Community Long-Term Care and the Alzheimer’s Disease Patient Navigator

The need to provide long-term care (LTC) in a more cost-effective manner includes avoiding—or at least delaying—nursing home placement as long as possible. One way to accomplish this is through the use of non-traditional LTC team members such as patient navigators. Patient navigators have proven capable of both improving health outcomes and decreasing costs to the health care system. Although the use of patient navigation has been described mostly in the context of cancer care, there are opportunities to apply the same valuable principles of patient navigation beyond oncology to disease states such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

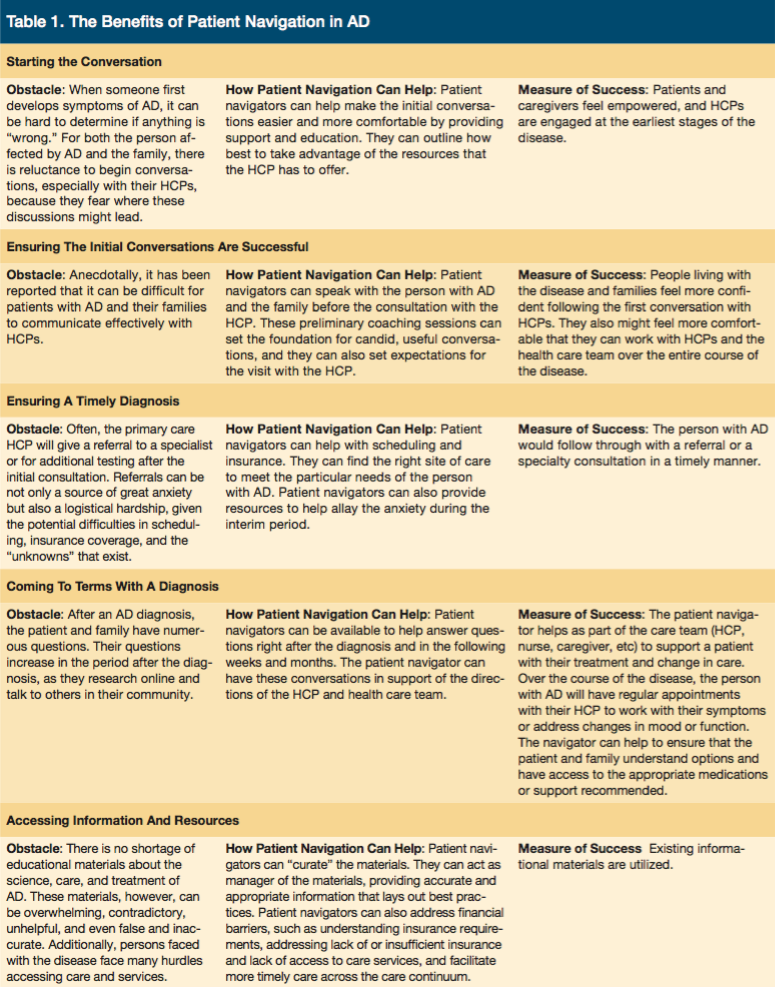

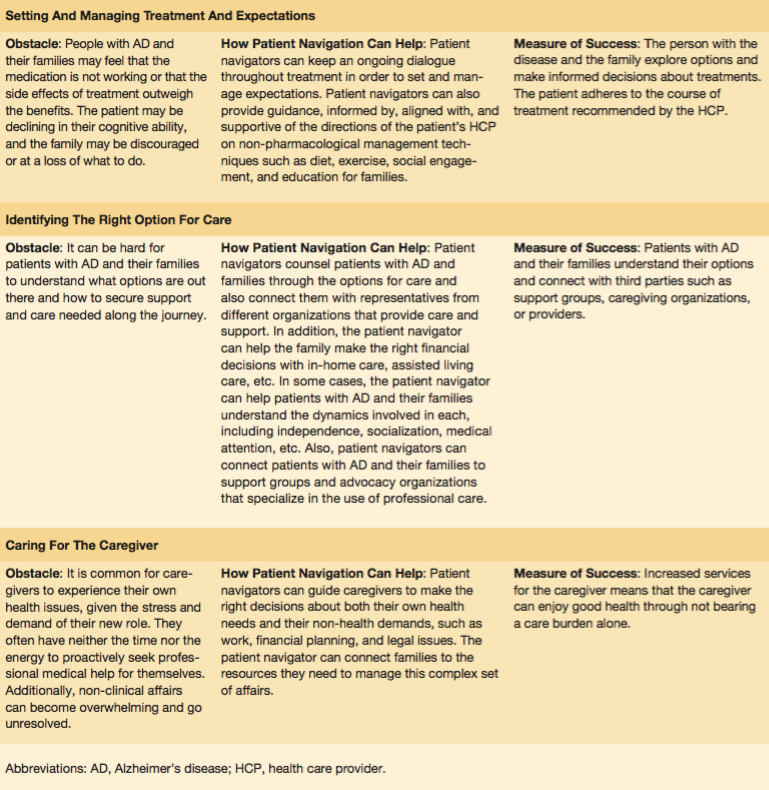

There are many frail older adults with AD living in the community with limited, if any, caregiver support. Historically, the answer for these individuals had been relocation to a nursing home setting. However, in today’s environment of total cost of care control, the cost associated with skilled nursing facility care is an easy target for cost reduction. As a result, new resources are emerging to provide the needed care to maintain these patients safely in the community through supportive services and, more importantly, through early diagnosis and treatment. These functions can be best served through the role of the patient navigator for AD (Table 1).

The patient navigation movement started more than 15 years ago, when the President’s Cancer Panel submitted to President George W Bush a report entitled “Voices of a Broken System: Real People, Real Problems.”1 In this report, the authors asserted that, despite “profound advances” in cancer research: “[O]ur health care delivery system is broken. It is the root of vast and unnecessary suffering, personal financial ruin, and loss of dignity for millions of people with cancer, who must fight their way into and through a dysfunctional system even as they struggle to save their very lives.”1

Though cancer and AD are very different diseases—and though there are vastly different levels of medical solutions to the two diseases—the barriers to treatment and complexity of care have much in common. In both disease states, costs and financial implications of care are a major concern; the logistical challenges with appointments, follow-ups, and prescription adherence are many; and learning to manage the caregiving burden is a profound challenge.

Given these shared obstacles, the benefits of patient navigation in oncology will easily translate to similar benefits of patient navigation in AD. For one, patient navigators operate across the entire continuum of care. From early prevention to post-diagnosis, this broader view of care will prove valuable for those with AD, for which stigma and doubt can prevent proactive measures and complex systems can slow care. For another, the patient navigation model has proven to be adaptable across diseases and patient populations. Because disease progression substantially impacts care needs for AD, this adaptability will be critical. Finally, patient navigation is efficient and scalable. Patient navigators can be placed into the field quickly, requiring neither substantial changes to the medical system nor years of training for the navigators. Training programs for navigators can be expedient, cost-effective, and results-oriented.

As in cancer care, patient outcomes in AD depend on far more than just medical treatment. Care needs to be provided beyond the patient and medications to include caregivers and other non-medication factors. By developing and implementing patient navigation for AD, improved outcomes can be achieved.

1. National Institute of Health, National Cancer Institute. Voices of a Broken System: Real People, Real Problems. President’s Cancer Panel: Report of the Chairman 2000-2001. http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/archive/pcp00-01rpt/PCPvideo/voices_files/PDFfiles/PCPbook.pdf. Published September 2001. Accessed May 9, 2016.