eINTERACT: The Effect of Health Information Technology on Nurse-to-Provider Communication and Avoidable Hospital Transfers

This quality improvement project incorporated eINTERACT clinical decision support tools into the electronic health record at two subacute rehabilitation centers in New Jersey in an effort to enhance nurse-to-provider communication and reduce avoidable hospital transfers. Pre-and post-implementation survey scores were compared to determine the direction and strength of changes in communication between nursing staff and providers. Qualitative responses were examined through in-vivo coding and categorization of individual experience. Avoidable hospital transfers were measured through retrospective review of rehospitalization rates. Post-implementation survey results indicated positive perceptions of the clinical decision support tool’s role in improving nurse confidence, organizing conversations with providers, and identifying changes in residents’ conditions. The overall decrease in rehospitalization rate was not statistically significant, however. Despite mixed results, the success of this quality improvement project prompted the introduction of eINTERACT as the standard documentation throughout Genesis Health care subacute rehabilitation centers across the United States.

Key words: clinical decision support tool, eINTERACT, SBAR, hospital readmission risk, communication

All supplemental images are at the end of this article below the references or in the attached PDF.

Thirty-day hospital readmissions are common among residents of subacute rehabilitation (SAR) facilities due to the older age, comorbidity, and frailty of this population.1 Rehospitalization of SAR residents contributes to inefficient care, iatrogenic complications, and subsequent decline of the individual.1,2 Subsequently, health institutions receive less Medicare reimbursement as reparation for potentially avoidable hospital readmissions.3 Nurses and primary care providers of SAR residents can be advocates for timely treatment of high-risk readmission diagnoses.3,4 Clinical decision support tools, integrated into health information technology (HIT), have the potential to improve early identification of change in resident condition, enhance communication, and reduce potentially avoidable hospitalizations.5

This quality improvement project integrated the eINTERACT clinical decision support tool into the electronic health record (EHR) at two SAR centers in New Jersey with an aim to improve nurse-to-provider communication and reduce 30-day rehospitalization rates.

Methods

Review of this project was submitted to the Rutgers University Institutional Review Board (IRB). Additional IRB review by Genesis Healthcare was not required because the quality improvement project would proceed anonymously and did not involve management of human participants.

Settings

Genesis Healthcare, a leading provider of skilled nursing and long-term care (LTC) services, agreed to participate in the project. Genesis uses the geriatric-specific EHR PointClickCare, which allowed for the addition of the eINTERACT clinical decision support tool into the platform.6 The time frame of the project is outlined in Table 1.

Center A was a 200-bed LTC and SAR facility. Its central feature is the pulmonary focus program, which specializes in ventilator and tracheostomy management, as well as recovery from respiratory failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation, and pneumonia. Center A staff recognized the significant role of HIT in promoting timely intervention for their high-risk resident population.7

Center B was an 80-bed LTC and SAR center. Its central feature is specialization in wound care management. The facility oversees a variety of wound care, including pressure ulcers and vascular, and neuropathic wounds.7

Participants

Participants in the project were 62 registered nurses, 32 licensed practical nurses, 9 physicians, 1 nurse practitioner, and 1 physician assistant throughout the two centers. Each participant completed de-identified demographic forms to define years of practice and degree level.

Intervention

All nurses were required to attend live, hour-long education sessions about the eINTERACT EHR assessment tool, and no one refused. The presentation included detailed information regarding the system’s purpose, its outcome measurements, a live demonstration, and a question-and-answer session. Meetings were held for all shifts, including nights and weekends, and refreshments were served. Upon completion of the in-service demonstration, nursing staff received a short pre-implementation survey to measure perceived attitudes toward current nurse-to-provider communication.

Detailed telephone calls were placed to the 10 participating providers to describe the objectives and implementation plan. Providers were notified about the Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) feature, a communication form autogenerated by the program in an effort to organize and streamline nursing call communications regarding change in resident condition. Providers were asked to complete a short pre-implementation survey to measure how current communication practices have influenced their decision to transfer potentially unstable residents to the emergency department.

eINTERACT Program

The eINTERACT program was uploaded into PointClickCare software by the center’s information technology department. This EHR combined 5 clinical decision support components used in the INTERACT II paper system.5

Component 1. On the EHR dashboard home page, a “stop and watch” feature notified nursing staff and providers of perceived changes in resident condition (Supplemental Image 1). This tool, completed by nursing staff, quickly identified residents needing closer supervision over the next 24 hours. A change in condition was defined by physical and nonphysical characteristics. Physical changes in condition included baseline difference in bowel or bladder patterns, functional ability, skin changes, shortness of breath, falls, level of weakness, and unstable vital signs. Nonphysical changes to identify involved alterations in eating habits, confusion, agitation, pain, and speech. The alert notified center-affiliated nurses and providers of necessary further evaluation.5

Component 2. The care path assessment form allowed nursing staff to fully document perceived changes in resident condition (Supplemental Image 2). The feature pulled information from the EHR, such as allergies, recent weight, vital signs, and known diagnoses, to aid in timely completion. The assessment page offered algorithms to guide work-ups of common conditions, such as fever, urinary tract infection, respiratory issues, gastrointestinal disturbances, falls, and delirium (Image 1). Upon completion of the assessment, notification alerts directed nurses to recommended timing of provider notification (eg, an urgent need requiring immediate follow up vs a condition warranting notification within 12-24 hours).5 Nursing staff was advised that recommendation alerts were guides and did not replace clinical judgment.

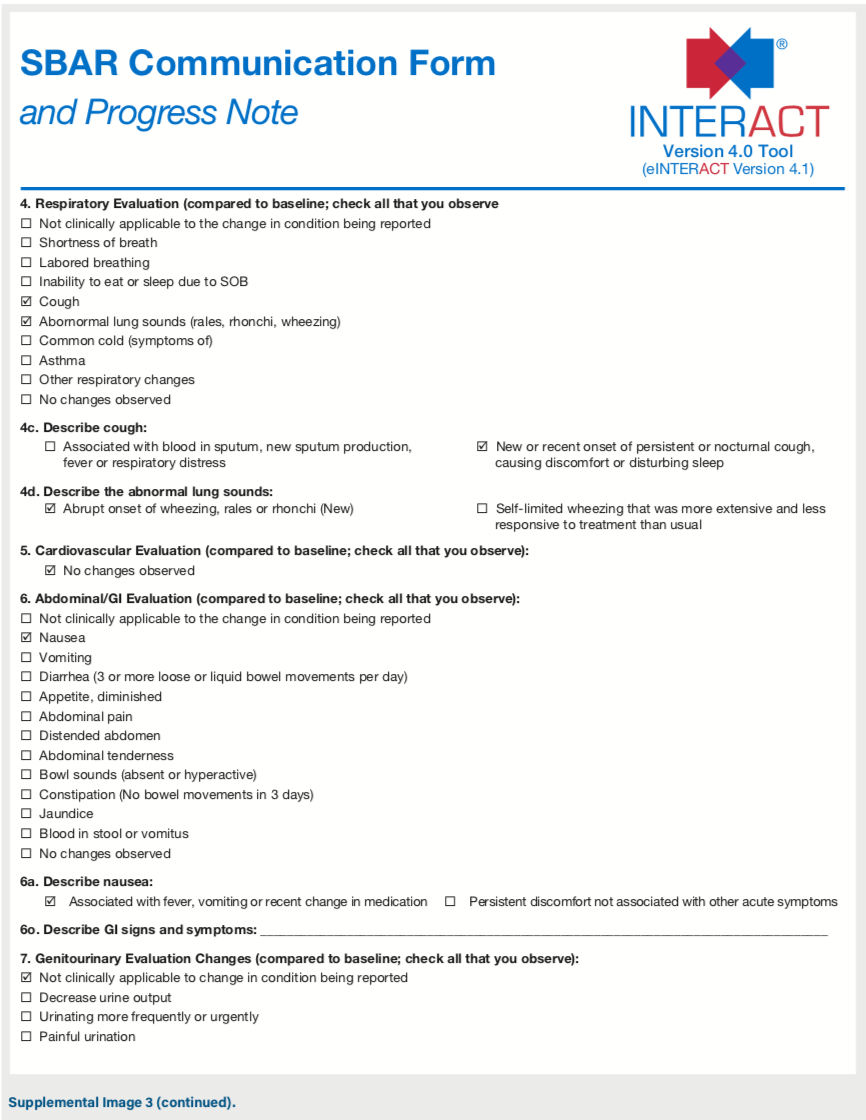

Component 3. Upon completion of the assessment page, the tool autogenerated a SBAR form (Supplemental Image 3). This script, attained from the nurse’s note, provided a structured framework for nurse-to-provider communication.4,5 From this page, the nurse documented notes regarding the discussion and treatment decisions prepared with the primary provider.5

Component 4. In the event of the decision to transfer the resident to the hospital, a resident transfer form was generated. This form ensured organization and inclusion of a complete, resident-specific data assessment. The feature allowed for standardization of transfer information and continuity of information between providers.5

Component 5. Upon completion of the assessment and provider interaction, a quality improvement review tool was generated. This feature was used to investigate transfer events and offered an opportunity for debriefing conversation between staff and providers.5

Measure I: Communication

SurveyMonkey questionnaires were administered to nursing staff and medical providers before and after the quality improvement project (Box 1 and 2). To ensure validity of participant response, these concise questionnaires were adapted from the Renz et al study, which used the Schmidt Nursing Home Quality of Nurse-physician Communication Scale to examine use of the SBAR communication technique and its effect on nurse-to-provider communication.4 Open-ended and Likert surveys were used to determine perceptions on organizational structure, employee confidence, and barriers faced when communicating a resident’s change in condition. Provider questionnaires additionally gauged how communication may influence resident treatment decisions (Box 2).

Measure II: Integration of HIT

The second survey administered after the project measured the feasibility and utility of incorporating HIT into everyday workflow.

Measures III: Resident Outcomes

Resident outcomes were measured through investigation of pre- and post-pilot 30-day rehospitalization rates. Transfer datasets, collected through the PointClickCare EHR hospital transfer portal and census over a 5-month period, were retrospectively examined to compare rates of 30-day hospitalizations to those 1 year prior to the implementation period.

Quality, Security, and Human Subjects Protection

This quality improvement project ensured the control of bias and ethical protection through anonymous use of resident, nursing, and provider data. Nursing and provider online survey results were stored in an encrypted, password-secure website developed by the organization. At the time of data entry, each individual’s pre- and post-pilot questionnaires were deidentified.

Subject Recruitment and Consent

All participants were asked to sign consent forms to provide de-identified demographic data (Supplemental Box 1 and 2). As this was a facility-wide quality improvement project, staff were required to participate in the live demonstration sessions and use of the eINTERACT tool. Staff were assured that all survey results would be presented as de-identified information. Rehospitalization reportable data, from review of PointClickCare’s EHR hospital transfer portal PCC census and Minimum Data Set assessment data, did not have resident names or demographics included in the review. The eINTERACT clinical decision support tool was used for every resident in the facility, and a retrospective review from the previous year’s rehospitalization reports was conducted.

Results

Nurse and Provider Demographics

A total of 57 nursing staff members submitted completed demographic and pre-implementation survey data. Supplemental Table 1 details the demographics of participating nurses, and Supplemental Table 2 lists the demographics of participating providers.

Communication and eINTERACT Utilization

Pre- and post-implementation qualitative data analysis, through in-vivo coding, identified three overarching themes regarding nurses’ opinions of barriers to communication with providers: long-distance communication, condescending providers, and organizational skills. Observations regarding eINTERACT incorporation into everyday workflow addressed the length of the tool, organizational issues, and comfort with experience (Supplemental Table 3 and 4).

Long-distance communication. Difficulties presenting resident case reports to a provider over the phone were recognized as a common barrier to communication (n=8 pre-implementation survey, n=2 post-implementation survey). Several nurses expressed “feeling rushed off of the phone” (n=4) and “feeling there is not enough time to describe my assessment to the provider” (n=1). In addition, nurses expressed concern they were “unable to receive a return call back from the provider” (n=1) and in receiving return calls “in a timely manner” (n=1).

Condescending providers. Several nurses recognized provider manners as an obstacle to effective communication (n=8 pre-implementation survey, n=2 post-implementation survey). Nurses described some physicians as “rude” (n=2) and “condescending” (n=2). However, it was recognized that these interpretations were better “if the provider and nurse have a rapport” (n=1) and if the provider was familiar with the resident in need (n=1). Some nurses felt their years of experience helped in “strengthening my ability to communicate with [a difficult] provider” (n=1). Additionally, organizational tools, such as eINTERACT alongside SBAR, helped prepare some nurses for an impending difficult discussion (n=1).

Organizational skills. Several nurses indicated that eINTERACT improved their data organization prior to speaking with the provider (n=3). As one nurse reported, “The SBAR tool helped organize my assessment before calling the doctor. I felt more organized and prepared.”

Despite success stories, other nurses described organizational obstacles after eINTERACT implementation. Barriers to eINTERACT incorporation into daily workflow included time management skills (n=5), finding the opportunity to document during emergencies (n=5), high acuity assignments (n=2), and busy days (n=1). Nurses struggled with balancing real-time documentation with patient care. As one nurse reported, “It is difficult to document my assessment during my shift. I prioritize patient care over documenting.”

Some 76.7% (n= 46) of nurses identified the length of the eINTERACT assessment tool as a barrier to completion. These nurses responded affirmatively to the question, “Were there times when you felt that the eINTERACT change of condition evaluation was too long, and you needed a shorter tool?” Length of documentation needed for a focused assessment (n=3) was another problem of eINTERACT. As one nurse explained, “[This was a] lengthy form when I wanted to perform a focused assessment, such as change in condition of the skin.”

eINTERACT Integration

While incorporating eINTERACT into everyday workflow met with initial challenges, post-implementation survey results indicated positive perceptions of the clinical decision support tool’s role in identifying change in resident condition. Some 41.7% of nurses (n=25) strongly agreed, and 45% (n=27) agreed, with the statement, “This tool helped me to identify changes in a resident’s condition early on to communicate to the provider.” Regarding the statement, “I feel that the notifications were helpful in determining when to contact the provider,” 52.5% (n=31) of nurses strongly agreed and 35.6% (n=21) agreed. Post-implementation survey results indicated 70% of nurses (n=42) used SBAR information from the tool when calling the provider.

Nurse-to-Provider Quantitative Communication Scores

While qualitative analysis identified particular barriers in communication and eINTERACT operation, the post-implementation survey Likert questionnaire showed favorable results of nurse perception of communicating with providers. All Fischer’s exact chi square models showed significant improvement between pre-implementation Likert scale responses and post-implementation responses (Supplemental Figure 1). The highest difference occurred within participant response to the statement, “I feel nervous before calling the provider to notify him or her of a resident’s change in condition.” Pre-implementation, 30.36% (n=17) of nurses strongly disagreed with the statement. Post-implementation, 61.67% (n=37) of nurses strongly disagreed with the statement (Fischer X2=40.93, P=<.0001).

Provider-to-Nurse Communication

The post-implementation survey questionnaire showed favorable results of provider perceptions of communicating with nurses (Supplemental Figure 2). With the exception of “Information provided to you by nursing, regarding changes in a resident’s status, influenced your clinical decision making for hospitalization of residents,” providers scored the nurses higher in communication post-implementation compared to pre-implementation. The majority of providers strongly agreed that communication did improve after implementation. The percentage of providers who chose ”strongly agree” regarding communication with nurses increased, with the highest increase being 42.86% (Supplemental Figure 2). However, Fischer’s exact chi square models did not show statistical significance between the pre-implementation Likert scale responses and the post-implementation responses, most likely due to the small sample size of providers.

Despite reduced power of the results, 100% of providers responded “more satisfied” to the question “After implementation of the tool, are you more, less, [or unchanged] satisfied regarding nurse-provider communication?”

Resident Outcomes

Overall, there was a decrease in resident 30-day rehospitalization between the pre-and post-implementation periods. The average combined rehospitalization rate during pre-implementation was 16.94%. Post-implementation, the average combined rehospitalization rate was a slightly less 12.71%. Stratifying by location, Center B’s post-implementation rehospitalization rate drove the decrease. Center B’s rehospitalization rate was 18.16% on average during the pre-implementation period and dropped 5.69% after implementation, resulting in an average rehospitalization rate of 12.47%. Contrary to Center B, Center A’s rehospitalization rate increased after implementation. Before implementation, Center A’s average rehospitalization rate was 15.71% and increased to 18.95% after implementation of the project.

Figure 1 details the rate of rehospitalizations over time. Center B’s rehospitalization rate was higher at most points in time compared to Center A’s during the pre-implementation period. Though the rates of each location now appear to be reaching a point of equilibrium, further investigation is needed to understand why rehospitalization rates increased for Center A after implementation.

To determine if there was a true difference attributed to eINTERACT between the pre- and post-implementation rehospitalization rates, a t test was performed. The results showed no significant difference between the average rehospitalization rate before project implementation and after implementation (P=.830, t-value=.27). Therefore, although there was a decrease in the rate of rehospitalization, this finding was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Post-implementation survey results indicated positive perceptions of the clinical decision support tool’s role in improving nurse confidence, organizing conversations with providers, and identifying changes in residents’ conditions. However, the overall decrease in rehospitalization rate was not statistically significant. Nonetheless, Genesis Healthcare recognized improvements in quality of resident care and, subsequently, the eINTERACT evaluation tool has been implemented as the standard documentation process for its nursing staff nationwide.

HIT Use

While Fischer’s exact chi square models reported post-implementation improvement in nurse perception of communication with providers (Fischer X2=29.40, P=<.0001), some nurses continued to face barriers incorporating SBAR and HIT into daily use. According to demographic information, nursing staff had an average 10 to 15 years’ experience (standard deviation [SD] 1.4 ) working with older adults. Further research may explore the roles of clinical expertise with technological advancements within a familiar work environment. Are seasoned nurses interested in learning new software, or are they satisfied with traditional practices? Additionally, registered nurses (n=32, 56.1%) who held associate degrees (n=30, 52.6%) were leading project participants. Further research is needed to determine if degree and license level influence clinical decision support tool utilization and communication with medical providers.4

Provider-to-Nurse Communication

Fischer’s exact chi square models did not show significant results between the pre-implementation Likert scale responses compared with post-implementation responses, most likely due to the small sample size of providers. Due to the convenience sample used in this quality improvement project, a limited number of providers was available to participate, which impacted outcome strength. Despite this challenge, results showed similar outcomes as the Renz et al study, which demonstrated provider communication with nurses impacted decisions about resident transfers.4

Center A Rehospitalization Increase

Despite encouraging outcomes regarding the ability of eINTERACT to improve staff communication, Center A demonstrated increased rehospitalization rates upon completion of the project. Throughout implementation, Center A experienced challenges caring for an end-stage ventilator population. Because many of these residents desired full scope of treatment, early identification of ailments resulted in frequent hospitalizations.

As resident and family choice is a major factor in the decision to transfer to the hospital, open and frequent communication among providers, residents, and family is a key factor in reducing rehospitalizations.4 Further recommendations include discussion with a nurse practitioner about advanced care planning and palliative treatment options. By focusing on the comfort and quality of life, facilities may see improved resident satisfaction and reductions in costs associated with redundant hospitalizations.

Limitations

This quality improvement project examined two facilities within a single geographic location, which limits its generalizability. Though the raw results could be representative of a sizable population, analytical tests and descriptions were given at a two-location (two-subjects) level, resulting in limited power for the statistical test. Further research should include a wider selection of SAR facilities, including those that may have already adopted HIT into everyday practice, to confirm findings.

To examine the trends of leading rehospitalization diagnoses, including heart failure, septicemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cerebral vascular accident, this quality improvement project could be tested in defined patient populations.8

Conclusion

While this study yielded statistically mixed results, the success of this quality improvement project prompted the introduction of HIT advancements into SAR facilities across the United States. Through continued advocacy for policy changes, additional SAR centers could expand the meaningful use of HIT within more facilities.

References

1. Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Tappen R, et al. Interventions to reduce hospitalizations from nursing homes: evaluation of the INTERACT II collaborative quality improvement project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):745-753.

2. Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Perloe M, et al. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations of nursing home residents: frequency, causes, and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):627-635.

3. Carnahan JL, Unroe KT, Torke AM. Hospital readmission penalties: coming soon to a nursing home near you! J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(3):614-618.

4. Renz SM, Boltz MP, Wagner LM, Capezuti EA, Lawrence TE. Examining the feasibility and utility of an SBAR protocol in long-term care. Geriatr Nurs. 2013;34(4):295-301.

5. Handler SM, Sharkey SS, Hudak S, Ouslander JG. Incorporating INTERACT II clinical decision support tools into nursing home health information technology. Ann Longterm Care. 2011;19(11):23-26.

6. PointClickCare. https://www.pointclickcare.com/senior-care-industry-specific-software-solutions/assisted-living-facilities/. Accessed April 11, 2019.

7. Genesis Healthcare. Our services. https://www.genesishcc.com/our-services/our-services-overview. Accessed April 11, 2019.

8. Ouslander JG, Diaz S, Hain D, Tappen R. Frequency and diagnoses associated with 7- and 30-day readmission of skilled nursing facility patients to a nonteaching community hospital. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(3):195-203.