Geriatrics Care Team Perceptions of Pharmacists Caring for Older Adults Across Health Care Settings

Medication-related problems during transitions of care impose a burden on the health care system, adversely affecting patient care. To address this, at the authors’ practice, geriatrics-trained pharmacists are incorporated into a geriatric care team. The pharmacists provide direct, real-time care across health settings, including outpatient and inpatient settings and nursing facilities. To gain feedback on the pharmacists’ impact in this practice, focus groups made up of the involved physicians, nurses, and staff were created. Three themes emerged based on participant feedback: (1) comprehensive medication management is a key element to pharmacists improving patient quality of care; (2) medication expertise is a critical factor contributing to the trust health care team members have for pharmacists; and (3) improved workflow for providers and staff is a result of pharmacist integration into care. One theme also emerged regarding suggestions on how to increase pharmacist presence and involvement, in addition to other non-themed suggestions. Perceived quality of care for the health care team and patient and families was increased with the pharmacist. Future research will evaluate cost effectiveness and the effect on patient outcomes.

Key words: focus groups, geriatric, pharmacist, older adults, transitions

Transitions of care represent a challenge for older adults with complex medication regimens and multiple morbidities. Medication-related problems during transitions from one care setting to another and subsequent increases in morbidity, mortality, and health care utilization are increasingly recognized as major public health problems among older adults.1-5 Practice development, research, and recent policy changes have focused on improving care during these transitions. Unfortunately, direct pharmacist involvement in geriatric medication use across care settings is often limited.1-8

Since 2005, our geriatric care team has taken a unique approach to coordinated care by incorporating a pharmacist as a key member of the patient care team—what we refer to as the Pharmacist-led Intervention on Transitions of Seniors (PIVOTS) strategy. PIVOTS is a grant-funded research project that evaluates how pharmacists work with physicians and other members of the health care team in real time to make medication therapy decisions and communicate drug-therapy problems. In our practice, physicians, nurse practitioners, psychiatrists, social workers, and pharmacists collaboratively care for geriatric patients across health care settings, including two outpatient physician practices, an academic community teaching hospital, a skilled nursing facility (SNF), and a personal care facility. As part of this care team, the pharmacists manage medications in real time for older adult patients as they transition between settings (eg, home to hospital, hospital to SNF, etc). Details regarding this approach has been described in PIVOTS group publications.9

Our PIVOTS team vision is to evaluate the pharmacists’ patient-focused approach for older adults, which supports continuity of care before, during, and after care setting transitions. Through partnership with a local school of pharmacy, our PIVOTS team set the goal to identify, measure, and evaluate key outcomes of this novel practice to improve how care is provided for patients and to ensure that it was replicable, scalable, and sustainable. This current work by a subset of PIVOTS team researchers describes one aspect of that—health care team perceptions.

The goal of this study was to describe our health care team’s perceptions of the impact of the pharmacist on the team workload, workflow, care quality, practice, and communication. These findings will provide key information to facilitate development of a transferable and sustainable practice for pharmacists providing care to older adults across the care continuum.

Focus Group Participants and Study Design

This research was approved by the University of Pittsburgh/University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Three focus groups were created to elicit perceptions of the pharmacists’ impact on the geriatric care team in caring for patients as a part of the team. Each focus group was composed of individuals with similar patient care roles to allow participants to more comfortably share their insights and avoid hierarchal intimidation.10 The three groups were: (1) physicians who were geriatric team members that practiced in the outpatient physician offices, SNFs, and/or associated community teaching hospital; (2) nurses and nonprofessional staff who were geriatric team members practicing at the outpatient physician offices; (3) nurses and nonprofessional staff working at the SNFs and/or personal care facilities. Focus group participants were recruited via paper flyers, emails, and verbal communications based on employment location and professional degree. The goal was to include between 6 and 10 participants in each focus group. One participant in the focus groups was also a member of the PIVOTS research team.

The goal of the focus group sessions was to elicit attitudes, feelings, and perceptions of the pharmacists’ actions and contributions to patient care based around the following five domains: workload, workflow, care quality, practice, and communication. A facilitator interview guide was developed addressing these domains. Probing questions within each domain were generated based on gaps within existing literature, practice site clinical expertise, and goals of the study.

Focus groups were led by a trained facilitator and co-investigator (K.C.) using the interview guide. The primary investigator (A.H.) served as the co-facilitator and was present for each session. One student pharmacist was present for each focus group to record observational field notes. Each focus group session was allotted 90 minutes and audio-recorded. De-identified participant demographic information was collected through a questionnaire and submitted at the completion of the focus group. Focus groups were conducted over a 1-month period between January and February 2014, in a private conference room within the community teaching hospital.

Focus group audio files were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using a combination of inductive and deductive approaches to code the data.11 Preliminary codes were developed by the primary investigator, with consideration to the five domains described previously. A code book was established and further refined as new concepts emerged from the coding process. The transcripts were coded independently by two investigators (A.H. and L.S.) using ATLAS.ti version 7 (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH). Coders then discussed and resolved any coding discrepancies and identified preliminary themes.

An expert panel was formed from the PIVOTS research team based on prior experience with qualitative analysis and clinical expertise. Each expert panel member independently read the transcripts and then met to validate the coders’ preliminary themes and elicit additional subthemes. Consensus was reached on the final themes, and specific quotations were selected that best represented each theme. Final review of the data and results was conducted by all members of the PIVOTS group.

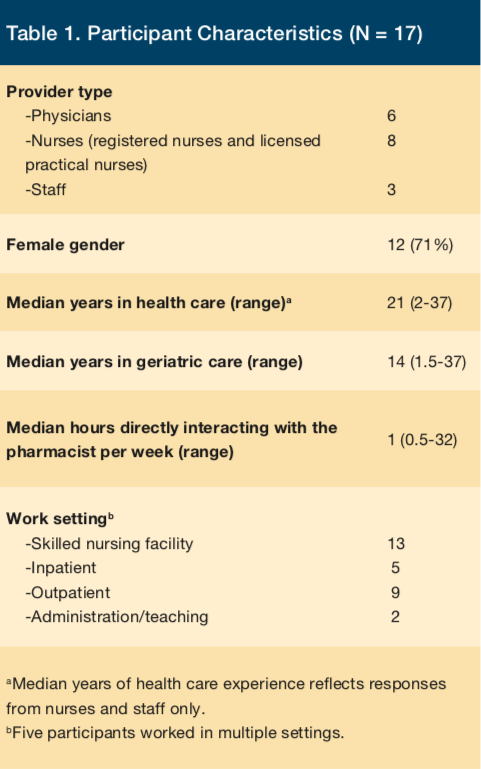

A total of 17 professionals participated in the focus groups (Table 1). Participants included 6 physicians, 8 nurses, and 3 staff members. Most participants had worked in health care for a significant period of time (median 21 years) and in geriatric care in particular (median 14 years).

Pharmacists’ Impact on the Care Team

The qualitative analysis elicited the following three themes related to how pharmacists impacted the geriatric care team. At each theme, selected quotations from focus groups are provided that were determined to best represent each theme.

Theme I. Comprehensive medication management is a key element to pharmacists improving patient quality of care

Participants reported that pharmacists improved the quality of their patients’ health care by facilitating accurate accounting of medication use, increasing coordination of care and contributing to continuity between care settings. Pharmacists’ medication-related expertise improved quality specifically through comprehensive medication management, patient medication education, and identification of medical history relevant to medications.

“I think they [patients] get a lot more clarity on their medications, what [indication] they’re for…interactions [with medications over the counter]…how to take them more easily…dosage [form]…pill boxes…automatic dispensers…multiple medications.”

—Physician

“But it’s nice with [the pharmacist] because she gets back to us so quickly, and we get [the warfarin order] in right away…that [warfarin] is going to be there [from the dispensing pharmacy] that evening…so that definitely improves patient care.”

—Nursing facility staff

“If [the patient and families have] been to another primary care doctor and they get their 15 minutes with their doctor, and they come to our office, they get a half an hour with the pharmacist, and then they get a half an hour with the physician, and the families and the patients come out [saying], ‘I can’t believe I didn’t do this sooner. I can’t believe my mom hasn’t been in this setting sooner. Things are so much better in this setting.’”

—Outpatient nurse/staff

“…since [the pharmacists] do rounds on our patients in the hospital, and we get a lot of those patients in the office or pick-up…[the pharmacist] knows the patients and the history, so [the pharmacist] can follow from what…may have happened in the hospital right into the office…”

—Outpatient nurse/staff

Theme II. Medication expertise is a critical factor contributing to the trust health care team members have for pharmacists

Trust was a common theme in all focus group sessions, and participants regarded the pharmacist as the medication point person. This trust was often related to the pharmacists’ expertise in medication reconciliation, education, and medication management of high-risk medications (eg, anticoagulants, antipsychotics). Participants also perceived that patients and caregivers depend on the pharmacist once a relationship is established between patient and pharmacist. They explained that recipients of the pharmacist’s services feel confident in the care they receive from the pharmacist.

“To me, I’d be lost without the pharmacist...they are just a wealth of information, particularly to the doctors. The doctors just are so grateful and appreciative because the pharmacist has that insight… [of] the mechanism, how the meds work, [that patients are] not taking their medications, [or taking them] at the wrong time…then they do that teaching [to patients and families].”

—Outpatient nurse/staff

“[When the pharmacists are not in the office], we’d have to review the meds. We have to answer questions that…I don’t feel as [comfortable answering]…I don’t have that knowledge base…the patients do look forward to [meeting with the pharmacists]…and feel more confident because, on top of having a regular doc, they have a doctor who knows all about their medicines.”

—Outpatient nurse/staff

“The families [of older adults] feel more educated [with the pharmacist]. They all come with the daughter or five daughters. And you know, with the pharmacist being able to explain to all five daughters, all five daughters are now on the same page.”

—Outpatient nurse/staff

“[The pharmacists] just work side-by-side…with the doctors…one [patient] today, after she was done meeting with [the pharmacist for] med management…she just commented to [the pharmacist], ‘Well, young lady, you have been extremely thorough today. I greatly appreciate all your help because I learned something, and who knew I could learn something at 85?’”

—Outpatient nurse/staff

Theme III. Improved workflow for providers and staff is a result of pharmacist integration into care

Participants explained that their workflow was positively affected when the pharmacists were involved with patient care. Pharmacists provided timely, individualized care to older adult patients, enabling nurses, staff, and physicians more freedom to attend to their other responsibilities.

“[The pharmacists take a more detailed] history of the patient’s medication. And also…spend more time teaching [the] patient how properly to use medication. [The pharmacists] also advise me about interaction with certain drugs, which I probably wouldn’t have [enough time to look up on my own.]”

—Physician

“[The pharmacists] also [retrieve patient self-monitoring values] better than we [physicians] do. It can be weeks before I get somebody’s blood sugar [readings] in the office….[The pharmacists do this] a lot more efficiently…it’s more on their radar screen than it is mine….you say, ‘Oh, yeah, well [a patient] forgot to send me her blood sugars this week.’….I’ll get an email [from the pharmacist stating], ‘This is [the patient’s blood sugar] numbers for the week. I think this is what we should do to modify their insulin.’”

—Physician

“[The pharmacist] helps my patient flow because I get off the phone, or I don’t have to go to the phone in many instances [because the pharmacist takes or returns the phone call for me], where I previously had to.”

—Physician

“I would say [the pharmacists’ impact on my workflow is a] positive improvement. [The pharmacist in the outpatient office sees] the patient before me [to] give me...[an] idea and helps me to manage medication[s]…especially [the] complexity of the medications. And also, [the pharmacist] documents what [he/she does so that] later on I [refer to the information and that helps] me to spend less time but be efficient and effective.”

—Physician

Suggestions for Enhancing Pharmacists’ Practices

Throughout each focus group, participants also discussed ways to make the pharmacists’ duties better for both themselves and the patients. Upon analysis, a single theme emerged on how to optimize pharmacists’ presence on the care team.

Theme IV. Consistency of the pharmacists’ schedules and responsibilities would optimize their impact

Focus group participants expressed the desire to make pharmacist duties more consistent. This was described in two main ways: (1) having the pharmacist available at all care settings when patients are being seen, and (2) having the pharmacist providing, communicating, and documenting services similarly to other providers and staff. In addition to participants’ preference for the pharmacists’ presence in all of the care settings, they also said the pharmacists’ activities should be scheduled to coincide with physicians and staff.

“I would like to see [the pharmacists] more…because there are…several doctors who don’t have [the pharmacist] available when their patients go [to the physicians’ office].”

—Outpatient nurse/staff

“In the nursing home, I have…help [from the pharmacist]. They often do a medicine review….But it usually comes a couple days after I’ve seen the patient. So for me, it would be helpful to have one-on-one time with the pharmacist [while in the nursing home]….And it would be nice when I’m seeing the patient…to have the pharmacist there to go over it...bounce ideas off of [in real time].”

—Physician

The participants also indicated that having the pharmacists’ routinely providing care and communicating and documenting their activities in the medical record would optimize their impact. This would allow the pharmacist to play a larger role on the geriatric team, thus decreasing the workload of physicians and other staff. This potential for greater impact was especially noted in the SNF setting, as illustrated with the following quotes:

“From a documentation standpoint, I would like it if the pharmacist could have more of an active role in the actual charting that is required [for billing and regulatory requirements] for patients…[to] decrease my workload [through their notes]….It would be nice if they saw deficits [in therapies, and] they could make changes [independently].”

—Physician

“I get emails from the pharmacists regarding the nursing home patients, and sometimes there’s information in there that…should be taken care of fairly quickly. And email is not always the fastest way to reach me. So if there’s something critical, it could be done through a phone call or paging or something.”

—Physician

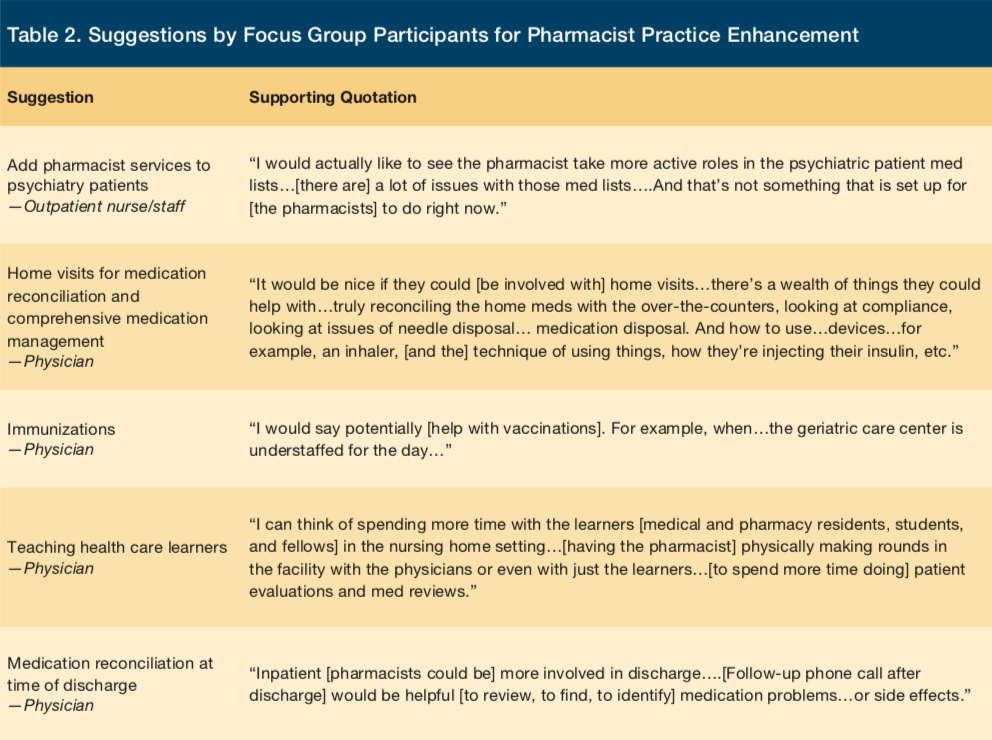

In addition, there were a number of other helpful suggestions given by the participants. These suggestions for improvement did not fit into a general theme but were instead dependent on the location of practice and professional degree of the participant. A list of requested enhancements is provided in Table 2.

Discussion

Our study illustrates that the pharmacist increases the perceived quality of care for older adults while positively affecting the workload of the health care team. This is especially key in the delivery of geriatric care, an area for which interprofessional teams have been advocated.12

While pharmacists have been shown to impact quality, our care strategy incorporates the pharmacist into direct patient care across various settings, which balances the work of physicians and staff.6,13-15 Our approach to care aligns with national efforts12 and strengthens current pharmacist practice with pharmacists interacting directly with patients, families, and physicians at the time of shared decision making. This allows individualized and detailed care plans to be compiled by pharmacists that may not occur otherwise, as pointed out by staff and physicians. The ability to provide this comprehensive and coordinated care, not only in one setting but continually as patients transition among various levels of care, affords patients and families higher-quality and less-segmented care.4,12,16 This is particularly important as transitions of care are recognized as a major safety risk point for drug therapy problems, communication errors, and hospital readmissions.2-5,17,18 The workload burden created during transitions often falls on the physicians and nursing care staff who already have numerous demands on their time.5,19,20

Requests for increased consistency in the pharmacists’ communication and presence arose as a theme. Throughout the many facilities and levels of care, each patient has a separate medical record and documentation system. Pharmacists currently only have privileges for documentation in the permanent medical record in select settings. Therefore, communication between the pharmacist and other providers often needs to occur using innovative mechanisms that ensure protection of patient data and timeliness. This is especially true in the nursing facility, where slow adoption of the electronic health record requires additional effort to straddle the paper and electronic worlds.21 In our practice, the pharmacists are adept at using multiple medical record systems encountered in nursing facilities and are able to identify and close gaps that often occur between settings. Their familiarity with using the various record systems increases their optimization of medication therapy, but communication of these problems can still be difficult. Among all settings, this communication process is a workflow add-on and therefore perceived as burdensome by both the pharmacist and physician. Constraints on pharmacists’ documentation are a significant barrier to efficient interprofessional communication and subsequent quality of patient care. Currently, team members need to use additional methods (eg, encrypted email, phone) to seek the recommendations. Having the pharmacists’ documentation align with the physicians’ and other team members’ would streamline the communication process and improve workflow, while still allowing them to take the extra step to fill in information gaps.

Face-to-face time between disciplines during patient care visits is a cornerstone of our interprofessional team. This attention by our providers can affect patient flow and often poses a challenge when trying to meet in a timely fashion before drug therapy problems occur. One solution to this is increasing the ratio of pharmacist to physicians to have a more consistent presence of the pharmacist in each location. This would allow for additional direct patient care follow-up and physician overlap time. With this consistency in documentation and additional time spent, improved communication of drug therapy problems could occur.

Our results promote a call to action for pharmacist practice expansion within the geriatric team and into other chronic disease states to create a more robust medical home approach to care. Chronic care management is a major focus of national initiatives and will only increase with the aging population.19,20,22,23 While other advanced practice providers have been identified in chronic care management, pharmacists in our practice are filling this gap and are well positioned to do so as medication experts.23-25 Geriatric-focused patient care naturally centers around medication misadventures at the time of care transitions. Specific requests from focus group participants included well-defined involvement in the inpatient hospital discharge process and the creation of smoother transitions. This is a natural fit for our pharmacists as they practice in all of the levels of the health care system to provide warm handoffs to the next physician-pharmacist team at the time of transition.

Although the inpatient hospital discharge process was identified as an area that needs more pharmacist involvement, the receiving facility in the patient transition is the primary beneficiary when continuity of care is improved. The SNF benefits when the hospital discharge details, including medications, are accurate and clear. Intentional and unintentional medication changes regularly occur in the hospital and reconciling and resolving these present a challenge to the nursing facility.17 Boockvar and colleagues17 showed that medications discontinued or changed can lead to adverse drug events that occur in the nursing facility. Having a medication expert who can assess for safety and appropriateness and make corresponding changes during the hospital to nursing facility transition provides a highly valued service in our practice.

There are two major limitations in this study. The focus group participants’ answers only reflect actions of two specific pharmacists. Without a larger sample of pharmacists to provide more various practice habits and styles, the results may vary when applied to other practices, limiting the generalizability to all pharmacists. However, our findings provide a transferable template for practices that may be expanded and customized to other settings and populations. Also, there was no formal assessment for saturation of participants’ comments collected among the three focus groups. Therefore, saturation of perceptions may not have been achieved.

Conclusion

Balancing the ideal integration and role of the pharmacist on the interprofessional team with cost justification for additional positions is an ongoing regional and national conversation.12,26,27 Our pharmacist practice adds perceived benefits to the care of older adults by improving quality while decreasing work burden of staff and providers. This aligns with health care initiatives focusing on the provision of comprehensive and effective patient care to older adults by interprofessional teams.

References

1. American Geriatrics Society. Prevention is the foundation of geriatric care. www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/Adv_Resources/Preventive_Medicine_Fact_Sheet.pdf. Published March 2013. Accessed June 23, 2017.

2. LaMantia MA, Scheunemann LP, Viera AJ, Busby-Whitehead J, Hanson LC. Interventions to improve transitional care between nursing homes and hospitals: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):777-782.

3. The Joint Commission. Hot topics in health care: transitions of care: the need for a more effective approach to continuing patient care. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/hot_topics_transitions_of_care.pdf. Published June 2012. Accessed June 23, 2017.

4. Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of care consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;4(6):364-370.

5. National Transitions of Care Coalition. Improving transitions of care: the vision of the National Transitions of Care Coalition. https://www.ntocc.org/Portals/0/PDF/Resources/PolicyPaper.pdf. Published May 2008. Accessed June 23, 2017.

6. Kirkham HS, Clark BL, Paynter J, Lewis GH, Duncan I. The effect of a collaborative pharmacist-hospital care transition program on the likelihood of 30-day readmission. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(9):739-745.

7. Steurbaut S, Leemans L, Leysen T, et al. Medication history reconciliation by clinical pharmacists in elderly inpatients admitted from home or a nursing home. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(10):1596-1603.

8. Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. The patient-centered medical home: integrating comprehensive medication management to optimize patient outcomes. www.pcpcc.orghttps://s3.amazonaws.com/HMP/hmp_ln/imported/media/medmanagement.pdf. Published June 2012. Accessed June 23, 2017.

9. Sakely H, Corbo J, Coley K, et al. Pharmacist-led collaborative practice for older adults. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(8):606, 608-609.

10. Kitizinger J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ. 1995;311 (7000): 299-302.

11. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007; 42(4):1758-1772.

12. Partnership for Health in Aging Workgroup on Interdisciplinary Team Training in Geriatrics. Position statement on interdisciplinary team training in geriatrics: an essential

component of quality health care for older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014; 62(5):961-965.

13. Lee JK, Slack MK, Martin J, Ehrman C, Chisholm-Burns M. Geriatric Patient Care by U.S. Pharmacists in healthcare teams: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(7):1119-1127.

14. Luder HR, Frede SM, Kirby JA, et al. TransitionRx: impact of community pharmacy postdischarge medication therapy management on hospital readmission rate. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2015;55(3):246-254.

15. Murray MD, Young J, Hoke S, et al. Pharmacist intervention to improve medication adherence in heart failure: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):714-725.

16. Cawthon C, Walia S, Osborn CY, Niesner KJ, Schnipper JL, Kripalani S. Improving care transitions: the patient perspective. J Health Commun. 2012;17(supp 3):312-324.

17. Boockvar K, Fishman E, Kyriacou CK, Monias A, Gavi S, Cortes T. Adverse events due to discontinuations in drug use and dose changes in patients transferred between acute and long-term care facilities. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(5):545-550.

18. Manias E, Hughes C. Challenges of managing medications for older people at transition points of care. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2015;11(3):442-447.

19. Østbye T, Yarnall KS, Krause KM, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Michener JL. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):209-214.

20. Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an aging America: Building the health care workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2008.

21. Kruse CS, Mileski M, Alaytsev V, Carol E, Williams A . Adoption factors associated with electronic health record among long-term care facilities: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006615.

22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The State of Aging and Health in America 2013. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2013.

23. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic care management services fact sheet. cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-LearningNetwork-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/ChronicCareManagement.pdf. Published December 2016. Accessed June 26, 2017.

24. Everett CM, Thorpe CT, Palta M, Carayon P, Gilchrist VJ, Smith MA. The roles of primary care PAs and NPs caring for older adults with diabetes. JAAPA. 2014;27(4):45-49.

25. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Primary Care Workforce Facts and Stats. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/primary/pcworkforce/index.html. Updated October 2014. Accessed June 26, 2017.

26. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving Patient and Health System Outcomesthrough Advanced Pharmacy Practice. A Report to the U.S. Surgeon General.Office of the Chief Pharmacist. U.S. Public Health Service. https://www.accp.com/docs/positions/misc/improving_patient_and_health_system_outcomes.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed June 26, 2017.

27. Touchette DR, Doloresco F, Suda KJ, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services: 2006-2010. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(8):771-793.