Examining the Rationale and Processes Behind the Development of AMDA’s Competencies for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care

Full title: Examining the Rationale and Processes Behind the Development of AMDA’s Competencies for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine

Abstract: The link between nursing care and clinical quality has long been recognized, whereas the link between physician care and quality is just starting to be defined. To ensure physicians treating elderly patients in skilled care settings are equipped to care for this population, AMDA – The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine (formerly the American Medical Directors Association) convened a competency work group to develop a set of competencies geared specifically toward the nursing home attending physician. This article outlines these competencies and reviews the rationale and processes behind their development.

Key words: Long-term care, nursing home attending physician competencies, quality of care, quality of life.

Affiliations: 1Baycrest Geriatric Health Center, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada 2Chief Medical Officer, CommuniCare Family of Companies, Cincinnati, OH 3Corporate Medical Director, Life Care Centers of America, Charlottesville, VA 4Family Medicine Physician, CapitalCare Family Medicine, Ballston Spa, NY 5Director of Education, American Medical Directors Association, Columbia, MD

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Nursing homes (NHs) are increasingly recognized as critical components of the long-term care (LTC) continuum. Acute care systems have come to recognize the need for high-quality and easily accessible post-acute care venues, a niche that NHs have embraced over the past several years. In fact, post-acute patients receiving skilled nursing facility rehabilitation now account for almost 20% of total NH days.1 However, this patient population has in recent years increasingly presented with illnesses of greater intensity and complexity, and with greater frailty, than in previous years. This trend presents a challenge for the healthcare professionals who provide care at the bedside.2

Whereas alternatives to NH care clearly exist (ie, home care, assisted living), the capacity to accommodate a burgeoning, frailer, older population will likely strain the system even as it ensures an important role for NHs well into the foreseeable future. Although the prevalence of disability has declined in recent years, there still remains a 46% chance of being admitted to an NH after age 65 years.3 In jurisdictions such as Canada, where bed occupancy is much higher than in the United States, the number of NH beds is projected to increase from 280,000 in 2008 to 690,000 by 2038, fueled in large part by the increasing prevalence of dementia.4

A major concern is whether NHs will be able to accommodate the increased acuity and need of this projected influx of residents. Despite evidence linking nursing staff ratios and educational levels/competencies to quality of care in NHs, staffing remains a major challenge throughout the LTC continuum.5 Only a minority of licensed nurses and physicians have received adequate training in geriatrics or meaningful exposure to LTC practice.6,7 An aging nursing workforce soon heading into retirement portends significant shortages in the coming decades. For nurses already working in NHs, turnover and burnout are significant, with more than 19,000 registered nurse vacancies reported in NHs.8 Nurse staffing ratios (expressed as hours/resident/day) are highly variable between states and in some cases may contribute to a stressful work environment.9

While the evidence linking nursing care to clinical quality is well accepted, an analogous link between physician care and quality is just now being defined. Notably, new evidence suggests that physician commitment (defined as the percentage of total practice devoted to NH care), nurse-to-physician communication, and medical staff organization are all correlated with important clinical outcomes.10-14

Predicated on the need for a skilled provider workforce, as well as additional rationale set forth in a 2010 white paper commissioned by AMDA – The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine (formerly the American Medical Directors Association), a competency work group was convened in 2011. This work group was charged with developing a framework for a set of competencies (ie, measurable or observable knowledge, skills, abilities, and behaviors that are critical to successful job performance) geared specifically toward the NH attending physician. What follows is a review of these competencies and the rationale and processes behind their development.

Framework, Principles, and Scope of Nursing Home Competencies

The rationale for a framework upon which to build NH competencies consisted of the following key points or observations: (1) NH practice demands a unique skill set; (2) competencies should be linked to relevant clinical outcomes/quality; (3) the credibility of physicians should be predicated, in large part, on specialization; (4) there is an impetus to set the bar for standards independently or allow government to determine performance metrics; and (5) competencies should inform new curriculum development, which aligns with the educational mission of AMDA. The framework that resulted was based upon the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Outcome Project’s general domains, which included: (1) foundation (ethics, professionalism, communication); (2) medical care delivery process; (3) systems; (4) nursing home medical knowledge; and (5) personal QAPI (quality assurance and process improvement).

Principles Guiding Competency Development

Three major concepts guided the work group as they developed the core competencies. The first was the acknowledgment that the practice of post-acute and LTC medicine requires a knowledge base and skill set that can be defined within a specific set of competencies and which reflect expertise found in a number of other specialties, including family medicine, internal medicine, hospital medicine,

palliative care, rehabilitation, geriatric medicine, and psychiatry. Second, although none of these discipline-specific competencies are individually sufficient to describe the full range of post-acute and LTC medicine competencies, each one is necessary for effective practice. Third, that competencies must reflect a mix of the many skills unique to each of these disciplines, which must then be operationalized within a unique care setting with its unique regulatory requirements while incorporating the full skill set of the entire interdisciplinary team (IDT).

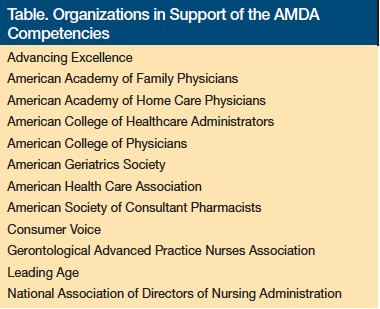

The Developing a Curriculum process was used by the 25-member AMDA work group, and an initial draft of the competencies was developed and reviewed by 450 AMDA members via online survey. Based on this input, the competencies were further revised and then vetted by the following organizations, representing their professions as well as the industry: American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP); American College of Healthcare Administrators; American College of Physicians (ACP); American Geriatrics Society (AGS); American Health Care Association; American Society of Consultant Pharmacists; Leading Age; National Association of Directors of Nursing Administration; and the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM).

AMDA’s Competencies

As previously noted, AMDA’s competencies for post-acute and LTC medicine fall under one of five general domains: foundation, medical care delivery process, systems, medical knowledge, and personal QAPI. Competencies associated with each of these domains are outlined in the sections that follow.

Foundation

Foundation, which focuses on ethics, professionalism, and communication, establishes the following six competencies for the NH attending physician:

1.1 Addresses conflicts that may arise in the provision of clinical care by applying principles of ethical decision-making.

1.2 Provides and supports care that is consistent with (but not based exclusively on) legal and regulatory requirements.

1.3 Interacts with staff, patients, and families effectively by using appropriate strategies to address sensory, language, health literacy, cognitive, and other limitations.

1.4 Demonstrates communication skills that foster positive interpersonal relationships with residents, their families, and members of the interdisciplinary team (IDT).

1.5 Exhibits professional, respectful, and culturally sensitive behavior towards residents, their families, and members of the IDT.

1.6 Addresses patient/resident care needs, visits, phone calls, and documentation in an appropriate and timely fashion.

Medical Care Delivery Process

Medical care delivery process includes the following five competencies:

2.1 Manages the care of all post-acute patients/LTC residents by consistently and effectively applying the medical care delivery process—including recognition, problem definition, diagnosis, goal identification, intervention, and monitoring of progress.

2.2 Develops, in collaboration with the IDT, a person-centered, evidence-based medical care plan that strives to optimize quality of life and function within the limits of an individual’s medical condition, prognosis, and wishes.

2.3 Estimates prognosis based on a comprehensive patient/resident evaluation and available prognostic tools, and discusses the conclusions with the patient/resident, their families (when appropriate), and staff.

2.4 Identifies circumstances in which palliative and/or end-of-life care (eg, hospice) may benefit the patient/resident and family.

2.5 Develops and oversees, in collaboration with the IDT, an effective palliative care plan for patients/residents with pain, other significant acute or chronic symptoms, or who are at the end of life.

Systems

Systems includes the following six competencies:

3.1 Provides care that uses resources prudently and minimizes unnecessary discomfort and disruption for patients/residents (eg, limited nonessential vital signs and blood glucose checks).

3.2 Can identify rationale for and uses of key patient/resident databases (eg, the Minimum Data Set [MDS]), in care planning, facility reimbursement, and monitoring of quality.

3.3 Guides determinations of appropriate levels of care for patients/residents, including identification of those who could benefit from a different level of care,

3.4 Performs functions and tasks that support safe transitions of care.

3.5 Works effectively with other members of the IDT, including the medical director, in providing care based on understanding and valuing the general roles, responsibilities, and levels of knowledge and training for those of various disciplines.

3.6 Informs patients/residents and their families of their healthcare options and potential impact on personal finances by incorporating knowledge of payment models relevant to the post-acute and LTC setting.

Medical Knowledge

Medical knowledge includes the following six competencies:

4.1 Identifies, evaluates, and addresses significant symptoms associated with change of condition, based on knowledge of diagnosis in individuals with multiple comorbidities and risk factors.

4.2 Formulates a pertinent and adequate differential diagnosis for all medical signs and symptoms, recognizing atypical presentation of disease, for post-acute patients and LTC residents.

4.3 Identifies and develops a person-centered medical treatment plan for diseases and geriatric syndromes commonly found in post-acute patients and LTC residents.

4.4 Identifies interventions to minimize risk factors and optimize patient/resident safety (eg, prescribes antibiotics and antipsychotics prudently, assesses the risks and benefits of initiation or continuation of physical restraints, urinary catheters, and venous access catheters).

4.5 Manages pain effectively and without causing undue treatment complications.

4.6 Prescribes and adjusts medications prudently,consistent with identified indications and known risks and warnings.

Personal QAPI

Personal QAPI includes the following three competencies:

5.1 Develops a continuous professional development plan focused on post-acute and LTC medicine, utilizing relevant opportunities from professional organizations (AMDA, AGS, AAFP, ACP, SHM, American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine), licensing requirements (state, national, province), and maintenance of certification programs.

5.2 Utilizes data (eg, Physician Quality Reporting System indicators, MDS data, patient satisfaction) to improve care of their patients/residents.

5.3 Strives to improve personal practice and patient/resident results by evaluating patient/resident adverse events and outcomes (eg, falls, medication errors, healthcare-acquired infections, dehydration, rehospitalization).

Next Steps

Presently, support for the post-acute and LTC competencies is being solicited by several stakeholder organizations. A list of the organizations that, to date, have signed on with formal support is provided in the Table. In addition, AMDA’s education committee has constituted a work group to develop a curriculum specific to the competencies as well as to define metrics for each of the skill sets defined by the competency statements.

It is important to note that the goal of the competency initiative is to define the skills necessary for effective and high-quality practice in the NH, and not to create barriers to practice. Although a certification process may evolve in the future—an American Medical Director Certification Program work group has recently been constituted to explore this issue—the primary intent is to recognize and further professionalize NH practice. The need to recruit thousands of new NH practitioners is paramount if we are to accommodate the demographic imperatives presented by our aging population. Whether it is for the community-based primary care provider or the post-acute–oriented hospitalist, AMDA is committed to delivering the education necessary to prepare physicians for the complexities and challenges that constitute the contemporary NH setting. To that end, AMDA plans to conduct rigorous evaluation of the competencies to demonstrate their impact on relevant clinical outcomes recognizing that, at present, they are not evidence-based.

References

1. Tyler DA, Feng Z, Leland NE, Gozalo P, Intrator O, Mor V. Trends in postacute care and staffing in US nursing homes, 2001-2010. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(11):817-820.

2. Plotzke M, White A. Differences in resident case mix between Medicare and non-Medicare nursing home residents. A report by Abt Associates for the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Published October 2009. Accessed August 29, 2014.

3. White A, Rowan P. Differences in resident case mix between Medicare and non-Medicare nursing home residents. A report by Abt Associates for the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Published March 2013. Accessed August 29, 2014.

4. Spillman BC, Lubitz J. New estimates of lifetime nursing home use: have patterns of use changed? Med Care. 2002;40(10):965-975.

5. Rising tide: the impact of dementia on Canadian society. Alzheimer Society of Canada. www.alzheimer.ca/~/media/Files/national/Advocacy/ASC_Rising_Tide_Full_Report_e.pdf. Updated February 26, 2014. Accessed March 18, 2014.

6. Castle NG. Nursing home caregiver staffing levels and quality of care: a literature review. J Appl Gerontol. 2008;27(4):375-405.

7. Gilje F, Lacey L, Moore C. Gerontology and geriatric issues and trends in US nursing programs: a national survey. J Prof Nurs. 2007;23(1):21-29.

8. Diachun L, Van Bussel L, Hansen KT, Charise A, Rieder MJ. “But I see old people everywhere”: dispelling the myth that eldercare is learned in nongeriatric clerkships. Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1221-1228.

9. Nursing shortage. American Association of Colleges of Nursing website. www.aacn.nche.edu/media-relations/fact-sheets/nursing-shortage. Updated January 21, 2014. Accessed March 18, 2014.

10. Harrington C, Choiniere J, Goldmann M, et al. Nursing home staffing standards and staffing levels in six countries. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;44(1):88-98.

11. Katz PR, Karuza J, Intrator O, Mor V. Nursing home physician specialists: a response to the workforce crisis in long-term care. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(6):411-413.

12. Young Y, Inamdar S, Dichter BS, Kilburn H Jr, Hannan EL. Clinical and nonclinical factors associated with potentially preventable hospitalizations among nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(5):364-371.

13. Katz PR, Karuza J, Lima J, Intrator O. Nursing home medical staff organization: correlates with quality indicators. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(9):655-659.

14. Kuo YF, Raji MA, Goodwin JS. Association between proportion of provider clinical effort in nursing homes and potentially avoidable hospitalizations and medical costs of nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(10):1750-1757.

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to: Sheena Majette, BS, American Medical Directors Association, 11000 Broken Land Parkway, Suite 400, Columbia, MD 21044; smajette@amda.com