect their employer to pay for the training and wage reimbursement. An advantage of this is that the NHs would be assured that they are attracting candidates who are genuinely interested in becoming MA-Cs.

The monthly personnel costs before implementation of the new staffing model were $2765.36 for LPN and RN staff and $3234.37 for nursing assistants (total, $5999.73). The month following the addition of MA-Cs to the new staffing model, LPN and RN costs were lowered to $2560.00, nursing assistant costs were unchanged, and MA-C costs were $240.00 (total, $6034.37). Overall, the addition of MA-Cs to the staffing model led to a total increase of $34.64 for the month following the change. This is encouraging in that the increase in personnel costs was not significant.

Historically, research has suggested that medication error rates do not significantly differ between MA-Cs and nurses (LPNs and RNs ).4,5,10-12 In our project, medication errors were zero for MA-Cs, unlike for the facility’s licensed nurses. We hypothesize that the MA-Cs were error-free because they were new to the process, were keenly focused on their new role, and did not experience the multiple interruptions that plague most nurses administering medications to residents in NHs.10 The licensed nurse (LPN and RN) medication error rate at baseline were 2.5%. At 3 months after implementation, the medication error rate increased to 5% for licensed nurses but was zero for MA-Cs. This is not surprising, given that licensed nurses could be interrupted multiple times during a medication pass,10 whereas MA-Cs are taught to focus on their role and not on other tasks.

The number of residents who returned to the hospital decreased after implementation of the MA-C initiative. This is encouraging in that we hypothesized that, with the addition of MA-Cs, the charge nurse would have more time to assess the needs of residents if he or she did not have to administer routine medications. A decrease from 6 to 4 resident transfers to the hospital after implementation of the MA-C initiative was encouraging, but more data are needed.

The standard at the targeted NH for call light response time is 3 minutes for bathroom call lights and 5 minutes for room call lights. At baseline, call light response times were met 95% of the time. After adding the MA-C to the staffing model, time 2 response times were met 90% of the time. Even though the facility reported a decline in reported call light response times, all bathroom call lights were answered within 5 minutes and room call lights were answered within 10 minutes at time 2.

An important measure of quality is the number of resident falls. In the 6 months before the addition of MA-Cs to the staffing model on the targeted unit, the total number of falls was 26. All were noninjury falls. In the 6 months after the addition of MA-Cs, the total number of falls decreased to 16, a decrease of 61.5%. All were noninjury falls.

Conclusion

When facing a shortage of licensed nurses, MA-Cs are a viable alternative to licensed nurses in the administration of routine medications to residents of NHs. Based on the encouraging findings from this pilot, GIGS plans to replicate the initiative in 3 additional NHs in 2018.

References

1. Medication assistant endorsement: applicability. Washington Administrative Code §246-841-586. https://app.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=246-841-586. Effective July 8, 2013. Accessed January 24, 2018.

2. Medication assistant endorsement: application requirements. Washington Administrative Code §246-841-588. https://app.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=246-841-588. Effective July 8, 2013. Accessed January 24, 2018.

3. Medication assistant endorsement: requirements for approval of education and training programs. Washington Administrative Code §246-841-590. https://app.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=246-841-590. Effective July 8, 2013. Accessed January 24, 2018.

4. Randolph PR, Scott-Cawiezell J. Developing a statewide medication technician pilot program in nursing homes. J Gerontol Nurs. 2010;36(9):36-44.

5. Walsh JE, Lane SJ, Troyer JL. Impact of medication aide use on skilled nursing facility quality. Gerontologist. 2014;54(6):976-988.

6. Dupler AE, Crogan NL, Beqiri M. Medication assistant-certification program in Washington State: barriers to implementation. Geriatr Nurs. 2015;36(4):322-326.

7. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. How to improve. https://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/default.aspx. Accessed January 24, 2018.

8. Medication Assistant-Certified (MA-C) Model Curriculum. Chicago, IL: National Council of State Boards of Nursing; 2007. https://www.ncsbn.org/07_Final_MAC.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2018.

9. Medication assistant endorsement: medication administration and performing prescriber ordered treatments. Washington Administrative Code §246-841-589. https://app.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=246-841-589. Effective July 8, 2013. Accessed January 24, 2018.

10. Dilles T, Elseviers MM, Van Rompaey B, Van Bortel LM, Vander Stichele RR. Barriers for nurses to safe medication management in nursing homes. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2011;43(2):171-180.

11. Scott-Cawiezell J, Pepper GA, Madsen RW, Petroski G, Vogelsmeier A, Zellmer D. Nursing home error and level of staff credentials. Clin Nurs Res. 2007;16(1):72-78.

12. Young HM, Gray SL, McCormick WC, et al. Types, prevalence, and potential clinical significance of medication administration errors in assisted living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1199-1205.

13. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Advance Copy–Changes for Sub-Task 5E, Medication Pass Observation Protocol for Long Term Care (LTC) Facilities. June 7, 2013. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-13-36.pdf. ccessed January 24, 2018.

To read more ALTC expert commentary and news, visit the homepage