Creating Safer Environments for Long-Term Care Staff and Residents

Long-term care (LTC) facilities face many challenges to providing ongoing high-quality care while maintaining an economically efficient operation. A major contributor to these challenges is workplace injuries to staff. The healthcare industry continues to be one of the worst performers in protecting workers from sustaining occupational injuries. A review of trends related to occupational injury experience reported by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics showed that annual injury rates at LTC facilities are consistently much higher than for all private industries and other healthcare fields.1 According to the National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI), the private industry had a rate of 3.6 injuries per 100 full time employees (FTE) in 2009, whereas LTC facilities reported a rate of 8.4 injuries per 100 FTE that same year.2 Injuries result in direct and indirect costs. Direct cost is defined as the compensation paid to the injured worker plus the medical costs required to treat the injury. Indirect costs include items such as cost to replace the injured worker, administrative time, training time, reduced productivity on the unit, and other operational expenses. In the healthcare industry, inflation-adjusted direct and indirect costs associated with back injuries—the most significant occupational injury problem for most healthcare organizations—were estimated to be $7.4 billion annually in 2008.3

Most back injuries in caregivers are related to resident handling tasks. In fact, back strains and sprains account for more than 60% of the direct costs associated with occupational work injuries.4-9 Although many organizations have attempted to control this problem, its persistance in facilities has been well documented.4-12

The pain and suffering to direct-care staff, in addition to the workers’ compensation costs associated with these injuries, are significant burdens on a facility’s resources. In light of shortages of direct-care staff, an aging workforce, and high turnover rates, the loss of valuable skilled workers through work-related injuries can create an additional crisis for healthcare organizations.

Learning From Evidence-Based Practice

A comprehensive report generated by the NCCI, done in cooperation with the University of Maryland School of Medicine, indicated that an increased emphasis on safe lifting programs at LTC facilities is associated with fewer workplace injuries and lower workers’ compensation costs.2 These findings were based on statistical analysis and considered ownership structures and differences among workers’ compensation system across states. The study also identified the key components of an effective and safe resident-handling program, which included powered lifting equipment, policies and procedures, training, compliance with the policies and procedures, and direction from senior leadership, such as the director of nursing.

Findings summarized in an article by the Patient Safety Center of Inquiry in Tampa, FL, which reviewed current evidence for effective interventions designed to reduce caregiver injuries, provide further insight into the key elements of effective and safe patient-handling programs.13 These findings indicate a growing body of evidence that shows newer interventions are effective or show promise in reducing musculoskeletal pain and injuries in caregivers. The article states that a major paradigm shift is needed to improve workers’ safety, which can be accomplished by implementing the following evidence-based practices: (1) using patient-handling equipment and devices; (2) following patient care ergonomic assessment protocols; (3) establishing no-lift policies; and (4) training staff on the proper use of patient-handling equipment and devices.

A well-researched publication issued by the US Department of Health and Human Services showed that safe lifting programs can reduce resident-handling workers’ compensation injury rates by 61%, lost workday injury rates by 66%, and restricted workdays by 38%.14 It also showed that these programs can reduce the number of workers suffering from repeated injuries, but a percentage for this data was not provided.

Promising new interventions that are still being tested include establishment of unit-based peer leaders and use of clinical tools, such as algorithms and patient assessment protocols. Given the complexity of this high-risk, high-volume, high-cost problem, multifaceted programs are more likely to be effective than any single intervention.

Translating the Evidence Into Practice: The CASE Program

Many organizations want to address the impact and burden of healthcare worker occupational injuries, but they often spend more time reacting to these injuries than preventing them because of limited resources. A simple and cost-effective method to address safe patient handling that is also sustainable over time, called “Creating a Safer Environment,” or “CASE,” is one set of solution strategies. The program focuses on creating an organizational culture of safety that staff can integrate into everyday operations with the aim of preventing accidents, controlling losses, improving the quality of work life for staff, and improving the quality of care for residents.

Leadership, Technology, and Training

As with any program within a facility, someone must take a leadership role to champion the program and work within a supportive team. The champion and support team of the CASE program oversee and monitor program activities. The objectives of the program should align closely with the normal job responsibilities of the team members. Doing so empowers the team members to view program responsibilities not as a burden, but as a tool or mechanism to help them become more effective in their usual job responsibilities. The team then identifies other key direct-care workers who can serve as a peer-to-peer resource for the caregivers on all shifts and help address questions and issues as the program rolls out.

Safe resident lifting requires technology to minimize and eliminate manually lifting and moving residents, and a process to integrate these new methods into the operational activities of daily care delivery. The CASE program provides a method, described later in this article, for reviewing the existing dependency classification profile of the resident population to estimate equipment needs. This estimate is adjusted and refined with input from facility staff. Identified equipment needs might include mechanical lifting devices, lifting aid devices, and proper furnishings matched to particular resident needs.

Education and training are important to the success of this process, so that new equipment is used effectively. Everyone at the facility must recognize that improperly lifting and moving residents while providing care and assisting with mobility can result in worker injury and that specific changes will need to be made to prevent such injuries. All caregivers must “buy in” to new methods for lifting and transferring residents. Involving direct-care workers early in the process makes it easier to establish their support and overcome resistance to change. The program has a simple interactive activity, which has been successfully used by many caregiver groups. Through this interactive activity, caregivers work together to identify the high-risk resident handling activities in their units. Support, or buy-in, is important not only for the caregivers, but also for administration and senior leadership, who are accountable for justifying the costs of new equipment. Everyone needs to understand how an effective safe lifting program can produce a quick return on time and financial investments.

Policies, Procedures, and Resident Assessments

A consistent vision of the program by all staff is achieved through creating new policies and procedures; the policy states the position of the organization, and the procedures provide the guidance and methods necessary to achieve what is written in the policy statement. In the CASE program, an organization’s training needs are assessed by leadership and the support team, and then a training plan is developed with the facility inservice education staff for initial roll out. As the plan is developed, it is important to ensure that effective training continues over time. This includes “train-the-trainer” strategies, by which key individual caregivers are given extra training to provide them with a high level of knowledge and understanding about the equipment. This group of expert users sustains the program by serving as a resource to other staff members.

Normally all facilities regularly assess residents’ level of mobility; thus, assessment of residents for the CASE program does not burden the staff with extra work. These typical assessments are expressed in classifications set forth in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Resident Assessment System, Section G, titled Physical Functioning and Structural Problems. By using the dependency classification and specific condition, each resident’s lift and transfer needs can be determined and integrated into existing care plans. Through this assessment process, equipment requirements are identified specific to a particular resident and solutions are matched to the lift and transfer problems associated with that resident. This information must then effectively be communicated to all caregivers who are involved in the resident’s care. Through this approach, risks to caregivers and residents are minimized.

Our Pilot Study

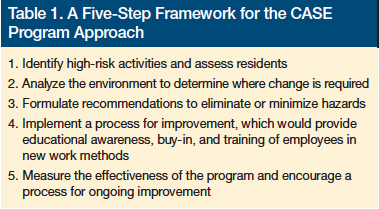

The CASE approach is designed to be easily implemented. With a little initial training and practice, simple tools can become an integral part of delivering daily care. Table 1 summarizes the approach. The CASE approach is designed to be implemented with the facility’s internal resources and does not require ongoing expensive consultation; however, if a facility needs ongoing support, many vendors are available to provide it.

To test the concepts of this program in a real-world setting and to better understand the process of implementation, a pilot study project was undertaken. Selection of the pilot study site was done in cooperation with the Atlantic Charter Insurance Company, which provides workers’ compensation coverage to many LTC facilities in Massachusetts and New Hampshire. The site selected for the pilot study was Radius Mayflower, located in Plymouth, MA. Radius Mayflower is part of Radius Management Services, which runs approximately 20 LTC facilities in Massachusetts. To begin the pilot study process, a presentation was made to the corporate director of operations for Radius, the administrator at the study site, and key staff members from the facility. Consistent with the CASE program philosophy, it was necessary to establish buy-in and commitment from senior leadership before the project began.

Selecting a High-Risk Unit to Improve

The Allerton unit at Radius Mayflower was selected as the study unit because its resident population had a high level of dependency, presenting a high level of risk to staff. In addition, the unit’s staff had experienced a high number of occupational injuries resulting in many lost workdays.

The normal population on the Allerton unit consisted of 57 residents who were, for the most part, severely cognitively and physically impaired. Some did have limited weight-bearing ability, but almost all of the residents were totally dependent. Applying the site assessment methodology of the program to establish equipment needs, it was determined that four full sling lifts and one stand-assist lift would be required for the resident lifting and handling needs on the unit. The Eaton unit, at the same facility, had a similar resident population and was selected as the control unit.

Continued on next page

Implementing the Program

Implementing a safe lifting program on the Allerton unit presented several challenges. The resident population, all considered to have special needs, had physical impairments requiring them to wear specialized orthotics and body jackets. The residents were totally dependent on staff for all activities of daily living, including positioning and transfers. The staff caring for these individuals was routinely required to perform many lifting tasks, yet they were initially resistant to the idea of using resident lifting equipment.

To launch the program on the unit, education and training sessions were scheduled. At the initial education program, the concepts of safe lifting were presented to the staff, and a vendor representative demonstrated the new lifting equipment. Afterward, a training schedule was set up and the same vendor representative trained key staff members, who would in turn train other staff.

Results

The implementation of the program had positive results on staff attitudes, as measured by a survey before and after the CASE interventions (Table 2), by the emerging acceptance of the participating staff, and by a reduction in staff injuries. To measure the benefits beyond injury reduction, a preintervention survey was conducted with 24 caregivers, including registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, aides, and other staff members from the Allerton unit. Attitude statements were presented to measure aspects of staff satisfaction and their opinions of the program. The survey tool was administered before the intervention and again approximately 3 months after implementation. The survey asked staff members to respond to statements using a 7-point rating scale (1=strongly disagree to 7=strongly agree). The survey had a 100% response rate.

When asked if they enjoyed coming to work, postintervention scores increased from 4 (neither agree nor disagree) to 6 (moderately agree). Staff also felt that the program had a positive impact on morale. The preintervention average score indicated that staff slightly disagreed that morale was “better today than it was a year ago,” whereas postintervention they agreed slightly to moderately that morale was “better today than it was a year ago.” Staff also felt that management and supervision were more concerned with their individual safety. Preintervention, staff slightly agreed that management was committed to providing a safe environment, and postintervention, they moderately to strongly agreed that management was committed to providing a safe environment. Preintervention, the staff only slightly agreed that supervisors in their work group were concerned with their safety. Postintervention, they strongly agreed with this statement.

An indication that the methods to lift and transfer dependent residents with new equipment had a positive impact regarding staff attitudes is also reflected in responses to the question, “Residents should be lifted with the mechanical lifting equipment, not manually.” Preintervention, the staff moderately disagreed with this statement, whereas postintervention, they strongly agreed with it. To further reinforce the need to redirect training efforts in LTC, staff attitudes regarding the amount of training provided remained the same before and after the intervention. Preintervention training had involved body mechanics and teaching of proper manual lifting techniques, whereas postintervention training was focused on how to effectively integrate the new lifting equipment into the process of delivering care. Through postintervention training, new and better methods to lift and transfer residents were being taught and implemented as part of the ongoing revision of the training protocols, and time for training was not increased.

As staff became familiar with using new equipment, they learned that use of the lifts did not increase time and actually facilitated lifting and transferring patients. In addition, the use of lifts helped with other activities, such as weighing residents. Using lifts with a built-in weight scale eliminated many manual lifting tasks and simplified the process. Staff also observed that residents felt safer and more secure when being transferred with lifts as observed by smiles, facial expressions of pleasure, and a decrease in rigidity in the residents’ bodies as they were being transferred with lifts. The application of properly chosen slings created a cuddling effect for the residents, which made them feel more comfortable and less anxious during the transfer process.

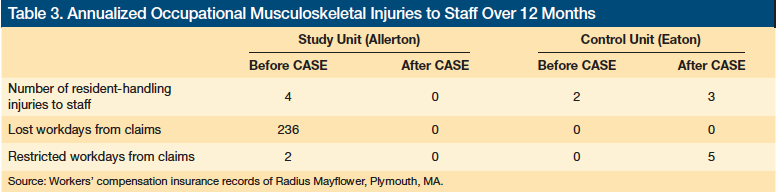

Beyond improvements to the environment of care, impressive results were demonstrated related to occupational injury experience. A review of the injury experience on the Allerton unit showed that there were four resident handling incidents resulting in 236 lost workdays and 2 restricted workdays before the intervention. Postintervention, there were no reported resident handling injuries to staff over a 12-month period. For the control unit, the injury experience remained close to the same for the preintervention and postintervention periods. Injury experience results are displayed in Table 3.

The five-step method described in Table 1 provides for ongoing cycles of continuous improvement. Once a facility has completed its monitoring and evaluation in step five, it moves back to step one and completes a risk assessment of the current situation, striving for continued improvement by reapplying the five-step process. The timeframe is determined by each individual facility to best fit its situation and resources.

Conclusion

The results of our pilot study are consistent with the evidence-based practice of safe patient handling, demonstrating that occupational injuries can be reduced in a systematic manner. The study also illustrates the key elements for an effective and safe resident-handling program, which includes engaging the commitment of company operations management and senior leadership and involving direct-care staff early in the process to create buy-in. The program was implemented without adding any staff. The facility used internal resources with some outside expert support to help get started. The important outcome is that the program was implemented and has been sustained with internal resources. The ideas presented in this article can help create and maintain effective safe patient-handling programs in LTC facilities as well as in other healthcare settings.

The author reports no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Industry Injury and Illness Data 2010. www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/osh_10202011.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2012.

2. Restrepo T, Schmid F, Shuford H, Shyong C. Safe lifting programs at long-term care facilities and their impact on workers’ compensation costs. NCCI Research Brief. https://www.ncci.com/documents/LTC_2011_Research_Brief.pdf. Published March 2011. Accessed December 21, 2011.

3. American Nurses Association. Background on Safe Patient Handling. www.anasafepatienthandling.org/Main-Menu/SPH-Background/Background.aspx. 2011. Accessed December 21, 2011.

4. Engkvist I, Hagberg M, Lindén A, Malker B. Over-exertion back accidents among nurses’ aides in Sweden. Saf Sci. 1992;15(2):97-108.

5. Harber P, Billet E, Gutowski M, SooHoo K, Lew M, Roman A. Occupational low-back pain in hospital nurses. J Occup Med. 1985:27(7):518-524.

6. Hedge A, Subach BR. Back care for nurses. www.spineuniverse.com/wellness/ergonomics/back-care-nurses. 2011. Accessed December 21, 2011.

7. Hignett S. Work-related back pain in nurses. J Adv Nurs. 1996;23(6):1238-1246.

8. Jensen R. Disabling back injuries among nursing personnel: research needs and justification. Res Nurs Health. 1987;10(1):29-38.

9. Khuder S, Schaub EA, Bisesi MS, Krabill ZT. Injuries and illnesses among hospital workers in Ohio: a study of workers’ compensation claims from 1993 to 1996. J Occup Environ Med. 1999;41(1):53-59.

10. Ljungberg AS, Kilbom A, Hägg GM. Occupational lifting by nursing and warehouse workers. Ergonomics. 1989;32(1):59-78.

11. Nelson A, Fragala G, Menzel N. Myths and facts about back injuries in nursing. Am J Nurs. 2003;103(2):32-40.

12. Pheasant S, Stubbs D. Back pain in nurses: epidemiology and risk assessment. Appl Ergon. 1992;23(4):226-232.

13. Nelson A, Baptiste AS. Evidence-based practices for safe patient handling and movement. Orthop Nurs. 2006;25(6):366-379.

14. Collins J, Nelson A, Sublet V. Safe lifting and movement of nursing home residents. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Website. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2006-117. www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2006-117/pdfs/2006-117.pdf. Published February 2006. Accessed December 21, 2011.