Effective Antibiotic Stewardship Programs at Long-Term Care Facilities: A Silver Lining in the Post-Antibiotic Era

Affiliations: 1Division of Infectious Diseases, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI 2Director, Infection Prevention, Epidemiology, and Antibiotic Stewardship, Kindred Hospital and University Health Center, Detroit, MI 3Department of Family Medicine and Public Health Sciences, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI

Abstract: The number of Medicare patients aged 65 years and older is increasing at an unprecedented rate. This population faces a number of healthcare challenges, including infections caused by multidrug-resistant organisms. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Clostridium difficile, for instance, are two bacterial strains that pose an urgent threat to elderly individuals, especially those residing in long-term care facilities. A solution to these problems may lie in effective antibiotic stewardship programs. Use of an interdisciplinary staff and infection control measures may help curb these threats to residents of long-term care facilities.

Key words: Antibiotic stewardship program, quality of life, Clostridium difficile, infectious disease, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae.

Healthcare is a constantly evolving field with new developments occurring at a rapid rate. Some of the most important developments in the field are related to the laws of healthcare. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), for instance, which was signed into law in 2010, places an emphasis on long-term patient outcomes, the creation of Accountable Care Organizations, and integrated health models that focus on treating mental and behavioral health as well as conventional physical health.1 The PPACA aims to create positive, long-term health outcomes for patients by treating both of these facets of human health, rather than simply treating the intermittent, short-term symptoms of different diseases.1 Accountable Care Organizations are voluntary groups of healthcare providers that coordinate care for all Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, especially chronically ill patients, to ensure proper and timely delivery of healthcare. This reorganization of healthcare laws, clinical practice, and medical treatment will greatly affect those who rely on Medicare as a primary way to pay for medical bills.1

According to recent data, at least 84% of Medicare beneficiaries are aged 65 years and older.2 This is an age bracket that is rapidly increasing in number due to the aging of the baby boomer population, who started turning 65 in 2011.3 In 2050, the population aged 65 years and older is projected to be 83.7 million, almost double its estimated population of 43.1 million in 2012.4 Many of these patients will receive medical care at long-term care (LTC) facilities, such as nursing homes, skilled nursing facilities, and long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs). Because the residents of these facilities are typically older and have more chronic illnesses, they have an increased susceptibility to developing various infections, and therefore will require more attention from healthcare providers, institutional resources, and monetary support from private and governmental sources. These patients are often required to be transferred to other facilities at an increased rate to ensure that the most appropriate care is being provided. The need for extra care, in conjunction with the requirement to coordinate care due to Accountable Care Organizations, will create opportunities for these patients to be exposed to new environments and new pathogens.

The Problem of Antibiotic Resistance

Many kinds of bacteria are beginning to develop a resistance to the antibiotics that are currently being prescribed by healthcare providers on all levels, including nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and physicians. The emergence of resistant bacteria put not only LTC residents at risk, but also the community at large. Colonization with multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) coupled with antibiotic misuse (eg, inappropriate prescribing) at LTC facilities contribute to a vicious cycle in which antibiotic resistance spreads quickly in the community and in LTC settings.

A 2012 study of 13 different hospital facilities in southeastern Michigan found that a prior stay in an LTC facility put patients at an increased risk for infection by an MDRO.5 Individuals who were directly admitted from an LTACH had an odds ratio (OR) of 4.31 for infection by a multidrug-resistant gram-negative organism than a multidrug-resistant gram-positive organism.5 Patients also had an elevated risk (OR, 4.75) of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) infection as compared with patients with other MDROs.5 Also, being age 60 years or older was associated with direct admission from an LTACH.

Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported CRE and Clostridium difficile as urgent threats to public health.6,7 CREs are of particular concern to LTC residents. A 2013 point prevalence study conducted in short-stay acute care hospitals and LTACHs in Chicago showed that 30.4% of patients in LTACHs were colonized with CRE, while only 3.3% of patients in short-stay acute care hospitals tested positive for colonization.8 Further, LTACH patients experienced a 9.2 prevalence ratio for Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase–producing Enterobacteriaceae compared with patients not in an LTACH.8 A similar study conducted in Los Angeles County found that incidence rates of CRE were nearly 8-fold higher for patients who were residing and receiving care in LTACHs compared with those of patients who were in short-stay acute care hospitals.9

In a 2012 study of patients admitted to four different hospitals in the Chicago area, it was found that 8.3% of those who were transferred from LTC facilities were colonized with CRE and that none of the patients admitted from the community were colonized with this resistant strain.10 In the same study, risk factors identified for colonization with CRE included being a patient at an LTACH, use of mechanical ventilation, and prolonged length of stay. These factors should be of great concern when caring for the aging population, as these individuals frequently reside in LTC facilities, require assistance from respirators, and remain in LTC settings for extended periods of time. Another study found that patients who had previous culture-confirmed exposure to CRE and those with a documented history of exposure to CRE experienced an increased burden of skin colonization compared with those who did not have a previously documented exposure or a positive culture.11 As these patients are frequently transferred from facility to facility, they are at higher risk of infection by CRE.

Another consequence of poor antibiotic prescribing practices is C difficile infection. Although it is not an MDRO, C difficile has become a major threat to the community.6 The following are three potential pathways that may lead to C difficile infection: (1) overprescribing of antibiotics by a healthcare provider; (2) improper cleaning of the surrounding environment; and (3) infection via healthcare worker transfer.12 The reason that this bacterium is of concern is because the overuse of antibiotics can wipe out competing bacteria in the normal flora, resulting in an opportunistic infection of the patient with C difficile infection.13 Traditionally, C difficile infection was easily treated with metronidazole, but this bacterial infection has become much more difficult to treat due to the development of a resistant C difficile strain.13 This development, along with the overuse of antibiotics and improper observation of isolation precautions, has resulted in a steady increase in C difficile infections from 2001 through 2010.13 In fact, a 2013 study found that there was a 47% increase of C difficile colitis cases from 2006 through 2010.13 In this study, one of the major predictors of mortality after C difficile infection and colectomy treatment was age greater than 60 years; and these patients experienced a 1.97-fold increased risk of death after colectomy treatment. Of the patients who survived the colectomy, 51.3% were discharged to a skilled nursing facility.13 This places many LTC residents at an elevated risk of severe complications due to C difficile infection. Because patients in LTC facilities are at a higher risk for infections, either due to age, medical procedures, or both, C difficile infection poses a major threat to this population.

Antibiotic Stewardship Programs

The problem of MDROs and C difficile infection coupled with poor or no antibiotic stewardship programs at LTC facilities create multiple barriers to providing the quality care that these patients deserve. All healthcare settings should either establish an antimicrobial stewardship program or become much more attentive to their preexisting program so that clinicians can maintain—and hopefully decrease—the number of drug-resistant organisms. These programs offer guidelines and safety checks that ensure the proper distribution, administration, and monitoring of the use of antimicrobial treatments.14

An ideal antimicrobial stewardship program would consist of an infectious disease physician, an infectious disease pharmacist, and a microbiologist. These three healthcare providers would ideally interact with one another on a regular basis and disseminate information regarding the status of bacterial colonization and infections, as well as data regarding antibiotic use. The microbiology laboratory would be responsible for regular surveillance of microbes present in the facility. Any positive results would then be communicated to the infectious disease physician, who would prescribe a proper course of antibiotics to treat the infection. Finally, the infectious disease pharmacist would monitor the treatments prescribed by the physician and would communicate any changes to the prescription that may be necessary for patient safety and compliance with antimicrobial stewardship protocols.14

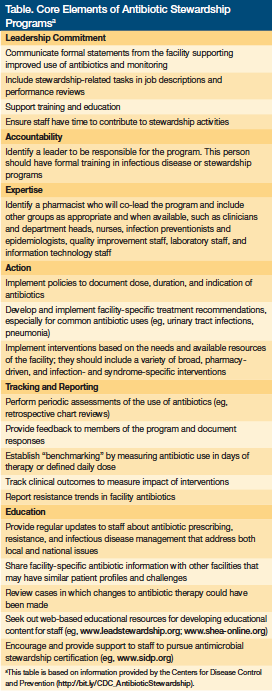

The CDC has a list of core elements for antibiotic stewardship programs on its website at https://bit.ly/CDC_AntibioticStewardship. The elements are recommended based on existing guidelines from organizations such as the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, American Society of Health System Pharmacists, and The Joint Commission. Although these elements are recommended based on their success in hospitals, LTC facilities can take note from them when building their own. The elements are as follows: leadership, accountability, drug expertise, action, tracking/monitoring, reporting, and education (Table). To provide quality care to LTC residents, facilities stand the best chance of implementing models successfully if they follow such guidelines and learn from other successful programs and plans already in place.

An antibiotic stewardship program can be considered a success when it is accepted and implemented by all levels of clinical staff at a given facility. In a study of clinicians’ attitudes toward an antimicrobial stewardship program at a tertiary care children’s hospital, a balance between successful planning, implementation, and clinician adherence was observed with the use of the program.15 Clinicians who participated in this study agreed that by following the guidelines of their antimicrobial stewardship program, there was a decrease in inappropriate use of antibiotics (84%) and improved patient care quality (82%). Further, 91% of participants felt that the program provided knowledge and education about appropriate antibiotic use. What may arguably be the most important finding of this study is that the clinicians at this pediatric hospital did not see the antimicrobial stewardship program as a threat to their clinical decision-making; only 6% of clinicians who participated in this survey felt that the program “interfered with clinical decision-making” and only 5% of the clinicians felt “threatened” by the planning and implementation of this program.15

Cost

Antimicrobial stewardship programs can also be viewed as a financial success for a given healthcare facility. There are very few studies conducted on cost of antibiotic stewardship programs specifically within LTC facilities, but there are several recent hospital-based studies that show the potential of these programs to yield substantial savings. In a 2009 cost-effectiveness analysis performed on antimicrobial stewardship evaluations of patients with blood stream infections, it was determined that an evaluation of a patient’s case would save a healthcare facility money in the long run.16 The initial implementation of the program would be a cost for the facility, but in this particular analysis, it was determined that the hospital would experience a cost of $2367 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), which is less than costs of other healthcare issues, such as myocardial infarction, which has a cost of $4500 per QALY.

To calculate actual sustained savings over time, a retrospective study was conducted on the administration of antibiotics over a 6-year period at the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center.17 This study followed the tertiary care pediatric hospital’s upgrading of its antimicrobial stewardship program to an online preapproval program on July 1, 2005. After analyzing the cost savings of the implementation of this upgraded antimicrobial stewardship program, it was determined that the preapproval antibiotic stewardship program saved $103,787 (95% confidence interval [CI], $98,583-$109,172) per year, or $14,156 (95% CI, $13,446-$14,890) per 1000 patient-days.17 Because of the lack of information available in the literature it would be advantageous to complete a cost-effectiveness study or cost/benefit analysis of antimicrobial stewardship programs in an LTC facility.

Effectiveness

Implementation of an effective antimicrobial stewardship program can have a positive effect on decreasing the use of antibiotics and the length of therapy for patients.18 For example, a pharmacist-led study conducted in an LTC facility resulted in a reduction of inappropriately prescribed antibiotics by nearly 50%.19 This study was two-fold, with one part being observational in nature and the second part being interventional. In the first part of the study, pharmacists collected and analyzed data relating to prescribing of antibiotics; prescriptions were classified as either appropriate or inappropriate based on criteria relating to current antibiotic guidelines, patient health status, and culture/sensitivity reports. It was found that 40% of the antibiotics were prescribed inappropriately per the study criteria. During the interventional stage, pharmacists made recommendations to providers if the criteria were not met in order to stem inappropriate antibiotic prescription. During the 3-month period after implementation of the antimicrobial stewardship program, it was found that inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics dropped from 40% to 21%. Although this study was limited in terms of number of patients (n=29), required onsite pharmacy staff, and resulted in only 12 interventions, it demonstrated that antimicrobial stewardship programs can be of great use to LTC facilities.19

Another study conducted in an LTC facility associated with a Veteran’s Affairs hospital showed that implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship program was successful in reducing the number of antibiotic prescriptions overall, as well as decreasing the trend for patients who test positive for C difficile.20 This study compared 36 months of antimicrobial data from the site before an antimicrobial consultation service was introduced, to data collected from the same site 18 months after the consultation team was introduced. When comparing the data, the team found that systemic antibiotic administration was decreased by 30% (P<.001), oral antibiotic use decreased 32% (P<.001) and intravenous antibiotics decreased by 25% (P=.008). Reduction of overall prescriptions reduces the chances of unnecessary prescriptions as well as reducing the risk of developing resistant strains of already dangerous bacteria. Aside from reducing the total number of prescriptions, the antimicrobial stewardship program changed the trend in the rate of positive C difficile tests. Before the implementation of the program the rate of positive C difficile tests was increasing (P=.09) while after the program commenced there was a reversal in the trend resulting in a decreasing trend (P=.21).

The effectiveness of antimicrobial stewardship programs is not exclusive to LTC facilities, however. In a quasi-experimental design performed by analyzing pre- and post-antimicrobial stewardship program data from the Sanford Medical Center Fargo, it was determined that the program was a success.21

Antimicrobial expenditures were steadily increasing in the years preceding program implementation by an average of 14.4% per year. Researchers reported a 9.75% cost decrease in the program’s first year that remained relatively stable in subsequent years. The overall savings were approximately $1.7 million over a 3.5-year period (April 2007-December 2010). The patients benefited from the program as well, with decreases in MDRO infections from bacteria such as C difficile, Staphyloccocus aureus, and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci.21

Important Considerations

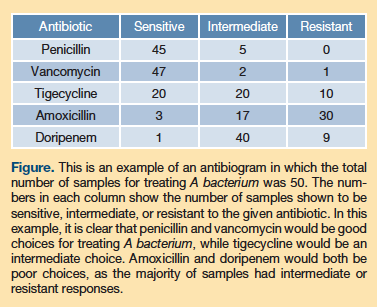

When considering the implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship program, it would be important for healthcare facilities, particularly LTC facilities, to have a clear picture of the susceptibility pattern of the various kinds of bacteria they are dealing with. A tool that has proven useful in providing this picture to healthcare facilities is the antibiogram (Figure).22 An antibiogram is a summary report that is meant to guide the clinician in prescribing antimicrobials, particularly antibiotics. These reports include a description of how susceptible to treatment the bacterial strains in a certain facility are, and a general idea of what strains are of concern to providers.23

In a 2012 comparison study of antibiograms (one from an LTC facility and one from the hospital associated with the LTC facility), researchers found that the antibiogram of the LTC facility had higher antibiotic resistance in both gram-negative and gram-positive organisms.24 These resistant strains were identified in areas such as the ventilation units in the LTC facility, and they are cited as a reason for increasing the stringency of antimicrobial protocols. The results of the antibiogram also suggested that the LTC facility may have had an extended-spectrum beta-lactamase problem that often involved organisms such as Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase, which has been shown to be a problem in LTC facilities.24

To correct the problem of increased resistance in LTC facilities, it is pertinent to train clinicians in how to use an antibiogram and how it can help guide their prescribing of antibiotics. An antibiogram specific to each individual healthcare facility should be developed and updated every 6 to 12 months, and the staff of the facility must also be educated in the proper interpretation and use of that antibiogram. This can be done in collaboration with the microbiology director, who should be made a crucial member of the antibiotic stewardship committee meeting. By performing an annual antibiogram, healthcare staff will become more aware of the bacterial challenges they may face during the upcoming year, and may gain a clearer picture of the types of treatments they should offer to their patients.

Lastly, a successful antimicrobial stewardship program requires a strong infection control program. The administration should encourage the staff to partake in regular handwashing and sanitizing, as well as proper cleansing of care environments, such as those recommended by the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee.25

Barriers

There are a few major barriers to instituting successful antimicrobial stewardship programs in LTC facilities. One such barrier is the lack of a microbiology laboratory on the site of an LTC facility, which can result in a delay of specimen processing and reporting results to healthcare providers. If every LTC facility had an on-site microbiology laboratory, there would be a much faster turnaround time for diagnosis and proper response to recognition of the MDRO. Precaution could be taken to isolate the patient in a much faster window, decreasing the chances of the patient or healthcare workers spreading the organism to other patients. Although it would be ideal for each LTC facility to have its own microbiology laboratory, it is not logical or practical. An establishment of multiple centralized laboratories would be a possible solution for this, as long as the turnaround times remain as fast as possible. This centralization of clinical laboratories was implemented in Alberta, Canada, and proved to be even more successful than originally planned.26

Another major barrier is the improper use of nurses in these programs. Nurses are often the individuals who are in direct contact with patients, and they even serve as an intermediate between physicians and pharmacists and many other healthcare providers.27 These healthcare workers are also essential in carrying out the patient care plans established by upper-level healthcare providers, including the administration of medications, which often include antibiotics.27 To fully optimize nurses as effective healthcare workers in LTC settings and other healthcare settings, a team of nurses should be educated in the infectious disease control aspects of healthcare, particularly control of antibiotics and antimicrobials in general. In a survey of healthcare workers, including physician assistants, nurse practitioners, nurses, and infection control professionals, 63% did not have sufficient knowledge regarding the proper initiation of C difficile infection isolation measures.28

Although MDROs are clearly a problem in LTC facilities, studies have shown that healthcare workers are often unaware of some important aspects of antimicrobial stewardship programs and care for patients with MDROs. In a recent survey of healthcare workers in an LTC facility in Detroit, MI, 47% of individuals reported that they were not sure if their facilities had an established antimicrobial stewardship program. Further, 50% of healthcare workers did not recognize that restricting the use of antibiotics is an effective measure to reduce C difficile infection. Although 92% of respondents reported that they were familiar with what an MDRO is, only 36% of the respondents felt confident in caring for a patient with said organism.28 In terms of specific organisms, 92% were familiar with vancomycin-resistant Enterococci, but only 36% were comfortable in caring for a patient with this bacterium. This trend was also seen for ESBL-producing organisms and CRE; 84% of healthcare workers were familiar with the ESBL organism, while only 36% felt comfortable providing treatment to a patient with this organism. Even fewer individuals were familiar with CRE at 80%, with only 28% feeling comfortable providing care.29

Conclusion

LTC residents have an increased susceptibility to developing various infections, and are frequently exposed to new environments and new pathogens. CRE and C difficile are considered to be urgent threats to public health. Staff, especially nurses, need to be trained in the infectious disease field so that they can provide proper care to patients, notify physicians of potential complications, and keep proper track of the administration of antibiotics. All healthcare settings should have an antimicrobial stewardship program to ensure the proper distribution, administration, and monitoring of the use of antimicrobial treatments. For these programs to become a mainstay in the healthcare industry, it must become a part of the daily culture in all healthcare settings. Facilities need to become more devoted to the idea of prevention by performing an antibiogram and developing an on-campus microbiology laboratory. By creating a system of checks and balances between the microbiology laboratory, infectious disease pharmacists, and physicians, the entire healthcare team can contribute to the antimicrobial stewardship campaign and make LTC facilities a safer place for residents and the community at large.

References

1. Hacker K, Walker DK. Achieving population health in accountable care organizations. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(7):1163-1167.

2. Medicare beneficiary demographics. In: A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; June 2014. Accessed January 19, 2015.

3. Etzioni, DA, Liu JH, Ko, CY. The aging population and its impact on the surgery workforce. Ann Surg. 2003;238(2):170-177.

4. Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: the older population in the United States: population estimates and projections. US Census Bureau. www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf. Published May 2014. Accessed January 19, 2015.

5. Marchaim D, Chopra T, Bogan C, et al. The burden of multidrug-resistant organisms on tertiary hospitals posed by patients with recent stays in long-term acute care facilities. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40(8):760-765.

6. Healthcare-associated infections: Clostridium difficile infection. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/cdiff/cdiff_infect.html. Updated March 1, 2013. Accessed January

7. Healthcare-associated infections: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in healthcare settings. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. www.cdc.gov/HAI/organisms/cre/index.html. Updated June 3, 2014. Accessed January 19, 2015.

8. Lin MY, Lyles-Banks RD, Lolans K, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epicenters Program. The importance of long-term acute care hospitals in the regional epidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(9):1246-1252.

9. Marquez P, Terashita D, Dassey D, Mascola L. Population-based incidence of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae along the continuum of care, Los Angeles County. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(2):144-150.

10. Prabaker K, Lin MY, McNally M, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epicenters Program. Transfer from high-acuity long-term care facilities is associated with carriage of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: a multihospital study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(12):1193-1199.

11. Thurlow C, Prabaker K, Lin M, Lolans K, Weinstein R, Hayden M; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epicenters Program. Anatomic sites of patient colonization and environmental contamination with Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase–producing Enterobacteriaceae at long-term acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(1):56-61.

12. Using drug stewardship to reduce C. diff. Hospital Infection Control & Prevention. 2013;40(3):31-33.

13. Halabi WJ, Nguyen VQ, Carmichael JC, Pigazzi A, Stamos MJ, Mills S. Clostridium difficile colitis in the United States: a decade of trends, outcomes, risk factors for colectomy, and mortality after colectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(5):802-812.

14. Leuthner KD, Doern GV. Antimicrobial stewardship programs. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(12):3916-3920.

15. Stach LM, Hedican EB, Herigon JC, Jackson MA, Newland JG. Clinicians’ attitudes towards an antimicrobial stewardship program at a children’s hospital. J Ped Infect Dis. 2012;1(3):190-197.

16. Scheetz MH, Bolon MK, Postelnick M, Noskin GA, Lee TA. Cost-effectiveness analysis of an antimicrobial stewardship team on bloodstream infections: a probabilistic analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63(4):816-825.

17. Sick AC, Lehmann CU, Tamma PD, Lee CK, Agwu AL. Sustained savings from a longitudinal cost analysis of an internet-based preapproval antimicrobial stewardship program. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(6):573-580.

18. Newland JG, Stach LM, De Lurgio SA, et al. Impact of a prospective-audit-with-feedback antimicrobial stewardship program at a children’s hospital. J Ped Infect Dis. 2012;1(3):179-186.

19. Gugkaeva Z, Franson M. Pharmacist-led model of antibiotic stewardship in a long-term care facility. Annals of Long-Term Care. 2012;20(10):22-26.

20. Jump RLP, Olds DM, Seifi N, et al. Effective antimicrobial stewardship in a long-term care facility through an infectious disease consultation service: keeping a LID on antibiotic use. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(12):1185-1192.

21. Nowak MA, Nelson RE, Breidenbach JL, Thompson PA, Carson PJ. Clinical and economic outcomes of a prospective antimicrobial stewardship program. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69(17):1500-1508.

22. Khattak M, Ishaq M, Gul M, et al. Isolation and identification of pseudomonas aeruginosa from ear samples and its antibiogram analysis. KJMS. 2013;6(2):234-236.

23. McGregor JC, Bearden DT, Townes JM, et al. Comparison of antibiograms developed for inpatients and primary care outpatients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;76(1):73-79.

24. Kindschuh W, Russo D, Kariolis I, Wehbeh W, Urban C. Comparison of a hospital-wide antibiogram with that of an associated long-term care facility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):798-800.

25. Guideline for disinfection and sterilization in healthcare facilities, 2008. CDC website. www.cdc.gov/hicpac/Disinfection_Sterilization/toc.html. Updated December 29, 2009. Accessed January 22, 2015.

26. Church DL, Hall P. Centralization of a regional clinical microbiology service: the Calgary experience. Can J Infect Dis. 1999;10(6):393-402.

27. Ladenheim D, Rosembert D, Hallam C, Micallef C. Antimicrobial stewardship: the role of the nurse. Nurs Stand. 2013;28(6):46-49.

28. Awali R, Sadasivan S, Patel P, Marwaha B, Biedron C, Samuel P, Chopra T. Health care workers at long-term care facilities - how much do they know about Clostridium difficile infection? Paper presented at: ID Week 2013; San Francisco, CA. Abstract 1413.

29. Biedron C, Awali RA, Mudumuna S, Jegede O, Samuel P, Chopra T. No healthcare facility is an island – an assessment of healthcare workers’ knowledge of infection prevention and antimicrobial resistance in a long-term acute care facility. Paper presented at: Michigan Chapter Annual Scientific Meeting 2013; Bellaire, MI.

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial information.

Address correspondence to: Christopher Rivard, MPH, Wayne State University, University Health Center 4201, Saint Antoine Street, Suite 2B, Detroit, MI 48201; rivardchris1@gmail.com