Happy in Her Son’s World

Affiliations: Department of Family Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA

Abstract: Providing efficient long-term care services for the aging US population is one of the most difficult public policy challenges of the 21st century. High cost and consumer preference have been shifting long-term care away from institutional settings and toward home- and community-based care; this pattern is expected to continue. Rehabilitation for older persons has acquired an increasingly higher profile among policy makers and service providers within health and social care agencies, generating growing interest in the use of alternative care environments, including home care settings. This case illustrates how effective navigation of the healthcare system and utilization of resources enabled an older adult with multiple medical conditions to transfer from a nursing home to a home care setting, resulting in fewer hospitalizations and an enhanced quality of life.

Key words: Home care, community-based services, quality of life, care planning, activities of daily living.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The provision of long-term care services has become one of the most difficult public policy challenges within the context of an increasingly aging US population.1 Worldwide, the proportion of older adults is projected to grow from 6.9%, as recorded in 2000, to 19.3% by 2050.2 Nursing home care is a subset of long-term care, but one that receives a great deal of policy attention because of the expenditure of public funds via Medicaid after “spend-down.”3 Traditionally, nursing home care has been reserved for patients who require skilled nursing care as well as comprehensive rehabilitative services. The lack of or limited affordable alternatives to nursing home care are important contributors to the number of patients who remain in nursing homes despite the likelihood that a home- or community-based setting might fulfill the same level of care. Over the past two decades, in response to the high cost of nursing home care to state Medicaid programs, which pay for approximately 50% of all nursing home care, and the desires of patients and families for alternatives to institutionalized care, states have begun to explore initiatives and programs that enable transitions out of nursing homes.4 As a direct result, the Medicaid waiver programs evolved, which waive certain eligibility requirements and enable those who do not qualify for full Medicaid to take advantage of various home care benefits, with the requirement that the patient incur some of the cost for services.5 Assistance with activities of daily living (eg, bathing, dressing, meal preparation and eating assistance, household chores) for often up to 8 hours per day is an important component that may allow many nursing home residents to successfully transition to the community setting and successfully age in place. In addition, waiver programs may provide home health services, such as in-home visits by nurses, aides, and physical or speech therapists, as well as emergency response systems and caregiver support.5 Similarly, for older adults currently living in the community, modalities such as geriatric home visitation may decrease the disability burden and provide better quality of care with less frequent utilization of acute care services.6,7 Such programs aim to maintain the health and autonomy of elderly adults through integrated home-care management by an interdisciplinary team of primary care physicians, nurses, social workers, and other care providers.

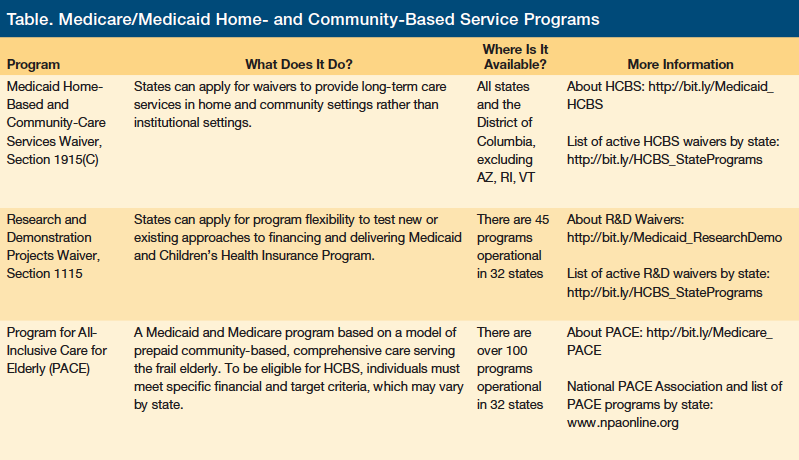

In this article, we present a case that illustrates the effective use of one of these waiver programs—the Home- and Community Based Services (HCBS) Medicaid Waiver program. Combined with geriatric home visitation, the program allowed an older adult with multiple medical conditions, including vascular dementia, to successfully transition from the nursing home to her son’s home and to remain there long-term. A brief discussion of these and other state programs is also provided.

Case Report

An 84-year-old woman with a medical history significant for moderate vascular dementia, hypertension, type 2 insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia received monthly to bimonthly geriatric home visits and periodic medical care from our primary care clinic. The patient had been living alone in her own home in South Carolina until 2007. She experienced multiple falls and had suboptimal control of her hypertension and diabetes, which resulted in numerous emergency room visits. In addition, the patient was often discovered wandering around in a confused state by her neighbors. It became apparent that she was having difficulty adequately caring for herself. The patient’s son decided to relocate her to Georgia, where he resided. En route, she was admitted in the hospital, where a computed tomography of the head showed multiple chronic subdural hemorrhages and severe dehydration. Upon hospital discharge, the patient was transferred to a nursing home for continuation of supportive care, and she was regularly visited by her son, who was also an active participant in discussions involving her plan of care. After 8 months of nursing home stay, her son decided to take her home with him. Although traditional home care covered by Medicare was made available at the time of discharge, this patient required long-term assistance with activities of daily living that Medicare only provides in conjunction with other skilled nursing or therapeutic care. Therefore, we assisted the patient in obtaining care under the state of Georgia’s Medicaid HCBS Waiver program, which provided a home health aide for 5 days per week for 8 hours per day to assist with the patient’s activities of daily living. Our assistance with parsing the Family and Medical Leave Act, guardianship, and the provision of pharmaceutical samples further facilitated the transition. We continue to perform bimonthly geriatric home visits and have been successful in decreasing this patient’s acute care utilization to one hospitalization in 6 years. Her hypertension and diabetes are now well controlled.

Discussion

Older Americans now comprise the fastest growing segment of the nation’s population; this age group has increased by approximately 10 million since 1980, with the largest increase among those aged 85 and older.8 By the year 2030, one in five Americans will be older than age 65.8 This expanding population has resulted in an ever-increasing need for long-term care services; however, many individuals seeking to transition from institutional care merely need assistance with activities of daily living and not skilled nursing care. The problem is that the provisions for home care under Medicare often fail to meet the actual needs of older adults and others experiencing functional decline. Medicare provides coverage for a home health aide only if skilled home nursing care is already in place. As such, the availability of state HCBS waiver programs with the provision for assistance with activities of daily living on a long-term basis may allow many older adults to transition successfully from nursing homes to community settings. Waivers target individuals who meet the criteria for institutional care (ie, the aged, aged or disabled, individuals with physical disabilities or intellectual and developmental disabilities, medically fragile or technology-dependent children, individuals with HIV/AIDS, and those with traumatic brain and/or spinal cord injury). Most participants, depending on their state’s financial criteria, will have to pay a portion of their income toward the cost of their care. In 2009, 1,366,337 individuals received HCBS via Medicaid waiver programs.9

Although early studies on the benefits of HCBS waiver programs have not yielded significant outcomes, recipients have reported high satisfaction with the quality of care and lower hospital utilization.10 More recent studies have examined the efficacy of these services. For example, an Indiana study concluded that the volume of Medicaid HCBS waivers that targeted activities of daily living (eg, attendant care, household chores, home-delivered meals) was associated with a decreased risk of nursing home placement for each 5-hour increment in personal care and household services received.11

The other relevant type of waiver is section 1115 Research and Demonstration projects, which enable states to have the flexibility to test new or existing approaches to financing and delivering Medicaid. One example is the ongoing Independence at Home health program, a provision of the Affordable Care Act, which was initiated to test the effectiveness of expanding house-call medicine. In order to demonstrate benefit, the program will provide a payment incentive to healthcare providers who can show improvement in outcomes, such as a reduction in hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and readmissions, through the provision of timely in-home primary care visits to Medicare beneficiaries with multiple chronic illnesses and functional impairment. In 2012, 15 medical practices across the United States agreed to participate in a demonstration period of 3 years, and includes 10,000 home-limited Medicare beneficiaries.12-14 Participating home-based care practices were included if they were led by physicians or nurse practitioners, had experience providing home-based primary care to patients with multiple chronic conditions, and served at least 200 eligible beneficiaries.14 If they meet the savings target of 5%, participating practices will be eligible for varying levels of savings shares to help finance the incremental costs of the program.13 The results from this demonstration are intended to help to inform further utilization and/or improvements to existing home- and community-based long-term care alternatives.

Another option is the Program for All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), a Medicaid and Medicare program based on a model of prepaid community-based, comprehensive care serving the frail elderly. PACE is available in 32 states.15,16 To be eligible for HCBS, individuals must meet specific financial and target criteria17: aged 55 years or older, reside in service area of a PACE organization, be able to live safely in the community with help from PACE, and need nursing home-level care, the criteria for which varies from state to state. Once eligible, individuals may be placed on a waiting list when programs are at capacity or due to inadequate funding. Assistance provided through PACE can include adult day care, primary care (including doctor and nursing services), laboratory/X-ray services, meals, dentistry, social services, nutritional counseling, drug prescriptions, transportation, occupational and physical therapy, and other services.

A review of these programs is provided in the Table. To examine the comparative effectiveness of community-based care alternatives, a South Carolina study compared 5-year survival rates among entrants (N=2040) to a Medicaid waiver program, nursing homes, and PACE.15 After accounting for risk, results demonstrated that the mortality risk was lower in waiver participants (58.8%) than in PACE (72.6%) and nursing home participants (71.6%).15 However, the median survival for waiver enrollees was 3.5 years, with PACE and nursing home participants surviving 4.2 and 2.3 years, respectively. Accounting for risk, the advantage of PACE was significant (P=.015). Of note, PACE participants were generally older frail adults with multiple risk factors, including deficits in both cognition and activities of daily living, and therefore most likely to benefit from comprehensive care.15

Additional modalities, such as geriatric home visitation, can play an important role in enabling older adults to remain in their own homes (ie, “age in place”) and may lead to reduced acute care utilization. For example, a systematic review by Stuck and colleagues18 found that preventive home visitation programs have been deemed effective, provided the modality is a multidimensional geriatric assessment with follow-up, and they have been shown to have greater mortality benefit for elderly patients younger than 80 years of age.

Conclusion

Physicians and other healthcare providers stand at the forefront of advocacy for patients, ensuring that they have the best resources available to preserve health and improve outcomes. There is a need for providers to be familiar with the different community-based alternatives to long-term institutional care offered by our individual states as a means to enhance quality of life and lower healthcare costs. In addition, it is crucial that we continue to visit our patients in their homes to provide guidance and recommendations for ways of improving quality of care while prolonging or avoiding the need for institutional care.

References

1. Feder J, Komisar HL, Niefeld M. Long-term care in the United States: an overview. Health Affairs. 2000;19(3):40-56.

2. Gavrilov LA, Heuveline P. Aging of population. In: Demeny GP, McNicoll G, eds. The Encyclopedia of Population Vol. 1. New York: McMillan: 2003:32-33.

3. Taylor DH Jr, Sloan FA, Norton EC. Formation of trusts and spend down to Medicaid. J Gerontol B Pyschol Sci Soc Sci. 1999:54(4):S194-S201.

4. Kasper J. Who stays and who goes home: using national data on nursing home discharges and long-stay residents to draw implications for nursing home transition programs. https://kff.org/medicaid/report/who-stays-and-who-goes-home-using. Published August 30, 2005. Accessed January 28, 2015.

5. Home and community services: a guide to Medicaid waiver programs in Georgia. Georgia Department of Community Health website. https://dch.georgia.gov/

medicaid-publications. Accessed January 28, 2015.

6. Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2623-2633.

7. Huss A, Stuck AE, Rubinstein LZ, Egger M, Clough-Goor KM. Multidimensional preventive home visit programs for community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(3):298-307.

8. Kinsella K, Phillips DR. Global aging: the challenge of success. Population Bulletin. 2005;60(1):1-44.

9. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Medicaid and Community-Based Services Programs 2009 Data Update. 2012(Dec):8-9.

10. Mitchell G 2nd, Salmon JR, Polivka L, Soberon-Ferrer H. The relative benefits and cost of Medicaid home- and community-based services in Florida. Gerontologist. 2006;46(4):483-494.

11. Sands LP, Xu H, Thomas J 3rd, et al. Volume of home- and community-based services and time to nursing-home placement. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2012;2(3).

12. Independence at home demonstration. CMS website. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/independence-at-home. Accessed March 24, 2015.

13. Independence at home frequently asked questions for applicants. www.cms.gov. Published December 2011. Accessed March 24, 2015.

14. What is the Independence at Home Act? IAH website. Accessed March 24, 2015.

15. Wieland D, Boland R, Baskins J, Kinosian B. Five-year survival in a program of all-inclusive care for the elderly compared with alternative institutional and home- and community-based care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(7):721-726.

16. PACE in the states. National PACE Association website. www.npaonline.org. Accessed March 24, 2015.

17. Smith G, O’Keeffe J, Carpenter L, et al. Understanding Medicaid home and community services: a primer. https://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/primer.pdf. Published October 2000. Accessed January 28, 2015.

18. Stuck AE, Egger M, Hammer A, Minder CE, Beck JC. Home visits to prevent nursing home admission and functional decline in elderly people: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. JAMA. 2002;287(8):1022-1028.

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to:

Folashade S. Omole, MD, FAAFP

Morehouse School of Medicine

Department of Family Medicine

1513 Cleveland Avenue, Building 500

East Point, GA 30344

fomole@msm.edu