Care Transitions From Skilled Nursing Facilities to the Community

Care transitions at the time of hospital discharge have been a subject of intense study in recent years in an effort to reduce adverse events and unnecessary healthcare expenditure. Because patients are discharged from hospitals quicker and sicker, there has been a significant increase in the number of discharges to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). The re-entry to the community after SNF discharge, however, has not received much attention. The author presents a case report of a patient who went through both of these care transitions and avoided potentially dangerous lapses in the continuity of care because of a novel intervention established within the geriatric clinic of the James A. Haley Veterans’ Affairs Hospital in Tampa, FL. This case illustrates the complexity of the processes involved in care coordination at SNF discharge and underscores the need for further studies addressing care transitions for this at-risk population.

Key words: Skilled nursing facility, care transition, hospital discharge, adverse event, readmission.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The growth of hospital medicine in the past decade has resulted in numerous studies evaluating the outcomes of care provided by hospitalists. One recent meta-analysis showed that patients cared for by hospitalists had a significantly shorter length of hospital stay than those cared for by nonhospitalists, with a mean difference of 0.44 days (95% confidence interval, -0.68 to -0.20, P<.001).1 However, it has been postulated that the decrease in length of hospital stays achieved by hospitalists may have increased discharges to other types of healthcare facilities, including skilled nursing facilities (SNFs).2 Over two million Medicare beneficiaries were discharged from hospitals to SNFs in 2009.3 Patients who are discharged to SNFs are often older, medically complex, and functionally impaired.4

Although increased attention has been paid to care transitions surrounding hospital discharge, there is still a paucity of studies examining the SNF discharge process.5-7 In an effort to improve care transitions at the time of SNF discharge, a Post Discharge Clinic (PDC) was developed within the geriatric clinic at James A. Haley Veterans’ Affairs (VA) Hospital in Tampa, FL, in 2009. This clinic provides comprehensive care coordination for patients transitioning from the community SNFs back to the care of their VA primary care providers (PCPs). To exemplify the process, we report the case of an elderly patient who received care coordination interventions through the PDC.

Case Report

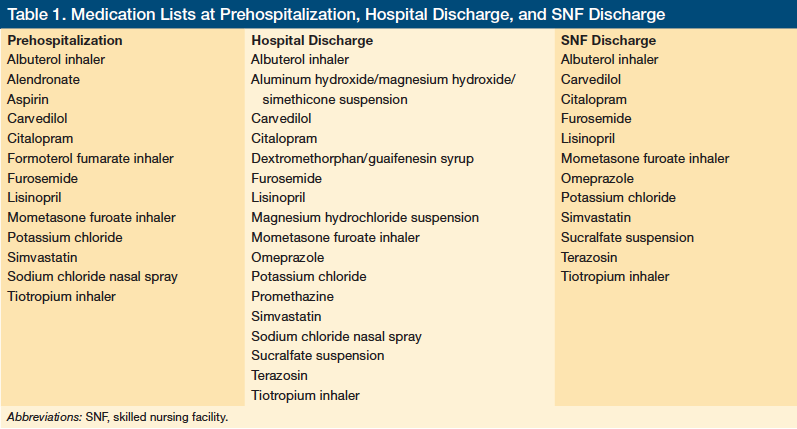

A 75-year-old man was admitted to the hospital for exacerbation of congestive heart failure (CHF). His medical history included atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, osteoporosis, and depression. His medications at the time of admission included alendronate, aspirin, and carvedilol, among many others (Table 1). The patient was treated with intravenous diuretics, with a good response. He underwent thoracentesis of a left-sided pleural effusion, and 900 cc of transudate were removed. An echocardiogram showed a significant decrease in his left ventricular ejection fraction since his previous study from 1 year earlier, and the cardiologist recommended outpatient follow-up to evaluate the feasibility of a left heart catheterization. The patient was discharged to his home after 5 days of hospitalization. One day later, he returned to the hospital because of cough and chills and was readmitted. A diagnosis of healthcare-associated pneumonia was made and he received intravenous antibiotics. During his hospital course, he developed hematochezia, with a drop of 2g/dL in hemoglobin from his prehospitalization baseline level. A colonoscopy revealed patchy colitis, and a mucosal biopsy was performed. The patient’s hematochezia resolved after 2 days without a need for blood transfusion. He was discharged to a community SNF on hospital day 10 for 6 weeks of rehabilitation. Mucosal biopsy results were pending at the time of his admission to the SNF.

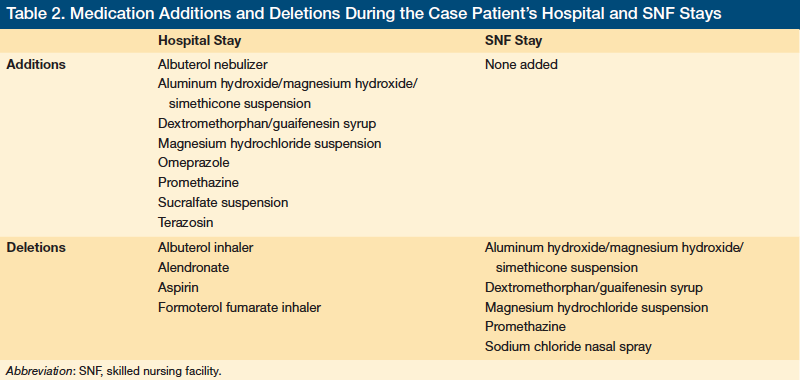

The PDC social worker maintained contact with the SNF for the duration of the patient’s stay and arranged a PDC appointment one day prior to his discharge from the facility. The PDC advanced nurse practitioner obtained the SNF medical records before the appointment and performed medication reconciliation using three medication lists: prehospitalization, hospital discharge, and SNF discharge (Table 1). While comparing the SNF discharge medication list to that of the prehospitalization list, it was noted that four new medications had been started and these were ordered through the VA outpatient pharmacy. In addition, five medications on the prehospitalization list had been discontinued (Table 2). The patient and his son, who acted as his primary caregiver, were educated on the new medication regimen. The electronic medical record was updated and a copy of the medication list was provided to the patient during the visit. The need for medical equipment was assessed via an interview with the patient, a physical examination, and communication with the SNF staff. A reacher, sock aid, blood pressure monitor, and rolling walker were issued at the time of the visit; however, even with the walker, the patient was not able to walk beyond 100 feet, so home physical therapy was arranged by the PDC advanced nurse practitioner to begin on the day after discharge from the SNF. Results of the colon biopsy, which had not been available at the time of hospital discharge, revealed focal active colitis with features suggestive of ischemia, and this was discussed with the patient and his son during the PDC visit.

It was also noted during the PDC visit that the patient had an indwelling urinary drainage catheter. Review of the medical records indicated that it had been placed for acute urinary retention during the patient’s second hospitalization. Information from the SNF staff revealed that removal of the catheter had been attempted during his stay, but without success. It was also noted that the patient had missed the cardiology clinic appointment during his stay at the SNF. The PDC advanced nurse practitioner scheduled PCP follow-up within 2 weeks of his discharge from the SNF. The patient and his son were educated on various healthcare matters concerning the patient, including self-monitoring of the patient’s CHF; warning signs and symptoms of CHF exacerbation; importance of fluid restriction; self-administration of the albuterol nebulizer treatment; self-care of the indwelling urinary drainage catheter; and the importance of post-discharge medical follow-up with the cardiologist and PCP. The following recommendations and notes for the PCP were communicated through the patient’s electronic medical record: (1) the timing for the resumption of aspirin, which was discontinued at the time of the patient’s gastrointestinal bleeding, should be addressed; (2) alendronate, which was omitted from his outpatient medication list upon admission to the hospital, should be resumed during the patient’s return visit to his PCP; (3) an optimal bronchodilator regimen should be implemented, as formoterol fumarate and albuterol inhalers were discontinued during the patient’s hospital course, while albuterol by nebulizer was started during the hospitalization and continued throughout the SNF stay; and (4) a urology referral was made to assess the possibility of removing the indwelling urinary drainage catheter because of the failed attempt at removal by the SNF caregivers.

(Continued on next page)

Discussion

The most common system deficit contributing to adverse events after hospitalization is ineffective communication.8 In a 2007 study by Kripalani and colleagues9 that addressed the deficits in flow of information after individuals were discharged from hospitals to their homes, it was found that the discharge summary was available to the PCP at patients’ first post-discharge visit in only 12% to 34% of cases.

When a patient is discharged from a hospital to an SNF and is placed in the care of a new set of providers, the challenges to the flow of information are even greater. Further modifications in the treatment plan and medication profiles are common in this setting, but are not systematically communicated to the provider who will resume care upon discharge to the community. Of special concern are changes in medications that have been implicated in a high percentage of hospitalizations, such as insulin or warfarin.10,11 In addition, the provider in the SNF may have to follow up on studies performed in the hospital, of which the results are not available at the time of hospital discharge, as in the case patient’s mucosal biopsy results. The outcomes of these onsite or off-site medical studies will then need to be relayed to the downstream provider, who will resume the primary care of the patient after his or her discharge from the SNF. The prescription of appropriate medical equipment and home health services are additional crucial components of a successful return to the community. Finally, cognitive and functional decline, a common complication of acute hospitalizations in older patients, may not have resolved by the time the individual is otherwise ready for discharge from the SNF. Failure to assess potential limitations of the patient’s living environment and social support system could bring unexpected challenges to the patient’s successful re-entry to the community, especially in individuals with cognitive and/or functional impairment.12

Care coordination interventions targeting high-risk populations (eg, older age, multiple comorbidities, recent hospitalization) at the time of hospital discharge have been shown to improve patient safety and reduce rehospitalizations.13,14 There has been increasing recognition of the need to align care between the hospital and the SNF to reduce adverse events and unnecessary hospital use.15-17 The PDC at Tampa VA Hospital was developed as an innovative care model to improve the care transition process for patients who are returning to the community after receiving post-hospitalization skilled care at the community SNF. Prior to implementation of the PDC, individuals discharged from community SNFs depended on the urgent care clinic to obtain medications and medical equipment. Patients were expected to arrange the PCP appointment after their discharge from the SNF. Since it was the responsibility of the patient to complete these tasks, medications and medical equipment were not always collected and PCP appointments were not always scheduled in a timely manner.

Through the innovative PDC program, every patient discharged from the Tampa VA hospital to a community SNF is tracked by the PDC social worker throughout his or her stay at the SNF to ensure timely scheduling of a PDC visit. The patients are seen at the PDC, located in a geriatric clinic, for a one-time visit at the time of SNF discharge. A PDC advanced nurse practitioner, under the guidance of a geriatrician, provides comprehensive care coordination that comprises medication reconciliation, medical equipment provision, home health services, patient and caregiver education, and communication with the PCP via the electronic medical record. With a structured system for tracking and delivering information, the PDC enhances the flow of information between the VA and its community partners, enabling timely and coordinated transition of care that aims to reduce unnecessary emergency healthcare use or rehospitalizations after SNF discharge.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates how patients discharged from acute care hospitals to SNFs are often in need of complex medical follow-ups with more than one provider, which requires time-intensive care coordination and communication among multiple providers. When care involves more than one healthcare organization, without established systems of communication, such as shared electronic medical records, it becomes fragmented and increases the risk of serious errors. Care coordination interventions targeting high-risk populations (eg, elders, persons with multiple comorbidities, individuals with recent hospitalizations) at the time of hospital discharge have been shown to improve patient safety and reduce rehospitalizations. There has been increasing recognition of the need to align care between the hospital and the SNF to reduce unnecessary hospital use. This case demonstrates the need for further study of SNF discharge processes to improve care transitions from SNFs to the community.

References

1. Rachoin JS, Skaf J, Cerceo E, et al. The impact of hospitalists on length of stay and costs: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(1):

e23-e30.

2. Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. Association of hospitalist care with medical utilization after discharge: evidence of cost shift from a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):152-159.

3. Medicare & Medicaid Statistical Supplement. Centers For Medicare & Medicaid Services Website. www.cms.gov/MedicareMedicaidStatSupp. Updated July 5, 2012. Accessed September 4, 2012.

4. Mason SE, Auerbach C, LaPorte HH. From hospital to nursing facility: factors influencing decisions. Health Soc Work. 2009;34(1):8-15.

5. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822-1828.

6. Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al; American College of Physicians; Society of General Internal Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; American Geriatrics Society; American College of Emergency Physicians; Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. Transitions of care consensus policy statement American College of Physicians-Society of General Internal Medicine-Society of Hospital Medicine-American Geriatrics Society-American College of Emergency Physicians-Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971-976.

7. Boling PA, Parsons P. A research and policy agenda for transitions from nursing homes to home. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2007;26(4):121-131.

8. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167.

9. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841.

10. Budnitz DS, Shehab N, Kegler SR, Richards CL. Medication use leading to emergency department visits for adverse drug events in older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(11):755-765.

11. Hanlon JT, Pieper CF, Hajjar ER, et al. Incidence and predictors of all and preventable adverse drug reactions in frail elderly persons after hospital stay. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(5):511-515.

12. Cole MG. Persistent delirium in older hospital patients. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23(3):250-254.

13. Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):

178-187.

14. Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281(7):613-620.

15. Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Tappen R, et al. Interventions to reduce hospitalizations from nursing homes: evaluation of the INTERACT II collaborative quality improvement project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):745-753.

16. Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(1):57-64.

17. Tjia J, Bonner A, Briesacher BA, et al. Medication discrepancies upon hospital to skilled nursing facility transitions. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(5):630-635.

Disclosure:

The author reports no relevant financial relationships.

Acknowledgments:

The Post Discharge Clinic is a pilot project funded by the Veterans Health Administration, Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care. The funding organization had no role in the preparation of this case report. The author would like to thank Claudia Beghe, MD, for her guidance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Address correspondence to:

Hae K. Park, MD

James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital

13000 Bruce B. Downs Blvd

Tampa, FL 33612

hae-kyoung.park@va.gov