Delirium Knowledge Improvement and Implementation of the RADAR Screening Tool in Two Skilled Nursing Facilities

Delirium in skilled nursing facility patients is underrecognized and linked to poor patient outcomes. Nurses in the skilled nursing setting do not use a standardized tool for assessing delirium, but the literature suggests they routinely should. The purposes of this study were to evaluate methods for improving the management of delirium in skilled nursing and to evaluate implementation of the new Recognizing Active Delirium As part of your Routine (RADAR) screening tool. The study included implementation of a delirium education program and established routine use of the RADAR tool. This pilot study found that an education session can improve nurse knowledge of delirium. The study also demonstrated reliable administration of the RADAR screening tool. These findings suggest that methods used for this project could have implications for improving the care of patients in the skilled nursing setting at risk for delirium.

Key words: delirium, screening tool, skilled nursing, long-term care

Delirium, a condition occurring in older adults across the health care continuum, is frequently underrecognized, especially in the skilled nursing facility (SNF) setting.1 In the SNF setting, delirium has an incidence of 34%.2 For patients admitted to an SNF with delirium, the mortality rate at 1 year is 34%.3 In addition to a high mortality rate, delirium is associated with significant morbidity, high cost, and functional loss.4 According to Marcantonio et al, one-third to two-thirds of patients with delirium are not diagnosed with the condition; therefore, the underlying cause is neither identified nor treated.5 In long-term care specifically, delirium goes unrecognized in 49% to 87% of cases.1,6 Underdiagnosing such a large percentage of older adults affected by this costly and deadly disorder is not only detrimental to the population but also an expensive burden to the health care system. Patients with delirium often require additional or more complex care than is readily available in the high patient-to-staff ratio environment of many SNFs.3

Addressing the problem of underdiagnosis in the SNF setting starts with improving the knowledge of staff providing direct care. No established, effective model of care for delirium exists for use in the SNF setting. However, experts have identified the components needed for a delirium education model, which include support from administration and users, effective clinical leadership to ensure proper delivery and appropriate adaptation, a sense of ownership among users, and practical, hands-on staff training.7 No improvement in prevention or detection can occur if nurses at the bedside are not knowledgeable about delirium and skilled in assessment of the disorder.

After effective education, the next step to improving delirium recognition in SNF patients is reliable screening. The most widely used tool for detecting delirium is the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).8-11 The CAM has proven to be challenging to implement in the SNF setting, though, because of barriers involving time, ease of use, and generalizability.12 Voyer et al developed the Recognizing Acute Delirium As part of your Routine (RADAR) screening tool for use in acute care and SNF settings with the intent to erase the barriers posed by the CAM.12

The RADAR validation study was conducted in Canada.12 In 2015, the study was published, with RADAR demonstrating a sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 67% when compared with delirium criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, Text Revision.12,13 The RADAR consists of 3 questions about the patient’s condition: (1) Was the patient drowsy? (2) Did the patient have trouble following your instructions? and (3) Were the patient’s movements slowed down?12 A positive answer to any one question indicates a positive screening for delirium and the need for further investigation.12

The purpose of this study was to measure the impact of education on nurse knowledge of delirium in the SNF setting and to evaluate the feasibility of using the RADAR screening tool in 2 SNFs in the United States.

Methodology

This study was a 3-month, pre- and post-test quasiexperimental study that evaluated several variables: (1) scores from one pre-education test and 2 post-education tests; (2) interrater reliability; (3) nurse perception of the RADAR tool; and (4) nurse demographics.

Approval for the study was received from the Belmont University Institutional Review Board.

Study Participants

Participants in the project were nurses providing direct patient care at 2 urban postacute/long-term care facilities in the United States. One facility had a capacity of 240 patients, and the other facility had a capacity of 180 patients. Inclusion criteria for the project were nurses who worked full or part time and provided direct patient care. Exclusion criteria were nurses not providing direct care or not permitted to administer regularly scheduled medications.

Design

The principle investigator, a gerontologic nurse practitioner, provided mandatory education sessions for all nurses at both facilities. The sessions included general delirium education and a video on administering the RADAR that included case vignettes.14 While the inservices were mandatory, participation in the project was optional. Nurses in the study completed a pre-education test and demographic questionnaire and then attended the same education session as nurses who chose not to participate in the study.

The RADAR tool, originally in paper format, was incorporated into the electronic medical record (EMR) because both facilities use EMR exclusively for documentation. Image 1 shows a portion of the paper-based RADAR screening tool. After nurses completed the education, they incorporated the RADAR tool into their daily routine with all patients. Bedside nurses administered RADAR screening to all patients once per shift during medication administration during the 3-month study, and results were recorded on the medication administration record.

Article continues below Image

After the nurses had used the RADAR tool for 2 months, the principle investigator measured their accuracy in using the tool and determined interrater reliability. At the completion of the study, a dichotomous questionnaire was administered to assess nurse perception of the RADAR tool. The principle investigator conducted 117 interrater reliability assessments during the nurses’ medication administration and RADAR screening.

The principle investigator provided support through biweekly rounding with the nursing staff. This strategy provided opportunities to answer nurses’ questions and to reinforce delirium education. Facility stakeholders supported making education sessions mandatory and implementing RADAR screening of all patients at both facilities during the 3-month study.

The post-education test was first administered immediately after the education session and again after the nurses had been using the RADAR tool for approximately 3 months.

Measurement

The pre- and post-education tests consisted of 15 questions developed by the John A. Hartford Foundation of Geriatric Nursing Excellence at the University of Iowa College of Nursing.15 The demographic questionnaire addressed age, gender, licensure (registered or licensed practical nurse), nurse experience, experience caring for older adults, employment status (part-time, full-time, or PRN), and nursing education (diploma, associate degree, bachelor’s degree, or master’s degree).

Two months after the education sessions, the principal investigator established interrater reliability of the bedside nurses by conducting concurrent screening of patients.

At the end of the project, nurses completed a 5-item dichotomous perception questionnaire. This was the same questionnaire used by Voyer er al in their RADAR validation study.12

Analysis Plan

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 22) was used to analyze the data. Participants were excluded if the nurse did not complete either of the post-education tests or if answers were missing on any of the tests. A repeated measures ANOVA was used to analyze the pre-education and 2 post-education test scores. A t test was used to analyze the pre-education test and first post-education test. Interrater reliability data was analyzed using Cohen’s Kappa.

Article continues below Figure

Results

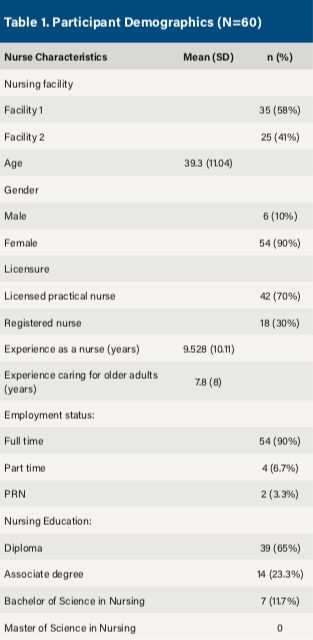

Eighty-three nurses attended the education sessions (Figure 1). Of the eligible 83 nurses, 60 agreed to participate in the study (35 from one facility and 25 from the other), 36 completed the final post-education test, and 35 completed the perception questionnaire. Participant demographics are reported in Table 1.

To evaluate for delirium knowledge improvement, a paired t test and repeated measures ANOVA were conducted on test scores. The paired t test (2 tailed) of the scores for the pre-education test and first post-education test demonstrated nurses gained an average 3.45 points (95% CI, 2.73, 4.17) after education (n=56). A significant increase in knowledge was apparent when the 2 test scores were compared (P<.05).

The difference between scores on the pre-education test and 2 post-education tests were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA (n=36). The repeated measures ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction determined that differences in pre-education and post-education mean test scores were statistically significant (F[1.80, 57.67]=24.64, P<.05). Post-hoc pairwise tests were used to compare scores. The Bonferroni test revealed that education increased delirium knowledge scores immediately afterward and 3 months following the education session (P<.05), but there was not a statistically significant difference in scores between the first and second post-education test (12.06+2.150 vs 11.42+2.180, P=.52). In summary, delirium education improved delirium knowledge both immediately after the education and 3 months after the education, but there was not significant evidence of change between the 2 post-education tests.

To evaluate for correlation between the nurses’ and the principal investigator’s RADAR test scores, Cohen’s kappa was conducted to analyze interrater reliability. The result of this analysis was a kappa of 0.634, indicating a significant level of correlation between RADAR scores of bedside nurses and the principle investigator. This suggests that the measurement process was consistent between the nurses and the principle investigator. The significance level of the kappa was determined based on a commonly cited scale with 6 levels of agreement, with 0.61-0.80 being the fifth highest level.16

The final questionnaire evaluated nurse perception of the RADAR tool and was completed at the same time as the final post-education test. Responses revealed that 80% to 91.4% of the nurses “agreed” with the 5 questions (Table 2). This indicates an overall positive perception of the RADAR tool.

Discussion

This study found nurse knowledge of delirium in SNFs improved through a focused delirium education session. Test scores improved immediately after the education session and 3 months afterward, suggesting knowledge was maintained. This study was developed and evaluated with concepts considered important to improving recognition of delirium: support for the program from both administration and users, effective clinical leadership, a sense of ownership among nursing staff, and practical hands-on training for staff.7 A specific component that proved beneficial was ongoing support and education from the principle investigator throughout the study period.

The issue of delirium underrecognition in the SNF setting is well established, but a gap exists in the literature on how to improve knowledge among bedside nurses. Without an understanding of delirium, bedside nurses cannot adequately assess for it. Further studies are needed to evaluate the impact, if any, of the improved knowledge on delirium recognition in the SNF setting. In addition, further studies are needed to evaluate whether the one-third to two-third percentage of underrecognition identified by Marcantonio et al can be reduced through improvement in bedside nurse knowledge of delirium.5

Additionally, this study evaluated whether nurses who received education on RADAR administered the tool correctly compared with the gerontological advanced practice nurse. The findings suggest that the RADAR tool was administered accurately in the 2 SNFs in which it was tested. While the tool has been validated in Canada, it had not been used in the United States prior to this study. During the education session, the nurses watched a video with case vignettes that explained how to administer the tool, and this likely contributed to their ability to administer the tool reliably.14 While this pilot study used convenience sampling for assessments, it does establish that nurses at these facilities were accurately screening for delirium based on interrater assessments.

Finally, this study also evaluated nurse perception of the RADAR tool using the same questions nurses were asked in the RADAR validation study.12 Both studies found nurses had a positive perception of the RADAR. Table 2 lists specific questions asked and nurse responses from this study and from the Voyer et al study.12 Responses suggest the education session provided the necessary knowledge for nurses to feel confident using the RADAR tool to assess for delirium and that the suggested method of observing patients during medication administration was appropriate. These findings suggest that it is feasible for SNF nurses to use the RADAR tool for routine delirium screening of all patients they care for on each shift.

As noted in the last item of the questionnaire in Table 2, 20% of the nurses in this study felt the RADAR was a time burden, while only 4% of nurses in the RADAR validation study had such a response.12 The RADAR validation study found that RADAR in the paper form took just 7 seconds, while answering questions in the EMR in this study took approximately 15 seconds.12 The difference could also be attributed to our implementation of the RADAR tool on all patients, while nurses in the RADAR validation study administered the RADAR tool to patients enrolled in the study and not their entire patient load.12

Establishing the feasibility of using the RADAR tool in 2 SNFs in the United States has significant implications for future practice. Prior to this study, the RADAR tool had not been incorporated into a facility-wide implementation to screen for delirium in all patients on each shift.12 In addition, the tool had not been implemented into an EMR so as to be integrated into usual care routines.

Limitations in this study involve its size and scope. The study was modeled after a large validation study but was in no way a replication of that study.12 This pilot study evaluated only 2 SNFs. Evaluation was limited to pre-education and post-education test scores and interrater reliability assessments. The interrater reliability checks, while helpful, were not randomized. Also, the study did not evaluate nurse action following positive assessments.

Further studies are necessary to investigate nurse action following positive RADAR assessments and whether use of the RADAR tool increases notification to providers. In addition, it would be important to determine if earlier identification of delirium occurs in facilities using the RADAR tool. Protocols need to be developed and evaluated on the comprehensive management of delirium in the postacute care setting. The protocols should be multifactorial, focusing on prevention, early recognition, and treatment.

Conclusion

With the established feasibility of this study, future work can be done to further evaluate use of the RADAR tool. Various tools have been developed for the screening of delirium, but the ease of use with RADAR makes it especially useful in the SNF setting. Further evaluation needs to identify the impact of the tool on the care of patients with delirium in the SNF setting.

References

1. Voyer P, Richard S, McCusker J, et al. Detection of delirium and its symptoms by nurses working in a long term care facility. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(3):264-271.

2. Arinzon Z, Peisakh A, Schrire S, Berner YN. Delirium in long-term care setting: indicator to severe morbidity. Arch Geront Geriatri. 2011;52(3):270-275.

3. Kiely D, Marcantonio ER, Inouye SK, et al. Persistent delirium predicts greater mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(1):55-61.

4. Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, Leo-Summers L, Inouye SK. One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):27-32.

5. Marcantonio ER, Kiely DK, Simon SE, et al. Outcomes of older people admitted to postacute facilities with delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(6):963-969.

6. Voyer P, Richard S, Doucet L, Danjou C, Carmichael PH. Detection of delirium by nurses among long-term care residents with dementia. BMC Nurs. 2008;7(1):4.

7. Voyer P, McCusker J, Cole MG, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a delirium prevention program for cognitively impaired long term care residents: a participatory approach. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(1):77.e1-9.

8. Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg EJ, Inouye SK. The Confusion Assessment Method: a systematic review of current usage. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):823-830.

9. Schuurmans MJ, Deschamps PI, Markham SW, Shortridge-Baggett LM, Duursma SA. The measurement of delirium: review of scales. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2003;17(3):207-224.

10. Wong CL, Holroyd-Leduc J, Simel DL, Straus SE. Does this patient have delirium?: value of bedside instruments. JAMA. 2010;304(7):779-786.

11. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med.1990;113(12):941-948.

12. Voyer P, Champoux N, Desrosiers J, et al. Recognizing acute delirium as part of your routine [RADAR]: a validation study. BMC Nursing. 2015;14:19.

13. American Psychiatry Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

14. Voyer P. RADAR training video. https://radar.fsi.ulaval.ca/?page_id=54. Accessed November 28, 2018.

15. The John A. Hartford Foundation Center of Geriatric Nursing Excellence. Delirium Knowledge Assessment Test. 2nd ed. Iowa City, Iowa: The University of Iowa College of Nursing; 2009.

16. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):59-174.