Difficult Resident or Personality Disorder? A Long-Term Care Perspective

Most healthcare providers have used the term difficult patient and are convinced they know what it means, yet it is a term that defies exact definition. When a resident in a long-term care (LTC) setting exhibits behaviors that are rude or socially inappropriate, for example, providers may feel strong emotions that interfere with their work satisfaction and with the care of the resident. Such behaviors can increase tension throughout the LTC system as providers attempt to cope with the situation. Many residents who are labeled difficult, however, may have long-standing personality disorders that are amenable to some level of improvement if appropriate interventions are implemented. The authors examine the practical concerns encountered in the care management of these residents, detail how to ascertain whether a personality disorder is behind problematic behaviors, and offer ways to better cope with these individuals, including by using the ABC model, a behavioral management tool.

Key words: Personality disorders, long-term care, difficult patients, behavior management, mental illness, ABC model.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

A search for the term difficult patients in the literature yields a myriad of definitions, classifications, characteristics, and staff coping strategies. Examples of difficult patients often include patients who threaten lawsuits, don’t listen to reason, constantly and reflexively challenge recommendations, do not adhere to treatment regimens, demonstrate manipulative behaviors, and make inordinate demands. The inability of caregivers to please and adequately treat these patients can wear providers down and have a negative impact within long-term care (LTC) facilities. Yet little has been written on the subject of the difficult patient in the LTC setting. What can be found is often based on personal experiences contained in online discussion boards, on Websites, or via a few posted presentations on the subject. Yet professionals in LTC facilities know that residents with difficult behaviors can take up an inordinate amount of physician and nursing time and energy. The term difficult patient, however, is a catchall phrase, and when patients exhibit certain troublesome behaviors, it may be more useful to determine whether a personality disorder is present, as interventions can then be employed that might curtail these behaviors.

We describe how to identify residents with personality disorders and strategies and tools for managing difficult behaviors. We also outline the kinds of support and education caregivers need to implement these strategies and discuss how to develop an effective care plan that preserves the patient’s dignity and the caregiver’s professionalism. An illustrative case is provided to help show how some key behavioral management approaches can be put into practice in the LTC setting.

Difficult Behavior

First, let’s examine some types of difficult behaviors in more detail. A classic paper by Groves proposes that difficult patients can be classified by a combination of observed behaviors as well as by the powerful emotional responses that those behaviors evoke in healthcare providers.1 Groves explains, for example, that clingers evoke aversion when they break through the caregiver’s emotional boundaries and try to get too close, demanders evoke a wish to counterattack, help-rejecters evoke depression as the clinician begins to share their pessimism, and self-destructive deniers evoke feelings of malice.1 Psychologists and psychiatrists call these feelings in staff members countertransference and projective identification,2 terms that will be discussed later in this article in the “Using Staff Reactions to Help Confirm a Diagnosis” section.

Some patients classified as difficult may have medical problems, such as dementia or cognitive impairment as a result of subcortical or frontal lobe abnormalities from alcohol use, mental illness, drug abuse, age-related changes, or head injury. Such issues can be identified by using cognitive assessment tools, including the Mini-Mental State Examination or the Brief Interview for Mental Status.3-5 Other residents with difficult behaviors may have Axis I mental illnesses, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).6 This may include psychosis, depression, or bipolar disorder. In other patients, several disorders may coexist; for example, dementia, substance abuse, and a mental disorder.

In addition, difficult behaviors may be related to a combination of these factors or may be a manifestation of a personality disorder. Therefore, it is important to identify which factors are contributors so that appropriate therapeutic strategies can be developed.

Personality Disorders

The DSM-IV defines personality disorders as Axis II disorders, which have “an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectation of the individual’s culture…and this enduring pattern is inflexible and pervasive…[leading] to clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.”6 Personality disorders are further classified into clusters: A, B, C, and NOS (not otherwise specified). Cluster A includes odd or eccentric behaviors. Cluster B comprises antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders and is thought to be the most challenging to treat. The clinical presentation of these patients is typically dramatic, emotional, or erratic, and evokes strong reactions in the patient and in others. Cluster C includes traits of anxiety and fearfulness. The NOS category is used when traits are severe but do not fit any specific DSM-IV syndrome and the behavior traits overlap several categories.

The prevalence of personality disorders among US adults is estimated to range between 9% and 14.8%.7,8 More adults may have traits of a personality disorder, but never receive a formal diagnosis. These persons may be able to maintain adequate function and/or avoid interaction with mental health practitioners. Personality disorder symptoms may also overlap with other disorders of mood, such as depression or anxiety, or coexist with a history of substance abuse; however, for a diagnosis of personality disorder to be made, the characteristics of the disorder must persist even in the absence of substance abuse or mental illness exacerbation.

Although individuals with a personality disorder can be troublesome in medical offices and in psychiatric facilities, management problems can be magnified in LTC settings. Behaviors that occur at home can be hidden from an office physician, but very little can be hidden in an LTC setting, and clinicians have less ability to terminate provider or facility relationships. LTC residents live with their healthcare workers for lengthy periods and have more ready access to staff than are accessible to outpatients or to patients in short-term psychiatric facilities. The combination of illness and cognitive decline in residents with personality disorders can increase anxiety levels and lessen the ability of these residents to regulate their emotions further. Because residents are removed from the context of their previous living arrangements and family support, clinical staff can often clearly see the extent of the person’s eccentricities.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of personality disorder in an LTC resident starts with observations of the resident’s behavior and the impact that those behaviors have on the feelings and reactions evoked in the staff members and their effects on the system as a whole. Consultation with a psychologist, psychiatrist, or other mental health professional is the simplest way to reach a diagnosis. If these professionals are not available as resources, a nonpsychiatric physician can use the DSM-IV criteria to aid in making the diagnosis. Because personality disorders reflect enduring patterns, assessment involves sustained observations or reliable information regarding behavioral history from the individual or from others who know the resident well. Individuals with personality disorders have generally had longstanding problems with interpersonal relationships, including avoidance, fear, chaos, instability, and abuse.

Reviewing the DSM-IV criteria for personality disorders before the resident is interviewed will help clinicians obtain the information needed to make a more specific diagnosis. For example, the initial impression may be that the resident has a personality disorder in the NOS category, but on sustained observation, a more specific diagnosis might be developed.

(Continued on next page)Using Staff Reactions to Help Confirm a Diagnosis. People with personality disorders unconsciously affect the feelings, moods, and actions of others.2 Although LTC providers may experience feelings of being out of control, manipulated, inadequate, frustrated, irritated, angry, fearful, or all of these emotions at various times, these feelings are typically transient. When the reaction experienced is consistent, strong, or uncharacteristic, and is related to the care of a particular resident, that resident may have a personality disorder that is evoking the emotion. In such cases, transference, countertransference, and projective identification may occcur.2

Transference is an unconscious process in which a resident reacts to his or her caregiver based on the resident’s past relationships and experiences, rather than on what is happening in the present. Countertransference is the clinician’s emotional response to his or her patient, often due to patient traits that remind the clinician of personal situations. Projective identification refers to the process where the individual with a personality disorder takes his or her chaotic, emotional, dramatic, and sometimes abusive internal world and projects these elements onto others with such effect that these persons begin reacting to the projected material.2 For example, a mild-mannered clinician speaking to a battered woman might be shocked at his or her own feelings of aggression toward the perpetrator. Alternatively, a clinician may note a strong feeling of wanting to either punish or protect a patient. Projective identification may be uncomfortable and may evoke feelings of the loss of one’s self or of being ungrounded.

Similar to Groves’s taxonomy referred to earlier, Kernberg2,9 defines certain traits as provoking typical reactions in caregivers. For example, Kernberg notes that the dependent personality may evoke anger and the desire to have these persons take responsibility for themselves; narcissistic personality can make caregivers feel uncertain or stupid; individuals who act entitled (common with narcissistic and antisocial personality disorders) may evoke avoidance; and demanding individuals may lead caregivers to try harder to satisfy and please them, but to no avail. Clinicians should be on the lookout for traits of borderline personality disorder if some staff members express feeling that they are somehow special and exceptionally gifted in working with a difficult individual, and if others would only act more like they do, that this would solve any problems the other staff members are experiencing. Although patients with a borderline personality disorder may sometimes appear pleased, they will quickly become unhappy if their behavior is thwarted. Although borderline personality disorder is ultimately an extreme exaggeration of personality traits that persons without personality disorders may at times exhibit, these individuals, like other persons with personality disorders, exhibit profound splitting (seeing others as “all good” or “all bad”), leading to instability in interpersonal relationships, unstable self image, and often self-destructive impulsivity.7 Clinicians should also consider the presence of a personality disorder when they or other staff members express vague feelings of evil or of having been manipulated, as antisocial traits can evoke such feelings. In addition, antisocial people typically cannot sustain a connection with anyone, including caregivers, and they cannot see the perspective of another person or feel empathy.2,7,9

Treatment

Personality disorders are notoriously challenging to treat and the problems of doing so may be compounded in the LTC setting because of a lack of resources, cognitive loss in the resident, poor reimbursement for therapy, and lack of motivation by caregivers or facilities. The following sections discuss what is and what is not useful in the treatment of patients with personality disorders in the LTC setting.

Psychotherapy. Because the etiologies of various personality disorders are thought to be developmental in nature and the product of a combination of genetic, environmental, and relationship elements that usually manifest in adolescence or early adulthood, the negative patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving have become deeply entrenched; thus, improvement may take years of weekly therapy, a time-frame that simply may not be feasible given the life expectancy of many nursing home residents. For example, proponents of various treatment approaches generally agree that 1 to 1.5 years is the timeframe needed to address critical issues, such as suicidal behavior or self-mutilation in persons with borderline personality disorder, and that therapy may need to continue for 5 to 10 years if other issues also need to be addressed, such as maintaining healthy personal relationships.10

Another issue with psychotherapy as a treatment option in LTC is that this treatment requires that the patient recognizes the need to engage in therapy and is capable of participating in a sustained therapeutic process. This may be a problem for some patients, particularly those with any cognitive impairments. In addition, many LTC facilities do not have ready access to these professionals, and even if consultations can be arranged and are not refused, it is unlikely that a brief consultation or two with the resident will yield significant results regarding the resident’s behavior. Personality disorders are chronic in nature, and residents generally do not arrive at LTC facilities with the psychotherapeutic process as the main priority. Based on admission criteria and demographics, they are more likely to be at a stage in life where medical concerns take precedence, and the stress of their medical situation sometimes intensifies the entrenched, negative coping behaviors that others find so difficult to deal with.

Therefore, although nurses and physicians may have high hopes that referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist will cure a difficult patient of his or her personality disorder, there are just too many obstacles to make this a possibility. Furthermore, few nursing home residents are candidates for the intensive psychotherapy that is required to treat the illness. In our experience, although brief interactions with a psychologist were helpful, few residents were motivated or cognitively able to

tolerate ongoing psychotherapy in the LTC setting.

This does not mean that psychologists or psychiatrists have no role to play in helping LTC staff deal with residents who have personality disorders. These healthcare professionals can be invaluable in shedding light on staff observations of such residents, in helping to set realistic objectives for behavioral management, and in evaluating the appropriateness of pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions. When a personality disorder is identified and the staff is educated on it, the staff is able to see the behavior as a sign of the resident’s illness, rather than a personal attack. Knowledge that the behavior is out of the resident’s direct control provides a buffer from the full impact of the behavior. Staff members usually report that they have a higher tolerance for undesirable behaviors when they identify the behavior as related to an illness, rather than as being directed at them personally.

(Continued on next page)

Medications. Medication may be used as an adjunct to address Axis I conditions, such as mood disorders or transient symptoms of anxiety or psychosis, but they are generally of little benefit in managing a personality disorder.10 We have found that most residents with personality disorders in our facility were taking psychotropic or benzodiazepine agents or pain medications on admission, and in many cases, had done so for years—whether legally or illegally. Residents often saw these medications as necessary to alleviate symptoms of distress and requested dose escalations.

In contrast, the staff viewed the drugs as inefficient in palliating emotional and physical pain and anxiety in patients with a personality disorder, and they sometimes had unacceptable side effects. Some residents had years of drug-seeking behavior exhibited by misreporting symptoms or “doctor shopping” to obtain drugs despite having no medical indications for them. In our experience, medications that affect cognitive and emotional functioning, such as the benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and opioids, can exacerbate the behavioral disturbances seen in people with personality disorders. In the LTC setting, medication dose reductions of these agents combined with nonpharmacological interventions were well tolerated and improved function. Stopping these agents sometimes created initial distress. Within weeks to months, however, noticeable improvements occurred in clinical condition, reduced staff time in monitoring and administering the drugs, and less risk of negative consequences, including addiction, lack of inhibition, and hyperalgesia.

In cases of self-reported pain, we initially increased the pain medication. After dose escalations resulted in repeated reports of “10” on the pain scale, however, and no discernible improvement in quality of life or activity related to the drug occurred, the resident was documented to have opioid-resistant pain. We then reduced or eliminated the pain drug. In most cases, behavior improved, as did resident-assessed indicators of pain, quality of life, and happiness.

Behavioral Management

A well-known behavioral management tool is the ABC model, which stands for antecedent, behavior, and consequences. This tool is based on a learning or behavioral perspective and can be a good first step in effective behavioral management. The antecedent represents the person’s need, the behavior is the result of the person’s effort to have his or her need met, and the consequences are the events that result from the behavior. Targets of intervention may include manipulation of antecedents and consequences to modify behavior. Before we outline each item in the ABC model in greater detail, we provide an illustrative case that will help put this model in context.

Illustrative Case

Mr. A is an articulate resident who seems reasonable at times, but staff regularly report an array of troubling behaviors, such as exposing himself, hoarding linens, and demanding that rubber bands be placed on his arms and legs when getting dressed. Regardless of the quality of care, he remains unsatisfied and constantly threatens to sue and report everyone who does not give him what he wants. He has submitted more than 13 complaints about individual staff members in the past week, and he pushes the call light every few minutes even when staff members are in the room with him.

Despite explanations of proper behavior, Mr. A continues behaving disruptively, which causes tension among staff members and other residents. When caring for him, staff members sometimes doubt their observations about Mr. A’s behavior and continually think about what he had said, defending their actions and trying harder to connect with him. They express feeling anxious and worried that he will complain about or sue them. As a result, they spend an inordinate amount of time trying to write down everything he says, and the resulting shift notes are more than a page long. Staff members often state that they “can’t stand it anymore” and ask, “What can we do?” Yet they do not follow suggestions that are made and continue to complain about his behaviors. No one wants to be assigned to him and he refuses to see a psychiatrist.

As a result, the team gets together to get a second opinion, including from a consultant psychologist, who provides a diagnosis of personality disorder NOS (not otherwise specified7) with paranoid and borderline traits. The entire staff is led to develop a list of practical rules and limits based on the ABC model that would assist in meeting Mr. A’s needs (the antecedents), thus decreasing negative behaviors. All of the resident’s caregivers are expected to read and follow the entire care plan with the goal of reinforcing positive behavior and eliminating as much negative behavior as possible. A brief sample of the rules for the staff and the resident, with sample staff approaches and rationales, is shown in Table 1.

As the care plan develops, each problem behavior and its contributing factors are identified, with specific goals and approaches. For example, Mr. A’s habit of frequently pushing the call light button was identified as potentially stemming from memory loss, fear of abandonment, the need for control and reassurance, a desire to connect with others, or all of these. To address this behavior, he was encouraged to call less frequently, gradually expanding time increments from every few minutes to once or twice in the morning and afternoon. A nursing assistant would meet his underlying needs by visiting him every hour, complimenting him on reducing the call frequency and rewarding that behavior by staying to talk with him for a few minutes.

Antecedents

In 1934 and 1942, Helene Deutsch, an Austrian-American psychoanalyst, described the “as if” personality, which has come to be known as borderline personality disorder.11 Although this is now an outdated term, it sheds light on some of Mr. A’s behaviors. People with this personality disorder manage their interpersonal relationships by becoming what they think the other person wants to see to avoid abandonment, maintain relationships, or achieve some other objective. It explains why the staff thought that sometimes Mr. A made sense, despite general staff reports and experiences to the contrary. He is not consciously manipulating the staff, but he is exhibiting a maladaptive effort to maintain connections with everyone and preserve a sense of control, although he is unable to negotiate the differing demands from various individuals. Mr. A’s desire to maintain relationships while also controlling them are examples of his antecedents, or unmet needs.

To address these needs, the staff established a written care plan with specific limits that gave Mr. A some sense of control and enabled him to hold the staff accountable for that plan. These rules had to be carefully and exactly communicated from shift to shift to ensure consistency. Staff also assured him that he was not going to be discharged (abandoned) from the facility and complimented him on any positive social behaviors, such as noticing another resident in need. Finally, staff were careful to support each other by assuring Mr. A that other caregivers had positive reports of his behavior, which in turn reduced his fear and paranoia. Identifying the antecedents and meeting Mr. A’s unmet needs improved his behaviors.

Behaviors

The next step in the ABC model is to decide what specific behaviors exhibited by the resident are the most disconcerting or troublesome. Although this sounds simple, it is often challenging in the chaotic and emotional atmosphere that can be created by people with personality disorders, and this situation may cloud the thinking of caregivers. Behaviors should be defined objectively by describing the behavior precisely and outlining why and for whom it is a problem.

In Mr. A’s case, the priorities for staff intervention were behaviors that affected others, such as the excessive use of staff time and linens, and manipulating staff to do tasks that were harmful to his health, such as applying rubber bands to his arms and legs “to prevent contaminants from entering through gaps in his clothing.” At a care plan meeting, staff identified the specific list of rules and limits with regard to linens, staff time, scheduling, and staff responsibilities. Identifying specific behaviors enabled the staff to tailor a management plan to deal with them and reduce their incidence. Although nonadherence was part of the negative behavior pattern Mr. A exhibited, this was not categorized as a priority because he had the right of informed refusal, but he also had to accept the negative consequences of that refusal.

(Continued on next page)Consequences

Consequences, or the C component of the ABC model, are the events that occur as a result of a behavior. For example, if the antecedent is the need for reassurance, the behavior may manifest as pushing the call light repetitively, and the consequence is that staff will answer it, thereby reinforcing the behavior. One way to manage behavior in these situations is to change the consequences. In response to excessive calls, for example, staff members could limit verbal interactions to the minimum clinically indicated, but spend some “extra” time with Mr. A on scheduled visits when he does not incessantly press the call button. This minimizes the reward for inappropriate behavior and increases the reward for appropriate behavior, promoting desirable behaviors.

Staff should examine their current strategies to determine what works and what does not. In the case of Mr. A, the nursing assistants’ (NAs) strategy was to tell him that they would report his behavior to the doctor or supervisory nurse. Although the NAs considered this to be limit setting, it was perceived as threatening by Mr. A; thus, his need (the antecedent) was not met and his feelings of paranoia and anxiety increased, which resulted in him complaining more. His efforts to meet his needs included pushing the call light more often, a behavior that enabled him to feel greater control and decreased his anxiety—the consequence. Thus, the staff had inadvertently reinforced Mr. A’s complaining, with no change in consequence for them or for him.

In contrast, when the staff calmly praised positive behaviors, ignored negative ones, and stopped explaining why his behavior was troublesome, Mr. A’s satisfaction improved, altering the antecedent. The staff in turn felt empowered, which further reduced tension in the relationship and changed the consequence for them as well.

Planning for Behavioral Management

Behavioral management plans, such as the ABC model, add structure but take time to develop, require oversight, and should not be used unless they are going to be followed precisely. All behavior management plans should focus on positive reinforcement, rather than on anything that may be perceived as taking away or limiting the resident’s autonomy or interpreted as punishment by the resident and his or her family. In addition, any plans that might violate the rights of the resident must be avoided. A psychologist or physician can assist by translating an analysis of the situation into rules for standard responses that are consistent with LTC practice. The plan must be practical and simple, as it will need to be enforced daily by caregivers, usually the NAs.

To address Mr. A’s antecedents and behaviors and to adjust the consequences, a list of “rules” reflecting physician orders and standards of care was developed; a series of responses to threatening or yelling was written out for staff to follow, and a variety of specific interventions were listed. Table 1 shows some of the rules, interventions, and responses for dealing with yelling, threatening, and other undesirable behaviors. These rules and approaches were the end result of the functional behavioral assessment and analysis of ABC components, which were distilled in the form of clear and basic rules and responses that staff could refer to when needed, especially when tension ran high. As the rules were provided to Mr. A and reinforced, he began to feel more secure, and care consistency improved because both he and the staff knew exactly what could be expected.

Documentation

Documentation can be challenging for staff when caring for residents with personality disorders. There is often much to write, the chaotic atmosphere can be hard to describe, numerous problems are usually identified, planning can be time-consuming, and there is actually less time for all of this as the resident’s demands escalate. In addition, the emotion engendered by the situation can come through in documentation, leading to notes that may sound angry, frustrated, negative, or include subjective interpretations or reactions that may reinforce a negative view of the resident by staff and be seen by surveyors or attorneys as demonstrating malice toward the resident by the staff and the institution.

Documentation is critically important and needs to be done well. The best documentation is done by several team members and describes their observations as well as the effects of the resident’s behaviors. Documentation should use neutral and person-centered language to describe the behavior and the approaches used to alter them. For example, it should identify the resident’s underlying needs, demonstrate empathy for the resident’s lack of abilities to meet those needs, outline goals for helping the resident develop better relationships with staff and peers, and note the strategies that will be used to meet the resident’s needs and the goals set for him or her. We recommend that a staff member with excellent communication skills interview colleagues about their observations and write the summary notes that describe and link the various observations and establish realistic team goals and interventions. A sample summary note for Mr. A appears here:

Review of challenges in the care of Mr. A: The resident was evaluated, the staff caring for him were interviewed, and a care plan was developed. This past week, Mr. A decreased the number of times he pushed the call light, but he developed a new behavior of requesting multiple “blue pads,” which he is stacking on the bed and storing in drawers. He continues to have a low frustration tolerance, manipulates younger or newer staff to violate the established rules, and registers complaints more than four times a shift about all staff assigned to care for him. He continues to struggle with developing relationships with peers, although he was seen in a brief conversation at lunch yesterday. He prefers to engage with staff, but often spends most of that time complaining. Staff were observed reinforcing the resident’s positive behavior by reminding him of his progress and engaging with him before a specific request occurred. The care plan was updated to restrict the resident to one blue pad at a time. Ongoing support and education with clear instructions were provided to all caregivers.

Staff Considerations

Staff assigned to residents with identified personality disorders should be skillful and centered. Several types of caregivers should not be assigned to these patients, including those who try too hard to please, as they cannot maintain consistency in the face of inappropriate resident demands; those who are particularly prone to gossip or to undue reactivity, as they may worsen staff and resident conflict or be prone to reactions that may constitute abuse; and caregivers who are too forceful or paternalistic, as they are not therapeutic. Beneficial qualities include being able to find something to like in these challenging residents; resiliency when criticized, threatened, or yelled at; and the ability to maintain professional boundaries while functioning in a team setting.

Individuals with personality disorders are notably effective at manipulating newer staff. Advice and instructions given to a new caregiver should provide adequate information to permit effective caring and adherence to the behavioral plan. Although it might be tempting to rotate caregivers on a unit or move them to a new unit to provide a break, consistency in staffing with the right people is essential for promoting healing relationships and assuring that behavioral strategies are consistently applied.12

Staff members need continuing education and support to effectively care for these difficult individuals. For frontline caregivers who interact with the resident daily, the job will likely never be easy. Physicians, social workers, and other clinicians need to be mindful of this and take time to understand the perspective, pressures, and needs of frontline caregivers, as this can help ensure that these caregivers are able to carry out the plans for these residents and maintain interactions that are practical and humane.

Aligning Expectations

Aligning expectations is a critical process whereby caregivers, residents’ families, and staff begin to understand one another’s point of view and are able to work together toward the same goals. All parties must understand that individuals with a personality disorder are unlikely to be “cured” in an LTC setting, where they are present to deal with significant medical issues, rather than to receive psychological treatment. Care strategies must be ongoing, gains should be celebrated, and the inevitable setbacks recognized.

Professional staff may be surprised by the vastly different expectations of people with personality disorders. Yelling, hitting, substance abuse, sexual abuse, manipulation, coercion, self-injury, and many other behaviors that are not acceptable in the LTC facility may reflect longstanding habits that previously had been adaptive behaviors for the resident. In the case of antisocial personality disorders, demanding, threatening, and a sense of entitlement are common. Aligning expectations means setting clear boundaries, but it also means assisting the resident to meet underlying needs in a more socially acceptable way. Caregivers should help residents to understand the behavioral expectations of the facility and alter reinforcement so that these residents are rewarded for adherence to standard rules of conduct.

In Mr. A’s case, this began by all caregivers making clear and consistent statements about the behavioral expectations (eg, “It is not OK to yell at the caregivers.”) and the consequences (eg, “If you yell at me, I will have to go away until you calm down.”). He was reminded of the goal, his intention was praised, and specific alternatives were offered both by nursing staff and other interdisciplinary team members, including the physician, social worker, and psychologist. For example, the physician might say something like, “I know you are trying to get the NAs attention and let them know how serious this is to you, but they aren’t the best people to talk to about this problem. Tell me or the social worker and we’ll find a way to address it.”

In the case of a resident with an antisocial personality disorder who is threatening or demanding, saying something like, “We understand you are entitled to the best care we can offer,” clarifies expectations and validates his or her feelings. This needs to be followed up with something like, “This is what I can offer at this time and here are some options outside the facility.” This exchange maintains reasonable boundaries and makes it clear that the resident’s stay at the facility is his or her choice, that the rules are established to protect him or her and others, and that his or her concerns are heard and that there will be a response, but not necessarily the outcome that the resident wants. Threatening such residents with discharge from the facility should be avoided. Despite their obvious dissatisfaction, these residents rarely choose to leave and often have few other residential options. Making threats of discharge from the facility can also increase the patient’s insecurity and damage the therapeutic alliance, which will only exacerbate behavioral problems.

The practice of aligning expectations can be more challenging in the context of person-centered care, where staff are sensitized to trying to accommodate the wishes of care recipients. In Mr. A’s case, for example, caregivers often felt that they should leave the curtain open during care because it was the resident’s wishes or apply rubber bands to his extremities because this was his preference. Educational efforts should focus on helping staff meet all the resident’s needs and some of his or her wants while explaining the difference. Caregivers should be helped to accommodate a few of the patient’s priority wants but to focus mainly on clinical needs.

(Continued on next page)

Team Support

The behavior and reactions evoked by residents with personality disorders in LTC settings may prove exhausting and overwhelming. Personality disordered behavior creates chaos, divisiveness, and confusion. Well-meaning outsiders, including the physician, psychologist, director of nursing, or administrators can enter the system with the intention of helping and inadvertently devalue the team by promoting quick fixes without a clear understanding of the situation.

Physicians and other leadership figures need to be particularly compassionate and supportive of the staff who deliver daily care—believe them, hear them, observe them, identify strengths, provide reasonable explanations that assist in understanding, provide leadership, and highlight successes. Most decisions should be made away from the resident, in a neutral setting where decisions and responses can be more composed. Once a resident has received a diagnosis of a personality disorder, the team needs to proactively address concerns and develop a plan of care that is effective, consistent, and aims to minimize disruptions to the rest of the facility.

Managing Emotions

All members of the team caring for residents with personality disorders should understand that these residents have an ability to incite strong emotions. No matter how centered a clinician or caregiver may generally feel, he or she will still be at heightened risk for reactive responses. Taking one’s own emotional temperature and clarifying individual and team responses can help to mitigate the risk of inappropriate reactions.

Most people desire positive relationships, but persons with personality disorders exhibit lifetime difficulties in doing so. Many, if not all, personality disorders are rooted in or characterized by unbalanced and unhealthy relationships.7,13 Particular concerns include the antisocial and borderline personality disorders. While persons with antisocial personalities will cultivate relationships, these relationships are predominantly instrumental, meaning they are driven by a desire to get what the person wants rather than any real concern for a positive relationship. With borderline personality disorder and its variants, driving a wedge between staff members and self-injury can destroy a relationship by engaging others in unnecessary conflict or by diverting attention to the self-injury. The fear of abandonment, a hallmark of the borderline personality disorder, may surface as staff and peers may react by withdrawing from the resident’s efforts to cling. Modeling appropriate boundaries, emotional control and expressions, and sustaining consistency in the connection with such residents is a great challenge, but is needed to provide the most therapeutic benefits for the resident.

Second opinions are a useful and necessary tool for managing staff reactions, to educate the staff, and to assist in care planning. Care staff may be more sympathetic to a person with a disorder, as opposed to someone simply behaving badly. Staff must be cautious that frustration, fear, anger, or other negative emotions do not come through in tone or body language, in documentation, or in the care decisions that are made. This is much simpler for the physician or psychologist who can walk away from the situation than for caregivers who must remain engaged for an entire shift, day after day, week after week, without a safe place to discharge emotions or receive support. Maintaining a positive and professional demeanor while also setting limits and maintaining appropriate boundaries is the goal. Modeling emotional and behavioral stability for the resident is also one of the most therapeutic interventions available.

Celebrating Small Improvements

It is unlikely that residents with a personality disorder will exhibit major changes in how they interact with others because of their entrenched patterns of behavior. In the LTC setting, these patterns may be compounded by age and by medical and cognitive impairments. Improvements can be difficult to identify. For example, if the staff finds a resident’s behavior irritating 80% of the time and this percentage is reduced to 60%, the staff still feels irritated most of the time, which may not reinforce the improvement. Staff and residents can feel hopeless in these situations, and that feeling may reduce the motivation to employ designated behavioral management strategies.

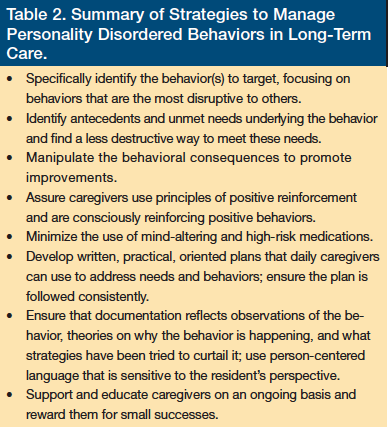

Setting small, realistic goals and celebrating the achievements of the staff and the resident can help diffuse the hopelessness and encourage motivation toward those goals. Praise can be powerful. For example, Mr. A reduced the number of complaints to the administration from more than 20 per month to none for several months, and then he began to direct complaints to the nurse manager and the social worker, rather than to the administration. This enabled his concerns to be directly addressed by persons who were familiar with him and who could focus on his underlying needs. In addition, it decreased the negative impact on the caregiving relationship from the constant threat of “getting in trouble.” When he was able to help a peer in trouble, reduced the number of rubber bands placed on his extremities while being clothed, or had a day without yelling, staff made an effort to tell him that it was noticed and appreciated so that both staff and Mr. A shared in the accomplishments. Table 2 provides a summary of the key strategies discussed here.

Conclusion

Dealing with difficult residents can pose tremendous challenges in LTC facilities, but some of these persons may have an undiagnosed personality disorder. Identifying such persons is crucial, as strategies can be implemented to curtail some of their troubling and undesirable behaviors. Generally, behavioral management strategies, such as the ABC model described in this article, are the best approach, rather than the use of medication. When developing interventions, input from the entire team is required and these interventions should focus on positive reinforcement by rewarding the patient for following rules, rather than on punishment for breaking them. Continued staff support and education on the resident’s personality disorder are also essential, as this prevents the staff from harboring ill feelings toward the resident and enables them to have a greater tolerance when confronted with the resident’s deviant behaviors.

Caring for persons with personality disorders can be time-consuming, frustrating, and at times emotionally exhausting, but can also be rewarding because teams of committed people can make a difference in the lives of these deeply troubled individuals. In addition, these patients push us to be our very best and help us reflect on the reasons we chose healthcare, causing us to develop humility about our abilities to deliver care and to see the humanity in others.

References

1. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(16):

883-887.

2. Kernberg OF. Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism. New York, NY: Jason Aronson; 1975.

3. Stewart JT. The frontal/subcortical dementias: common dementing illnesses associated with prominent and disturbing behavioral changes. Geriatrics. 2006;61(8):

23-27.

4. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198.

5. Chodosh J, Edelen MO, Buchanan JL, et al. Nursing home assessment of cognitive impairment: development and testing of a brief instrument of mental status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(11):2069-2075.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

7. Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(6):553-564.

8. Bender E. Personality disorder prevalence surprises researchers. Psychiatric News. 2004;39(17):12-40.

9. Kernberg OF. Aggression In Personality Disorders and Perversions. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1992.

10. Stone MH. Management of borderline personality disorder: a review of psychotherapeutic approaches. World Psychiatry. 2006;5(1):15-20.

11. Deutsch H. Some forms of emotional disturbance and their relationship to schizophrenia. 1942. Psychoanal Q. 2007;76(2):325-344; discussion 345-386.

12. Farrell D. Consistent assignment: the prerequisite for individualized care. www.theconsumervoice.orghttps://s3.amazonaws.com/HMP/hmp_ln/imported/family-member/Fall-R1-PPT-Consistent-Assignment-Farrell.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2012.

13. Horner AJ. Object Relations and the Developing Ego in Therapy. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 1989.

Disclosures:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to:

Robert Gibson, PhD, JD

655 Park Center Drive

Santee, CA 92071

Robert.Gibson@sdcounty.ca.gov