Ceftriaxone-Induced Immune Hemolytic Anemia in a Nonagenarian Identified at a Skilled Nursing Facility

Abstract: Drug-induced hemolytic anemia is an extremely rare phenomenon. Authors describe a case of ceftriaxone-induced immune hemolytic anemia discovered in a nonagenarian woman at a skilled nursing facility (SNF). The 90-year-old woman had presented to the hospital with worsening back pain secondary to vertebral osteomyelitis. Ceftriaxone was initiated, and she was subsequently discharged to the SNF. Per her laboratory results, hemoglobin and hematocrit were found to have dropped precipitously. With no evidence of bleeding and a low haptoglobin level, a diagnosis of drug-induced hemolytic anemia was considered. Pursuing this theory, her antibiotic was switched and subsequent blood work confirmed the proposed diagnosis. To our knowledge, this is the oldest patient to have had this reaction and the first diagnosed in an unlikely setting, an SNF. This case serves to increase awareness of this rare, often fatal adverse effect of a common medication.

Key words: ceftriaxone, hemolysis, drug-induced hemolytic anemia, nonagenarian, adverse drug reaction

As time goes on, more medical care will be delivered in post-acute care (PAC) settings across the United States, which includes skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). The US medical system will be more dependent on these other venues of care, especially as the population ages exponentially. PAC facilities benefit the health care system in various ways; for example, they reduce inappropriate hospital readmissions, allow hospitals to off-load patients so that they can meet their length-of-stay targets, and allow for patients to participate in rehabilitative therapy while still receiving medical care in a monitored setting. Discharges from hospitals to PACs have risen by approximately 50%, according to a study looking at data of a nationally representative sample of patients over a 15-year period from 1996 to 2010, which also found that hospital lengths of stay progressively decreased over time.1

Subsequently, the role of the physician in SNFs will evolve over time. Patients spend a substantial amount of time in a SNF, with 23 days as the average length of stay;2 however, despite the fact that these patients have 24-hour nursing care provided to them, these patients do not necessarily require daily physician visits or have daily blood draws. As a result, some drug reactions, especially rare reactions such as the one described in this case, may be overlooked during a resident’s SNF stay.

Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia (DIIHA) is rare, with estimates at around 1 incident in 1 million of the population.3 DIIHA has been attributed to over 100 different drugs, of which antimicrobials make up a large portion. The first case of ceftriaxone-induced hemolysis was reported in 1991 by Garratty and colleagues.4 In 2009, it was reported that there have been approximately 81 cases of cephalosporin-induced immune hemolytic anemia in the literature as of 2005.5

This article details the case of a nonagenarian woman who had previously been admitted to the emergency department (ED) with worsening lower back pain due to suspected vertebral osteomyelitis where she had been treated with ceftriaxone intravenously in addition to receiving other interventions. The woman was later discharged to the authors’ SNF with instructions for continuing her therapy. At the SNF, she was found to be suddenly and profoundly anemic with laboratory findings suggestive of hemolysis, thought to be associated with her antibiotic therapy. This case highlights the diagnostic and treatment measures in DIIHA. It underlines the importance of having a high clinical suspicion in similar circumstances to hopefully intervene and prevent any potential adverse effects.

Case Presentation

A 90-year-old, high-functioning woman had presented to the ED for worsening lower back pain. She had a past medical history of hypertension, cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma, and chronic back pain secondary to spinal stenosis. She had no known allergies. Of note, approximately 3 weeks prior to presentation at the ED, the patient received an epidural steroid injection. She had had epidural injections in the past with pain relief lasting many months.

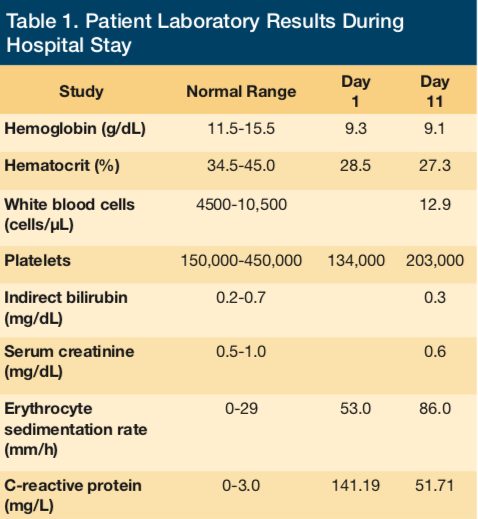

Upon admission to the ED for evaluation and management of her intractable back pain, initial physical exam was significant for a subconjunctival hemorrhage and a murmur. Admission laboratory results were as follows: hemoglobin 9.3 g/dL, hematocrit 28.5%, platelets 134,000/μL, international normalized ratio (INR) 1.05, white blood cells 13,400/μL, blood urea nitrogen 19 mg/dL, creatinine 0.5 mg/dL, total bilirubin 1.1 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 0.4 mg/dL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 53 mm/hr, and C-reactive protein 141.19 mg/L. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine was performed in the ED, revealing L2-L3 discitis and osteomyelitis with associated epidural enhancement and without discrete collection. The patient was administered 1 g ceftriaxone intravenously in the ED. Blood cultures were obtained in the ED prior to the administration of the antibiotic.

The patient was found to be in new-onset atrial fibrillation on presentation to the ED, besides presenting with her chief complaint of severe back pain. Oral diltiazem was initiated for heart rate control. Infectious disease, cardiology, and neurosurgery services were consulted. The infectious disease consultant recommended to continue ceftriaxone at a dose of 1 g intravenously once daily and obtain a bone biopsy. The cardiologist recommended to continue diltiazem and initiate a heparin infusion. The neurosurgical consultant recommended nonsurgical treatment including pain control, physical therapy, and use of a thoraco-lumbar sacral orthosis for support. A request was placed for interventional radiology to obtain a bone biopsy.

A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed, revealing an estimated left ventricular ejection fraction of 60% to 65%, severe tricuspid regurgitation, severe mitral regurgitation, prolapse of the posterior mitral valve leaflet, and moderate aortic regurgitation.

On hospital day 4, the initial blood cultures from the day of admission returned positive for (pan-sensitive) Streptococcus viridans in both sets. The dose of intravenous ceftriaxone was increased to 2 g twice daily, given the bacteremia. Because the patient had an identifiable organism in the blood, the bone biopsy was no longer sought. She was subsequently transitioned from heparin to warfarin therapy.

On hospital day 8, a transesophageal echocardiogram was performed, revealing severe mitral regurgitation, severe mitral valve prolapse, mild to moderate tricuspid regurgitation, and a possible small vegetation on the mitral valve that could not be excluded. Once the patient’s bacteremia had cleared, her dose of ceftriaxone was then decreased to 2 g once daily. The patient had a central catheter peripherally inserted and was eventually discharged to the SNF for PAC on hospital day 15 with instruction to complete a total of 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotic therapy.

Upon the patient’s SNF admission, she was on the following medications: warfarin sodium (dosed per INR), aspirin 325 mg once daily, intravenous ceftriaxone 2 g once daily, multivitamin 1 tablet once daily, diltiazem 90 mg every 6 hours, ferrous sulfate 325 mg once daily, furosemide 20 mg once daily, pantoprazole 20 mg once daily, and docusate sodium 200 mg once daily.

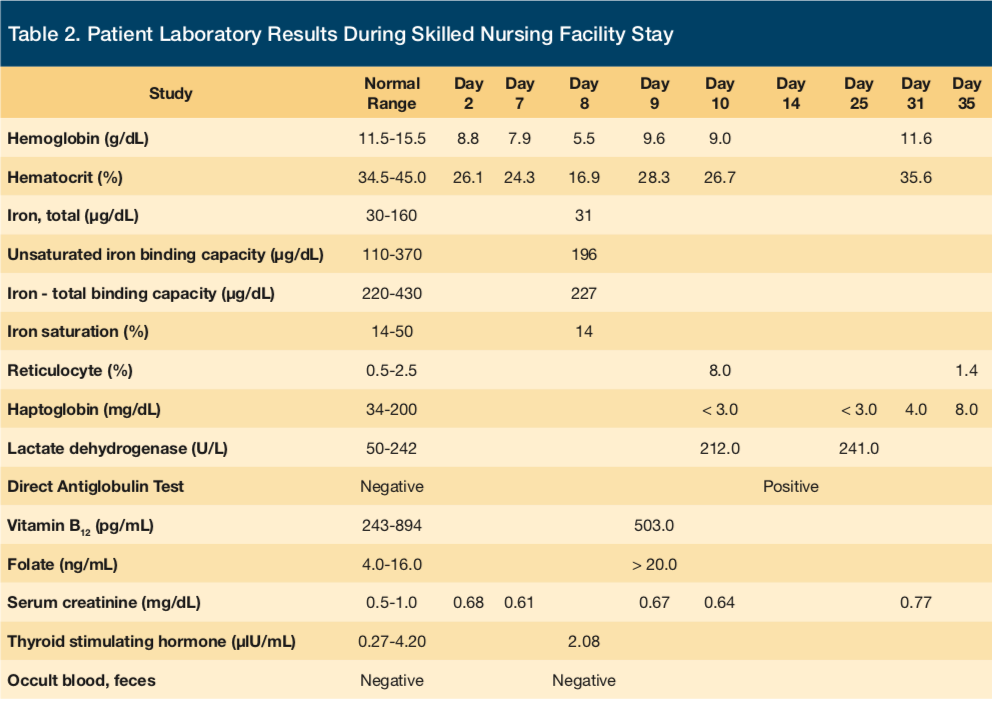

On day 8 of the patient’s SNF stay, a sharp decrease in hemoglobin and hematocrit values (nadir, 5.5 g/dL and 16.9%, respectively) was recognized. Clinically, the patient did not show any evident signs of bleeding. Her vital signs remained normal throughout her entire stay at the rehabilitation center, without any fever or hypotension. Urinalysis was not performed. Fecal occult blood testing was negative. An anemia workup was subsequently undertaken, and hematology service was consulted.

Laboratory values (Tables 1 and 2) revealed a low haptoglobin level of < 3 mg/dL (normal range 34-200 mg/dL) and an increased reticulocyte count of 8% (normal range 0.5%-2.5%). Lactate dehydrogenase was normal at 212 U/L. Renal function remained stable. The INR level was appropriately elevated due to warfarin therapy and was never significantly supratherapeutic. The hematology consultation team had recommended to discontinue ceftriaxone as it was considered a possible cause of an apparent hemolytic anemia. The antibiotic was switched to intravenous vancomycin to complete the duration of therapy for lumbar discitis, vertebral osteomyelitis, and possible infective endocarditis.

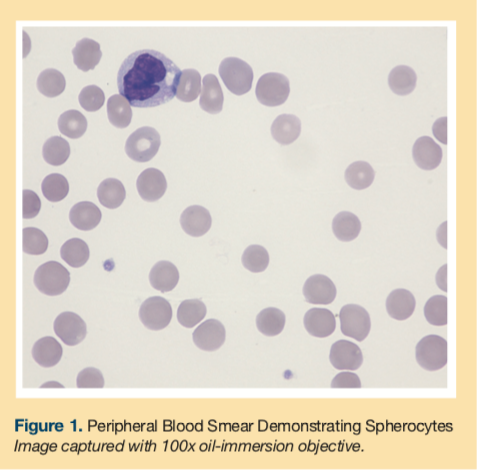

A peripheral blood smear was obtained showing normocytic normochromic red blood cells and spherocytes (Figure 1). The smear did not reveal any schistocytes or microcytosis. A polyspecific direct antiglobulin test (DAT) revealed a positive result (1+), and monospecific reagents confirmed complement sensitization only [anti-C3 positive (1+), anti-IgG negative]. Type and screen revealed the patient had type O and Rh-positive blood.

The patient was transfused 2 half units of packed red blood cells for severe anemia with a resulting elevation of hemoglobin to 9.6 g/dL. Hemoglobin and hematocrit levels increased more than appropriately for one total unit of blood transfused, further suggesting that there was another process, namely hemolysis, that had occurred. The patient could not recall if she had ever received this drug before. She was instructed to avoid receiving ceftriaxone and other similar drugs in the future.

Discussion

This case was managed successfully with discontinuation of ceftriaxone and with supportive measures. Ceftriaxone was strongly suspected as the culprit drug causing hemolysis for many reasons. First, the patient’s other medications are not known to cause DIIHA to the degree that antimicrobials are. Secondly, the aspirin and warfarin were not felt to be playing a role, as an acute blood loss scenario did not occur. Her negative fecal occult blood testing, continued hemodynamic stability, and improvement—despite no interruption of her other medications—all pointed away from blood loss as a cause for her anemia. Lastly, the evident hemolysis, based on laboratory data including DAT positivity along with improvement upon cessation of ceftriaxone, all essentially confirmed the initial diagnosis. This was a probable adverse reaction to ceftriaxone, with a Naranjo algorithm6 score of 7.

Once ceftriaxone is stopped, hematologic recovery is usually rapid,7 as was seen in this patient. Providers caring for older adults in PAC settings that accommodate parenteral therapy must be vigilant and pay careful attention to trends in laboratory values while also taking note of patients’ clinical situation and symptoms. This rare reaction should be suspected if there is a marked drop in hemoglobin and hematocrit values in the absence of clinical signs of bleeding.

An extensive literature review shows ceftriaxone can be associated with drug-induced immune hemolysis that occurs mostly in pediatric patients, but this case highlights that this reaction can even occur in the most unlikely age group, namely nonagenarians. The pediatric cases have included patients that have overwhelmingly suffered from underlying hematologic or immunologic disorders, such as sickle cell disease, leukemia, Crohn disease, and HIV.8

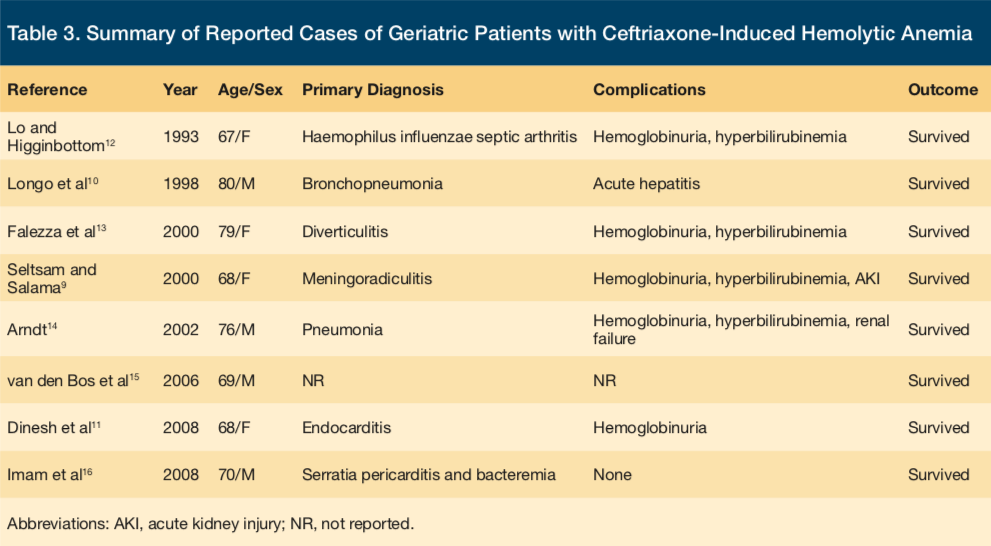

In adults aged 65 and older, there are eight prior reports of ceftriaxone-induced immune hemolytic anemia (CIIHA) in the literature to date (See Table 3 for a detailed view of the reported cases).9-16 The oldest patient recorded to have had this phenomenon occur was an 80-year-old man in France.10 None of the previously reported cases have resulted in death, but there are many possible adverse effects that may occur during the hemolytic reaction. A fatal outcome is more common in CIIHA than in immune hemolytic anemia associated with other drugs.9 To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this presented case is the oldest individual reported to have had this reaction and would be the only person to be a part of the oldest-old segment of the geriatric population thus far (typically defined as adults aged 85 and older), the fastest growing segment of the total American population.17

The woman experienced this hemolytic reaction at the SNF approximately 23 days after she was first administered the medication in the ED during her hospital stay. Previous studies show that the reaction onset takes substantially longer on average in adults than in children. For example, in the pediatric population, the reaction becomes apparent after anywhere from 5 minutes to 7 days and 30 minutes to 34 days in the adult population.18 Thus, the reaction onset can vary widely and can affect individuals either immediately or up to hours after a single dose. The actual dose that elicits the reaction can also vary, with some individuals becoming affected after the first dose or after repeated doses of the medication, as was the case in this patient.

Patients that are acutely hospitalized are probably more likely to have this reaction detected and diagnosed earlier, since patients are seen on a daily basis and blood work is usually drawn more frequently compared with residents in an SNF. In medical practice today, it is more common to send patients home either from the hospital or from an SNF with an intravenous catheter and have a nurse visit the home to administer the remaining course of antimicrobial therapy. In at least one previously reported case from New Zealand, the patient was treated at home in this way. The patient returned to the hospital after becoming severely symptomatic with presyncope while reportedly having back pain, abdominal pain, and dark-colored urine in the preceding week. The patient was ultimately found to have CIIHA.11 In cases similar to this, such as in the presented case, it is imperative to consider and test for this potential adverse effect. The Infectious Diseases Society of America suggests that a complete blood count and renal function tests be performed at least once weekly when a patient is treated with cephalosporins during outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy.19

In this case, the patient was instructed to report this adverse effect if she is ever administered an antibiotic in the future. Cephalosporin antibiotics as a drug class should be avoided in those who have had a hemolytic reaction (or any other significant adverse effect) to ceftriaxone because of potential crossreactivity.9 Clinicians should entertain a high clinical suspicion when treating a patient under similar circumstances in the hopes to intervene early enough to avoid any serious effects that may result.

Conclusion

This case highlights the potential severity of DIIHA. Prompt recognition and discontinuation of the offending agent can be lifesaving. The diagnostic and treatment details of this case are valuable for increasing awareness of this rare, and potentially fatal, phenomenon involving a commonly used medication in an older adult in a PAC facility.

To read more articles in this issue, visit the 2017 November/December issue page

To read more ALTC expert commentary and news, visit the homepage

References

1. Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Rise of post-acute care facilities as a discharge destination of US hospitalizations. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):295-296.

2. Levy C, Epstein A, Landry L, et al. Literature review and synthesis of physician practices in nursing homes. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation website. https://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/phypraclr.htm. Published October 17, 2005. Accessed October 20, 2017.

3. Garratty G. Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009;73-79.

4. Garratty G, Postoway, N, Schwellenbach J, McMahill PC. A fatal case of ceftriaxone (Rocephin) induced hemolytic anemia associated with intravascular immune hemolysis. Transfusion. 1991;31(2):176-179.

5. Williams CS, Shamdas GJ, Lo TS, Koo JM. A fatal case of ceftriaxone-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Hosp Physician. 2009;21-25.

6. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-245.

7. Petz LD, Garratty G. Immune Hemolytic Anemias. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone; 2004.

8. Quillen K, Lane C, Hu E, Pelton S, Bateman S. Prevalence of ceftriaxone-induced red blood cell antibodies in pediatric patients with sickle cell disease and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(4):357-358.

9. Seltsam A, Salama A. Ceftriaxone-induced immune haemolysis: two case reports and a concise review of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(9):1390-1394.

10. Longo F, Hastier P, Buckley MJM, Chichmanian RM, Delmont JP. Acute hepatitis, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, and erythroblastocytopenia induced by ceftriaxone. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(5):836-837.

11. Dinesh D, Dugan N, Carter J. Intravascular haemolysis in a patient on ceftriaxone with demonstration of anticeftriaxone antibodies. Intern Med J. 2008;38(6):438-441.

12. Lo G, Higginbottom P. Ceftriaxone induced hemolytic anemia. Transfusion. 1993;33:25S.

13. Falezza GC, Piccoli PL, Franchini M, Gandini G, Aprili G. Ceftriaxone-induced hemolysis in an adult. Transfusion. 2000;40(12):1543-1544.

14. Arndt PA. Practical aspects of investigating drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia due to cefotetan or ceftriaxone-a case study approach. Immunohematology. 2002;18(2):27-32.

15. van den Bos AG, Gerrits-Kuiper J, Moors MHPO, Novotny VMJ. Adverse haemolytic transfusion events: consider the role of drugs. Vox Sanguinis. 2006;91(suppl 3):144.

16. Imam SN, Wright K, Bhoopalam N, Choudhury A. Hemolytic anemia from ceftriaxone in an elderly patient: a case report. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(8):610-611.

17. Werner CA. The older population: 2010 census briefs. US Census Bureau website. https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-09.pdf. Published November 2011. Accessed October 20, 2017.

18. Kapur G, Valentini RP, Mattoo TK, Warrier I, Imam AA. Ceftriaxone induced hemolysis complicated by acute renal failure. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(1):139-142.

19. Tice AD, Rehm SJ, Dalovisio JR, et al. Practice guidelines for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy. IDSA guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(12):1651-1672.