Dementia and Palliative Care

Many patients with dementia benefit from palliative care at the end of life, an interdisciplinary approach1 that applies a treatment philosophy of “coping,” rather than “curing,” for patients with an advanced or terminal illness. Palliation envisions the final phase of life as peaceful, dignified, and as free from suffering as possible, with death viewed as an inevitable consequence of terminal illness to be managed thoughtfully once the outcome becomes clear.2 To achieve this, the palliative approach emphasizes symptom management, psychosocial support, communication, and coordination of care.3,4 Intensive or intrusive medical interventions considered futile or having serious potential for harm are avoided, and the focus is instead on relieving pain and suffering.1 When adopting a palliative approach, it is important for providers to be aware of the many ethical and spiritual issues that can arise in conjunction with end-of-life care.

Studies show that optimally managing frequently experienced syndromes of pain, grief, fatigue, and insomnia can greatly improve quality of life for terminally ill patients.2,5 Psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, eating problems, psychoses, and delirium, increase suffering and also require careful attention.4-7 An effective palliative approach encompasses grief and bereavement support for the patient, his or her family, and the treatment team.

Despite shifting the focus away from finding a cure, the palliative approach does not exclude all disease-modifying therapies. In fact, the palliative continuum of care balances disease-modifying and palliative treatments based on an individualized treatment plan. In some cases, disease-modifying therapies (eg, antibiotics) represent the best method for reducing suffering. Although dementia-specific drugs such as cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine are available, these do not correct the underlying pathologies (eg, Alzheimer’s disease [AD]) or change outcomes and are best viewed as supportive rather than disease-modifying therapies. In this paper, we focus on dementia as an example of a terminal condition in which palliative care practices can be helpful.

Disease Progression and Mortality in Dementia

Patients with dementia are typically elders who have concomitant medical conditions, and many suffer great emotional distress and physical pain. Most dementias encountered in this population are incurable, progressive, and markedly reduce life expectancy. In one study,8 patients with AD survived a median of 4.5 years after diagnosis. Dementia is regarded as a terminal disorder, regardless of the final cause of death, which is frequently a comorbid medical condition, such as sepsis.9 Physicians and families often fail to realize the deleterious effect of dementia on life expectancy. A study of dementia in US nursing homes found that staff thought only 1% of their dementia residents had a life expectancy of <6 months, yet 71% of these residents died within that timeframe.10

The traditional approach for treating comorbid medical conditions in patients with dementia is definitive management, despite the presence of dementia. This approach is most effective with a motivated, cooperative patient who is able to participate in treatment planning and decision-making; however, many patients with advanced dementia are unable to make such decisions, express their preferences, or participate in their own care. Instead, these patients may resist medical procedures, requiring sedation or restraints, which carry their own risks.

When treating serious medical conditions in patients with dementia, physicians often find themselves in conflict with family surrogate decision makers regarding the ethics of providing versus withholding intensive treatments for their dependent relative. Providing education, access to counseling, and spiritual support for families is part of the palliative care approach, and ideally a palliative care team would handle these complex and often emotional discussions with families.

Minimizing the Medical Burden on Patients

Acknowledging the terminal nature of dementia, especially advanced dementia, permits a shift to palliative care. The palliative approach emphasizes relief from suffering in the near term and recognizes that aggressive or intrusive interventions for comorbid medical conditions may be fruitless or even counterproductive in these patients.

A shift to palliation should lead to a review of treatment goals when considering any diagnostic procedures, hospitalizations, and medications for existing and newly emergent medical conditions. Hospitalization, in particular, is risky for patients with dementia, increasing the likelihood of falls, delirium, restraint-related injuries, over-sedation, and adverse effects associated with various medical procedures.

Risks of Polypharmacy

Many elders take a variety of medications to manage chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and osteoporosis. For individuals having a typical lifespan, this provides optimum management and helps prevent significant events such as myocardial infarction or stroke, thereby improving health outcomes and increasing longevity. However, polypharmacy increases the likelihood of drug interactions, with the risk of drug-drug interactions increasing as the number of medications used increases. For example, highly protein-bound drugs (eg, fluoxetine) may increase the active fraction of commonly prescribed medications such as warfarin or digoxin; and many selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) interact with other drugs via a cytochrome P450 pathway. A large medication burden commonly causes delirium, cognitive decline, and loss of appetite.11 Such adverse events are of particular concern in patients with advanced dementia and a limited lifespan, for whom the putative benefits of aggressive treatment are often less evident.

Practice guidelines, designed to promote state-of-the-art medical care, may inadvertently promote polypharmacy in the elder with dementia and provide a false sense of comfort to physicians, who proceed to prescribe even more medication to their patients, believing that their knowledge and practices fall within the bounds of recognized expert opinion. Guidelines for managing conditions common in the elderly population, such as diabetes, osteoporosis, and hyperlipidemia, are designed not only to promote symptom relief, but also to reduce the risk of long-term complications. They often recommend increasingly complex regimens and fail to countenance that someone with dementia may have multiple conditions that interact or that, given the reduced life span associated with dementia, the negative effects of intensive treatment may outweigh the long-term benefits.12

Certain medications are generally considered contraindicated in patients with severe dementia. In particular, anticholinergics and long-acting benzodiazepines should be avoided and antipsychotics should be used sparingly. Dementias, particularly AD, reflect a state of cholinergic deficiency that is exacerbated by even modest amounts of anticholinergic medication.13 Although the anticholinergic effect of an individual drug may be minimal, the cumulative anticholinergic burden of multiple medications may be problematic for patients with dementia.14 Each situation requires a careful risk-benefit analysis. For example, many medications for urinary incontinence are anticholinergics, yet their use may enhance a patient’s quality of life; and clonazepam, a long-acting benzodiazepine, can suppress rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior syndromes, but potential adverse effects include ataxia and cognitive impairment.

Put simply, considering the relatively short lifespan of patients with advanced, incurable dementia, the limited benefits many medications offer are outweighed by their potential adverse effects. Thus, when taking a palliative approach, the focus of therapeutic efforts should be to manage symptoms that detract from quality of life in the near term, using the least amount of medication and fewest interventions necessary.

Feeding Tubes

The limited value of feeding tubes is a topic worth considering. Several studies have demonstrated the futility of using feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia.15 Contrary to expectations, providing nutritional support has generally not been found to extend life or prevent complications such as aspiration. Feeding tubes can themselves become a source of complications, with some dementia patients having to be sedated or restrained to prevent them from removing the tube. The highly variable history and circumstances of each clinical situation demand a case-by-case approach to decision-making, which involves value judgments and medical judgments. In general, however, feeding tubes have little place in advanced dementia care.15

Pain Management in Dementia

Pain is common in dementia patients16 and in the general nursing home population, with various studies showing that 45% to 80% of nursing home residents report pain problems.17 Common causes of pain include malignancy, musculoskeletal problems (eg, arthritis, degenerative conditions of the spine), neuropathies, gastrointestinal issues, and headache.16 Of note, several reports indicate that minority patients are less likely to have their pain documented and black patients are less likely to receive analgesia than white patients. A study of cancer pain in minority patients found that many felt they needed more analgesics than their physicians had prescribed.18

Despite the high prevalence of pain in patients with dementia, it is poorly recognized and managed.19 Patients with dementia may lack the verbal skills to communicate their pain, which may be evident only through observation of behavioral changes. Physicians are not always cognizant of pain issues in their dementia patients or sometimes take a nihilistic approach to the problem, thinking nothing can be done or that pain medicine is contraindicated in dementia. Managing pain effectively for these patients involves several principles, including attending to self-reports, searching for causes of pain, observing behavior, and attempting an analgesic trial.

Assessing Pain

Common features of dementia, such as memory impairment, executive dysfunction, aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia, may impair the ability of the patient to express pain and of the physician to assess it.20 Dementia patients may also have difficulty recognizing and communicating internal states and may have impaired memory for pain. It is possible that the neuropathology of dementia interacts in unknown ways with neural pain circuits, and emotional states in dementia may persist even when the patient cannot describe or recall the inciting event.

Assessing pain in a dementia patient who has limited verbal communication is possible through physical examination and the use of simple verbal and nonverbal tools and various scales. Detecting pain requires focusing on behavioral changes, mood symptoms, facial expressions, and body language. Behavioral changes may include restlessness, fidgeting, resistance to care, decreased movement, aggression, and shouting or screaming. Mood symptoms include depression, withdrawal, anger, and diminished appetite. Facial expressions indicative of pain include grimacing, frowning, fear, and tension. Pain clues from body language include rubbing, bracing, guarding, or holding the affected area.20 Using some type of pain scale (eg, Doloplus-2, which is available at https://prc.coh.org/PainNOA/Doloplus%202_Tool.pdf) is likely to increase recognition of pain and promote its management in patients with dementia.21

Treatment Options

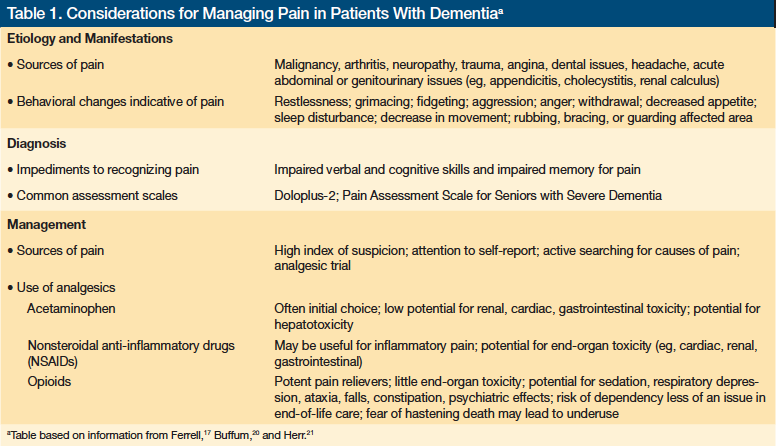

Treatment considerations for relieving pain in patients with dementia include acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and opioids (Table 1).17,20,21 The choice of pain medication in dementia presents a number of dilemmas requiring an assessment of risk versus benefit.

Acetaminophen is often an appropriate first choice, given its relatively low potential for renal, cardiac, and gastrointestinal toxicity relative to NSAIDs. The potential of hepatic toxicity with acetaminophen use requires attention to dosing, and caution should be taken not to overlook the acetaminophen present in pain relievers that combine the compound with narcotics or other active drugs. NSAIDs may be more effective at ameliorating inflammatory pain, but they present more toxicity concerns, and their use must be closely monitored. Neuropathic type pain may respond to antidepressants or anticonvulsants.17,20,21

Opioids are more potent pain relievers, and their effectiveness and lack of end-organ toxicity compared with that of NSAIDs may make them an appropriate choice for some patients. Sedation, ataxia, falls, psychiatric side effects, constipation, and orthostatic hypotension are important considerations with opioid use. Pain appears to contribute to agitation in many dementia patients, and recent studies have suggested that pain management including opioids can reduce agitation.22 In the context of dementia and reduced life expectancy, dependency is less of a concern. However, many physicians remain uneasy about using opioids, and these drugs are likely underused in this population. A cautious approach to opioid dosing is recommended and requires beginning with low doses and carefully observing the patient for adverse effects. When discussing opioid use with the patient and his or her family, physicians can dispel the myth that properly administered opioids hasten death.

When pain is thought to be persistent, a regular dosing schedule is recommended over an “only as-needed” approach. A lack of consensus among physicians and various members of the nursing staff who encounter the patient over time may hinder as-needed dosing schedules, with different providers responding differently to the same written orders.

Management of Psychiatric Issues

End-of-life psychiatric symptoms or syndromes are common in patients with dementia, and pharmacologic therapies may be indicated to relieve symptoms in those assigned to palliative care.23 For example, low-dose antipsychotics can help alleviate psychotic symptoms or agitation. Antidepressants can be prescribed to treat depressive symptoms or anxiety. Some patients or even their families may also benefit from psychotherapy.

Dosing of psychiatric medications is typically conservative, with clinicians adopting a “start low and go slow” philosophy. How long to use a particular psychiatric agent is dictated by the degree of improvement achieved in the underlying symptoms that the drug is being used to treat and the persistence of symptoms. Sedation is usually not the goal of treatment, but often a consequence of using therapeutic medications to relieve agitation. As is the case with managing pain in patients with dementia, managing agitation requires balancing risks versus benefits. Targeted symptoms evolve over time, and the use of pharmacologic therapies to treat psychiatric symptoms requires periodic assessment (eg, at 3-month intervals) of risks and benefits, with an eye on stopping or weaning patients off medications that are no longer indicated.

Delirium

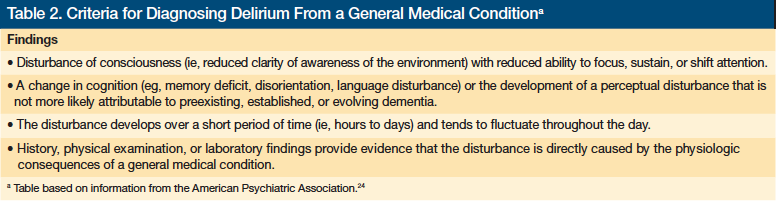

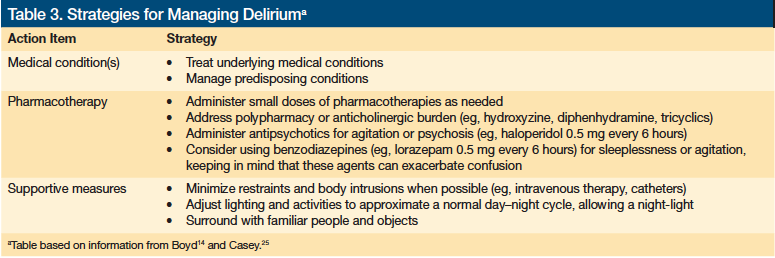

Delirium is a common complication in severely ill patients, especially those with dementia (Tables 2 and 3).12,24,25 Delirium can be a source of great distress not only to patients, but also to their families and to the treatment team. Although delirium is generally considered a medical condition, it has psychiatric manifestations and psychiatric medications are often used in managing delirium.

A condition known as “terminal delirium” is often encountered in the last days or hours of life and may be a harbinger of death. Marked restlessness is sometimes observed, eliciting the term “terminal restlessness.” Definitive therapy for delirium typically involves resolving the underlying illness. Because this is not possible for most patients with a terminal illness, palliative management of terminal delirium focuses on relieving symptoms, addressing pain, and reducing agitation. Small doses of antipsychotic medications (eg, haloperidol 0.5 mg every 6 hours or risperidone 0.25 mg-0.5 mg twice daily) may be useful. Small doses of benzodiazepines are sometimes used to relieve anxiety or restlessness (eg, lorazepam 0.25 mg-0.5 mg every 6 hours as needed), but benzodiazepines have been shown to prolong delirious episodes. For patients clearly in the last hours of life, minor restlessness may not require intervention.26

Depression

Depression is common in palliative and hospice care patients and is frequently seen in patients with dementia. The prevalence of depression in patients with a terminal illness varies widely by study.6,27,28 Managing depression appropriately markedly improves patients’ quality of life, and various approaches are available for consideration.

Limited information is available to guide the clinician on the selection and dosing of antidepressants in dementia, and outcome data are contradictory. SSRIs such as citalopram (initial dose range, 10 mg-20 mg/day) are commonly used as first-line pharmacologic agents, with newer medications such as serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) used in the second-line.29 Stimulants, such as methylphenidate (initial dose typically 5 mg/day), may be helpful for regressed, apathetic, or severely withdrawn medically ill patients and can be administered alone or with an antidepressant.30 Mirtazapine, an SNRI, is also prescribed to address anorexia (initial dose range, 7.5 mg-15 mg nightly before bed), as are other drugs that stimulate appetite, such as megestrol acetate.31

Sleep Disturbances

Sleep disturbances and sundowning are common in dementia patients nearing the end of life. Parasomnias and dyssomnias, including obstructive sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome, nocturnal myoclonus, and REM sleep behavior disorders, can interfere with sleep in patients with dementia and may require therapy. Although a wealth of clinical experience is available to guide treatment for sleep disturbances in adults, studies on treating sleep disturbances specific to dementia patients are lacking.

Sedating antidepressants, such as trazodone (initial dose, ~50 mg nightly before bed) or mirtazapine (initial dose, 7.5 mg-15 mg nightly before bed), are an option for reducing anxiety and improving sleep disturbances. Sedating tricyclic antidepressants, such as amtriptyline or doxepin (typically in the initial range of 25 mg nightly before bed), have been used to induce sleep, but these have undesirable anticholinergic and cardiovascular effects and should generally not be used in this patient population. Hypnotics, such as zolpidem (initial dose, 5 mg nightly before bed), are sometimes used, but these agents are typically recommended for short-term treatment, whereas sleep disturbances in dementia patients may be prolonged and require ongoing therapy. Benzodiazepines are another option, and generally short- or intermediate-acting ones like lorazepam (initial dose, 0.25 mg-0.5 mg every 6 hours) are used; long-acting benzodiazepines such as clonazepam heighten the risk of falls and cognitive clouding and are usually avoided.

Over-the-counter sleep aids often contain a sedating antihistamine known as diphenhydramine, which has anticholinergic properties, and should generally be avoided in patients with dementia. An empirical trial of melatonin (typically 3 mg-6 mg nightly before bed) may be attempted.32,33

Psychotherapy

Many types of psychotherapy are potentially useful, including supportive, cognitive, and existential therapies. Continued therapy for bereaved family members may be warranted after the patient dies.8 Consultations with psychiatrists may also help staff in understanding and coping with difficult patient behaviors and family interactions,10 and such sessions should explore divergent approaches to illness and death among different cultures. Psychiatrists are sometimes called on to evaluate the decision-making capacity of patients suffering from incurable or terminal illnesses. Making such determinations can be difficult and controversial, requiring clinical expertise and knowledge of mental health law.34,35

Conclusion

Adopting a palliative care approach to manage end-of-life care issues in patients with a terminal illness can help prevent unnecessary suffering. This is especially important for patients with dementia, whose condition may not be recognized as terminal and are thus subjected to overtreatment with therapies that offer few benefits and a substantial risk of adverse effects. Pain and psychiatric syndromes are common in dementia patients, yet they often go unrecognized or untreated. Appropriately managing these secondary conditions are essential to ensuring that these patients receive humane care.

1. World Health Organization. Palliative care. 2011. www.who.int/cancer/palliative/en/. Accessed November 22, 2011.

2. Chochinov HM, Breitbart W. Handbook of Psychiatry In Palliative Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000: 150-165.

3. McGrath P, Holewa H. Mental health and palliative care: exploring the ideological interface. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation. 2004;9(1):107-119.

4. Lyness JM. End-of-life care: issues relevant to the geriatric psychiatrist. Am J Geriatr Psych. 2004;12(5):457-482.

5. Tang W, Aaronson L, Forbes S. Quality of life in hospice patients with terminal illness. West J Nurs Res. 2004;26(1):113-118.

6. Irwin SA, Rao S, Bower K, et al. Psychiatric issues in palliative care: recognition of depression in patients enrolled in hospice care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):158-163.

7. Keeley PW. Delirium at the end of life. Clin Evid (online). 2007. pii:2405.

8. Xie J, Brayne C, Matthews FE; Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study collaborators. Survival times in people with dementia: analysis from population based cohort study with 14 year follow-up. BMJ. 2008;336(7638):258-262.

9. Purtilo RB, ten Have H, eds. Ethical Foundations of Palliative Care for Alzheimer’s Disease. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

10. Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel BK, Park PS, Morris JN, Fries BE. Estimating prognosis for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2734-2740.

11. Lau DT, Mercaldo ND, Harris AT, Trittschuh E, Shega J, Weintraub S. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use among community-dwelling elders with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24(1):56-63.

12. Tune LE. Anticholinergic delirium: assessing the role of anticholinergic burden in the elderly. Curr Psychos Ther Rep. 2004;2(1):33-36.

13. Casey DA. Pharmacological management of behavioral disturbance in dementia.

J Clin Pharm Ther. 2007;32(10):560-566.

14. Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases. JAMA. 2005;294(6):716-724.

15. Li I. Feeding tubes in patients with severe dementia. Am Fam Phys. 2002;65(8): 1605-1610, 1515.

16. Kim KY, Yeaman P, Keene R. End-of-life care for persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(2):139-141.

17. Ferrell BA. Pain evaluation and management in the nursing home. Ann Int Med. 1995;123(9):681-687.

18. Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Baez L, Loehrer P, Pandya KJ. Pain and treatment of pain in minority patients with cancer. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Minority Outpatient Pain Study. Ann Intern Med. 1997;1276(9):813-816.

19. Evers MM, Purohit D, Perl D, Khan K, Marin DB. Palliative and aggressive end-of-life care for patients with dementia. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(5):609-613.

20. Buffum MD, Hutt E, Chang VT, Craine MH, Snow AL. Cognitive impairment and pain management: review of issues and challenges. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44(2):315-330.

21. Herr K, Coyne PJ, Key T, et al; American Society for Pain Management Nursing. Pain assessment in the nonverbal patient: position statement with clinical practice recommendations. Pain Manag Nurs. 2006;7(2):44-52.

22. Husebo BS, Ballard C, Sandvik R, Nilsen OB, Aarsland D. Efficacy of treating pain to reduce behavioural disturbances in residents of nursing homes with dementia: cluster randomized clinical trial. BMJ. 2011;343:d4065.

23. Dein S. Psychiatric liaison in palliative care. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2003;9(4):241-248.

24. American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2000:143.

25. Casey DA, DeFazio JV Jr, Vansickle K, Lippmann SB. Delirium: quick recognition, careful evaluation, and appropriate treatment. Postgrad Med. 1996;100(1):121-124,133-134.

26. Fine RL. Depression, delirium and anxiety in the terminally ill patient. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Center). 2011;14(2):130-132.

27. Draper B. The diagnosis and treatment of depression in dementia. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(9):1151-1153.

28. Lloyd-Williams M, Friedman T. Depression in palliative care patients: a prospective study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2001;10(4):270-274.

29. Block SD; ACP-ASIM End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel; American College of Physicians; American Society of Internal Medicine. Assessing and managing depression in the terminally ill patient. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(3):209-218.

30. Rozans M, Dreisbach A, Lertora JJ, Kahn MJ. Palliative uses of methylphenidate for patients with cancer: a review. J Clin Onc. 2002;20(1):335-339.

31. Jatoi A. Pharmacologic treatment for the cancer/anorexia weight loss syndrome: a data-driven, practical approach. J Support Onc. 2006;4(10):495-502.

32. Deschenes CL, McCurry SM. Current treatmensts for sleep disturbances in individuals with dementia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11(1):20-26.

33. Vitiello MV, Borson S. Sleep disturbances in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2001;15(10):777-796.

34. Terman SA. Evaluating the decision-making capacity of a patient who refused food and water. Palliat Med. 2001;15(1):55-60.

35. Tan ZS. A piece of my mind: the “right” to fall. JAMA. 2010;303(23):2333-2334.