Helping Families in Long-Term Care Facing Complex Decisions: Applying the Evidence about Family Meetings from Other Settings

In the long-term care (LTC) setting, communication between the healthcare team, residents, and families occurs in formal and informal ways. Elements and outcomes of family meetings, which represent a structured communication process, have been studied primarily in intensive care units (ICUs) and palliative care settings. The complexity of medical needs, frequency of reliance on surrogate decision-makers, and prognostic uncertainty of patients in these settings are similar to those encountered in LTC for residents who are experiencing acute changes in health status requiring treatment decisions to be made. Research findings, expert opinion, and consensus-based guidelines have outlined strategies that can be used to support effective communication in conducting a family meeting. This article describes three strategies that may be used in settings in which family meetings frequently occur, reviewing the optimal timing for a family meeting, use of a step-by-step process as a format for conducting a family meeting, and communication techniques that acknowledge emotions and facilitate shared decision making. These strategies may be helpful for clinicians in LTC, as documenting resident goals and translating these goals to the plan of care are critical to ensuring proper resident and family-centered care.

A repetitive cycle of patient transfer between the long-term care (LTC) facility and the acute care hospital is common among residents with chronic life-limiting diseases such as dementia and end-stage organ failure. Poorly discussed and documented patient or surrogate decision-maker–centered goals of care are a common etiology leading to this phenomenon. The growth of inpatient and outpatient palliative care programs has affirmed the critical need for more in depth discussions of patient values, goals, and end-of-life preferences in all healthcare settings.1 In the LTC setting, where residents may experience a gradual or sudden mental or physical decline, leading to a lack of decision-making capability, discussions of patient values, goals, and preferences typically occur at the family meeting, which may at some institutions be referred to as the family care conference or the care conference. A family meeting should be conducted for clinically complex cases or when there is a change in clinical status to ensure that medical treatment plans remain consistent with resident goals.

Family meetings in LTC can be divided into two types: (1) meetings to discuss current health status and future planning during periods of health stability (eg, care conference shortly after admission); and (2) meetings to make definitive medical care treatment decisions during times of health instability (eg, functional decline, frequent hospital admissions), which is the primary focus of this article. The National Quality Forum (NQF) identified 38 preferred practices to define quality palliative care for patients with advanced illness, one of which is to “conduct regular patient and family care conferences with physicians and other appropriate members of the interdisciplinary team to provide information; to discuss goals of care, disease prognosis, and advance care planning; and to offer support.”2 This article describes strategies for conducting effective family meetings in LTC for patients with advanced illness that meet the spirit of the NQF preferred practices for palliative and hospice care, reviewing the timing of the family meeting, use of a process approach, and communication strategies that can address conflict and support decision making.

The Family Meeting

During the family meeting, clinicians share information, discuss prognosis, and plan for current and future decisions about medical treatments. A primary end point for a family meeting is improvement in resident outcomes, which can be achieved when a forum for communication among the resident, family, and healthcare team is established. In addition, effective family meetings lead to resident and family satisfaction and the development of a plan of care that is consistent with resident and family goals and values. There is a small body of literature about the structure and process of conducting effective family meetings,3-10 with the majority of research conducted in the critical care setting, which is a setting that shares features with LTC but also has some notable differences. Shared characteristics between critical care and LTC include complexity of medical needs, frequent reliance on surrogate decision-makers, and prognostic uncertainty of patients. Major differences include different regulatory requirements, fewer physician visits in LTC, and possible engagement of staff as “family” among LTC residents. Although there is a paucity of research on the specifics of family meetings in LTC, strategies for effective family meetings can be garnered from research and expert opinion from family meetings that have occurred in critical care and palliative care settings. Strategies that have been outlined to promote effective family meetings in these settings can be grouped into three categories: (1) timing of family meetings; (2) use of a step-by-step process; and (3) communication techniques to support families and facilitate shared decision making. Each of these strategies should apply equally well to the LTC setting for families of residents who are facing critical junctures.

Timing of the Family Meeting

Researchers in critical care have demonstrated the value of proactive family conferences, with family meetings occurring at regular intervals, rather than only at times of crisis.11-15 In the LTC setting, family meetings should occur around the time of admission; be considered at a regular interval, as appropriate to change in resident status; and when there is any major change in health status, such as declining function or weight, repeated infections, or a new life-limiting diagnosis.16 Creating specific triggers for family meetings for LTC residents and incorporating effective communication approaches can improve communication and reduce anxiety for residents, families, and staff because care goals become clear and are better matched to a resident’s goals and values.

Step-by-Step Process

Conducting a family meeting should be thought of as a skill, and it is best managed by using a stepwise approach that provides a clear path for sharing information, managing emotions, and establishing goals (Table 1).17 The use of a process for conducting family meetings is described in multiple research studies and consensus-based guidelines.5-10,14-19 Although the recommended number and description of process steps for family meetings vary, they are all similar and include a preparation phase, a meeting phase, and a post-meeting phase.20-22 As with any procedure, the preparation phase is crucial to a successful outcome. During this phase, clinicians should first have a thorough understanding of the patient’s medical condition(s), prognosis (both functional and time), and current treatment plan.

Second, clinicians must know if the resident is decisional, meaning that he or she is capable of making his or her own medical decisions, and if not, who is the legally designated decision-maker. If the patient is not decisional, clinicians must be aware of any advance care planning documents and their content.

Third, there is a need to decide who should be present from among the LTC staff and who will serve as the meeting leader. An individual from any clinical background can serve as the leader, assuming that he or she has mastered the key steps and communication skills of leading a family meeting.14,23 Last, all relevant family members should be given information about the meeting, including the purpose, time, and place, and should be invited to bring whichever family members wish to attend. Distribution of printed informational materials, such as a pamphlet describing the purpose of a family meeting, and advising families to use a pre-meeting questionnaire is encouraged.4,24,25

For meetings during periods of health instability, it is crucial that staff have reviewed and discussed treatment options with the involved clinicians, including the option of withdrawing or withholding a life-sustaining treatment. Several authors have outlined the importance of clarifying communication among the healthcare team before the family meeting so that major disagreements between consulting clinicians are resolved, as receiving conflicting information is a major source of distress and dissatisfaction for families.14,22,26 The initial steps in leading the actual meeting include ensuring a comfortable, quiet meeting environment and allowing all participants to introduce themselves. Clinicians can build a positive and trusting relationship by inviting family participants to state their understanding of the resident’s medical problems, prognosis, and treatments, before the staff reviews his or her current health status.6 Following the discussion of the medical facts, it is essential to provide an opportunity to elicit questions and respond to resident or family emotions.

At times of health instability in the LTC setting, where it is common for some residents to die from one or more chronic diseases, emotional reactions from both residents and family are normal, including grief, sadness, anger, and even relief. A vital aspect of meeting leadership is to recognize these emotions and provide time for discussion, as key decisions concerning future medical care interventions cannot be made until the emotions are first explored. If the status of the resident is such that the choice of treatment approaches includes either interventions to attempt life prolongation (eg, antibiotics for pneumonia in the setting of dementia) versus withdrawing or withholding further life-sustaining treatments (eg, no antibiotics), families typically fall into two groups: those who accept the impending death of their loved one and those who do not.

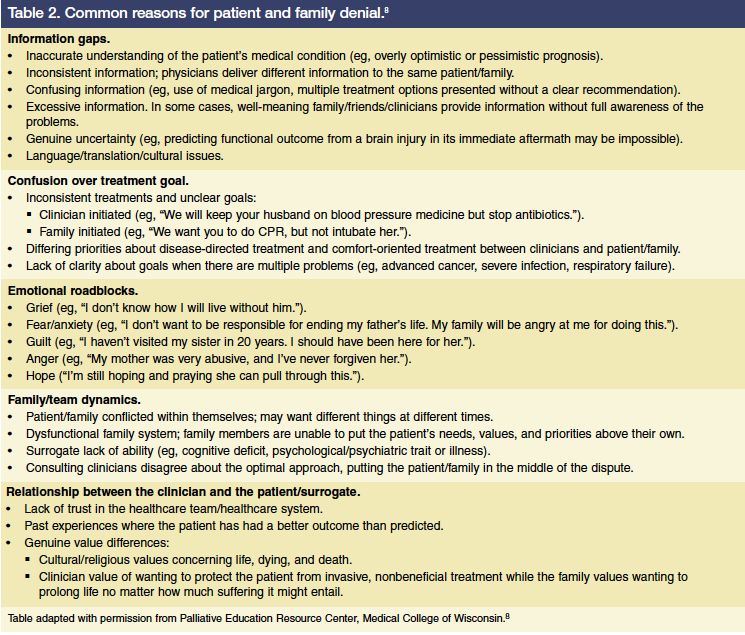

Families who accept that death is coming and are ready to prepare for that eventuality may ask questions such as “How long?,” “What do we do?,” and “Will there be suffering?” Families who are not ready to accept that death is imminent may say things like “We want another opinion,” “You must be wrong,” or “We believe in miracles.” Denial is usually a very helpful adaptive coping mechanism for chronically ill residents and their families, but can occasionally become maladaptive, complicating the decision-making process. Families who are not ready to accept death are often described by clinicians as being in denial; however, saying that someone is in denial often closes a window into a deeper understanding of the underlying issues, as a range of potential reasons underlay the appearance of denial (Table 2).8 Expertise in leading family meetings is exemplified by clinicians who can determine which of the many factors is limiting acceptance of the resident’s impending death and develop an intervention plan that addresses the noted cause(s). When the resident and family are emotionally ready, specific goals can be elucidated and plans to meet these goals can be developed.16,23

For residents who have stable medical problems, issues for discussion in the LTC setting include advance care planning (eg, designation of a surrogate decision-maker; wishes regarding the use of future life-prolonging treatments, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation), prioritizing goals related to comfort, and developing methods to maintain function.27,28 For residents with deteriorating medical problems, issues for discussion include use of specific life-prolonging treatments (eg, feeding tube for weight loss), future hospitalizations, location of future care, and need for additional resources such as hospice care.

The post-meeting phase includes two components: documentation and debriefing. Use of a specific family meeting documentation tool is encouraged to improve communication between care providers.4,29,30 Important content to be documented includes who was present, what was discussed, what was decided, and the next steps. In the LTC setting, it is crucial to document decisions regarding future hospitalization; specific medical treatment wishes, such as those documented within the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST) paradigm (www.ohsu.edu/polst); use of time-limited treatment trials; and other issues that need follow-up to help LTC staff understand resident and family wishes and values concerning future medical care decisions.27

To ensure proper care of LTC patients with complex medical issues, it is critical that these documents are made available to other medical settings. Giving families a copy of what was discussed during the family meeting is also a practice that has been associated with a positive family reaction.14 Debriefing is encouraged following all family meetings, as these meetings may result in many emotions arising for the staff. Debriefing provides an opportunity to share personal feelings, obtain support from other staff members, and discuss opportunities to improve the care planning process.10,22 This may be an especially important step in the LTC setting because of the close, personal relationships that often develop between staff and residents.

Specific Communication Techniques

The third category of strategies addresses specific communication techniques and behaviors. Feedback from families and residents about clinician communication during family meetings sheds light on what families view as effective communication techniques. In assessments of families of patients in intensive care units (ICUs), assurances of nonabandonment, patient comfort, and support for family decisions have been identified as being helpful, and such assurances are likely to provide comfort to families in LTC settings as well.3,31,32 Research on missed opportunities during family meetings in ICUs supports the importance of listening and responding to family emotions, and eliciting the support of surrogate decision-makers in a process of shared decision making.14,33,34 A report on communicating with family caregivers of LTC residents found that face-to-face meetings with physicians were associated with favorable perceptions of communication at the end of life.35

A central task for family meeting leaders is to identify and respond effectively to verbal and nonverbal communication cues. Experienced clinicians recognize that anger, a common emotion among family members confronted by bad news or impending death of their loved one, is most likely a sign of fear.36 In such cases, an effective strategy is to become empathic, rather than defensive. Empathy can be demonstrated with statements such as “This must be hard for you” or “I can’t imagine what you are going through.” Similarly, excellent communicators know that when a family member says, “Do everything” or “We believe in miracles,” that the underlying emotions driving these statements are typically guilt (eg, “I haven’t visited enough”), anger (eg, “She was an alcoholic and lousy parent”), or fear (eg, “The healthcare team is abandoning us”).18,37 Careful exploration of the reasons and values behind these requests are needed to help family members make decisions that are truly in the best interest of their loved one. Using supportive statements such as “I wish things were different,” discussing what can be done for the resident before discussing what will not be done, and supporting positive coping behaviors facilitate communication and decision making.5-10

Conclusion

Family meetings are an evidenced-based practice to clarify goals of care and support communication between families and the healthcare team. Evidence from the critical care and palliative care literature supports three components for effective family meetings: (1) meetings are best held proactively; (2) meetings are based on adherence to a step-by-step process; and (3) meetings must incorporate communication techniques that support family decision making. Implementation of family meetings in the LTC setting is an effective strategy to improve both family satisfaction and the quality of care for residents facing complex medical decisions due to unstable conditions. Further research and testing in LTC settings of approaches found to be effective in ICUs and palliative care settings is warranted.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Ceronsky is director, Palliative Care, University of Minnesota Medical Center, Fairview, Minneapolis, MN, and Dr. Weissman is professor emeritus, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI.

References

1. Meier DE, Morrison RS, Cassel CK. Improving palliative care. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(3):225-230.

2. National Quality Forum. A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality: A Consensus Report. 2006. Accessed October 19, 2010.

3. Curtis J, Engelberg R, Wenrich M, et al. Studying communication about end-of-life care during the ICU family conference: development of a framework. J Crit Care. 2002;17(3):147-160.

4. Nelson JE, Walker AS, Luhrs CA, et al. Family meetings made simpler: a toolkit for the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2009;24(4):626.e7-626.e14.

5. Weissman DE, Quill TE, Arnold RM; Palliative Education Resource Center, Medical College of Wisconsin. Preparing for the Family Meeting. Fast Facts and Concepts #222. December 2009. Accessed October 19, 2010.

6. Weissman DE, Quill TE, Arnold RM; Palliative Education Resource Center, Medical College of Wisconsin. The Family Meeting: Starting the Conversation. Fast Facts and Concepts #223. December 2009. Accessed October 19, 2010.

7. Weissman DE, Quill TE, Arnold RM; Palliative Education Resource Center, Medical College of Wisconsin. Responding to Emotions in Family Meetings. Fast Facts and Concepts #224. January 2010. Accessed October 19, 2010.

8. Weissman DE, Quill TE, Arnold RM; Palliative Education Resource Center, Medical College of Wisconsin. The Family Meeting: Causes of Conflict. Fast Facts and Concepts #225. January 2010. Accessed October 19, 2010.

9. Weissman DE, Quill TE, Arnold RM; Palliative Education Resource Center, Medical College of Wisconsin. Helping Surrogates Make Decisions. Fast Facts and Concepts #226. February 2010. Accessed October 19, 2010.

10. Weissman DE, Quill TE, Arnold RM; Palliative Education Resource Center, Medical College of Wisconsin. The Family Meeting: End of Life Goal Setting and Future Planning. Fast Facts and Concepts #227. February 2010. Accessed October 19, 2010.

11. Campbell ML, Guzman JA. Impact of a proactive approach to improve end-of-life care in a medical ICU. Chest. 2003;23(1):266-271.

12. Campbell ML, Guzman JA. A proactive approach to improve end-of-life care in a medical intensive care unit for patients with terminal dementia. Crit Care Med 2004;32(9):1839-1843.

13. Machare Delgado E, Callahan A, Paganelli G, et al. Multidisciplinary family meetings in the ICU facilitate end-of-life decision making. Am J Hospice Pall Med. 2009;26(4):295-302.

14. Hudson P, Quinn K, O’Hanlon B, Aranda S. Family meetings in palliative care: multidisciplinary clinical practice guidelines. BMC Palliat Care. 2008;7:12.

15. Lilly CM, De Meo DL, Sonna LA, et al. An intensive communication intervention for the critically ill. Am J Med. 2000;109(6):469-475.

16. Weissman DE. Decision making at a time of crisis near the end of life. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1738-1743.

17. Conducting a Family Goal Setting Conference Pocket Card; End-of-Life/Palliative Education Resource Center, Medical College of Wisconsin; 2010.

18. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Health Care Guideline: Palliative Care. 3rd ed. November 2009. Accessed October 19, 2010.

19. Back A, Arnold R, Tulsky J. Mastering Communication with Seriously Ill Patients. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

20. von Guten CF, Ferris FD, Emmanuel LL. The patient-physician relationship. Ensuring competency in end-of-life care: communication and relational skills. JAMA. 2000;284(23):3051-3057.

21. Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Shannon SE, et al. The family conference as a focus to improve communication about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: opportunities for improvement. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(2 Suppl):N26-N33.

22. Griffith JC, Brosnan M, Lacey K, et al. Family meetings: a qualitative exploration of improving care planning with older people and their families. Age Aging. 2004;33(6):577-581.

23. Bluestein D, Latham Bach P. Working with families in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8(4):265-270.

24. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. Impact of a family information leaflet on effectiveness of information provided to family members of intensive care unit patients: a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(4):438-442.

25. Moneymaker K. The family conference. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(1):157.

26. Curtis JR, White DB. Practical guidance for evidence-based ICU family conferences. Chest. 2008;134(4): 835-843.

27. Corcoran AM. Advance care planning at transitions in care: challenges, opportunities, and benefits. Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging. 2010;18(4):26-29.

28. Gillick MR. Adapting advance medical planning for the nursing home. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(2):357-361.

29. Center to Advance Palliative Care: Clinical Tools. Accessed July 31, 2010.

30. Tracy MF, Ceronsky C. Creating a collaborative environment to care for complex patients and families. AACN Clin Issues. 2001;12(3):383-400.

31. Abbott KH, Sago JC, Breen CM, et al. Families looking back: one year after discussion of withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining support. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(1):197-201.

32. Stapleton RD, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MM, et al. Clinician statements and family satisfaction with family conferences in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(6):1679-1685.

33. Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(8):844-849.

34. McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1484-1488.

35. Biola H, Sloane PD, Williams CS, et al. Physician communication with family caregivers of long-term care residents at the end of life. J Am Geriatr So. 2007;55(6):846-856.

36. Wang-Cheng R. Dealing with the Angry Dying Patient. 2nd ed. Fast Facts and Concepts #59. July 2006. Accessed October 19, 2010.

37. Quill TE, Arnold R, Back AL. Discussing treatment preferences with patients who want “everything.” Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(5):345-349.