Care Access and the Shift to Value-Based Care in LTC

While the fate of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act still hangs in the balance, the likely impact on long-term care (LTC) patients and providers is becoming increasingly clear. Perhaps the biggest concerns at hand are access to care and the shift to value-based payment instead of fee-for-service. These changes in access mean, on the insurance side, that patients will be more likely to enter Medicare after a lengthy period of being uninsured. It also means that fewer Medicare beneficiaries will be covered by Medicaid. But the issue of access also applies to patient access to appropriate care, which may be difficult as access to specialists becomes restricted and primary care providers take on a greater role in providing specialty care In addition, the shift to value-based payment means LTC providers need to start focusing on factors outside of the traditional health care setting in order to deliver on the clinical and financial outcomes that are required for accountable care organizations.

Limited Provider Access

Current Medicare beneficiaries are going to be cared for by providers operating under the new Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) value-based programs. Given the complexity of these programs, many providers may choose to drop out of the Medicare program and take the penalty rather than invest in the systems needed to deliver on MACRA’s accountable outcomes. The result will be fewer providers available for Medicare beneficiaries. LTC providers left to care for these older adults will need to adjust to take into account care access restrictions, as primary care providers will be called upon to perform in the face of an ever-declining number of specialists and other primary care providers.

Deferred Maintenance

With the certain reduction in number of providers and rising cost of individual insurance coverage through reductions in Health Insurance Marketplace offerings, many pre-Medicare individuals will be uninsured or, at best, underinsured. Thus, they may forgo needed chronic care management and preventive care, resulting in their entering the Medicare program in need of immediate care (Table 1).

The Initial Preventive Physical Examination (IPPE), also known as the “Welcome to Medicare Preventive Visit,” is available to the 10,000 new Medicare beneficiaries entering Medicare daily, which equals approximately 3,650,000. The goals of the IPPE are health promotion, disease prevention, and detection. Medicare pays for one IPPE per beneficiary per lifetime for beneficiaries within the first 12 months of the effective date of the beneficiary’s first Medicare Part B coverage period. This deferred care, due to a lack of insurance coverage just prior to coming into Medicare, will impact LTC providers utilizing the IPPE, as providers will need to be prepared to help Medicare beneficiaries work through deferred care issues to deliver on the outcomes they are being held accountable for under value-based care system, such as vaccination completion and diabetes outcomes such as hemoglobin A1c.

Decline of Institutional Care

The expected shift of federal funding from Medicaid beneficiaries to States to block grants will reduce the federal contribution, resulting in a decrease in the number and coverage of Medicaid patients. This means that Medicare beneficiaries who are currently covered by Medicare and Medicaid will lose this dual coverage, making them responsible for not only the 20% out-of-pocket costs for most services that Medicare does not cover but the much bigger cost of long-stay skilled nursing care. As a result, there will be a decline in traditional, long-term, institutional care for less expensive home- and community-based LTC, such as adult daycare and home-based services. LTC providers that are based in skilled-nursing facilities will see their facilities caring for more and more short-stay patients that look like hospital patients, while the traditional nursing home (NH) patient will be increasingly cared for in the community.

Social Determinants of Health

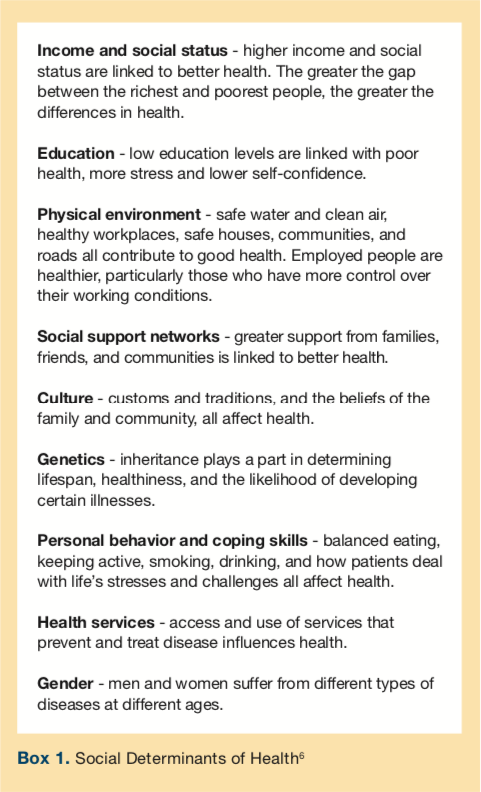

The shift of focus to value-based outcomes for LTC providers requires addressing nontraditional health care factors such as the social determinants of health (Box 1). The social determinants of health, which are a critical component of care, especially for frail older adults, was highlighted in the Healthy People 2020 initiative from the federal government and is a foundation of the Triple Aim. In brief, health is determined, in part, by access to social and economic opportunities; the resources and supports available in our homes, neighborhoods, and communities; the quality of our schooling; the safety of our workplaces; the cleanliness of our water, food, and air; and the nature of our social interactions and relationships. The inclusion of social determinants of health begins in our patients’ homes, schools, workplaces, neighborhoods, communities, and thus, by extension, should be a consideration in LTC institutions.

In the Healthy People 2020 report,1 the government points out that these social and physical determinants of health impact a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes. Moreover, social and physical determinants of health are often the result of decisions made at the higher levels of society. Belief in the importance of social determinants of health is shared by the World Health Organization, evident from a 2008 report published by their Commission on Social Determinants of Health,2 as well as by other US health initiatives such as the National Partnership for Action to End Health Disparities,3,4 and the National Prevention and Health Promotion Strategy.5

The Healthy People 2020 report also provides recommendations for how to address the social determinants of health by including the suggestion to “Create social and physical environments that promote good health for all” as one of the four overarching goals for the decade.1 These factors need to be taken into account by LTC providers to achieve optimum health outcomes.

In the end, LTC providers will face an increasing complex environment, far from the world of volume-based care delivery in a traditional NH setting where payment is simply based on the number of residents seen. Rather, the future for LTC providers will mean doing much more to deliver improved clinical and financial outcomes for LTC patients much further outside their historic scope of services and traditional setting in order to be successful.

References

1. Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020. Healthy People 2020: An Opportunity to Address the Societal Determinants of Health in the United States. US HHS website. https://www.healthypeople.gov/ 2010/hp2020/advisory/SocietalDeterminantsHealth.htm. Published July 26, 2010. Accessed July 27, 2017.

2. World Health Organization. Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Wolrd Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/en. Accessed July 27, 2017.

3. National Partnership for Action. HHS Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. National Partnership for Action website. https://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlid=10. Published 2011. Accessed July 27, 2017.

4. National Partnership for Action. The National Stakeholder Strategy for Achieving Health Equity. National Partnership for Action website. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/npa/templates/content.aspx?lvl=1&lvlid=33&ID=286. Published 2011. Accessed July 27, 2017.

5. The National Prevention Council. The National Prevention Strategy: America’s Plan for Better Health and Wellness. Surgeon General website. https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/priorities/prevention/strategy/report.pdf. Published June 2011. Accessed July 27, 2017.

6. World Health Organization. Health Impact Assessment (HIA): the determinants of health. WHO website. https://www.who.int/hia/evidence/doh/en/. Accessed July 27, 2017.