Cimetidine Treatment of Sexually Inappropriate Behavior in Dementia: A Case Report and Literature Review

Sexual disinhibition is recognized as one of the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and occurs in up to 25% of dementia patients. It is extremely disruptive to both the family and the caregivers of the patient. Several classes of drug have been used to control these behaviors, but all of these treatments have accompanying risks. The authors report a case of an elderly patient with dementia who exhibited inappropriate sexual behavior. This patient responded positively to treatment with the nonhormonal anti-androgen cimetidine. Patients with dementia who are given such treatments must be carefully evaluated for response and tolerability.

Key words: Dementia, inappropriate sexual behavior, pharmacological treatment, cimetidine.

Abstract: Sexual disinhibition is recognized as one of the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and occurs in up to 25% of dementia patients. It is extremely disruptive to both the family and the caregivers of the patient. Several classes of drug have been used to control these behaviors, but all of these treatments have accompanying risks. The authors report a case of an elderly patient with dementia who exhibited inappropriate sexual behavior. This patient responded positively to treatment with the nonhormonal anti-androgen cimetidine. Patients with dementia who are given such treatments must be carefully evaluated for response and tolerability.

Key words: Dementia, inappropriate sexual behavior, pharmacological treatment, cimetidine.

Citation: Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging. 2015;23(6):39-42.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Behavioral disturbances are common in dementia and occur in about 60–70% of dementia patients.1 The prevalence of inappropriate sexual behaviors among dementia patients varies from 1.8% to 25%,2 and men are more likely than women to exhibit inappropriate sexual behaviors in dementia.3 Though it is not common, inappropriate sexual behavior is extremely disruptive to family members and care providers in healthcare facilities.4

A recent study5 divided improper sexual behaviors into two types: (1) intimacy-seeking, or normal behaviors that are misplaced in social context (kissing, hugging); and (2) disinhibited, or rude and intrusive behaviors that would be considered inappropriate in most contexts (lewdness, fondling, and exhibitionism). Sexual disinhibition is recognized as one of the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD).6

Behavior in dementia may be misinterpreted as sexual in nature when, in fact, it may have an entirely different meaning to the resident.7 The patient with dementia may not be acting on sexual thoughts as much as expressing a desire for intimacy or reassurance, or may not be aware of his or her surroundings and display behavior considered normal in private but not public, such as masturbation.8 Thus, a thorough assessment of the behavior should be undertaken before diagnosing it.

Pharmacological Treatments

A UK national survey of prescribing patterns for psychotic and behavioral symptoms in dementia was published in 2002.9 For “sexual disinhibition,” the preferred categories were classical and atypical antipsychotics. The most common individual treatment choices were haloperidol (15%), thioridazine (11%), and risperidone (10%).

There have been no randomized controlled trials to assess the pharmacological efficacy of any drug for reducing inappropriate sexual behaviors in patients with dementia, but several psychotropics have been tried with variable effects. Case reports have been published in which the antipsychotic medications haloperidol,10 zuclopenthixol,11 olanzapine,12 quetiapine,13,14 and aripiprazole15 have been found useful. The benefits of using antipsychotics in patients with dementia must be weighed against the potentially dangerous side effects of these drugs, however. The typical antipsychotics are associated with extrapyramidal side effects, and all antipsychotics as a class increase the incidence of sudden death and cerebrovascular events (ie, stroke). Many psychiatrists will try selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as the first-line drug. SSRIs can cause sexual dysfunction as a side effect and may offer additional benefits for other behavioral symptoms.16 The antidepressants paroxetine,17 citalopram,18,19 clomipramine,20 and fluoxetine21 also have been used, with citalopram being the most commonly prescribed of these drugs. These antidepressants were found to be effective, via a proposed mechanism of increased serotonin leading to anti-libidinal and anti-obsessional effects. The anticonvulsant drugs carbamazapine22 and gabapentine23-25, which are the only two anticonvulsants reportedly used for this purpose, have also had favorable reports.

In addition to psychotropic medications, a few other pharmaceutical approaches for the treatment of inappropriate sexual behavior in patients with dementia have been reported. There is one case report of the use of pindolol,26 a beta blocker, to reduce inappropriate sexual behavior. Pindolol was found to completely eliminate this behavior in 2 weeks. Treatment with hormones, including medroxyprogesterone acetate,27-30 cyproterone acetate,31,32 diethylstilbestrol,33 and the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist luprolide,34 as well as with nonhormonal anti-androgens, including cimetidine,35 ketoconazole,35 spironolactone,35 and finasteride,36 has also been attempted. In a case series of 20 patients with dementia and inappropriate sexual behavior, Wiseman et al35 reported a good response to cimetidine alone or in combination with spironolactone and/or ketoconazole. Cimetidine is a CYP450 enzyme inhibitor that interacts with several drugs; the potential for drug–drug interactions should be kept in mind, especially in light of the polypharmacy that is common in elderly dementia patients. Spironolactone has the potential of causing hyperkalemia; therefore, patients being treated with this drug require regular monitoring. Of anticholinesterases that have been used, rivastigmine37 is the only one that has shown any benefit. Donepezil, another anticholinesterase, has been shown to increase libido and compulsive sexual thoughts.38

Case Report

An 85-year-old man of Afro-Caribbean origin who was diagnosed with vascular dementia in 2010 was referred to the Community Mental Health team with memory problems and an inability to live alone safely. He had lived alone in a one-bedroom apartment after his wife passed away in 2009. Following her death, he started smoking and drinking alcohol heavily. He had an unsteady gait with a stooped posture and was noted to have several cuts and bruises, which were likely the result of falls secondary to alcohol intoxication. He had no insight into his memory difficulties or the problems he had with independent living. It was difficult to do a mini-mental state examination (MMSE) due to his hearing impairment, but he appeared to be moderately cognitively impaired. A computerized tomography (CT) head scan showed involutional changes, previous left parietal infarct, and widespread small vessel ischemic changes.

In September 2011, he started becoming aggressive. He was not on treatment for any medical condition. Soon after, he was found wandering in the cold and was taken to the emergency department of a hospital and treated for hypothermia. He had not been known to the psychiatric services before then. Following admission, he was placed in a long-term care (LTC) home in December 2012.

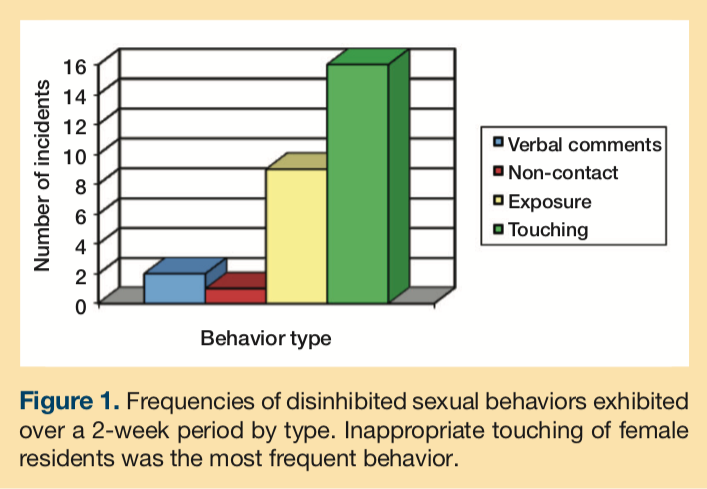

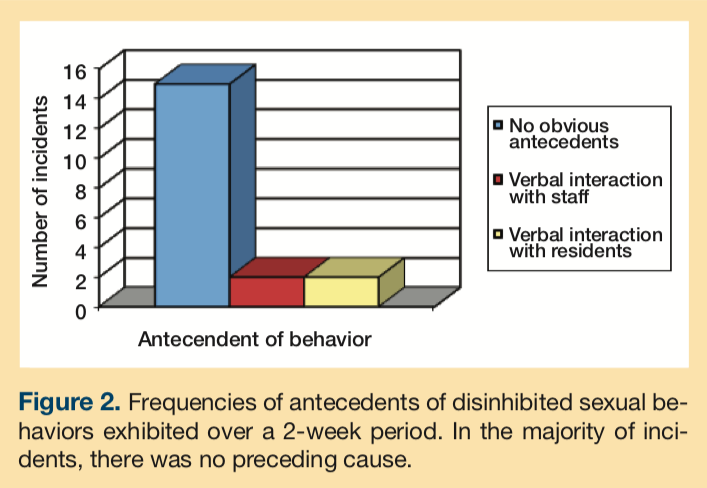

In February 2013, he presented with sexually disinhibited behavior towards females in the care home. The frequencies of different types of disinhibited sexual behaviors exhibited by the patient are shown in Figure 1. These behaviors included inappropriately touching other patients, including disrobing them and removing their incontinence pads; approaching females (both staff and residents) and asking for sex; and masturbating in front of female residents and staff members. These behaviors occurred 3–4 times per week. Inappropriate sexual behaviors were recorded using the St. Andrew’s Sexual Behavior Assessment (SASBA) scale.39 The patient did not exhibit any physical aggression. The inappropriate behaviors were most evident during early and late afternoon and were displayed when he was not engaged any meaningful activities. They were sometimes preceded by verbal interactions with the staff and other patients (Figure 2). The staff responded by ignoring the behavior in 8% of incidents, talking to the patient about the inappropriateness in 52% of incidents, and removing him to his room in 39% of incidents.

He was started on memantine, which was titrated to the maximum dose of 20 mg, for control of inappropriate sexual behavior. Memantine had no effect, so 400 mg of cimetidine was started. Cimetidine was chosen for this patient because he was not on any other medication, ruling out the possibility of drug–drug interactions. There was no evidence of depression or psychosis. A blood test revealed hepatic and renal functioning to be reasonably good.

In the next 3 weeks, there was a significant reduction in the sexually inappropriate behavior. There were no incidences of asking for sex or touching female staff or residents inappropriately. On follow-up during the next 6 weeks, there were two instances of him entering the bedroom of elderly female residents and trying to have sexual intercourse with them. Cimetidine was increased to 800 mg, and, over the next 4 weeks of monitoring, there were no incidents of inappropriate sexual behavior. Cimetidine was well tolerated with no side effects.

Discussion

Cimetidine is a H2 receptor antagonist and also has anti-androgen effects. It blocks the androgen receptor in the pituitary or the hypothalamus,40 reducing sexual desire in individuals of both sexes and affecting arousal and orgasm. Cimetidine also demonstrated nonsteroidal anti-androgen effects in rats.41

Cimetidine inhibits hepatic cytochrome enzymes CYP1A2, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4, and interacts with a large number of concomitantly prescribed drugs. Cimetidine was in the original Beers List, which is a resource for healthcare providers to assist in improving medication safety in older adults, as a potential medication to avoid in older patients. Recently, however, cimetidine was dropped from this “drugs to avoid” list42 because the potential for drug interactions with these medications are not unique to the elderly. It has been reported in the literature that cimetidine can cause confusion, psychomotor restlessness, hallucinations, disorientation, stupor, and coma. Predisposing factors for these side effects include advanced age, hepatic or renal dysfunction, or severe underlying disease.43 The patient’s mental state should be closely monitored for the listed side effects and thier detection should prompt a reduction or stopping of cimetidine.

Conclusion

Several psychotropics and other drugs have been used for the management of inappropriate sexual behavior in patients with dementia. Antipsychotics may have a modest benefit, but the risks associated with these medications are significant. There have been previous case reports of sexually inappropriate behavior responding positively to nonhormonal anti-androgens, and our case report adds to this literature. Cimetidine in the doses used to treat our patient is usually well tolerated. Given the difficulty faced in managing patients with dementia who develop inappropriate sexual behavior, the use of nonhormonal anti-androgens such as cimetidine should be considered for response and tolerability.

References

1. Geldmacher DS. Contemporary Diagnosis and Management of Alzheimer’s Dementia. Newtown, PA: Handbooks in Health Care Company; 2003.

2. Tucker I. Management of inappropriate sexual behaviours in dementia: a literature review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(5):683-692.

3. Holmes D, Reingold J, Teresi J. Sexual expression and dementia. Views of caregivers: A pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12(7):695-701.

4. Light SA, Holroyd S. The use of medroxyprogesterone acetate for the treatment of sexually inappropriate behaviour in patients with dementia. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006;31(2):132-134.

5. de Medeiros K, Rosenberg PB, Baker AS, Onyike CU. Improper sexual behaviours in elders with dementia living in residential care. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26(4):370-377.

6. Bird M, Moniz-Cook E. Chapter 33: Challenging Behaviour in Dementia: A Psychosocial Approach to Intervention. In: B Woods, L Clare, eds. Handbook of the Clinical Psychology of Ageing, 2nd Edition. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2008:571-594.

7. Kuhn DR, Greiner D, Arseneau L. Addressing hypersexuality in Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol Nurs. 1998;24(4):44-50.

8. Kamel HK, Hajjar RR. Sexuality in the nursing home, part 2: Managing abnormal behavior - legal and ethical issues. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4(4):203-206.

9. Scott K, Lawrence RM, Duggal A, Darwin C, Brooks E, Christodoulou G. Prescribing patterns for psychotic and behavioural symptoms in dementia: a national survey. The Psychiatrist. 2002;26(8):288-290.

10. Rosenthal M, Berkman P, Shapira A, Gil I, Abramovitz J. Urethral masturbation and sexual disinhibition in dementia: a case report. Isr Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2003;40(1):67-72.

11. Series H, Degano P. Hypersexuality in dementia. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2005;11(6):424-431.

12. Dhikav V, Anand K, Aggarwal N. Grossly disinhibited sexual behaviour in dementia of Alzheimer’s type. Arch Sex Behav. 2007; 36(2):133-134.

13. Prakash R, Pathak A, Munda S, Bagati D. Quetiapine effective in treatment of inappropriate sexual behaviour of Lewy body disease with predominant frontal lobe signs. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2009;24(2):136-140.

14. MacKnight C, Rojas-Fernandez, C. Quetiapine for sexually inappropriate behaviour in dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(6):707-711.

15. Reeves RR, Perry CL. Aripiprazole for sexually inappropriate vocalizations in frontotemporal dementia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(1):145-146.

16. Shilpa S, Weinberg AD. Pharmacologic treatment of sexual inappropriateness in long-term care residents with dementia. Ann Long-Term Care: Clin Care Aging. 2006;14(10). https://www.annalsoflongtermcare.com/article/sexual-inappropriate-elderly-long-term-care-pharmacologic-treatment-dementia. Published online September 5, 2008. Accessed May 28, 2015.

17. Stewart JT, Shin KJ. Paroxetine treatment of sexual disinhibition in dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(10):1474.

18. Tosto G, Talarico G, Lenzi GL, Bruno G. Effect of citalopram in treating hypersexuality in an Alzheimer’s disease case. Neurol Sci. 2008;29(4):269-270.

19. Mania I, Evcimen H, Mathews M. Citalopram treatment for inappropriate sexual behaviour in a cognitively impaired patient. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8(2):106.

20. Leo RJ, Kim KY. Clomipramine treatment of paraphilias in elderly demented patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1995;8(2):123-124.

21. Perilstein RD, Lipper S, Friedman LJ. Three cases of paraphilias responsive to fluoxetine treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52(4):169-170.

22. Freymann N, Michael R, Dodel R, Jessen F. Successful treatment of sexual disinhibition in dementia with carbamazepine - a case report. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2005;38(3):144-145.

23. Alkhalil C, Hahar N, Alkhalil B, Zavros G, Lowenthal D. Can gabapentin be a safe alternative to hormonal therapy in the treatment in inappropriate sexual behaviour in demented patients? Int Urol Nephrol. 2003;35(2):299-302.

24. Alkhalil C, Tanvir F, Alkhalil B, Lowenthal DT. Treatment of sexual disinhibition in dementia: case reports and review of the literature. Am J Ther. 2004;11(3):231-235.

25. Miller LJ. Gabapentin for treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35(4):427-431.

26. Jensen CF. Hypersexual agitation in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(9):917.

27. Cooper AJ. Medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) treatment of sexual acting out in men suffering from dementia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48(9):368-370.

28. Weiner MF, Denke M, Williams K, Guzman R. Intramuscular medroxyprogesterone acetate for sexual aggression in elderly men. Lancet. 1992;339(8801):1121-1122.

29. Light SA, Holroyd S. The use of medroxyprogesterone acetate for the treatment of sexually inappropriate behaviour in patients with dementia. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006;31(2):132-134.

30. Balasubramaniam M, Clark LM, Jensen TP, Alici Y. Medroxyprogesterone acetate treatment for sexually inappropriate behaviour in a patient with frontotemporal dementia. Ann Long-Term Care: Clin Care Aging. 2013;21(11):30-36.

31. Haussermann P, Goeker D, Beier K, Schroeder S. Low-dose cyproterone acetate treatment of sexual acting out in men with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2003;15(2):181-186.

32. Nadal M, Allgulander S. Normalization of sexual behaviour in a female with dementia after treatment with cyproterone. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 1993;8(3):265-267.

33. Kyomen HH, Nobel KW, Wei JY. The use of estrogen to decrease aggressive physical behaviour in elderly men with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(11):1110–1112.

34. Ott BR. Leuprolide treatment of sexual aggression in a patient with dementia and the Klüver-Bucy syndrome. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1995:18(5):443-447.

35. Wiseman SV, McAuley JW, Freidenberg GR, Freidenberg DL. Hypersexuality in patients with dementia: possible response to cimetidine. Neurology. 2000;54(10):2024.

36. Na HR, Lee JW, Park SM, Ko SB, Kim S, Cho ST. Inappropriate sexual behaviours in patients with vascular dementia: possible response to finasteride. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(11):2161-62.

37. Alagiakrishnan K, Sclater A, Robertson D. Role of cholinesterase inhibitor in the management of sexual aggression in an elderly demented woman. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(9):1326.

38. Chemali Z. Donepezil and hypersexuality: a report of two cases. Primary Psychiatry. 2003;10:78-79.

39. Knight C, Alderman N, Johnson C, Green S, Birkett-Swan L, Yorstan G. The St Andrew’s Sexual Behaviour Assessment (SASBA): development of a standardised recording instrument for the measurement and assessment of challenging sexual behaviour in people with progressive and acquired neurological impairment. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2008;18(2):129-159.

40. Knigge U, Dejgaard A, Wollesen F, Ingerslev O, Bennett P, Christiansen PM. The acute and long term effect of the H2- receptor antagonist cimetidine and ranitidine on the pituitary gonadal axis in men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1983;18(3):307-313.

41. Winters SJ, Banks JL, Loriaux DL. Cimetidine is an antiandrogen in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1979;76(3):504-508.

42. The American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:616−631.

43. Sonnenblick M, Rosin AJ, Weissberg N. Neurological and psychiatric side effects of cimetidine- report of 3 cases with review of the literature. Postgrad Med J. 1982;58(681):415-418.