Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis Resulting From Herpes Zoster Infection in an Older Adult

Herpes zoster or shingles occurs due to reactivation of latent varicella zoster virus (VZV). The most common neurological sequel of herpes zoster is post-herpetic neuralgia. Cranial nerve palsies, meningoencephalitis, cerebellitis, zoster paresis, and vasculopathy can also ensue after reactivation of VZV. Recently, much literature has been published about VZV vasculopathy causing strokes, multifocal vasculopathy mimicking giant cell arteritis, extra cranial vasculopathy, ischemic cranial neuropathy, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, spinal cord infarction, and peripheral thrombotic disease. However, the pathogenesis of VZV vasculopathy remains elusive and early recognition of this entity is a clinical challenge. The authors report an unusual case of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in an elderly woman during an episode of shingles that posed a significant diagnostic dilemma.

Key words: complication, neurological, reactivation, thrombosis, varicella, vasculopathy.

Herpes zoster, or shingles, occurs from reactivation of latent varicella zoster virus (VZV) and is characterized by painful cutaneous eruptions along a dermatomal distribution. Neurological complications such as postherpetic neuralgia is common after herpes zoster infection; however, it can also cause vasculopathy, myelitis, necrotizing retinitis, and zoster sine herpete.1

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) is a very rare complication of herpes zoster and occurs due to VZV vasculopathy. Most of the earlier literature on VZV vasculopathy describe it as a disease affecting predominantly large arteries causing strokes and transient ischemic attack.2 More recent studies have expanded the clinical spectrum of VZV vasculopathy to include aneurysms, dissection, ischemic cranial neuropathies, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and spinal cord infarction.3 Though the exact pathogenic mechanism of vasculopathy is unclear, evidence points to productive viral infection within the vascular endothelium, leading to inflammation and vascular wall remodeling, which promote thrombosis.4 An acquired hypercoagulable state resulting from decreased levels of natural anticoagulants in the viremic phase of the infection is also postulated to provoke thrombosis.5-7 We report herein a rare occurrence of CVST in a septuagenarian during an episode of shingles.

Case Presentation

A 71-year-old white woman presented initially to the emergency department (ED) with complaints of intractable headache in the base of the skull and left occipital area. Preliminary evaluation with a computerized tomography (CT) scan of the head was noncontributory. She was sent home with pain medication for suspected basilar migraine and advised to follow up with her primary care physician. She returned 2 days later with worsening headache and confusion and was admitted to the hospital. Significant medical history included non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; stage 1 uterine cancer, for which she underwent total abdominal hysterectomy; and thyroid cancer, which was treated with radioactive iodine and total thyroidectomy. In the ED, the patient was drowsy, responded to verbal commands, and was oriented to person but not to time and place. Examination of the fundus did not show any papilledema, and motor strength and reflexes were within normal limits. There was no meningismus; however, she complained of pain on the left side of her neck and face, which was aggravated by even slight touch. Laboratory studies showed normal blood count and sedimentation rate. Blood chemistry was unremarkable except for mild hyperglycemia.

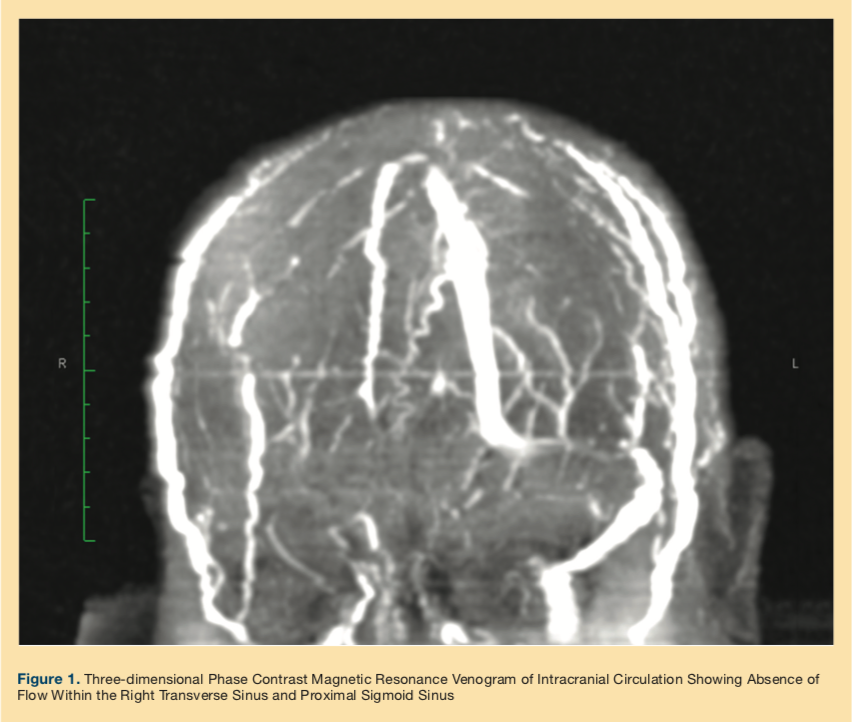

The patient continued to experience intractable headache and hyperalgesia on the left side of her head, raising concerns for a giant cell arteritis (GCA); however, she lacked other typical features of GCA. Neurology was consulted, and further workup with CT angiogram showed a filling defect in the right transverse and sigmoid sinus. A subsequent three-dimensional phase magnetic resonance venogram (MRV) of the brain (Figure 1) confirmed the diagnosis of CVST, and immediate anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin was started.

The next day, the patient developed some oozing sores behind her left ear and base of scalp, resembling shingles. An urgent ophthalmological consult was placed to rule out ocular involvement given the proximity of the rash to the trigeminal nerve distribution, and intravenous acyclovir was commenced. A complete hypercoagulable workup was ordered to evaluate the cause of CVST, and multiple imaging studies were done to search for an occult malignancy given her history of uterine and thyroid cancer. No primary or metastatic focus was identified on CT studies or blood work. Lupus anticoagulant test was normal, prothrombin gene and factor V Leiden mutation were absent. Protein C activity and protein S activity were appropriately normal, electrophoresis did not show any monoclonal gammopathy, and flow cytometry was negative for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria and lymphoma.

During the entire hospitalization, the patient continued to receive unfractionated heparin and was also initiated on warfarin. She was bridged appropriately with unfractionated heparin until her international normalized ratio was in the therapeutic range. Her headaches improved marginally, but mental status reverted to baseline. Prednisone was avoided due to her history of diabetes mellitus, but she was provided oxycodone to help with pain. As she did not have any signs of ophthalmic involvement, she was switched to oral acyclovir. Despite being appropriately treated for CVST and herpes zoster, she continued to have severe pain, deconditioning, and physical limitation that eventually required skilled therapy and placement in an assisted living facility.

Discussion

Risk factors for developing herpes zoster include increasing age, immunocompromised state, female sex, higher social economic status, diabetes, history of cancer, psychological stress, and treatment with antitumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors.8 The patient described here had several of these risk factors, including age, gender, diabetes, and history of cancer, all of which could have made her vulnerable to herpes zoster infection.

Cell mediated immunity is responsible for the long dormancy of VZV within the dorsal root/cranial root ganglia after the initial infective phase. With senescence, there is decreased cell mediated immunity, and the virus undergoes reactivation, travels along the sensory axon to the epithelium, causing a skin rash within the dermatome innervated by the afflicted sensory nerve.9

As VZV is a highly neurotropic virus, neurological complications are expected following either primary VZV infection or reactivation. Opthalmoplegia can occur if cranial nerves II, IV, or VI are involved, if geniculate ganglion is affected then Bell’s palsy may ensue or if the auditory nerve is affected, Ramsey Hunt syndrome and zoster oticus occur. The most dangerous condition is herpes zoster opthalmicus with involvement of the first division of trigeminal nerve, which can result in keratitis and vision loss.1 Other rare neurological manifestations of zoster include VZV vasculopathy, myelitis, meningo-encephalitis, and cerebellar ataxia.

Among all neurological complications, postherpetic neuralgia is the most common, seen in up to 40% of the geriatric population.10 Herpes zoster and postherpetic neurological complications can have a devastating impact on patient’s quality of life and may cause permanent physical impairment.11 Zoster vaccine not only reduces the incidence of herpes zoster but also minimizes postherpetic complications and is recommended for everyone over the age of 60 years.12 Though clinical efficacy of zoster vaccine is limited beyond 5 to 8 years postvaccination, there is still some arguable benefit to protecting against herpes zoster and its debilitating complications.13 The patient described here had not received the zoster vaccine, which could have complicated her clinical course resulting in debility and some loss of independent function.

VZV is also emerging as an important cause of some vascular phenomenon which had previously been poorly understood. Recent literature has shed light on VZV vasculopathy and its association with unusual neurological presentations such as ischemic cranial neuropathies, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and spinal cord infarction.3 VZV vasculopathy can occur after a primary varicella infection or zoster and can affect both immunocompetent and immunosuppressed individuals. It is predominantly arterial and can involve large as well as small sized arteries.2 VZV vasculopathy also has been linked with GCA, which presents as headache, scalp tenderness, and visual disturbance in the elderly. Clinico-virologic studies from patients with clinically suspected GCA but pathologically negative temporal artery biopsies revealed infection with varicella-zoster virus.14 The patient described here had intractable headache and scalp tenderness, though GCA was in the differential diagnosis. Treatment with steroid was deferred and a CT angiogram was performed which revealed dural venous sinus thrombosis. Steroids forms the mainstay of treatment of GCA; it is, however, contraindicated in VZV vasculopathy as it would promote viral replication and further vessel wall damage.

Although exact pathogenesis of VZV vasculopathy is still unclear, autopsy studies show endothelial cells injury, myofibroblast proliferation, inflammation, and disruption of internal elastic lamina, which is thought to result in thrombosis, aneurysms, and dissection.12 Presence of anti-VZV IgG antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with central nervous system vasculopathy manifesting as stroke or transient ischemic attack also support the theory of productive viral infection within cerebral vasculature.15 Akin to cerebral thrombi, peripheral vascular thrombosis can also occur with VZV vasculopathy.16

Maity et al5 described extensive bilateral lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in a 24-year-old immunocompetent male after VZV reactivation. Purpura fulminans in the setting of a primary varicella infection is well described in the literature. It is characterized by disseminated micro-thrombi in both arterial and venous circulation and thought to result from acquired deficiency of circulating proteins C and S.17 Siddiqi et al6 reported two cases of CVST in the absence of purpura fulminans in adolescent boys, which the authors attributed to a postinfectious immunological reaction that led to a hypercoagulable state. This same mechanism can also result in CVST, a rare form of DVT. CVST can also occur due to an acquired thrombophilic state due to transient reduction in the levels of naturally occurring anticoagulants in the body during the viremic phase of varicella.7 Zoster sine herpete, a condition where neurological complications occur in the absence of the classic zoster rash, is particularly associated with VZV vasculopathy. It is believed that in such cases a nonseptic thrombophlebitis results in cerebral sinus thrombosis.18

CVST is a common cause of headache among children and women in childbearing age and usually has a good prognosis.19 In the geriatric population, CVST carries a poorer prognosis. It presents with delirium or mental status change and diagnosis is often delayed due to atypical presentation. A thorough evaluation for acquired pro-thrombotic states is usually required in elderly patients with CVST, and anticoagulation for longer than 6 months is needed as these patients are at an increased risk of further thrombotic events.20

Our patient presented with headaches initially and later developed confusion. These events preceded the development of the zoster rash. Due to the intractable pain and worsening mental status, a more extensive neurologic workup was pursued with CT angiogram and MRV that helped confirm the diagnosis of CVST. Routine blood and genetic test done to evaluate hypercoagulability were normal and there was no occult malignancy detected on imaging that could have caused a thrombotic state. Interestingly, she developed the classic zoster rash on the left side while the thrombosis was on the right, adding to the conundrum over the exact pathogenesis of CVST. There was no CSF analysis done to confirm the presence of VZV antibodies; hence direct causation could not be established. However, in light of herpes zoster infection and concurrent CVST, we hypothesize that the left-sided pain was a manifestation of allodynia associated with herpes zoster; reactivation of the varicella virus caused a local inflammation and induced a transient hypercoagulable state, leading to vasculopathy and DVT of the cerebral sinuses in the vicinity.

Conclusion

Though herpes zoster is common in the geriatric population, CVST as its consequence is very unusual. It is important to maintain a high index of suspicion for this rare complication to prevent any delay in treatment. Vaccinating seniors against herpes zoster is also another important aspect to consider, as many disabling consequences can be averted and rare post-herpetic neurological complications can be minimized.

1. Nagel MA, Gilden DH. The protean neurologic manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74(7):489-494, 496, 498-499.

2. Gilden D, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, Nagel MA. Varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: diverse clinical manifestations, laboratory features, pathogenesis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(8):731-740.

3. Nagel MA, Gilden D. Update on varicella zoster virus vasculopathy. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2014;16(6):407.

4. Gilden D, Mahalingam R, Nagel MA, Pugazhenthi S, Cohrs RJ. The neurobiology of varicella zoster virus infection. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2011;37(5):441-463.

5. Maity PK, Chakrabarti N, Mondal M, Patar K, Mukhopadhyay M. Deep vein thrombosis: a rare signature of herpes zoster. J Assoc Physicians India. 2014;62(1):72-74.

6. Siddiqi SA, Nishat S, Kanwar D, Ali F, Azeemuddin M, Wasay M. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: association with primary varicella zoster virus infection. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012; 21(8):917.e1-917.e4.

7. Sudhaker B, Dnyaneshwar MP, Jaidip CR, Rao SM. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) secondary to varicella induced hypercoagulable state in an adult. Intern Med Inside. 2014; 2:1.

8. Weitzman D, Shavit O, Stein M, Cohen R, Chodick G, Shalev V. A population based study of the epidemiology of Herpes Zoster and its complications. J Infect. 2013;67(5):463-469.

9. Gershon AA, Gershon MD, Breuer J, Levin MJ, Oaklander AL, Griffiths PD. Advances in the understanding of the pathogenesis and epidemiology of herpes zoster. J Clin Virol. 2010;48(suppl 1):S2-S7.

10. Kawai K, Gebremeskel BG, Acosta CJ. Systematic review of incidence and complications of herpes zoster: towards a global perspective. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):e004833.

11. Johnson RW, Bouhassira D, Kassianos G, Leplège A, Schmader KE, Weinke T. The impact of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia on quality-of-life. BMC Med. 2010;8:37.

12. Gilden D, Nagel MA, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R. The variegate neurological manifestations of varicella zoster virus infection. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013; 13(9):374.

13. Morrison VA, Johnson GR, Schmader KE, et al. Long-term persistence of zoster vaccine efficacy. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(6):900-909.

14. Gilden D, White T, Khmeleva N, et al. Prevalence and distribution of VZV in temporal arteries of patients with giant cell arteritis. Neurology. 2015;84(19):1948-1955.

15. Gilden DH, Lipton HL, Wolf JS, et al. Two patients with unusual forms of varicella-zoster virus vasculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(19):1500-1503.

16. Limb J, Binning A. Thrombosis associated with varicella zoster in an adult. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(6):e498-e500.

17. Dogan M, Acikgoz M, Bora A, Basaranoglu M, Oner AF. Varicella-associated purpura fulminans and multiple deep vein thromboses: a case report. J Nippon Med Sch. 2009;76(3):165-168.

18. Chan J, Bergstrom RT, Lanza DC, Oas JG. Lateral sinus thrombosis associated with zoster sine herpete. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25(5):357-360.

19. Bousser MG, Ferro JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis: an update. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(2):162-170.

20. Ferro JM, Canh√£o P, Bousser M-G, Stam J, Barinagarrementeria F; ISCVT Investigators. Cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis in elderly patients. Stroke. 2005;36(9):1927-1932.