Breathing Easier: Pulmonary Management in Long-Term Care

Just as breathing is a vital function for long-term care (LTC) residents, good pulmonary management is vital to the LTC facility. Two of the five Medicare hospital readmission penalties are related to the quality of pulmonary management; when patients who are hospitalized for both pneumonia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are hospitalized in less than 30 days, the initial hospital is penalized.1 Additionally, four of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) skilled-nursing facility (SNF) quality measures focus on pulmonary vaccinations.2 Finally, the focus of CMS on antibiotic stewardship requires appropriate pulmonary management, because antibiotic treatment for viral infections or development of a potentially preventable bacterial pulmonary infection is increasingly being viewed negatively for facilities. For all of these reasons and more, appropriate pulmonary management is vital for patients and SNFs alike.

To prevent pulmonary illnesses among LTC residents, it is critical to provide efficient and effective diagnosis and treatment for COPD, vaccination programs to prevent pulmonary infections, and antibiotic stewardship programs. These efforts can be facilitated by the presence of a facility-based respiratory therapist.

Diagnosis and Treatment of COPD

COPD, a diagnosis that is given to 15% of LTC residents,3 is a significant and growing problem. Among patients with COPD who are hospitalized, mortality rates are 11%, and survivors of a first hospitalization have a 50% chance of rehospitalization within 6 months.4 For every 10% decrease in FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in 1 second), cardiovascular mortality increases by almost 30%, and non-fatal coronary events increase by ~20%.5 This high hospitalization rate for patients with COPD has lead CMS to add it to the list of diagnoses for which hospitals are now accountable for reducing readmissions.1

COPD is usually a progressive illness characterized by persistent airflow obstruction with a significant inflammatory component. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) has provided a consensus report, titled Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD, which was first published in 2011 and was last updated in January 2015.6 Nursing staff will be best prepared to care for residents with COPD by understanding these GOLD criteria.

In patients with COPD, exhalation takes longer and requires greater effort. Spirometry is required to measure the extent of airway obstruction; however, spirometry measurements for SNF residents are often lacking. Even in patients who are frequently hospitalized, spirometry is often not done during an acute hospitalization because these measurements would be outside of the reference range.6 Also, it may be difficult for individuals with dementia to follow instructions adequately for successful spirometry testing. Finally, spirometry may be inadequate for diagnosing COPD in older former smokers, according to recent findings.7

Instead, diagnosis of COPD can be done through other means. Airway obstruction can be identified by asking a resident to exhale like they are blowing out birthday candles while osculating the lungs, which will produce an expiratory wheeze in those with COPD. Also, this expiratory will be more prolonged in a resident with COPD than in a resident with normal pulmonary function.

GOLD defines a COPD exacerbation as “an acute recent event characterized by the worsening of the patient’s respiratory symptoms that is beyond normal day-to-day variations and leads to a change in medication.”6 Symptoms of a COPD exacerbation include increased shortness of breath, cough, and sputum production. Expert man-agement of exacerbations is critically important, because the residents’ health status is compromised, potentially leading to complications associated with hospitalization. Exacerbations are also associated with the largest cost involved in the management of COPD. SNF staff needs to monitor residents for the developments of symptoms and work as a team with related health care professionals. Exacerbations can make decline in lung function worse, and a resident may need several weeks to recover from an acute episode.

The GOLD criteria use a number of questionnaires as tools to evaluate status, severity, and exacerbation of COPD. Four categories based on patient risk for symptoms and exacerbations have been established (categories A–D). A portion of the GOLD classification is based on the COPD Assessment Test (CAT).6 The CAT is a validated, short (8-question) questionnaire that can be used to evaluate the status and severity of COPD along with exacerbations. The 8 items include cough, chest mucus, chest tightness, shortness of breath while walking uphill, limitations with house activities, comfort leaving home, sleeps deeply, energy level.

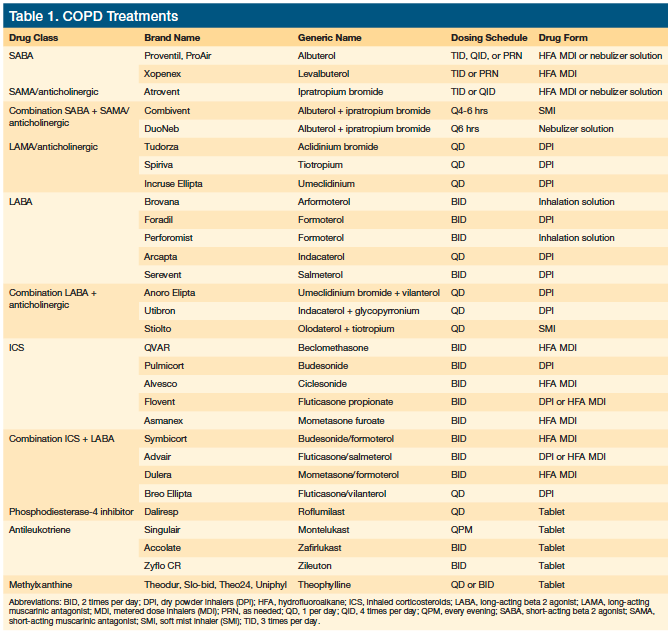

With COPD, the primary focus is on reduction of symptoms and risk, improving exercise tolerance, and improving health status.6 Multiple medications are available for management of residents with COPD (Table 1), based on GOLD categories A–D. Metered dose inhalers (MDIs) are often used by SNF residents; however, there is substantial evidence that they are ineffective for residents in LTC settings.8,9 Successful use of an MDI requires coordination between a forced inhalation and compression of the canister. Chronic comorbid conditions often present in SNF residents, such as arthritis, cognitive impairment, weak inhalations, and issues with coordination, that make successful use of an MDI challenging.

One study assessed the MDI technique of 30 older patients (mean age, 79.9 years).8 Sixty percent were competent, though only 10% had an ideal technique; 40% were incompetent. Inadequate timing of actuation and inhalation was the most frequent error made. Competence was significantly related to mental status questionnaire (MSQ) scores of 7 out of 10 or higher. Patients who were first prescribed an MDI in hospital were significantly more likely to be competent than those prescribed an MDI by the general practitioner. Competence was not related to age, underlying diagnosis, or duration of MDI therapy. Elderly patients should be carefully selected and properly instructed by the prescribing doctor.

Previous systematic reviews in COPD patients found similar clinical outcomes for drugs delivered by handheld inhalers, such as pressurized metered dose inhalers (pMDIs), dry powder inhalers (DPIs), and nebulizers, provided that the devices were used correctly.9 However, in routine clinical practice, critical errors in using handheld inhalers are highly prevalent and frequently result in inadequate symptom relief. In comparison with pMDIs and DPIs, effective drug delivery with conventional pneumatic nebulizers requires less intensive patient training. Moreover, by design, newer nebulizers are more portable and more efficient than traditional jet nebulizers. The current body of evidence regarding nebulizer use for maintenance therapy in patients with moderate to severe COPD, including use during exacerbations, suggests that the efficacy of long-term nebulizer therapy is similar, and in some respects superior, to that with pMDIs or DPIs.9 Therefore, despite several known drawbacks associated with nebulizer therapy, maintenance therapy with nebulizers should be employed in elderly patients, those with severe disease and frequent exacerbations, and those with physical and/or cognitive limitations.

Corticosteroids such as prednisone are frequently used for COPD exacerbations and are extremely helpful to reduce inflammation.10 When corticosteroids are used for acute exacerbations, they should only be used for short periods of time. Monitoring should include watching for swelling, changes in mood, muscle pain, and hyperglycemia, especially in the diabetic resident. SNF staff must ensure that older adult COPD patients are actually getting their prescribed medications. This requires observation, training, and appropriate use of the correct delivery mechanism for getting these important medications to their residents. Nursing staff also plays a key role in ensuring that patients are optimizing therapy as well as not using medications meant for regular maintenance as required for rescue treatments. A critical component of the interdisciplinary team for pulmonary management is the respiratory therapist. Respiratory therapists care for residents who have trouble breathing, working closely with speech therapists and occupational therapists.

In the ideal situation, COPD exacerbations can be handled in the LTC setting. However, the GOLD guidelines present the following potential indications for hospital assessment or admission:6 (1) marked increase in intensity of symptoms, such as

sudden development of resting dyspnea; (2) severe underlying COPD; (3) onset of new physical signs (eg, cyanosis, peripheral edema); (4) failure of an exacerbation to respond to initial medical management; (5) presence of serious comorbidities (eg, heart failure or newly occurring arrhythmias); (6) frequent exacerbations; (7) older age; and (8) insufficient home support.

Vaccination Against Pulmonary Infections

Prevention of pulmonary diseases through effective facility-based vaccination programs for both influenza and pneumococcal infections is another important component of successful pulmonary management in LTC.11

All persons aged >50 years are recommended to be vaccinated to prevent influenza.12 This is particularly important for persons who are at increased risk for severe complications from influenza, or at higher risk for influenza-related outpatient, emergency department, or hospital visits, which is the case for most if not all long-term care residents. Influenza vaccine should be administered as soon as it becomes available. Because studies show that protection appears to last throughout the influenza season, August or September is not too early to administer the vaccine.12 Waiting to give the vaccine only increases the risk of missed vaccinations. The vaccine should also be given throughout the entire season, because influenza occurs through May and June. A rule of thumb would be to continue to give the vaccine until it expires (typically in June).

The high-dose influenza vaccine contains four times the amount of antigen contained in regular influenza shots.13 The rationale for using this vaccine is that the higher dose would be more effective in older patients. The downsides, however, are an increase in injection sites reactions and a higher cost. Some facilities use the high-dose vaccine on the basis of evidence suggesting its superiority; however, neither the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) nor the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has expressed a preference for one vaccine over another at this time.12,14

Two pneumococcal vaccines are currently licensed for use in the United States: the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) and the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). The recommended intervals between PCV13 and PPSV23 given in series differ by age and risk group and the order in which the two vaccines are given. The ACIP currently recommends that a dose of PCV13 be followed by a dose of PPSV23 in all adults aged ≥65 years who have not previously received pneumococcal vaccine and in persons aged ≥2 years who are at high risk for pneu-mococcal disease because of underlying medical conditions.15

In August 2014, ACIP recommended routine use of a dose of PCV13 followed by a dose of PPSV23 given 6–12 months later among immunocompetent adults aged ≥65 years. Adults aged ≥65 years with immunocompromising conditions, functional or anatomic asplenia, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks, or cochlear implants are recommended to receive PCV13 first followed by PPSV23 ≥8 weeks later. ACIP also recommended that all adults aged ≥65 years who already received PPSV23 receive a dose of PCV13 ≥1 year later (PPSV23–PCV13 sequence).16

The difference in the recommended interval depending on the order in which the two vaccines were given added significant complexity and created implementation challenges for this age group. To simplify the recommendations, on June 25, 2015, ACIP changed the recommended interval between PCV13 followed by PPSV23 (PCV13–PPSV23 sequence) from 6–12 months to ≥1 year for immunocompetent adults aged ≥65 years.16 Recommended intervals for all other age and risk groups remain unchanged.16

Efficient and effective facility vaccination requires that a process be in place. For pneumococcal vaccination, this process should occur with a review of the immunization status of all current residents and all newly admitted residents upon admission. Additionally, a facility-wide annual review should be done during the annual influenza season. This process should adhere to the following steps. First, the resident’s age must be determined, because the vaccine schedule for immunocompetent individuals aged 65 years and older and those between 50 and 65 years of age differ. Next, one must determine whether the resident has ever been vaccinated, and, if so, when and with what vaccine. Having a developed, detailed review process will ensure that all residents are appropriately vaccinated in order to prevent avoidable infections.

Antibiotic Stewardship

Also critical to good pulmonary management is antibiotic stewardship to ensure the appropriate use of antibiotics. Millions of people are prescribed antibiotics each year for viral infections and conditions such as positive non-infectious urinary cultures and sinusitis that are actually complications of the common cold, hay fever, or allergies, rather than actual bacterial respiratory illnesses. In fact, a significant percentage of all antibiotic prescriptions for adults in outpatient care are for viruses and other non-bacterial infections or conditions.17 The CDC has stated that overprescribing and misprescribing of antibiotics is contributing to the growing challenges posed by antibiotic-resistant bacteria.18 Studies demonstrate that improving prescribing practices in health care settings can not only help reduce rates of antibiotic resistance and Clostridium difficile infection but also improve individual patient outcomes, all while reducing health care costs.18

LTC facilities increasingly are being cited for inappropriate antibiotic use. A significant percentage of antibiotics prescribed in facilities have been found to be unnecessary or inappropriate. In fact, in SNFs, the inappropriate use of antibiotics has a specific guideline (F-Tag 329 Unnecessary Drugs).19

To help curb this problem, the CDC has recommended a more facility-based approach to antibiotic stewardship programs.20 The CDC has directed health care providers to improve antibiotic use by prescribing antibiotics correctly, starting the right drug promptly at the right dose for the right duration, reassessing the prescription within 48 hours based on tests and patient exam, documenting the dose, duration, and indication for every antibiotic prescription, and staying aware of antibiotic resistance patterns in your facility.21 The CDC has similar recommendations for the treatment of pneumonia.21 Through these efforts and others, including the addition of an Infectious Prevention and Control Officer, more appropriate use of antibiotics in SNFs can be achieved.

Conclusion

Successful pulmonary management in long-term care requires an interdisciplinary team, often including a respiratory therapist. SNFs that adequately manage their residents’ pulmonary conditions are able to attract a greater number of sub-acute pulmonary patients from area hospitals. These hospitals are willing to increase their referrals to these SNFs because of the ability to decrease their acute inpatient length of stay (LOS) and readmission rates for these high-risk patients. The result is hospitals realize a shortened LOS for pulmonary patients and decreased readmission rate while SNFs see an increase in their sub-acute census. Of course, the real benefit is borne by residents who benefit from intensive pulmonary management services, allowing them to breathe a little bit easier.

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Pro-gram (HRRP). CMS website. Accessed March 7, 2016.

2. RTI International. MDS 3.0 Quality Measures: User’s Manual. (v9.0 08-15-2015). Effective October 1, 2015. Accessed March 7, 2016.

3. Pleasants RA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in long-term care. Annals of Long-Term Care. 2009;17(3). http://www.annalsoflongtermcare.com/content/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-long-term-care. Accessed March 7, 2016.

4. ADAM Inc. In-depth report: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The New York Times. Reviewed May 23, 2013. Accessed March 7, 2016.

5. Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Enright PL, Manfreda J. Hospitalizations and mortality in the Lung Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:333–339.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary dis-ease. Updated January 2015. GOLD COPD website. Accessed March 7, 2016.

8. Barreiro TJ, Perillo I. An approach to interpreting spirometry. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(5):1107-1115.

9. Allen SC, Prior A. What determines whether an elderly patient can use a metered dose inhaler correctly? Br J Dis Chest. 80(1):45-49.

10. Dhand R, Dolovich M, Chipps B, Myers TR, Restrepo R, Farrar JR. The role of nebulized therapy in the management of COPD: evidence and recommendations. COPD. 2012;9(1):58-72.

11. Mayo Clinic Staff. Diseases and Conditions: COPD. Treatment and drugs. Mayo Clinic website. Accessed March 7, 2016.

12. Stefanacci RG, Haimowitz D. Giving older adults a shot. Geriatric Nursing. 2014;35:386-391.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccination: who should do it, who should not and who should take precautions. CDC website. Updated November 4, 2015. Accessed March 7, 2016.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fluzone high-dose seasonal influenza vaccine. CDC website. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/protect/vaccine/qa_fluzone.htm. Updated August 19, 2015. Accessed March 7, 2016.

15. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Olsen SJ, et al. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2015-16 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64(30):818-825.

16. Kobayashi M, Bennett NM, Gierke R, et al. Intervals between PCV13 and PPSV23 vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(34):944-947.

17. Tomczyk S, Bennett NM, Stoecker C, et al. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal con-jugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among adults aged ≥65 years: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Prac-tices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:822–825.

18. Stefanacci RG, Haimowitz D. Bigger than ebola. Geriatric Nursing. 2015;36:61-64.

19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Get smart for healthcare. CDC website. http://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/healthcare/. Accessed March 7, 2016.

20. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS Manual Sustem Pub. 100-07 State Operations Provider Certification Transmittal 22. Subject Revisions to Appendix P and PP. CMS website. Published December 15, 2006. Accessed March 7, 2016.

21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Checklist for core elements of hospital antibiotic stewardship programs. CDC website. Accessed March 7, 2016.