Care Transitions–It’s Not the Transition, It’s the Care

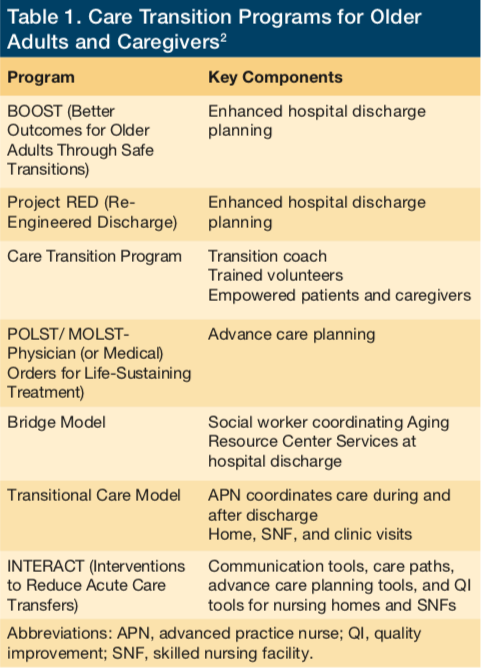

With all of the focus on care transitions, what has been missing is the fact that the care period before the transition provides an opportunity to prepare the patient for success once they are home. Unfortunately, all too often, the inpatient care period is solely focused on dealing with acute care situations with no foresight into what will be needed for success at home. Even after years of seeing the development of many care transition programs (Table 1), patient outcomes remain lackluster. I personally experienced a transition failure several years ago, which I chronicled in the Journal of the American Geriatric Society.1 As a practicing geriatrician, almost daily I witness continued failure in care transitions for my frail, older adult patients.

One reason that care transitions often fail is that, during the inpatient facility (hospital and skilled nursing facility)–based care period, the focus is typically on shortening the length of stay rather than preparing patients to succeed in remaining healthy outside the health care facility. This is directly related to how facility-based care has traditionally been reimbursed, with the facility being paid one lump sum for all of the facility-based care, including the costs of room and board, nursing care, and treatments. This reimbursement would usually be the same regardless of the length of stay, fostering behavior focused on ever-shortening of the stay. For example, if an older adult was admitted for uncontrolled atrial fibrillation requiring rate control and anticoagulation, that hospital could be reimbursed $7000 for that stay. Those hospitals able to shorten the length of stay for this patient would benefit from greater profits, or “excess revenue” as it is referred to for nonprofit facilities.

Of course, the reimbursement world is shifting from this narrow volume-based payment system to one in which payment is tied to performance. This pay-for-performance system is causing facilities to look at care more broadly. This broader view means that facilities are becoming responsible for more than just services as well as for care provided outside of the facility. Under this new system, facilities will become less focused on shortening length of stay and more focused on their ability to have a positive impact on a patient’s care needs over a much longer period of time. Facilities can benefit from establishing a plan of care that can best ensure their success outside the facility. Some of the programs available to promote success include improved medication management, caregiver support, and providing appropriate end-of-life care.

Medication Management

There are several opportunities to improve medication management during the inpatient care period. This begins with medication reconciliation. Many may think that medication reconciliation does not occur until after the inpatient stay, but, in fact, successful medication reconciliation begins upon admission and continues through the inpatient stay.

Typically, medications used in the inpatient setting are only those specific for that setting rather than what will be best for that patient in the outpatient setting. Many patients are discharged without being transitioned to the medication regimen that has better patient success in the outpatient setting. An example of this is continuing the use of sliding scale insulin rather than establishing a basal bolus insulin treatment. The result is a lost opportunity, or worse, a situation where patients fail the transition to an outpatient regimen.

By using the inpatient stay as an opportunity to establish the “best” outpatient medication regimen, patients could have more successful health outcomes, resulting in fewer hospitalizations. Part of establishing the best medication regimen includes ensuring that patients can adhere to their treatment plans. This is also true for patient management of medical devices. The usual course in the inpatient setting is to use devices that are health care provider delivered, such as nebulized medications or injectables. Patients are typically not allowed or instructed to use such devices themselves; this can prevent them from successfully managing their care in the outpatient setting. Facilities should instead use this time to train patients in self-management in order to prepare them for greater success at independent medication management. Imagine the number of failures that occur each and every day because older adults with impairments are provided a handful of scripts along with verbal instructions as they are being discharged rather than undergoing regular education throughout their inpatient stay.

This focus on using the inpatient stay to establish the best plan of care may require extra time, and, with a focus on reducing length of stay, this could be viewed negatively. However, with a shift to value-based reimbursement, where facilities are also responsible for the care of their patients beyond their walls, this new view has tremendous value.

Caregiver Support

One of the most effective resources in keeping an older adult safe in the community is their caregiver. Yet, despite this, caregivers are often viewed as an intrusion to facility-based care. Typically caregivers are only engaged at the time of discharge and are given curt direction, usually devoid of specifics or an opportunity for the caregiver to ask questions because these may delay the discharge process.

With a new focus on reducing readmissions, time during the facility care period would be well spent engaging and arming each caregiver with the knowledge to assist their loved one in managing their care successfully outside of the health care facility. Resources on providing this training and other tools for caregivers could have a tremendous yield in improving outcomes, especially for frail older adults who are reliant on their caregivers for support. Caregivers with the proper training can assist patients with everything from managing their conditions through early identification of failures to proper medication management and scheduling timely physician follow-up.

End-of-Life Care

With a shortsighted view that is simply focused on what is needed here and now during the facility care period, discussions and planning around end-of-life preferences are often missed. Because end-of-life care discussions can lead to the patient avoiding further facility-based care, facilities may receive decreased reimbursement when care is based on service volume. Investing resources to decrease revenue is most often avoided as bad business. However, in contrast, when the facility is being reimbursed based on value and thus is responsible for decreasing the total cost of care, investing to promote end-of-life discussions can have sizable returns.

For example, the hospital team, which includes those with palliative care expertise, can help Mrs M, a 92-year-old woman with congestive heart failure, to avoid repeated hospital admissions by taking the time to provide information to her regarding her condition and, most importantly, listening to her wishes for her end-of-life care. Although this type of conversation is best completed outside of an acute care situation, having an end-of-life care conversation at each and every opportunity, including during an inpatient stay, can ensure that the patient’s wishes are fully understood and followed.

A Unit for Care

To be most effective under this new reimbursement system, the current fragmented system—designed more for provider ease than for patient needs—must shift its focus to being patient-centered. Although we speak often about patient-centered care, most facility-based care is designed with providers in mind. Things such as double rooms, nursing stations, hospitalist programs, and visiting hours are all the result of a provider-focused system.

Take the typical hospitalist program, for example. Admissions are usually based on a simple rotation system in order to evenly allocate work assignments. Also, hospitalists are more typically assigned based on the floor rather than the patient. The result is that, when Mrs J is admitted, she is assigned to Dr A because she was next up for the admission. However, once admitted, Mrs J could be attended to by Drs B, C, and D as she moves from the intensive care unit, progressive care unit, and general medical floor. On discharge, these hospitalists may not communicate effectively with Mrs J’s primary care provider (PCP) in the community. Worst yet, if because of a poor transition Mrs J fails in the community, resulting in a readmission, it could be Dr E handling the readmission, followed by a new list of hospitalists.

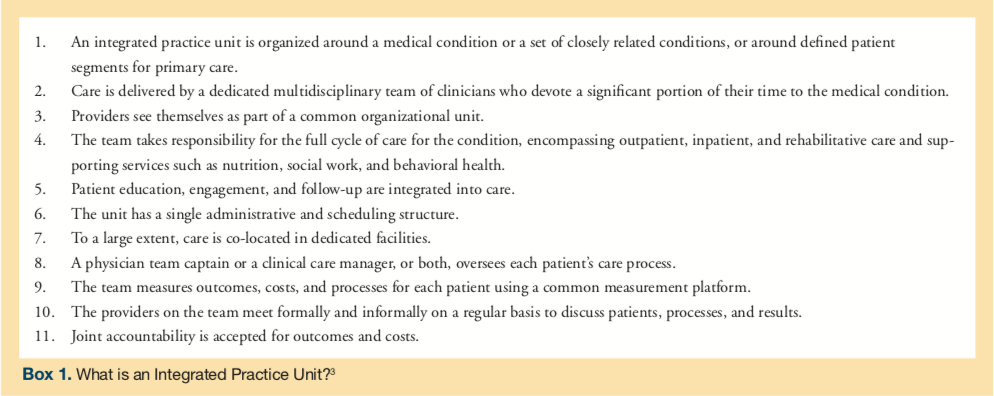

Instead, picture an integrated practice unit (IPU) that is dedicated to Mrs J. This unit would be staffed by a team of both clinical and nonclinical personnel, potentially including a dedicated hospitalist, pharmacist, social worker, case and care manager, and PCP all working together (Box 1). Now, Mrs J has a team that is responsible for her on every admission, working in sync with her community team such that medication management, caregiver support, and appropriate end-of-life care are all efficiently and effectively delivered.

When care transition is simply layered on top of a fragmented and dysfunctional delivery system, outcomes have been described as modest at best. Instead, when coordination takes place organically in IPUs, substantial outcomes have been realized.

Providers working together in an IPU within health care facilities and beyond would be well-served by improving the care they provide to ensure success in keeping patients healthy and preventing them from returning to the facility for care. With less focus on the transition and a greater focus on the care, health care facility transitions can become more patient-centered.

1. Stefanacci RG. Lost in Transition. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(12):2369-2370.

2. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Administration on Aging. Transitions and long-term care: Reducing preventable hospital readmissions among nursing facility residents. acl.gov Web site. http://www.acl.gov. Accessed July 29, 2016.

3. Porter ME, Lee TH. The strategy that will fix health care. Harvard Business Review. October 2013.