Diagnosing the Cause of Progressive Dyspnea in an Elderly Man

Affiliations:

1Geriatrics fellow, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC

2Program director, Geriatric Medicine Fellowship, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, MA

A frail 78-year-old man with a medical history significant for smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and peripheral vascular disease presented to the hospital with a chief concern of subacute, progressive dyspnea. This was preceded by weakness, anorexia, and weight loss. He did not have any coughing, wheezing, chest pain, lower limb edema, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, fevers, chills, or night sweats. He was not on any inhaler therapy at home.

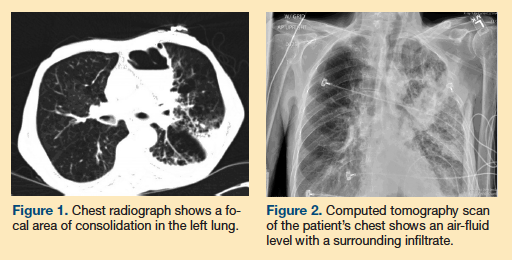

His initial vital signs were significant for a heart rate of 105 beats per minute, blood pressure of 104/76 mm Hg, and an oxygen saturation level of 93% on room air. Significant physical examination findings included cachexia and a sacral ulcer. His lungs showed vesicular breath sounds with crackles in the left upper lobe. Laboratory values indicated no leukocytosis, and his electrolyte panel, blood urea nitrogen level, and creatinine level were all within normal limits. A radiograph (Figure 1) and computed tomography (CT) scan of his chest (Figure 2) showed significant findings.

Based on the clinical presentation and the imaging findings, what is your diagnosis?

A. Infected emphysematous bulla

B. Lung abscess

C. Hemorrhagic bulla

D. Congestive heart failure

E. Malignancy

Answer on next page

Answer: Infected emphysematous bulla (A)

Based on the patient’s clinical history and radiological findings, a diagnosis of an infected emphysematous bulla was made. A lung bulla is an air-filled space that occurs after destruction of the alveoli, specifically a rupture of the alveolar septum.1 An infected emphysematous bulla is an uncommon complication of COPD. The literature is limited to case reports and case series, many of which were published before 2000. In most of the cases described in the literature, the diagnosis is made based on the patients’ clinical history of pleuritic chest pain and constitutional signs of infection, along with a chest radiograph showing an air-fluid level contained within a bulla.2-4 Many patients also present with cough. The presence of a bulla in the same location on a prior chest radiograph strengthens the diagnosis.4-6 The differential diagnosis is broad, and it includes lung abscess, hemorrhagic bulla, granulomatous disease, tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia, congestive heart failure, and malignancy. We discuss several of these diagnoses later in the article.

In the literature, percutaneous drainage has been used to obtain culture data, however, there is no clear consensus on when it is indicated. Culture data has revealed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Bacteroides, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, alpha-hemolytic Streptococcus, and Haemophilus influenzae. In some cases, culture-negative samples were retrieved; however, they had all been obtained after antibiotics were administered.2-4,6 Bronchoscopy and sputum culture have been performed on a number of patients, but these interventions did not alter the diagnosis, change management, or improve drainage, and were therefore not found to be beneficial.2

Approaches to Treatment

Cases of infected emphysematous bullae dating back to the 1980s were commonly treated with prolonged courses of penicillin.3,5 More recently, broad-spectrum antibiotics from every drug class that treat community-acquired pneumonia have been used.2,6 One case cites success with cefuroxime and erythromycin.7

Case Patient Outcome

Our case patient was started on ceftriaxone and azithromycin. Tuberculosis was ruled out after administering a purified protein derivative test and T-Spot test. Cultures for Aspergillus and Histoplasma capsulatum were negative, as was a screening for respiratory viruses using a direct fluorescent-antibody assay. The patient’s condition worsened during the course of his work-up; his respiratory rate increased and he developed hypoxia requiring bilevel positive airway pressure for ventilation. Laboratory markers of infections continued to show no significant findings. Serial chest radiographs showed progression of the left upper lobe effusion. Antibiotics were broadened to vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam.

We had extensive discussions with the patient and his healthcare proxy about the goals of care, his disease process, and his overall poor prognosis. The patient decided to remain full code. He was admitted to the intensive care unit and intubated for impending respiratory failure. He subsequently developed septic shock requiring vasopressors. Eight days later, his healthcare proxy shifted the goals of care to provide comfort measures only, and the patient died.

Differential Diagnosis

What follows is a discussion of some of the other possible diagnoses, which were ruled out for our case patient. These included lung abscess, hemorrhagic bulla, congestive heart failure, and malignancy.

Lung abscess. A lung abscess can present similarly to an infected bulla, with constitutional signs of infection and progressive respiratory symptoms. Imaging studies with a chest radiograph and CT scan would demonstrate a thick, walled-off cavity containing pus and necrotic tissue. It is differentiated from a bulla by the thickness of its walls (ie, bullae walls are <1 mm).8 Pathogens commonly isolated include gram-negative rods and oral flora. Gram-negative rods may include Fusobacterium, Bacteroides fragilis, and Klebsiella pneumoniae, whereas oral flora may include Fusobacterium nucleatum, Fusobacterium necrophorum, and Clostridium perfringens.9 Treatment includes broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as beta lactam, to cover mixed flora, or a combination of penicillin with anaerobic coverage, such as clindamycin or metronidazole.9

Hemorrhagic bulla. A hemorrhagic process complicating an emphysematous bulla is rare, with few cases reported in the literature.10-12 All cases presented with hemoptysis with or without pleuritic chest pain and hemorrhagic shock. Laboratory studies may show acute anemia. Treatment in these cases was patient-dependent. The approaches included using fresh-frozen plasma (to reverse a supra-therapeutic international normalized ratio from chronic warfarin use) combined with positional drainage10; and immunosuppression for newly diagnosed acquired hemophilia.11

Congestive heart failure. A congestive heart failure exacerbation commonly presents with progressive shortness of breath, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. The physical examination findings typically show extra heart sounds, elevated jugular venous pressure, bibasilar lung crackles, and lower limb edema. Chest imaging shows pleural effusions resulting from increased interstitial fluid in the lungs. The presence of an air-fluid level within a bulla in patients who have underlying COPD with an exacerbation of congestive heart failure has previously been reported.13,14 In two cases, patients presented with the typical signs and symptoms of heart failure, as previously discussed.13,14 In addition to the previously described chest radiography findings, an air-fluid level within a lung bulla was also seen. All patients were treated with loop diuretics, and follow-up imaging showed resolution of the initial pathology.

Malignancy. Patients with emphysematous bullae have a higher incidence of lung cancer.14 Other risk factors are male sex and a history of smoking. Malignant emphysematous bullae can be found incidentally during a bullectomy or may present with hemoptysis or spontaneous pneumothorax.15-17 Pathologically, large cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma make up the majority of cases diagnosed, although squamous cell carcinoma and small cell carcinoma have been reported as well.15-20 In these cases, the cancer was at varying stages of detection, and prognosis varied depending on the stage.

References

1. Klingman RR, Angelillo VA, DeMeester TR. Cystic and bullous lung disease. Ann Thoracic Surg. 1991;52(3):576-580.

2. Chandra D, Rose SR, Carter RB, Musher DM, Hamill RJ. Fluid-containing emphysematous bullae: a spectrum of illness. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(2):303-306.

3. Peters JI, Kubitschek KR, Gotlieb MS, Awe RJ. Lung bullae with air-fluid levels. Am J Med. 1987;85(4):759-763.

4. Chandra D, Soubra SH, Musher DM. A 57-year-old man with a fluid-containing lung cavity. Chest. 2006;130(6):1942-1946.

5. Leatherman JW, McDonald FM, Niewohner DE. Fluid-containing bullae in the lung. South Med J. 1985:78(6):708-710.

6. Kalra N, Aiyappan SK, Jindal SK, Khandelwal N. Image-guided percutaneous drainage of an emphysematous bulla with a fluid level. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2010;20(1):34-36.

7. Richardson MSA, Reddy VD, Read CA. New air-fluid levels in bullous lung disease: a reevaluation. J Natl Med Assoc. 1996;88(3):185-187.

8. Meholic A, Ketai L, Lofgren R. Fundamentals of Chest Radiology. 1st ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company;1996:62.

9. Goldman L, Ausiello D, eds. Cecil Medicine. 23rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier, 2008:685-688.

10. Trzciński M, Folcik K, Burakowska B, Błasińska K, Wiatr E. The bleeding into the emphysematosus bulla imitating lung tumor [in Polish]. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2012;80(3):275-279.

11. Thomas DW, Balikai G, Nokes TJ. Bleeding into an emphysematous bulla. Br J Haematol. 2008;141(1):1.

12. Nagashima O, Suzuki Y, Iwase A, Takahashi K. Acute hemorrhage in a giant bulla. Intern Med. 2012;51(18):2673.

13. Rabinowtiz JG, Kongtawng T. Loculated interlobular air-fluid collection in congestive heart failure. Chest. 1978;74(6):681-683.

14. Lewis JD. Multiple pulmonary air fluid levels as a presentation of congestive heart failure. Chest. 1995;108(6):1745-1746.

15. Hirai S, Hamanaka Y, Mitsui N, Morifuji K, Sutoh M. Primary lung cancer arising from the wall of a giant bulla. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;11(2):109-113.

16. Hatakeyama S, Tatibana A, Suzuki K, Kobayashi R. Five cases of lung cancer with emphysematous bullae [in Japanese]. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2001;39(6):415-418.

17. Nakamura H, Takamori S, Miwa K, et al. Rapid-growth lung cancer associated with a pulmonary giant bulla: a case report. Kurume Med J. 2003;50(3-4):147-150.

18. Venuta F, Rendina EA, Pescarmona EO, et al. Occult lung cancer in patients with bullous emphysema. Thorax. 1997;52(3):289-290.

19. Arab WA, Echavé V, Sirois M, Gomes MM. Incidental carcinoma in bullous emphysema. Can J Surg. 2009;52(3):E56-E57.

20. Shin H, Oda M, Matsumoto I, et al. Lung adenocarcinoma originated from bulla wall accompanying spontaneous hemopneumothorax; report of a case [in Japanese]. Kyobu Geka. 2010;63(3):245-247.

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to: Shiv Khosla, Durham VA Medical Center, Box 182, 508 Fulton Street, Durham, NC 27701; shiv.khosla@duke.edu

This article was originally published in Clinical Geriatrics on November 18, 2013.