The Impact of Federal Health Care Reform on LTC

Despite the failure of the American Health Care Act (AHCA)1 to make it to Congress for a vote, the principles outlined within it provide insight into the direction that the Trump Administration will take health care and its likely impact on long-term care (LTC). It is especially interesting to note that the primary reason this version did not reach Congress for a vote was that the most conservative side of the Republican party did not believe this bill went far enough in its repeal of Obamacare; as such, the eventual bill passed may be even more severe in its impact on LTC in the direction outlined in this article.

The AHCA attempted to utilize a free market while providing a safety net to the 28 million people still without insurance and the almost 30 million people who received insurance under Obamacare. Current projections from the Congressional Budget Office reported that a significant decrease in insurance coverage would result from Medicaid expansion funding no longer available under AHCA. Indeed, the total number of uninsured was estimated to reach 24 million people by 2026—14 million less people insured under Medicaid, 3 million less from the health insurance marketplace, and 7 million less under employer-sponsored plans.2 This would reduce the number of dual-eligible beneficiaries as the uninsured applied for Medicare.

Given that 51 million older adults are covered under Medicare and 9 million older adults are also covered by Medicaid—which is the major source of funding for LTC—the question would have become how will the AHCA’s proposed health care changes impact these populations, especially those needing LTC.

If the bill had made it to Congress, the probable impact of the AHCA on older adults could have been expected in three primary areas. These include the health of those as they enter Medicare, coverage for LTC services through Medicaid, and assistance with the social determinants of health.

Entering Medicare Sicker

One unintended consequence of the AHCA is that it could have resulted in pre-Medicare older adults delaying health maintenance such as preventive services or caring for chronic comorbid conditions. This comes as a result of the AHCA phasing out existing expansion of the Medicaid program for ages 55 to 64 who cannot afford coverage. This is doubly problematic as insurance for this group is becoming more expensive due to the eradication of premium cost protections, which allow premium ratios to increase premiums by several thousand dollars for older adults. With more expensive coverage and less access to Medicaid, these older adults are likely to enter Medicare sicker from putting-off proper care. Geriatric care providers would be well served to take full advantage of the “Welcome to Medicare” physical exam to develop a comprehensive care plan for all new Medicare beneficiaries, especially in light of the fact that some may be entering the Medicare program after previously only having limited coverage.

Fewer Individuals Able to Pay for LTC

Another change within the AHCA would have impacted Medicaid by capping federal financial support to the states through application of a limit and preset amount per person, which would result in a drop of 14 million individuals currently obtaining coverage through Medicaid.2 These individuals would find it difficult to not only pay for skilled nursing facility (SNF) care but also care at other sites such as assisted living (AL) communities or home-based long-term services. Medicaid is one of the only health care insurances that covers supportive housing such as those available through SNFs, AL communities, and medical group homes. Without this support, older adults may fall into substandard housing with no supportive services, resulting in overutilization of hospital and other health care resources paid by Medicare and others. Developing alternative approaches to support these older adults through other housing options or support such as day care and home-based services could be a substitute for Medicaid paying for supportive housing.

Reduction in Support for Social Determinants of Health

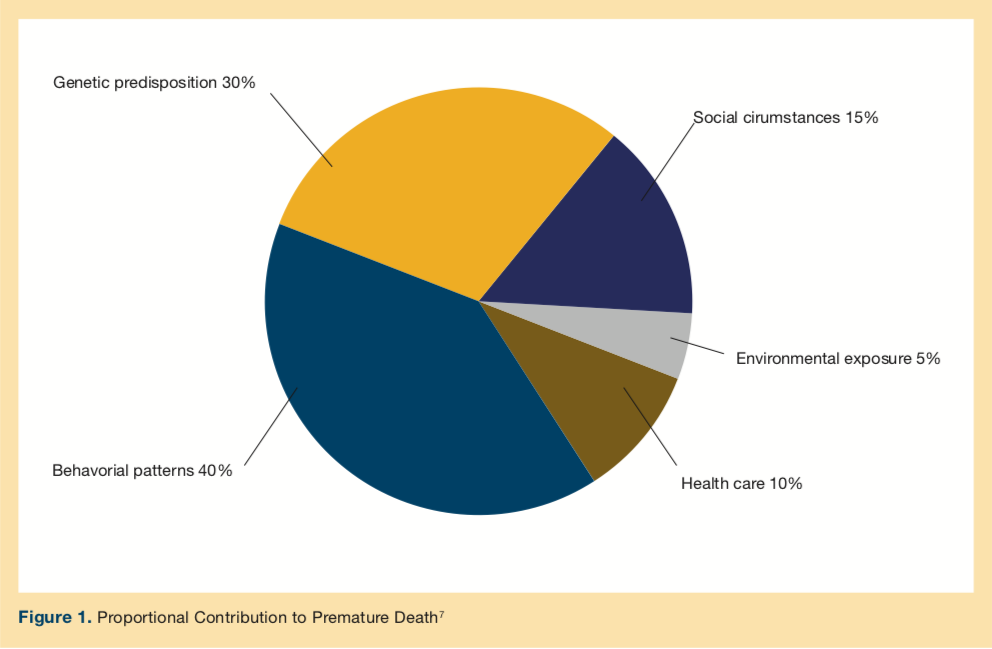

Like housing, there are other social determinants of health that have a significant impact on improving health and reducing health care expenditures. Social determinants of health are described as “the structural determinants and conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age.”3 They include factors like socioeconomic status, education, physical environment, employment, and social support networks. Despite annual health care expenditures projected to exceed $3 trillion, health outcomes in the United States continue to fall behind other developed countries.4 Recent analysis shows that, although overall spending on social services and health care in the United States is comparable to other Western countries, the United States disproportionately spends less on social services and more on health care.5 Although health care is essential to health, research demonstrates that it is a relatively weak health determinant compared with the social determinants of health.6 And while health care is said to contribute about 10% to the risk of premature death, social and environmental factors have twice that level of impact (Figure 1).7

However, the US investment in the social determinants of health is far less than those made by other countries; in fact, other developed nations do a far better job of preventing their vulnerable populations from suffering serious illness by investing substantially more in social services that impact health. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) nations, on average, spent about $2 on social services for every dollar of health care spending, compared with only about 55 cents per dollar in the United States, according to a study of 2009 data by Elizabeth Bradley of Yale University and Lauren Taylor of Harvard University.8 After factoring in these expenditures, the United States is pushed down to 13th among OECD countries in total health care outlays.8

The growing belief in the importance of social determinants of health has been increasingly demonstrated by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Indeed, in recent policies and statements, CMS has embraced an “upstreamist” view of improving health outcomes for socially disadvantaged populations.9 For example, in this fiscal year, CMS began risk-adjusting10 the Medicare Advantage (MA) Star Rating incentive program for differences in dual eligibility and disability status among beneficiaries in various MA Plus insurance plans. In addition, several CMS officials are on record supporting the concept of more effective risk adjustment. Director Cara James, PhD, who runs the CMS Office of Minority Health, recently said in an interview11 that as much as 80% of health disparities are driven by social determinants of health and that structural barriers prevent the health care system from addressing these conditions effectively.

Despite the importance and cost benefits of investing in social determinants of health, the AHCA decreased these investments from a federal standpoint. One example is the proposed repeal of the Prevention and Public Health Fund,1 which was established to provide funding for key public health programs that improve the health and safety of all Americans through disease prevention initiatives, immunizations, and health screenings, and has provided support for older adults with chronic conditions. Aid for older adults included support for evidence-based falls prevention programs that have benefitted more than 30,000 older Americans and adults with disabilities since 2014.12

President and CEO of the Mount Sinai Health System, Kenneth Davis, MD, has commented8 on the complex issue of health care spending:

“To ease the strain of the high cost of medicine, the United States must sew a tighter social safety net. Enhancing health counseling, expanding nutritional programs, increasing the availability of quality affordable housing, and engaging more caseworkers in patient outreach all can have societal impact beyond the immediate benefit to recipients. This kind of smart spending on social services that maintains the well-being of our population is a path to achieving our goal of a healthier nation that spends less overall on health care.”

In the end, there would have certainly been reductions in direct federal spending, thus, it is important to harness the power of States, communities, families, and providers to promote not only access to health care but also, and more importantly, to investment in social determinants of health, such that the overall clinical and financial outcomes for older adults can be improved.

1. American Health Care Reform Act of 2017, HR 277, 115th Cong (2017). https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/277/text. Accessed March 17, 2017.

2. Congressional Budget Office. American Health Care Act. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/hr1628.pdf. Published March 13, 2017. Updated March 23, 2017. Accessed March 24, 2017.

3. Heinman HJ, Artiga S. Beyond health care: the role of social determinants in promoting health and health equity. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2015. http://kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/. Accessed March 24, 2017.

4. Squires D, Anderson C. US health care from a global perspective: spending use of services, prices, and health in 13 countries. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2015;15:1-15.

5. Bradley EH, Taylor LA. The American Health Care Paradox Why Spending More is Getting Us Less. New York, NY: Public Affairs; 2013.

6. McGinnis JM, Foege WH. Actual causes of death in the US. JAMA. 1993;270(18):2207-2212.

7. McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. HealthAffairs (Millwood). 2002;21:78-93.

8. Davis K. To lower the cost of health care, invest in social services. Health Affairs Blog. July 14, 2015. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/07/14/to-lower-the-cost-of-health-care-invest-in-social-services/. Accessed March 20, 2017.

9. Manchanda R. What makes us get sick? Look upstream. TEDSalon NY2014. TED.com website. https://www.ted.com/talks/rishi_manchanda_what_makes_us_get_sick_look_upstream?language=en. Filmed August 2014. Accessed March 23, 2017.

10. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Announcement of Calendar Year (CY) 2017 Medicare Advantage Capitation Rates and Medicare Advantage and Part D Payment Policies and Final Call Letter. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Downloads/Announcement2017.pdf. Published April 4, 2016. Accessed March 23, 2017.

11. Q&A: Building the business case for achieving health equity. Modern Healthcare. April 23, 2016. modernhealthcare.com/article/20160423/PODCAST/304239941. Accessed March 23, 2017.

12. Kulinski K, DiCocco C, Skowronski S, Sprowls P. Advancing community-based falls prevention programs for older adults—the work of the Administration for Community Living/Administration on Aging. Front Public Health. 2017;5:4.