Honoring Nursing Home Resident Preferences for Recreational Activities to Advance Person-Centered Care

Nursing homes are embracing person-centered care, an approach that emphasizes “knowing the person” and honoring each individual’s preferences. As providers shift toward person-centered care, they need timely, efficient tools and methods to gauge whether they are meeting consumer preferences and to identify areas in need of improvement. The Preference Match Tracker is a new tool that measures alignment between resident preferences and recreational activities. The Preference Match Tracker can be used to document and track individual recreation preferences and activities and then produce practical, graphic reports about these preferences for each resident, for each household within the facility, and for the facility as a whole. The authors describe the development of the tool and the outcomes of a pilot test of the tool in a long-term care facility. The Preference Match Tracker provides information that recreation staff can easily interpret and use to enhance the quality of care and quality of life for NH residents.

Key words: older adults, nursing homes, preferences, person-centered care, quality improvement, recreation

Nationally, nursing homes (NHs) are shifting toward a person-centered philosophy of care, in which staff understand each resident’s preferences, goals, and values and seek to honor them throughout the care delivery process. Consensus is growing among key stakeholders—government, provider groups, and consumers—that person-centered care (PCC) is an important component of care quality.1-7

PCC customizes care processes to fit the unique needs and preferences of each resident.8 The literature has strongly supported the beneficial effects on health and psychological well-being associated with tailoring care in NHs.9-13 Most recently, the focus has shifted to developing tools that enable long-term care (LTC) providers to efficiently customize care. One approach is to measure residents’ preferences for care delivery. This strategy honors the experiences of individuals and the continuity of likes and dislikes that they have developed over a lifetime.14 It also empowers residents by acknowledging their preferences in the context of their strengths and needs, which helps them to maximize their potential for retaining relationships, capabilities, interests, and skills.15

Recreational activities in NHs are one of the most important determinants of a resident’s quality of life and well-being.16,17 Carefully tailored activities can provide a needed source of meaning, competence, social connection, and pleasure for residents living with disability.18 The first step in customizing activities is to understand a person’s recreational preferences. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0 requires all NHs to assess each resident’s preferences for eight recreational activities (Section F: Preferences for Customary Routines and Activities).19 The information is useful for individual care planning; however, the MDS 3.0 does not explore whether a person’s preferences have been fulfilled.

The Pleasant Events Schedule20 is an instrument that asks NH residents to report their enjoyment of 30 activities. Residents are also asked to report on their participation in enjoyable activities during the past month. When the tool was embedded in a clinical intervention to systematically assess and increase NH residents’ pleasant experiences, results showed clinically significant reductions in depressive symptoms and improved psychiatric functioning.21

The Preferences for Everyday Living Inventory (PELI)22 is another tool that assesses recreational preferences among older adults. Originally developed for older adults receiving home care services, the tool was later adapted for use with NH residents. The 72-item Preferences for Everyday Living Inventory–Nursing Home version© (PELI-NH©) assesses specific preferences across a wide range of life domains, including activities. The tool provides valuable information for planning preference-based care and has been validated through research studies. A 2014 study examined the consistency of NH residents’ ratings of everyday preferences over 1 week with PELI-NH and found that personal care preferences were more stable, whereas preferences for leisure activities were less stable. Overall, NH residents had a mean exact agreement of 65.9% on all PELI-NH items when using a Likert scale with responses ranging from 1 to 4. When a dichotomous scale (“Important” or “Not Important”) was used, the level of agreement rose to 87.3%.23

In 2013, the Advancing Excellence in America’s Nursing Homes Campaign, a national quality improvement (QI) collaborative, pilot-tested the Advancing Excellence in America’s Nursing Homes (AE) Person-Centered Care Tool, a toolkit to capture information about NH residents’ preferences, as well as to track their satisfaction with the way their preferences were being fulfilled.6 Aspects of the PELI-NH were incorporated into the toolkit. The toolkit consists of interview materials regarding 16 personal care and activity preferences from the MDS, plus follow-up questions that ask residents how satisfied they are with fulfillment of important preferences, and an easy-to-use Excel spreadsheet that calculates graphic displays of quality measures of preference congruence (the degree to which NHs are able to fulfill recreational pursuits most preferred by their residents) and care conference attendance. In a 12-site pilot test, NHs gave the AE Person-Centered Care Tracking Tool strong positive ratings, indicating that it was easy to use and helped them to identify opportunities to improve PCC.6

Providers need valid and efficient tools to support their ability to provide PCC and improve daily quality of life for residents. Building on the AE Person-Centered Care Tracking Tool, our team created the Preference Match Tracker, a tool that is designed to help NHs measure, deliver, and improve the quality of preference-based recreational activities, a vital part of PCC. The Preference Match Tracker is constructed by documenting residents’ preferences and by using data from electronic medical records (EMR) to track the provision of recreational activities that align with those preferences. We report on the development of the Preference Match Tracker, its pilot testing in a sample of 205 NH residents, and the tool’s feasibility of use. Using the Preference Match Tracker can strengthen a facility’s ability to gauge how well it honors residents’ recreational preferences and pinpoint areas for QI.

Methods

The Preference Match Tracker, a recreation quality indicator that can assess residents’ activity preferences and measure objectively how often preferences are met, was developed using a community-based participatory research model;24 research, recreation, and quality assurance staff from a large nonprofit NH convened monthly to develop the quality indicator, and NH residents and information technology personnel were closely involved in the project. The Institutional Review Board approved this QI project for the participating center (Preference Congruence Quality Indicator Reporting, Protocol #031201).

Participants and Setting

To demonstrate the feasibility of the Preference Match Tracker indicator, quality improvement data were collected from 270 residents in a single, large, skilled nursing facility during a 6-month period (September 2012 to February 2013). Eligible individuals resided in the facility for 6 consecutive months during the study period. Forty-eight individuals were excluded from the sample due to death or transfer to another facility.

The Global Deterioration Scale (GDS)25 was used to assess the functional capabilities of each resident in order to provide a general guideline for tailoring activities and optimizing the resident’s ability to participate (ie, taking a strengths-based approach).26 The GDS was selected because it was already used consistently across the facility and because it provided more clinically relevant information about resident functioning than other routine measures, such as the Mini-Mental Status Examination. Under the clinical leadership of a Certified Therapeutic Recreation Specialist, recreation staff assigned GDS scores based on their clinical assessment of each resident’s level of cognitive and functional ability as it related to recreational pursuits. Residents who exhibited mild symptoms of dementia, but were mostly capable of participating in recreation programs with limited assistance, received a score of 3 or 4. Individuals who exhibited moderate signs of dementia and who required an increased level of assistance, such as verbal or physical cueing, to engage in activities received a score of 5. Residents who exhibited severe symptoms of dementia and required extensive assistance or 1:1 stimulation to elicit engagement in recreation programming received a score of 6 or 7. Residents were not excluded based on level of cognitive or functional ability.

Resident Activity Preferences Questionnaire

The PELI-NH was chosen to gather information about NH residents’ preferences because of its demonstrated content validity and flexibility for use in NHs.22 During its initial test in a large-scale sample of home care clients, PELI-NH was found to have construct validity as well as to identify older adults’ most strongly held preferences across domains.22

The PELI-NH has a total of 72 items and requires 30–45 minutes to administer. A subset of 28 PELI-NH items that pertain to recreational pursuits was used as the basis of an activity preference questionnaire.22 After careful review, five of these items were eliminated because staff could not easily document a resident’s participation in them (eg, watching others do activities, listening to the radio). Thus, a total of 23 items were included in the final questionnaire, eight of which were identical to the CMS-mandated Minimum Data Set 3.0 for NHs under Section F: Preferences for Customary Routines and Activities.19,27

In a subsequent phase, researchers used cognitive interviewing techniques to refine the tool for NH residents. Cognitive interviewing allows researchers to explore the language and meaning of questions and to revise a measurement tool for use with varying respondent groups. To refine the PELI, questions were examined to identify possible problems in wording – for example, through observing respondents’ hesitation or difficulty in remembering or understanding items; discordance between responses to probes and item ratings; and difficulty responding with specific examples to probes. Residents’ responses guided substantial revisions of the questionnaire items to better include language that NH residents use and understand, thereby reducing potential measurement error and ensuring that everyday preferences assessed are relevant to NH residents.28

To ask residents about their preferences, the questionnaire uses the stem, “While you are at this facility, how important is it to…[insert specific preference].” Residents respond using a Likert scale from 1 (“Very important”) to 4 (“Not important at all”). They also can indicate that a preference is “Important, but can’t do” if they feel that they are unable to do the preferred activity or that they are not provided the option of doing it at their facility. The final questionnaire used in this study is available upon request from the authors.

Most residents (n = 194) completed the questionnaire themselves via interview. Staff or family proxies completed the questionnaire for residents who were unable to respond on their own due to level of cognitive impairment (n = 11). Seventeen individuals were excluded because they could not provide self-report nor could a proxy respondent be found. All questionnaire responses were stored in the residents’ EMRs.

Nursing Home Recreational Activity Inventory

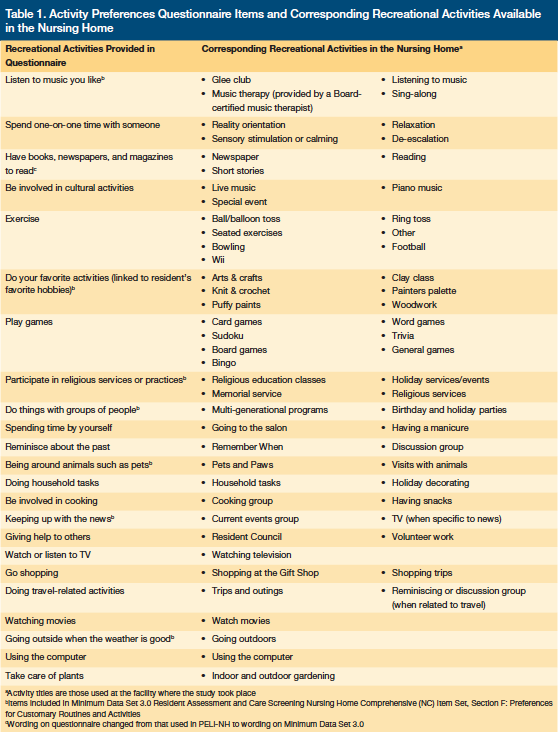

In order to track how well the care delivered matched an individual’s preferences, an inventory of activities offered by the facility was created, and each activity was aligned with the recreational preference items (eg, bowling was assigned to the exercise preference category). The 23 items included in the activity preference questionnaire and the recreational activities that correspond to each of these items are presented in Table 1.

Activity Attendance Tracking

To capture information about residents’ activity attendance, recreation therapists created descriptions for each activity. Recreation and research staff engaged in three meetings to develop uniform standards and promote buy-in for accurately documenting activity attendance. Professional and paraprofessional staff (three certified therapeutic recreation specialists, two music therapists, six recreation assistants, and 10 volunteers) recorded daily resident attendance at activities in the EMR. Attendance data were gathered over the 6-month study period.

Activity Preference and Attendance Matching

The Preference Match Tracker consisted of a Microsoft Access database program designed to calculate the congruence between resident activity preferences and resident activity attendance. Activity preference data and activity attendance data were pulled from each resident’s EMR to calculate congruence scores. The calculation included only preferences that residents rated as “Very important,” “Somewhat important,” or “Important, but can’t do.” An activity was considered to be congruent, or “matched,” if the resident participated in the activity at least twice in a 1-month period. The scores were calculated at three levels: the individual resident, the household (an NH unit with 27 residents), and the facility as a whole.

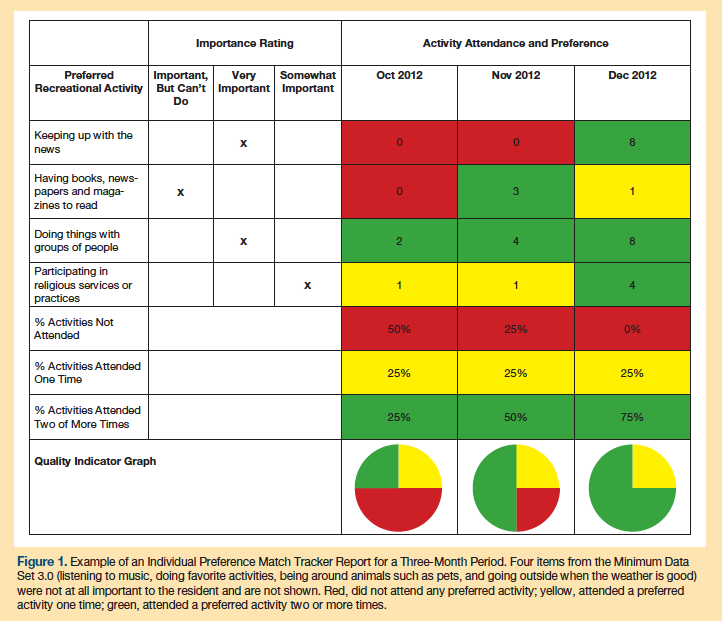

Each month, Preference Match Tracker scores were calculated for each resident, each household, and the facility, and color-coded reports were created to provide a visual display of the data for programming and planning purposes. Individual reports compared a resident’s attendance at activities with his/her preferences, providing information to gauge how well a specific resident’s recreational activity preferences were being met and pointing to priorities for improvement. Individual reports listed summary scores to show the percentage of preferred activities that a resident attended twice or more, once, or not at all during the month. Activities rated as important by the resident that had not been attended were colored in red; those that had been attended once were colored in yellow; those that had been attended twice or more per month were colored in green.

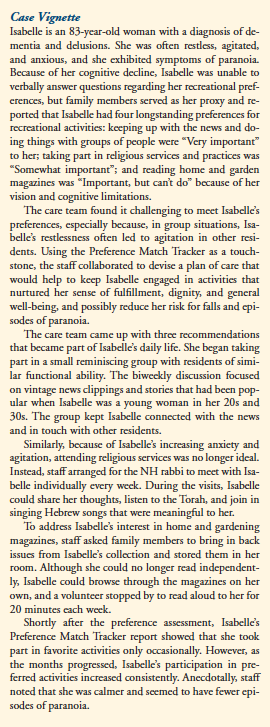

Household reports allowed staff to examine how well activity offerings matched preferences for a group of 27 residents living together on a unit. Household preference congruence scores represent the average monthly preference congruence score (ie, percentage of times that a resident attended important activities twice or more) for all 27 individuals residing on the unit for a given month.

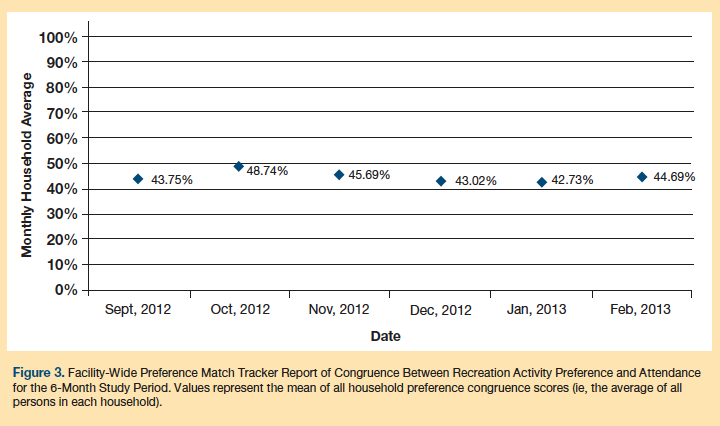

Facility reports show trends in the facility-wide recreational preference congruence score. The means of all household preference congruence scores (which are the average of all persons in each household) for each month over a 6-month period are presented in a graph showing trends in the mean congruence scores for all residents in the facility.

Results

Findings are reported for 205 residents who had complete data for a 6-month period and for whom the activity preference questionnaire was completed and activity attendance was tracked. The sampled population was 81.0% female and had a mean (sd) age of 87.8 (8.9) years. Most participants were widowed (71.7%). Nearly half of the residents (47.3%) were functionally impaired, with scores of 5–7 on the Global Deterioration Scale.

Pilot examination of the Preference Match Tracker found that the color-coded individual reports allowed staff to easily scan for areas of congruence (green) and areas requiring attention (yellow and red), enabling them to quickly spot gaps in alignment between activities and pinpoint preferences that were not being fully met. This prompted conversation with the resident about ways to improve the match and prompted staff to develop new approaches to designing and delivering recreational programs that better matched resident wishes. Sometimes this meant adding new activities. As new activities are offered, staff can review Preference Match Tracker data and evaluate whether residents attend their preferred activities. In other cases, staff developed creative strategies to engage residents or adapt activities to individual functional ability. When red or yellow appears on a report, staff cycle back to the assessment and planning process and determine how to provide activities or resources that better fulfill resident desires.

The example in Figure 1 shows a 3-month report for a resident (see Case Vignette) who rated one activity as “Important, but can’t do.” For activities coded as “Important, but can’t do,” staff developed strategies to meet the preference in ways that matched the resident’s cognitive and functional abilities. The goal was to preserve the genuine nature of the activity to the extent possible, in line with a resident’s current skill set. For example, a resident with a low GDS score might meet her preference for cooking by preparing a meal with others; a resident with the same preference, but a high GDS score, might achieve her preference by smelling the aromas of food simmering in the kitchen or by reminiscing about baking with a staff member or volunteer. Research staff kept records of barriers and their solutions as they emerged in the community-based participatory process.

Figure 2 shows an example of one household’s Preference Match Tracker scores for the eight recreation items from the MDS 3.0. Household reports allow management, recreation coordinators, and line staff to readily identify priorities for improvement across the facility. Staff can design preference-based activities in a variety of formats—for groups, for one-to-one staff and resident interaction, or for residents’ independent pursuits. For example, if “being around pets” has low congruence for several members of the household, staff might add a pet therapy group to the weekly plan or encourage residents to visit independently with the facility’s live-in pets. Programs demonstrating a high level of congruence for residents in a household (eg, residents are attending preferred activities), such as “listening to music you like,” might need no adjustment.

The facility report shows how well the entire facility is honoring resident recreational preferences (Figure 3). From a QI perspective, the facility report is useful for benchmarking and quality assurance performance improvement (QAPI) efforts, documenting how the organization advances its overall efforts of delivering preference-based care. It draws attention to any downward trends, and can trigger a Plan, Do, Study, Act cycle, where staff conduct a root cause analysis to understand current practices and devise new strategies to enhance preference fulfillment. At this highest level of measurement, the facility can keep an eye on the “organizational health” of person-centered care for all households that comprise a community of care. The solutions might be simple—for example, providing supplies that will meet resident activity preferences—or they may be more complex, such as re-training employees in techniques to provide recreation activities in line with resident abilities. This system can provide an opportunity to clearly identify areas of need as well as increase overall competence of the PCC team.

Case Vignette

Isabelle is an 83-year-old woman with a diagnosis of dementia and delusions. She was often restless, agitated, and anxious, and she exhibited symptoms of paranoia. Because of her cognitive decline, Isabelle was unable to verbally answer questions regarding her recreational preferences, but family members served as her proxy and reported that Isabelle had four longstanding preferences for recreational activities: keeping up with the news and doing things with groups of people were “Very important” to her; taking part in religious services and practices was “Somewhat important”; and reading home and garden magazines was “Important, but can’t do” because of her vision and cognitive limitations.

The care team found it challenging to meet Isabelle’s preferences, especially because, in group situations, Isabelle’s restlessness often led to agitation in other residents. Using the Preference Match Tracker as a touchstone, the staff collaborated to devise a plan of care that would help to keep Isabelle engaged in activities that nurtured her sense of fulfillment, dignity, and general well-being, and possibly reduce her risk for falls and episodes of paranoia.

The care team came up with three recommendations that became part of Isabelle’s daily life. She began taking part in a small reminiscing group with residents of similar functional ability. The biweekly discussion focused on vintage news clippings and stories that had been popular when Isabelle was a young woman in her 20s and 30s. The group kept Isabelle connected with the news and in touch with other residents.

Similarly, because of Isabelle’s increasing anxiety and agitation, attending religious services was no longer ideal. Instead, staff arranged for the NH rabbi to meet with Isabelle individually every week. During the visits, Isabelle could share her thoughts, listen to the Torah, and join in singing Hebrew songs that were meaningful to her.

To address Isabelle’s interest in home and gardening magazines, staff asked family members to bring in back issues from Isabelle’s collection and stored them in her room. Although she could no longer read independently, Isabelle could browse through the magazines on her own, and a volunteer stopped by to read aloud to her for 20 minutes each week.

Shortly after the preference assessment, Isabelle’s Preference Match Tracker report showed that she took part in favorite activities only occasionally. However, as the months progressed, Isabelle’s participation in preferred activities increased consistently. Anecdotally, staff noted that she was calmer and seemed to have fewer episodes of paranoia.

Discussion

While there is growing consensus about the importance of providing PCC tailored to residents’ needs and preferences, NHs lack techniques to objectively assess this care for QI purposes. The Preference Match Tracker provides a tool that endeavors to measure residents’ important recreational preferences and fulfillment of those preferences. The reporting process empowered staff to improve care delivery on individual, household, and facility levels. Staff could review the data, brainstorm why congruence may have been low, generate approaches to improve preference matching, and later evaluate how well new strategies were working. The reports provided staff with a visual representation of resident participation in the life of the facility, how well residents’ preferences were being met, and what areas of importance should be incorporated into care plans.

One advantage of an objective quality indicator such as the Preference Match Tracker is to increase access to information regarding all NH residents. Often, self-report measures exclude individuals with severe cognitive impairment in the denominator of the quality indicator; however, this performance-based measure allows all NH residents to be included, using proxy reports by staff or family members when needed.

The Preference Match Tracker provides proof of concept in the feasibility of measuring recreational preference congruence. But, while it provides a tracking mechanism for improving PCC in NHs, development of this tool also highlighted person–environment barriers and facilitators of providing preference-based care that can inform usage moving forward. As expected, the study showed that health and functional status may impede a resident’s ability to participate in activities (ie, visual and hearing impairment, not feeling well, pain, etc.) and that adaptations will be needed.29

Competition for fulfillment of other needs or preferences also may be a barrier; for example, medical appointments, therapy, and family visits often take precedence over recreational pursuits. While these are high priorities, it is possible that tracking congruence will prompt facilities to find new ways to assure that recreational programming is a consistent part of daily resident life. This is particularly important because recreation tailored to resident needs, and integrated into the facility schedule, has been shown to reduce residents’ level of agitation and need for psychoactive medications.18,30

Facility or environmental barriers may be present as well, such as when a preferred activity is not offered (eg, pet therapy). Also, activities often are planned for more popular preferences (eg, listening to music), making less common preferences (eg, doing household tasks) harder to fulfill. Additional barriers are that residents may not like or be satisfied with the type of activity offered and may, therefore, stop attending. Also, some activities are seasonal in nature.

Several areas need further development prior to widespread use of the Preference Match Tracker. It is difficult for staff to document all activities. For example, trips to a gift shop, household tasks such as tidying up, volunteer work, and spontaneous time spent with household pets are activities that may go undocumented if unobserved by staff. Also, cognitively capable residents can engage in preferred activities independently without staff facilitating or observing. Finally, staff may forget to document resident refusals to participate in activities; this leaves a gap in understanding regarding unattended activities that may be important to a resident.

Another open question pertains to the standard for deeming that a preference has been met. In this study, we considered a preference met if a resident attended the activity at least twice per month. The cutoff of two times per month was chosen for this pilot evaluation as a starting point for tracking; however, we recognize that this benchmark should be refined over time. Ideally, the standard should be individualized for each person and for each given preference. Whereas some preferences may be fully satisfied when they occur at this rate (eg, shopping), others (eg, listening to music) may require greater frequency to reach congruence. Furthermore, one resident might prefer to shop once a month and keep up with the news every day, while another might want to shop weekly and check the news only occasionally.

Similarly, our facility-level categorization of congruence equaling at least 50% congruence between activity preference and activity attendance is somewhat arbitrary. Lacking an established benchmark, we selected what seemed to be a clinically acceptable and realistic standard for having preferences met in a residential living environment. Further work should gauge whether this is an appropriate standard, as well as test how to tailor the Preference Match Tracker to align attendance with the number of times an individual wishes to attend. Such an adjustment would maximize satisfaction and ensure that care fully meets residents’ preferences.

In addition, if a resident seems disinterested in participating in a previously held important preference, this may signal the need to re-administer the activity preference questionnaire. In related work, NH residents’ recreational preferences changed in relation to personal or environmental circumstances more frequently than preferences for personal care and other aspects of daily life.23,29

Finally, proxy responders reporting the preferences of residents who are unable to self-report have been found to be highly variable in their accuracy.31-33 Additional studies are needed to assess ways to improve the accuracy of proxy reports, particularly for NH residents with cognitive impairment who cannot verbalize their preferences.

Conclusion

The Preference Match Tracker allows providers to see “at a glance” whether they are succeeding in providing recreational activities that are person-centered. The Preference Match Tracker provides information that recreation staff can easily interpret and use to enhance the quality of care and quality of life for both cognitively capable and impaired NH residents. The easy-to-read reports provide the impetus to prompt staff to reevaluate the types and effectiveness of provided recreation and to discover new approaches more in line with residents’ needs and personal preferences. Use of the Preference Match Tracker can lead to improved preference fulfillment and provide a way to benchmark PCC efforts within and across facilities.

1. Center for Excellence in Assisted Living. Person-centered care in assisted living: An informational guide. http://www.leadingageok.org/Person-Centered%20Care%20in%20Assisted%20Living%20An%20Informational%20Guide.pdf. Published June 2010. Accessed January 2, 2016.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Long-Term Care Reform Plan. http://www.cms.gov/medicaidgeninfo/downloads/ltcreformplan2006.pdf. Published September 28, 2006. Accessed January 2, 2016.

3. Home Health Quality Initiative. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/homehealthqualityinits/. Updated June 26, 2015. Accessed January 2, 2016.

4. Kietzman, KG. Using a “person-centered” approach to improve care coordination: opportunities emerging from the Affordable Care Act. J Geriatr Care Manage. 2012;22(2):13-19.

5. Koren, MJ. Person-centered care for nursing home residents: The culture-change movement. Health Aff. 2010; 29(2):312-317.

6. Van Haitsma K, Crespy S, Humes S, et al. New toolkit to measure quality of person-centered care: development and pilot evaluation with nursing home communities. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(9):671–680.

7. Advancing Excellence in America’s Nursing Homes. Person-Centered Care: Follow These Seven Simple Steps to Success. Advancing Excellence website. https://www.nhqualitycampaign.org/goalDetail.aspx?g=pcc#. Accessed January 6, 2016.

8. Edvardsson D, Varrailhon P, Edvardsson K. Promoting person-centeredness in long-term care: an exploratory study. J Gerontol Nurs. 2014;40(4):46-53.

9. Cvengros JA, Christensen AJ, Cunningham C, Hillis SL, Kaboli PJ. Patient preference for and reports of provider behavior: Impact of symmetry on patient outcomes. Health Psychol. 2009;28(6):660-667.

10. Jahng KH, Martin LR, Golin CE, DiMatteo MR. Preferences for medical collaboration: patient-physician congruence and patient outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57(3):308-314.

11. Kasser V, Ryan RM. The relation of psychological needs for autonomy and relatedness to vitality, well-being and mortality in a nursing home. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1999;29(5):935-954.

12. Vallerand RJ, O’Connor BP. Motivation in the elderly: a theoretical framework and some promising findings. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne. 1989;30(3):538-550.

13. Elliot A, Cohen LW, Reed D, Nolet K, Zimmerman S. A “recipe for culture change? Findings from the THRIVE survey of culture change adopters. Gerontologist. 2014;54 (suppl 1):S17-S24.

14. Brooker D. Person-Centered Dementia Care: Making Services Better. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley, 2006.

15. Menne HL, Johnson JD, Whitlatch CJ, Schwartz SM. Activity preferences of persons with dementia. Activities, Adaptation Aging. 2012;36(3):195-213.

16. Havighurst RJ. Successful aging. In: Williams RH, Tibbitts C, Donohue W, eds. Processes of Aging: Social and Psychological Perspectives. Vol 1. New York, NY: Atherton; 1963:299-320.

17. Port A, Barrett VW, Gurland BJ, Perez M, Riti F. Engaging nursing home residents in meaningful activities. Annals of Long-Term Care. 2011;19(12). www.annalsoflongtermcare.com/article/engaging-nursing-home-residents-meaningful-activities. Accessed January 2, 2016.

18. Morley JE, Philpot CD, Gill D, Berg-Weger M. Meaningful activities in the nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(2):79-81.

19. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Minimum Data Set (MDS) – Version 3.0. Resident assessment and care screening. Nursing Home Comprehensive (NC) Item Set. CMS website. Accessed January 2, 2016.

20. Meek S, Shah SN, Ramsey SK. The Pleasant Events Schedule nursing home version: A useful tool for behavioral interventions in long-term care. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(3):445-455.

21. Meeks S, Van Haitsma K, Schoenbachler B, Looney SW. BE-ACTIV for depression in nursing homes: primary outcomes of a randomized clinical trial. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2015;70(1):13-23.

22. Van Haitsma K, Curyto K, Spector A, et al. The preferences for everyday living inventory: scale development and description of psychosocial preferences responses in community-dwelling elders. Gerontologist. 2013;53(4):582-595.

23. Van Haitsma K, Abbott KM, Heid AR, et al. The consistency of self-reported preferences for everyday living: implications for person-centered care delivery. J Gerontol Nurs. 2014;40(10):34-46.

24. Minkler M, Wallerstein N, eds. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 2010.

25. Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(9):1136-1139.

26. Anderson L, Heyne L. A Strengths Approach to Assessment in Therapeutic Recreation: Tools for Positive Change. Ther Recreation J. 2013;46(2):89-108.

27. Housen P, Shannon GR, Simon B, et al. Why not just ask the resident? J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(11):40-49.

28. Curyto K, Van Haitsma KS, Towsley GL. Cognitive interviewing: revising the preferences for everyday living inventory for use in the nursing home. Res in Gerontol Nurs. 2016;9(1):24-34.

29. Heid AR, Eshraghi K, Duntzee C, Abbott K, Curyto K, Van Haitmsa K. ‘It Depends’: Reasons Why Nursing Home Residents Change their Minds about Care Preferences. Gerontologist. 2014. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu040.

30. Buettner LL, Ferrario J. Therapeutic recreation-nursing team: A therapeutic intervention for nursing home residents with dementia. Annu Ther Recreation. 1997;7:21-28.

31. Carpenter BD, Lee M, Ruckdeschel K, Van Haitsma KS, Feldman PH. Adult children as informants about parent’s psychosocial preferences. Fam Relations. 2006;55(5):552–563.

32. Reamy AM, Kim K, Zarit SH, Whitlatch CJ. Understanding discrepancy in perceptions of values: Individuals with mild to moderate dementia and their family caregivers. Gerontologist. 2011; 51(4):473-483.

33. Whitlatch CJ, Piiparinen R, Feinberg LF. How well do family caregivers know their relatives’ care values and preferences? Dementia. 2009;8(2):223-243.