A Case of Peyronie Disease and Priapism Resulting From a 10-Year-Old Penile Prosthesis in a Patient With Dementia

Abstract: A community-dwelling, 79-year-old man with a history of moderate dementia presented to a clinic with his spouse to establish care. His spouse reported increased physical agitation, worsening at night, for the last several months. He had a penile prosthesis implanted 10 years prior. Upon examination, an intermittently high post-void residual volume was identified, which was explained by a mechanical interruption from urethral strictures from otherwise asymptomatic Peyronie disease, potentially causing mild priapism with inflation of the penile implant and consequently diminished urinary outflow. An intervention solution was then devised to improve patient’s quality of life. Providers should be aware of this potential problem unique to men as individuals age with implanted devices.

Key words: phenytoin, sertraline, SSRIs, drug interaction

Caring for dementia patients is a difficult task for both providers and caregivers.1,2 Behavioral symptoms are quite common in older adults with dementia.3 These behaviors range from reactive vocal gestures of yelling to physical agitation, pacing, kicking, hitting, and even sexual gestures, such as exposing, groping, and inappropriate contact.4 These behaviors not only cause significant difficulty for caregivers but also pose diagnostic challenges due to patients’ often limited ability to provide history and feedback. Unusual behaviors in dementia patients, such as psychomotor agitation or retardation, usually point to an unmet need, such as pain or discomfort, and could be an expression of some biopsychosocial distress.5 People with dementia have been shown to have disproportionately more pain and undiagnosed illnesses (such as urinary tract infection or anemia) than those without dementia.6

Medical devices in patients with dementia may be an issue often overlooked during care. It can be challenging for caregivers to properly place or adjust devices such as hearing aids, to ensure use of glasses for vision, and to dress the patients. In the presence of multiple coexisting conditions and previous implanted devices, such as cardiac pacemakers, ostomy bags, penile devices, etc, clinical recognition and assessment of patients’ needs can be even more complex.7

Over the past few decades, surgical advances in treatment of erectile dysfunction (ED), such as penile implants, have resulted in patients who are both outliving their devices’ shelf lives and who are experiencing cognitive impairments.8 Although the trend in and prevalence of such implants is currently in decline,9 prior popularity of these devices in men with ED may result in a growing number of older men living with both penile prosthesis (PP) implant and dementia. The annual incidence of PP implantation cases in the United States rose from 17,540 in 2000 to 22,420 in 2009.10 During this time, PP insertion for ED in men aged 65 to 74 was more prevalent.10 According to a more recent estimate, there is a generally declining trend for such implants for ED—the rate decreased from 4.6% in 2002 to 2.3% in 2010.9

Clinicians and caregivers are likely to face some unique challenges in caring for the subset of the aging population who received PP implants.11 Potential risks of long-term complications in a man with dementia may include penile erosion, ischemia, infections, and urinary obstruction. There is a paucity of data on long-term consequences of penile implant devices beyond 10 years; of the few long-term studies that have been done, researchers have found no significant problems with these implants after 5 and 10 years.12 However, studies that include patients with dementia are almost nonexistent, making it difficult to find effective, evidence-based interventions for these patients.

This article describes a case of an older man with dementia who had a PP implanted 10 years prior who presented with increased physical agitation, worsening at night, for the last several months. This case highlights the need for practitioners and caregivers to familiarize themselves with a basic understanding of how implanted penile devices work and how they can affect recipients over time.

Case Presentation

A 79-year-old man living in the community with a PP implant and a history of moderate dementia presented to the authors’ senior care clinic with his spouse to establish care. According to his spouse, the man had a history of controlled hypertension, osteoarthritis, and his PP was implanted 10 years ago. He was taking metoprolol, aspirin, and aricept daily. He had no history of hip or knee replacement or prostate cancer. Per chart review, the patient had a history of falls, pain, and difficulty ambulating.

His spouse reported that her husband had been demonstrating increased physical agitation, worse at night, for the last several months. This behavior was less frequent during the day and more pronounced during the night. His spouse said that he was getting out of bed and attempting to “open doors” at night, and it was difficult to redirect him. Directing him to the toilet sometimes “helped his agitation,” as noted by his spouse. She also reported that she observed him at times “fiddling with his scrotum” at night when taken to the bathroom. She noted that he seems uncomfortable with a notable erection as well, which “bends his penile shaft” more than it already bends. His agitation appeared to improve slightly, she said, when she was able to “turn that thing off,” apparently referring to the PP. The patient had an inflatable 3-piece implant that consists of a reservoir implanted in the abdomen, a pump placed in the scrotum, and a pair of cylinders implanted in the penis. The entire device is totally concealed in the body. To inflate the device and achieve an erection, the pump needs to be squeezed several times, moving the fluid into the cylinders placed in the penis. To deflate the device, the release valve needs to be pressed and held briefly to deactivate the pump (Figure 1).

On examination, he was pleasant and easily redirected, but he would get up from his chair intermittently and walk toward the door. When asked about pain or discomfort, he was unable to provide a reliable answer due to his cognitive status. Vitals were normal and physical exam was unremarkable, except the genital exam. His testicular exam was negative; the rectal exam showed mild, smooth enlargement of prostate. A markedly deviated penile shaft was clear upon observation (Figure 2). The shaft was palpated and partially straightened without any pain or discomfort. No skin breakdown or ulcers in the perineal area were noted. An attempt to examine scrotum was unsuccessful due to his agitation. Workup, including cell count and comprehensive panel, were normal. Based on his caregiver’s input and his exams, possible underlying causes of his discomfort to be investigated included benign prostatic hyperplasia with obstruction, urinary tract infection, prostatitis, priapism, and Peyronie disease.

The man was taken to the bathroom where he was directly observed urinating into the toilet while his wife stood close to him. The post-void residual volume was measured to be 150 cc. He was asked to wait for 25 minutes in the room for a repeat voiding trial. However, this time his wife was instructed to assist with his urination by keeping his penile shaft straighter during voiding. The shaft was gently manipulated during the process to avoid any pain or distress during the entire process. The urine stream and flow was notably improved with this intervention. Post-void volume was only 50 cc after the intervention. Urine dipstick in the office was negative for bacteria. His irritability was visibly improved during the remainder of his office visit.

His spouse was directed to follow the same intervention at home each time he urinated and to reduce his fluid intake in the evening. A urological consult was requested, and patient was scheduled for a follow-up in 2 weeks.

At the follow-up exam, his spouse reported that the frequency of irritability, pacing, and nighttime agitation was notably improved whenever she kept the shaft straighter during voiding. She also noted his penile tumescence was changed during his agitation. He was evaluated by urology, but no imaging study could be performed due to his inability to cooperate during his visit. A post-void trial was completed successfully in the urology clinic, and volume was measured to be 75 cc.

Urology determined that the implant was still functional; however, during assessment of the device with inflation, the patient became quite uncomfortable and agitated. Doppler tests could not be completed due to his cognitive status, and the physical exam of his penis to assess for plaque by the urologist made the patient anxious and triggered agitation. Ultimately, the urology exam finding was reported as likely plaque and a possible stricture from Peyronie disease. The intermittently high post-void residual volume was explained by a mechanical interruption from urethral strictures from otherwise asymptomatic Peyronie disease, potentially causing mild priapism with inflation of the penile implant and consequently diminished urinary outflow. A surgical intervention was not recommended unless ulceration or ischemia developed.

At the 6-week follow-up appointment, his wife reported that the intermittent agitation had improved with the combination of timed voiding, manually straightening his penile shaft during voiding, and preventing him inadvertently activating the device by means of tighter underwear and closer observation. However, his spouse was finding it more difficult to care for him due to the progression of the dementia. Three months later, he had a fall resulting in a hip fracture and subsequently was transferred to a nursing home.

Discussion

Based on the urology consult, asymptomatic Peyronie disease and mild priapism were ultimately determined to be the underlying causes of the patient’s discomfort and agitation. Peyronie disease, which primarily affects middle-aged to older men, is an acquired inflammatory condition of the penis associated with penile curvature and, in some cases, pain.13 The penile curvature associated with Peyronie disease is caused by an inelastic scar or plaque that shortens parts of the tunica albuginea of the corpora cavernosa during an erection.14 These plaques may cause the penis to be straight but shortened or to have a lateral bend. The circumference of the shaft may also be reduced.14 Radiographs of the penis may show calcification in 20% to 25% of patients with end-stage disease.15 Generally performed by a specialist, Doppler flow studies, along with dynamic infusion cavernosometry and cavernosography, could be helpful tests for demonstrating blood flow patterns in patients with penile plaques.15,16 The patient’s cognitive status and agitation prevented the completion of Doppler flow studies and imaging scans as well as a more thorough physical, which made definitive diagnoses difficult. Nonetheless, it was ultimately determined that the development of Peyronie disease led to his altered shaft curvature and symptoms of pain. His inadvertent activation of the pump, due to his cognitive deficits, resulting in a persistent erection was a potential contributor to his pain, since the 3-piece implant is easy to activate but its deactivation requires briefly holding the button placed in scrotum.

The first symptoms of Peyronie disease include focal pain with erection, new curvature with erection, or inability to penetrate due to curvature or flaccidity distal to the site of constriction.13 Some patients that do not experience pain with erection will have tenderness when the plaque is palpated.17 Pain typically improves as the initial inflammation subsides; however, the onset of new injuries to the corpora cavernosa may cause pain progression.14 Palpation of indurated plaques on physical examination of the penis may elicit pain if still in the inflammatory stage.17 In this case, since physical examination of the patient’s penile shaft did not display any sign of pain or discomfort, the diagnosis of priapism and Peyronie disease had appeared less likely on initial assessment. Also, Peyronie disease is more likely to be quite painful in the early stage, but it is not uncommon for pain to be minimal or only related to erection.13 Priapism caused by unintended activation of the PP device seemed to be the most likely explanation of his pain. Priapism is a persistent, usually painful erection that lasts for more than 4 hours and occurs without sexual stimulation.18 The condition is caused by changes in blood flow to the penile tissue from a variety of causes such as sickle cell anemia, leukemia, and medications.19 Although medications used for ED such as sildenafil can cause priapism, psychotropics such as fluoxetine, bupropion, and risperidone are also known for this side effect.20 In this case, a medication review and his history ruled out the iatrogenic cause for his condition (Table 1).

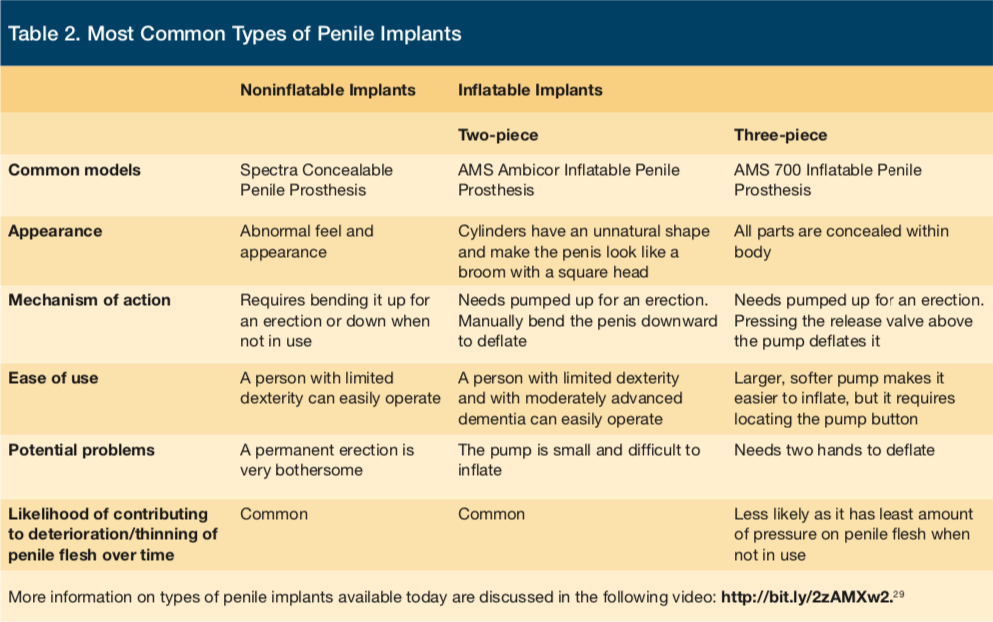

Although PP devices are generally deemed safe for long-term use12,21 and have an average life of 10 to 15 years,22 inadvertent activation of PP devices may become a bigger problem as men with implants age. Inadvertent activation may be less likely for individuals with advanced dementia and loss of dexterity if the implant mechanism requires locating the pump for use. As there are various types of penile implants (Table 2), complications and risks may vary. Differences in types of penile implants do not greatly impact rates of complication; however, the inflatable 3-piece PP requires placement of the reservoir in the lower abdomen, and the pump placement can lead to infections. Hematoma, swelling, and erosions of penile tissue are common complications.23

In general, caregivers should be made aware of the presence of any implants that patients have—penile or any others—particularly if they are totally or mostly concealed under the skin. Prior knowledge of a patient’s device will be helpful in avoiding any unnecessary concerns, especially over time. Although there is no standard nonsurgical treatment for Peyronie disease,4,24,25 spontaneous resolution is said to occur in 20% to 50% of patients with the disease.24 In this case, surgical removal was not performed due to his advanced dementia and risk of delirium.26 However, all three types of implants can be removed surgically. The intervention suggested by the specialist was mostly successful in minimizing his agitation.

Conclusion

Older adults with dementia and who have penile implants may present challenging clinical scenarios. Unfortunately, the patient’s cognitive status was a significant barrier in completing the workup necessary to assure a more definitive diagnosis. When investigating potential problems with devices in older adults with dementia, a thorough clinical history and physical examination are helpful in identifying the correct source of discomfort. In this case, the first step in the differential diagnosis was ruling out the likelihood of any painful condition and other unmet needs. A detailed history of behaviors from caregivers about possible triggers, the time(s) of occurrence, and any relieving or exacerbating factors should be obtained.27 The caregiver’s knowledge of her husband’s habits and reactions were integral in locating the problem and troubleshooting a solution.

References

1. Dal Bello-Haas VP, Cammer A, Morgan D, Stewart N, Kosteniuk J. Rural and remote dementia care challenges and needs: perspectives of formal and informal care providers residing in Saskatchewan, Canada. Rural Remote Health. 2014;14(3):2747.

2. Harris DP, Chodosh J, Vassar SD, Vickrey BG, Shapiro MF. Primary care providers’ views of challenges and rewards of dementia care relative to other conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(12):2209-2216.

3. Black P. Caring for the patient with a stoma and dementia. Gastrointest Nurs. 2011;9(7):19-24.

4. Trost LW, McCaslin R, Linder B, Hellstrom WJ. Long-term outcomes of penile prostheses for the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2013;10(3):353-366.

5. Lee DJ, Najari BB, Davison WL, et al. Trends in the utilization of penile prostheses in the treatment of erectile dysfunction in the United States. J Sex Med. 2015;12(7):1638-1645.

6. Chung E. Penile prosthesis implant: scientific advances and technological innovations over the last four decades. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6(1):37-45.

7. Montague DK. Penile prosthesis implantation in the era of medical treatment for erectile dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am. 2011;38(2):217-225.

8. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Implanted mechanical/hydraulic urinary continence device - Summary of safety and effectiveness. FDA website. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf/p000053b.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2017.

9. Gofrit ON, Shenfeld OZ, Katz R, Shapiro A, Landau EH, Pode D. Penile prosthesis for erectile dysfunction--long-term follow-up. Harefuah. 2000;139(5-6):183-186, 247.

10. Trost L, Hellstrom WJ. History, contemporary outcomes, and future of penile prostheses:a review of the literature. Sex Med Rev. 2013;1(3):150-163. doi:10.1002/smrj.8

11. Yuhas N, McGowan B, Fontaine T, Czech J, Gambrell-Jones J. Psychosocial interventions for disruptive symptoms of dementia. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2006;44(11):34-42.

12. Norton MJ, Allen RS, Snow AL, et al. Predictors of need-driven behaviors in nursing home residents with dementia and associated certified nursing assistant burden. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(3):303-309.

13. Ahn H, Horgas A. The relationship between pain and disruptive behaviors in nursing home resident with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:14.

14. Gaspar S, Santos Dias J, Martins F, Lopes T. Recent surgical advances in Peyronie’s disease. Acta Med Port. 2016;29(2):131-138.

15. Edwards JL. Diagnosis and management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(10):1403-1410.

16. Roberts RG, Hartlaub PP. Evaluation of dysuria in men. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(3):865-872.

17. Desai AK, Grossberg GT. Recognition and management of behavioral disturbances in dementia. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3(3):93-109.

18. Sood S, James W, Bailon MJ. Priapism associated with atypical antipsychotic medications: a review. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(1):9-17.

19. Sultan Al-Thakafi, Naif Al-Hathal. Peyronie’s disease: a literature review on epidemiology, genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis and work-up. Transl Androl Urol. 2016;5(3):280-289.

20. Pryor JP, Ralph DJ. Clinical presentations of Peyronie’s disease. Int J Impot Res. 2002;14(5): 414-417.

21. Cantoro U, Polito M, Catanzariti F, Montesi L, Lacetera V, Muzzonigro G. Penile plication for Peyronie’s disease: our results with mean follow-up of 103 months on 89 patients. Int J Impot Res. 2014;26(4):156-159.

22. Jalkut M, Gonzalez-Cadavid N, Rajfer J. Peyronie’s disease: a review. Rev Urol. 2003;5(3):142-148.

23. Bettocchi C, Ditonno P, Palumbo F, et al. Penile prosthesis: what should we do about compications? Adv Urol. 2008;2008:573560. doi:10.1155/2008/573560

24. Sharp VJ, Takacs EB, Powell CR. Prostatitis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(4):397-406.

25. Shigehara K, Namiki M. Clinical management of priapism: a review. World J Mens Health. 2016;34(1):1-8.

26. Sadeghi-Nejad H, Ilbeigi P, Wilson SK, et al. Multi-institutional outcome study on the efficacy of closed-suction drainage of the scrotum in three-piece inflatable penile prosthesis surgery. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17(6):535-538.

27. Cohen-Mansfield J. Nonpharmacologic treatment of behavioral disorders in dementia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2013;15(6):765-785.

28. Medsafe: New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority. Medsafe website. https://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/PUArticles/September2014Drug_InducedPriapism.htm. Published September 5, 2014. Accessed October 18, 2017.

29. Eid JF. Types of penile implants. YouTube. https://bit.ly/2zAMXw2. Published March 18, 2015. Accessed October 18, 2017.