Evaluating Measures and Instruments for Quality Improvement in Assisted Living

Assisted living (AL) has been in evolution since the 1940s. Now more than ever, AL providers must address the quality of their services and care in light of variations across settings, increased resident acuity, and changes spurred by health care reform. Unfortunately, quality improvement is hindered because few providers are aware of valid and reliable tools (measures and instruments) that have been used in AL or other health and long-term care settings that serve similar populations. This project conducted a comprehensive environmental scan and critique of tools applicable for quality improvement in AL in five domains. A peer-reviewed literature search generated 9048 relevant citations, and a grey literature search generated 361 relevant sources and 51 websites, ultimately identifying 254 tools. After critiquing all tools in relation to their psychometric properties and utility for quality improvement in AL, 96 are recommended for use to improve person-centered care (6 tools), medication management (10), care coordination/transitions (17), resident/patient outcomes (35), and workforce (28). A gap analysis indicated a need to develop tools to assess staff sufficiency and overall quality.

Key words: person-centered, medication management, care coordination/transitions, resident/patient outcomes, workforce, psychometrics

Historically, the intent of assisted living (AL) has been to promote the dignity and independence of older adult residents.1 Today, AL providers care for residents with more health and support needs than ever before.2 As a consequence, AL has become recognized as a potentially viable component of managed and accountable care organizations in the provision of health care for older adults.3,4

If AL providers are to have a more recognized role in health care, they must embrace the use of quality metrics to guide quality improvement initiatives.5 Tools (measures and instruments) that assess structures, processes, and outcomes of care6 allow AL staff and others to better understand the quality of services provided and can help to indicate where improvement may be indicated. Unfortunately, AL providers have been slow to adopt measurement and quality improvement, due in part to a lack of consensus on what and how to measure key quality domains.5

Quality improvement, services, and care in AL must address the needs of the AL resident population. For example, 74% of residents have limitations in activities of daily living, and 94% have chronic health conditions.7 Given the grounding of AL in quality of life—articulated in philosophies such as maximizing independence, promoting individuality, and protecting the right to privacy,1—and now also necessary attention to health care and supportive needs, these five domains are central to quality in AL.

Person-centered care. Concern has been raised that AL care is not as person-centered as intended, “lacking, for example, a focus on relationships, empowered staff…and opportunities for self-worth.”8 Just as person-centered care is important throughout the health care system,9 it must be measured and monitored in AL settings.

Medication management. The most common supportive care need in AL is medication management.10 Concerns that have been raised about medication management for older adults include administration of medications by unlicensed assistive personnel and off-label use of antipsychotic medications, among others.11,12 Due to the ubiquitous need for support with medication management, and the potentially serious consequences of inappropriate care, it is important that this be a target for quality monitoring.

Care coordination/transitions. Almost one-third of AL residents are hospitalized annually, and one-quarter visit an emergency department.5 Also, 15% die or move to a nursing home,13 underscoring the prevalence of transitions. Avoidable re-hospitalizations are a concern, and care coordination to reduce transfers has been effective in nursing homes;14 given the extent of chronic health conditions and health care use in AL, there is need to attend to care coordination and transitions in this population.

Resident/patient outcomes. Processes of care–including those above–are important because they affect outcomes. Poor care may result in worse quality of life,15 medication side effects,16 and hospitalization/re-hospitalization.9 The intent of quality improvement is to promote better resident outcomes, and so it is important they be monitored.

Workforce. The sufficiency and quality of the workforce that provides support and care to AL residents plays an important role in outcomes. For example, consistent staffing is considered important for person-centered care,17 and lower staffing levels and more staff turnover relate to resident and staff outcomes.18 Consequently, it is important to measure and monitor matters related to the workforce when promoting quality in AL.

Because AL quality improvement has been hindered due to unfamiliarity with valid and reliable tools, the aim of this project was to identify and evaluate tools in these five quality domains that have been implemented in AL and other health and long-term care settings, and can be used for quality improvement.

METHODS

We sought to identify tools for assessing quality in the five domains considered central in the AL setting: person-centered care, medication management, care coordination/transitions, resident/patient outcomes, and workforce. The effort included specifying the areas of focus within each domain, conducting literature searches, soliciting feedback from an advisory panel, evaluating the quality of the identified tools/conducting a psychometric analysis, developing recommendations, and undertaking a gap analysis. More details about the methods and results can be found at www.theceal.org.

Because the five domains are broad, the search was limited to four key areas within each domain (ie, 20 areas in total), reflecting topics of importance in previous work (Table 1).

Conducting the Literature Search

Tools were identified through a comprehensive search to identify measures and instruments implemented in specific settings of care related to the four areas within each of the five domains. Sample key words for tools included, among others, “measure,” “instrument,” and “survey;” sample key words for settings of care included “long-term care,” “AL,” “residential care,” “dementia care,” “nursing home,” “hospital,” and others. Sample key areas for words within each domain were also developed, and additional criteria for inclusion were specified (Box 1).

A research librarian created every possible combination of search terms related to tools, settings, and domains/key areas and searched databases of peer-reviewed literature (Cochrane, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health, Health and Psychosocial Instruments, PsycInfo, and PubMed) as well as the Grey Literature Reports (New York Academy of Medicine) to identify books, government reports, newspaper articles, press releases, policy reports, and other non peer-reviewed materials. Additional searches used the Google search engine to identify clinical performance guidelines, accreditation standards, quality improvement initiatives, and mission statements of relevant organizations.

Soliciting Feedback From an Advisory Panel

Fourteen individuals with expertise in long-term care and quality measurement served as advisors. Using a nominal group technique, they offered feedback related to inclusion and exclusion criteria, literature search terms, and the initial iteration of tools resulting from the searches.

Evaluating the Quality of the Identified Tools

All tools were critically reviewed in reference to descriptive and psychometric performance characteristics, based on those identified in the COSMIN initiative (Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments)19 and used in similar efforts20,21 and refined for this project. Four health services researchers with expertise in long-term care and AL rated the tool’s psychometric properties and performance characteristics on a 0 to 2 scale, using five items to rate instruments (reliability, validity, interpretability/utility, ease of use, and availability of benchmarks) and two items to rate measures (ease of use and availability of benchmarks). The raters pilot-tested the scoring strategy and met to assure commonality in scoring. Results were entered into a Microsoft Access (version 2013) database.

A total score was generated for each tool using SAS Version 9.4. The raw score of instruments ranged from 0 to 10 (2 points for each of 5 items), and the raw score of measures ranged from 0 to 4 (2 points for each of 2 items). To facilitate comparison, final scores were converted to a 10-point scale, such that a measure score of 2 (of 4) translated to 5 (of 10), and a measure score of 4 (of 4) translated to 10 (of 10).

Developing Recommendations and Undertaking a Gap Analysis

After scores were derived, tools were reviewed with an expert in AL care administration, provision, and policy. Recommendations were made on the basis of the intent of the tool, its score, its comparative advantage over other tools, and, most especially, its utility for AL quality improvement. Additional considerations that drove recommendation include those below.

Individualized nature of AL. Whether a tool is useful for a given AL community depends on the community’s characteristics and resident population. For example, tools that are specific to residents with dementia are useful if a large proportion of residents has cognitive impairment. Recommended tools were those conceivably useful to a range of AL residences.

Scores. Important components of each tool’s score reflect its ease of use and interpretability/utility. Ease of use depends on how the tool is administered in light of a community’s resources, and as above, utility may be setting-specific. In addition, this project may not have not identified all literature related to psychometric properties, which would affect scoring. Consequently, scores were informative, but not used for decision-making in and of themselves.

Domains. Although each tool was identified as assessing one of the five domains, some assess more than one domain (eg, a workforce tool assessing empowerment is also relevant to person-centered care). When recommending a tool, it was considered that users might want a tool that achieves more than one purpose.

Finally, after reviewing all recommended tools, critical consideration was given to what tools would be helpful that were not identified in this scan. Throughout the project, feedback on the methods, results, recommendations, and gap analyses was provided by board members of the Center for Excellence in Assisted Living, a collaborative of 10 diverse national organizations that work together closely to promote excellence in AL.

RESULTS

The peer-reviewed literature search generated 9048 non-duplicative citations; the grey literature search generated 361 sources in addition to websites of 51 organizations. Reviewing all sources, assuring that the tools met eligibility criteria, and omitting duplications resulted in a total of 254 identified tools: 136 measures and 118 instruments. After critical review, 96 tools were recommended for use, including 53 measures and 43 instruments. A detailed description of each of these tools is provided at https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Measures-and-Instruments-for-Quality-Improvement-in-Assisted-Living_Final-Report.pdf.

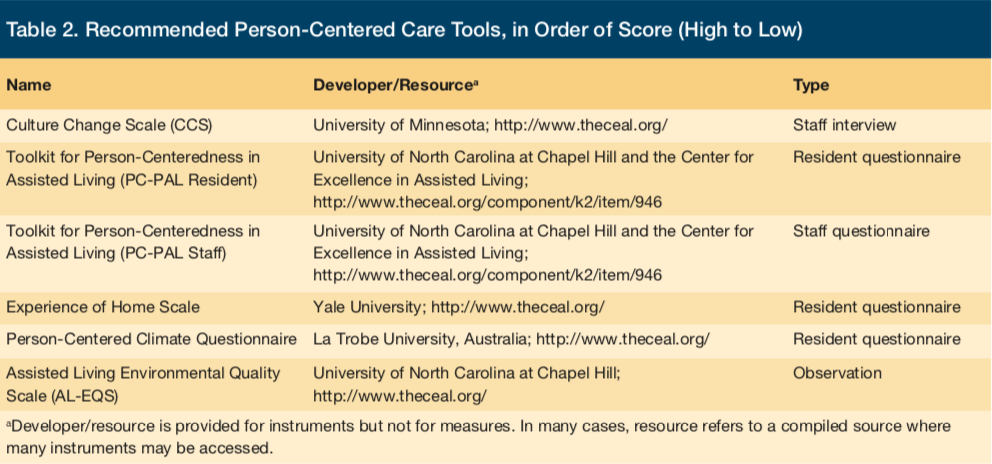

Person-Centered Care

The 22 person-centered care assessment tools largely use interviews or questionnaires with residents, staff, and others, and also observations, to assess structures, processes, and outcomes of person-centered care. Six of these tools are recommended (Table 2). All recommended tools are instruments (ie, based on scales or indices). Only two of the tools—The Toolkit for Person-Centeredness in Assisted Living (PC-PAL), resident and staff version—were developed expressly for AL; they were developed using a collaborative approach that included AL providers, staff, residents, and researchers, and they elicit perceptions from residents (or family proxies) and staff regarding the concepts and items they themselves find important to person-centeredness.8

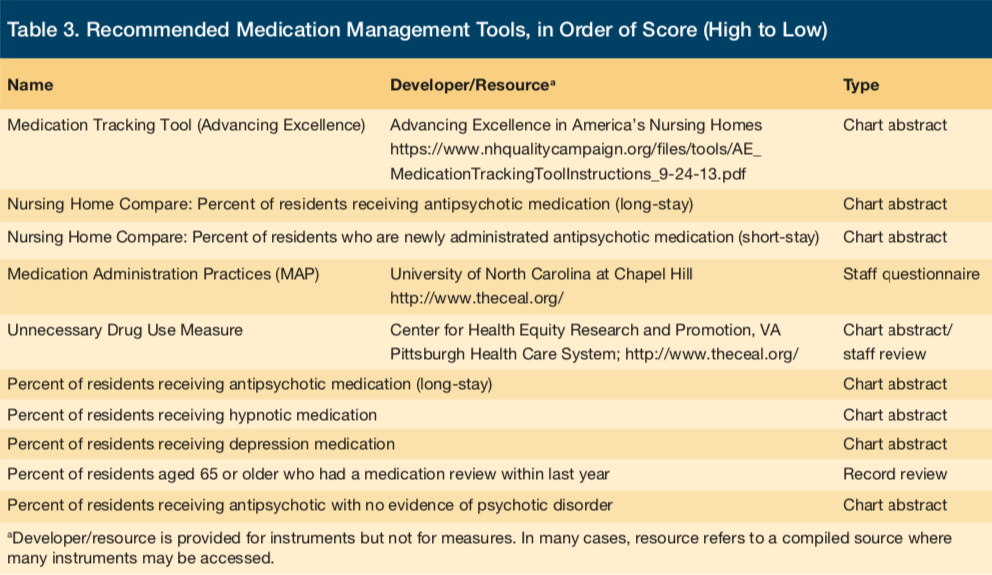

Medication Management

The 24 medication management tools largely use chart abstraction, and also questionnaires with staff, to assess processes and outcomes of medication management. Unlike the person-centered domain, the majority of these tools are measures (ie, counts). The 10 recommended tools (Table 3) include counts of use of antipsychotic, anxiolytic, hypnotic, and antidepressant medications as well as instruments to assess medication administration (for example, the Medication Administration Practices [MAP], which relates to the likelihood to make an administration error)22 and the appropriateness of drug use (for example, the Unnecessary Drug Use Measure, which assesses use based on indication, effectiveness, and therapeutic duplication).23

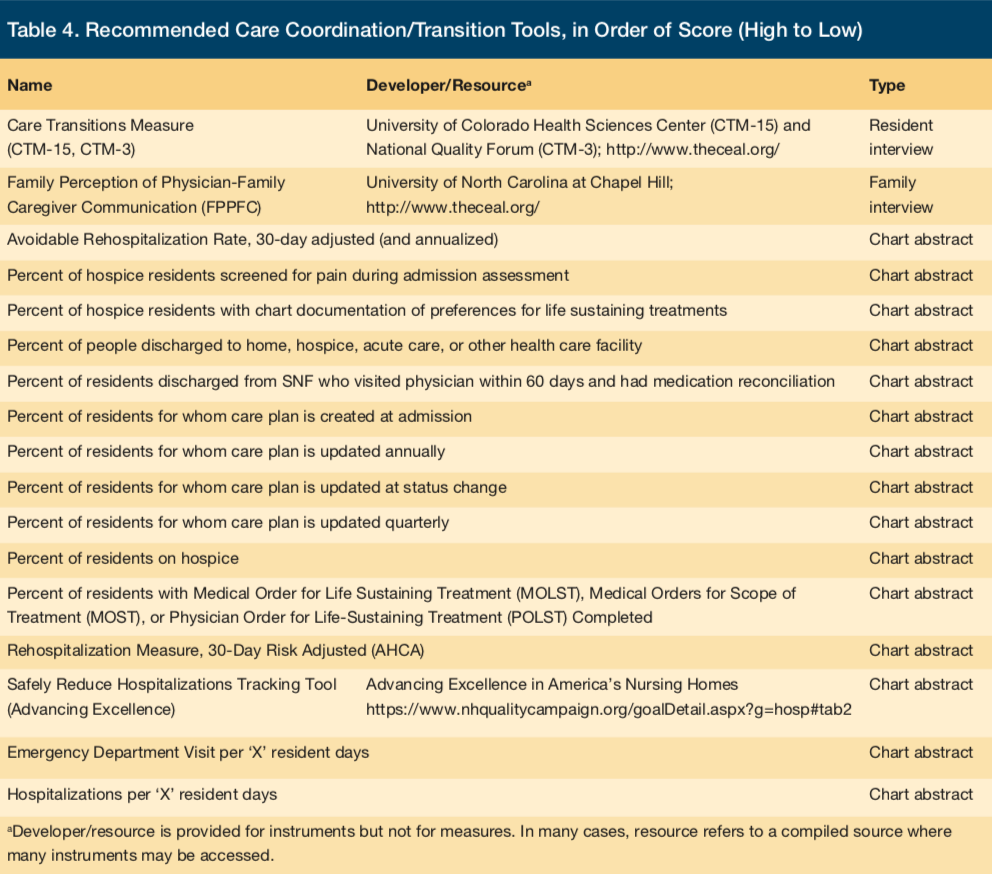

Care Coordination/Transitions

The 32 care coordination/transitions tools we identified, 17 of which are recommended (Table 4), largely use chart abstraction and interviews with residents and families to assess processes and outcomes of care coordination/transitions. Similar to medication management, most are measures, counting events such as hospitalizations, rehospitalizations, emergency department use, discharge, assessment, care planning, and documentation related to preferences for life-sustaining treatments. The two instruments include a Care Transitions Measure (CTM) —the 3-item version of which assesses having preferences taken into account, having a good understanding of how to manage health, and understanding the need for specific medications24—and the Family Perceptions of Physician-Family Caregiver Communication (FPPFC), which assesses communication during the last month of life.25

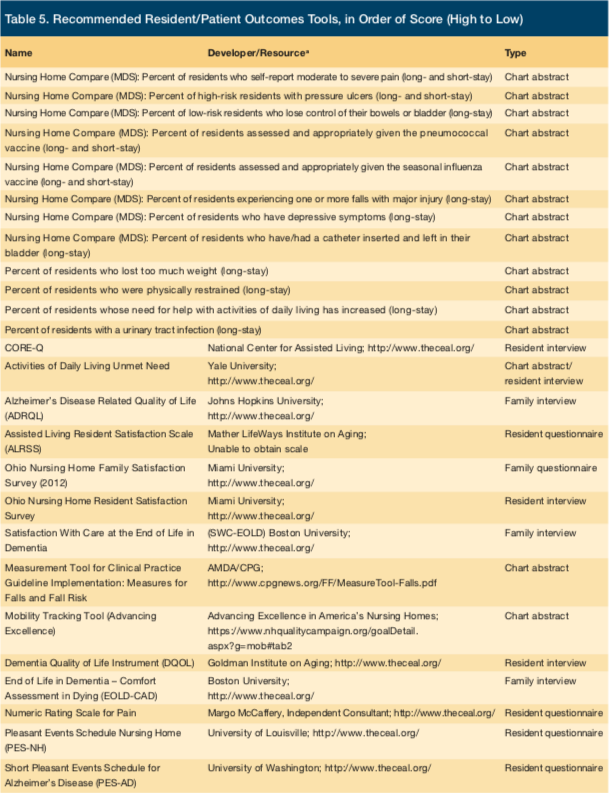

Resident/Patient Outcomes

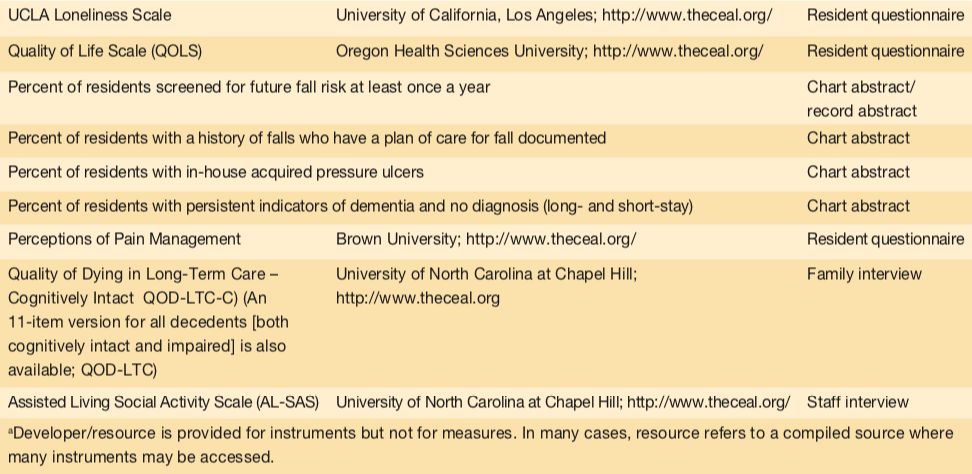

The 69 resident/patient outcome tools largely use interviews or questionnaires with residents and families, as well as chart/record abstraction, to assess outcomes, and to a lesser extent, processes of care. The 35 recommended tools include both measures and instruments, and their large number reflects the numerous outcomes that are relevant for AL residents (Table 5). For example, measures/counts include those of residents in pain, with incontinence, with pressure ulcers, who lost too much weight, were restrained, or received preventive vaccines, among other areas. Instruments include the CORE-Q, developed by the National Center for Assisted Living, which assesses satisfaction related to the AL residence, staff, care, and food,26 and instruments assessing quality of life, end-of-life care, pleasant events, social activity, loneliness, as well as other areas.

Workforce

The 107 workforce tools largely use interviews or questionnaires with staff, as well as record abstraction, to assess structures, processes, and outcomes related to the workforce. The 28 recommended tools include measures and instruments (Table 6). Measures assess consistent assignment (the Advancing Excellence Consistent Assignment Tracking Tool, an on-line resource)27 and turnover (the Eaton Instrument for Measuring Turnover, the ratio of new employees to total employees, by category)28 as well as the number of registered and licensed nurses and the percentage of specialists who have geriatric certification or training. Instruments include the Perception of Empowerment Instrument, which assesses perception of worker autonomy, responsibility, and participation,29 and others assessing supervision, leadership, job quality and barriers, grief support, and burnout, among other areas.

DISCUSSION

AL is increasingly being considered a viable care option among integrated care models,4 and tools to assess and promote quality may be central toward that effort. This project was done to identify such tools that may be used to guide quality improvement efforts in AL. Identifying these tools serves five key purposes: (1) it informs stakeholders how providers are measuring care and outcomes; (2) it facilitates access to quality assessment tools; (3) it paves the way for the use of similar tools across a range of providers; (4) it allows providers who use these tools to monitor and improve services and outcomes, and (5) when information is shared, it notifies others as to those services and outcomes.

The project uncovered 254 tools, and recommended 96, that are potentially useful for quality improvement in AL. These tools have not all been developed for or used in AL necessarily; in fact, with few exceptions (eg, the PC-PAL), most derive from other health and long-term care settings, including nursing homes. The relevance of tools used in other settings is not meant to convey that the settings themselves are identical, but rather that the AL resident population has some similarities to other resident populations. For example, falls, dementia, and other chronic conditions are common among older adults across residence types; rising acuity in AL has become a notable focus;30 and concern has been raised about antipsychotic use in AL.31 Therefore, the use of relevant outcome tools designed in other settings with older adult resident populations is justified.

In fact, of the five domains examined in this work, all except person-centered care lend themselves to the use of tools developed in other settings (albeit sometimes needing minor modification, such as omitting the word “hospice” from the measure that derives the “percent of hospice residents screened for pain”). Because AL differs from other settings, issues related to person-centeredness may best be captured by a setting-specific tool; the PC-PAL, developed by the authors and funders of this review, is currently the only known such tool.

Some may question the wisdom of recommending 96 tools, given that the sheer number may create a challenge to select tools for actual use. However, the tools themselves are not duplicative; instead, each assesses something different and/or uses different items. Given notable variability among AL residences (eg, they range from 4 to more than 200 beds, which relates to the types of services they provide32), the range of tools allows providers to identify those that are most relevant to their population, organizational characteristics, mission, and quality improvement goals. Further, the full utility of the tools may best be realized by using some in combination. For example, it does little good to assess pain if practices are not in place to manage pain and monitor success.

No tools were considered to be suitable to assess the sufficiency of staffing. That is, calculating the number of direct care workers and nurses is of little utility when resident acuity is as variable as it is among AL residents and across communities. In nursing homes, acuity is determined according to standardized Resource Utilization Groups,33 which can determine staffing needs. No such indicators exist for AL, making it challenging to determine whether staffing is adequate to meet resident needs.

A second area that could benefit from additional tool development is an overall measure of quality, akin to the Five-Star Quality Rating System used in nursing homes.34 There has already been discussion of the benefit of public reporting for AL,35 and states including North Carolina have developed a Star Rating Program.36

It is important to note that, despite the scope of this effort, some potentially useful tools may have been missed, and staff at some AL communities may choose to use tools other than those recommended herein.

Of course, the availability of tools does not suggest that AL staff necessarily have the capacity to use them—a point driven home by national data indicating that fewer than 20% of AL communities have electronic health records4 (and, therefore, the capacity for electronic monitoring). Therefore, assistance may be necessary for AL providers to understand the existing tools, access them, administer them, score them, and take action based on the results. Such efforts may be facilitated by national organizations and local providers and consultants.

1. Assisted Living Quality Coalition. Assisted Living Quality Initiative: building a structure that promotes quality. Washington, DC: American Association of Retired Persons Public Policy Institute; 1998.

2. Zimmerman S, Gruber-Baldini AL, Sloane PD, et al. Assisted living and nursing homes: apples and oranges? Gerontologist. 2003;43(spec no 2):107-117.

3. Avalere Health. Vantage Care Positioning System. Assisted living facilities: an untapped opportunity in the quest to achieve the Triple Aim. February 2013 Strategic Focus Research Report. http://hcr-mag.com/documents/Assisted%20Living%20Facilities%20-%20An%20Untapped%20Opportunity%20in%20the%20Quest%20to%20Achieve%20the%20Triple%20Aim.pdf. Published February 2013. Accessed September 30, 2016.

4. Grabowski DC, Caudry DJ, Dean KM, Stevenson DG. Integrated payment and delivery models offer opportunities and challenges for residential care facilities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1650-1656.

5. Center for Excellence in Assisted Living. The future of assisted living in the era of healthcare reform. Summary report. http://www.theceal.org/images/white-papers/CEAL-White-Paper-Formatted-FINAL-033115v3.pdf. Published April 1, 2015. Accessed May 29, 2016.

6. Donabedian A. The quality of care: How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743-1748.

7. Gimm G, Kitsantas P, Cantiello J, Carle A. Resident characteristics and chronic health conditions in assisted living communities. Seniors Hous Care J. 2014;22(1):82-96.

8. Zimmerman S, Allen J, Cohen L, et al. A measure of person-centered practices in assisted living: The PC-PAL. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(2):132-137.

9. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person-Centered Care. Person-centered care: A definition and essential elements. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):15-18.

10. Hawes C, Phillips C. High service or high privacy assisted living facilities, their residents and staff: results from a national survey. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; November 2000.

11. Center for Excellence in Assisted Living. A White Paper from an expert symposium on medication management in assisted living. http://www.ahcancal.org. Published 2008. Accessed May 29, 2016.

12. American Health Care Association. Antipsychotics. www.ahcancal.org Website. http://www.ahcancal.org/quality_improvement/qualityinitiative/Pages/Antipsychotics.aspx. Accessed May 29, 2016.

13. Phillips CD, Hawes C, Spry K, Rose M; prepared for US Department of Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy. Residents leaving assisted living: descriptive and analytic results from a national survey. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/73051/alresid.pdf. Published June 2000. Accessed May 29, 2016.

14. Ouslander JG, Bonner A, Herndon L, Shutes J. The Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) quality improvement program: an overview for medical directors and primary care clinicians in long term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(3):162-170.

15. Kane RA, Lum TY, Cutler LJ, Degenholtz HB, Yu TC. Resident outcomes in small-house nursing homes: a longitudinal evaluation of the initial Green House program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(6):832-839.

16. Lane SJ, Troyer JL, Dienemann JA, Laditka SB, Blanchette CM. Effects of skilled nursing facility structure and process factors on medication errors during nursing home admission. Health Care Manage Rev. 2014;39(4):340-351.

17. Kaldy J. The ties that bind: consistent assignment gives residents a sense of security, family. Provider. 2011;37(6):26, 28.

18. Spilsbury K, Hewitt C, Stirk L, Bowman C. The relationship between nurse staffing and quality of care in nursing homes: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(6):732-750.

19. Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):737-745.

20. Beattie M, Lauder W, Atherton I, Murphy DJ. Instruments to measure patient experience of health care quality in hospitals: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2014;Jan 4(3):4.

21. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. CAHPS: Surveys and tools to advance patient-centered care. http://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/index.html. Updated March 2016. Accessed May 29, 2016.

22. Zimmerman S, Love K, Sloane PD, et al. Medication administration errors in assisted living: scope, characteristics, and the importance of staff training. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(6):1060-1068.

23. Suhrie EM, Hanlon JT, Jaffe EJ, Sevick MA, Ruby CM, Aspinall SL. Impact of a geriatric nursing home palliative care service on unnecessary medication prescribing. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7(1):20-25.

24. The National Quality Forum. Specifications for the Three-Item Care Transition Measure—CTM-3. https://mhdo.maine.gov/_pdf/NQF_CTM_3_%20Specs_FINAL.pdf. Accessed July 3, 2016.

25. Biola H, Sloane PD, Williams CS, Daaleman TP, Williams SW, Zimmerman S. Physician communication with family caregivers of long-term care residents at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(6):846-856.

26. National Center for Assisted Living. Customer Satisfaction. CoreQ. https://www.ahcancal.org/ncal/quality/qualityinitiative/pages/customer-satisfaction.aspx#coreq. Accessed July 3, 2016.

27. Advancing Excellence in America’s Nursing Homes. Consistent Assignment: Follow These Seven Simple Steps to Sucess. https://www.nhqualitycampaign.org/goalDetail.aspx?g=ca. Accessed July 3, 2016.

28. ASPE, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Measuring long-term care work: a guide to selected instruments to examine direct care worker experience and outcomes. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/measuring-long-term-care-work-guide-selected-instruments-examine-direct-care-worker-experiences-and-outcomes. Published April 1, 2005. Accessed July 3, 2016.

29. Advancing Excellence in America’s Nursing Homes. Perception of Empowerment Instrument (PEI). https://www.nhqualitycampaign.org/files/PEI_Instrument.pdf. Published 2002. Accessed July 3, 2016.

30. Gluckstern L. Be prepared for higher acuity in assisted living. Provider. http://www.providermagazine.com/archives/2013_Archives/Pages/0413/Be-Prepared-For-Higher-Acuity-In-Assisted-Living.aspx. Published April 2013. Accessed July 4, 2016.

31. Zimmerman S, Scales K, Wiggins B, Cohen L, Sloane, PD. Addressing antipsychotic use in assisted living residents with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(9):1970-1971.

32. Park-Lee E, Caffrey C, Sengupta M, Moss AJ, Rosenoff E, Harris-Kojetin LD. Residential care facilities: A key sector in the spectrum of long-term care providers in the United States. NCHS Data Brief No 78. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011.

33. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Nursing Home Resident Assessment Resource Utilization Groups. OEI-02-99-00041. Published January 2001. Accessed May 29, 2016.

34. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Five-Star Quality Rating System. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/provider-enrollment-and-certification/certificationandcomplianc/fsqrs.html. Updated May 25, 2016. Accessed May 29, 2016.

35. Zimmerman S, Cohen L, Horsford C. Group proposes public reporting for assisted living. Provider. http://www.providermagazine.com/archives/2013_Archives/Pages/1213/Group-Proposes-Public-Reporting-For-Assisted-Living.aspx. Published December 2013. Accessed July 4, 2016.

36. North Carolina Division of Health Service Regulation. Adult Care Licensure Section. Star Rating Program. https://www2.ncdhhs.gov/dhsr/acls/star/. Updated October 25, 2010. Accessed May 29, 2016.

37. Koren MJ. Person-centered care for nursing homes residents: the culture-change movement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(2):312-317.

38. CHAMP. Geriatric Medication Management Toolkit. CHAMP Website. http://www.champ-program.org. Published 2009. Accessed May 29, 2016.

39. Young HM, Gray SL, McCormick WC, et al. Types, prevalence, and potential clinical significance of medication administration errors in assisted living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7): 1199-1205.

40. National Transitions of Care Coalition. Transitions of Care Measures. Paper by the NTOCC Measures Work Group, 2008. www.ntocc.org. http://www.ntocc.org/Portals/0/PDF/Resources/TransitionsOfCare_Measures.pdf. Published 2008. Accessed May 29, 2016.

41. Frytak JR, Kane RA, Finch MD, Kane RL, Maude-Griffin R. Outcome trajectories for assisted living and nursing facility residents in Oregon. Health Serv Res. 2001;36(1 Pt 1):91-111.

42. Hedrick SC, Sales AE, Sullivan JH, et al. Resident outcomes of Medicaid-funded community residential care. Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):473-482.

43. Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Eckert JK, et al. How good is assisted living? Findings and implications from an outcomes study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60(4):S195-S204.

44. Giuliani CA, Gruber-Baldini AL, Park NS, et al. Physical performance characteristics of assisted living residents and risk for adverse health outcomes. Gerontologist. 2008;48(2):203-212.

45. Stone RI. The long-term care workforce: From accidental to valued profession. in Universal Coverage of Long-Term Care in the United States: Can We Get There from Here? Wolf D, Folbre N, eds. Chapter 8. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2012.

46. Zimmerman S, Williams CS, Reed PS, et al. Attitudes, stress and satisfaction of staff who care for residents with dementia. Gerontologist. 2005;45 Spec No 1(1):96-105.