The Biggest Wound: Oral Health in Long-Term Care Residents

Poor oral hygiene has been associated with many diseases, including cardiovascular diseases such as stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, respiratory ailments such as pneumonia, and periodontal disease. In long-term care (LTC) facilities, residents often need help with oral care, but rarely receive it. When help is provided, it generally comes from nursing assistants, who often do not have proper training on managing oral health issues in dependent adults and do not know the importance of proper oral hygiene in this population. In nursing assistant textbooks, which are generally written by nurses without input from dental hygienists, oral care discussions are relegated to sections on cosmetic care and often make unrealistic recommendations. In this article, the author provides a review of the structures of the tooth and gums; discusses periodontal disease and its implications; makes recommendations to improve the textbooks for nursing assistants, such as by moving oral care into its own chapter; and discusses the role of the dental hygienist in improving the oral and overall health of LTC residents.

Over the last 15 years, evidence demonstrating the mouth as the missing link to better health has been mounting. A study by Emory University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that people who floss their teeth daily live an average of 6.4 years longer than those who do not.1 Flossing eliminates bacteria, which can cause infections and periodontal disease, both of which can contribute to conditions that result in considerable morbidity and mortality. While some people go to great pains and expense to maintain their oral health, allowing them to keep their teeth longer, oral health maintenance becomes increasingly challenging and less of a priority among the elderly.

In long-term care (LTC) facilities, oral care receives relatively little attention, and as oral hygiene languishes, problems start to occur. This article provides an overview of the oral cavity and includes a short lesson on the effects of oral health on the body. This is a lesson that the dental and medical fields are currently relearning. For quite some time, dentistry has focused on restoring the function of teeth, forgetting in the process that dentistry is actually a medical specialty. The article also makes recommendations to improve the textbooks for nursing assistants, who are often charged with managing the oral health of LTC residents, and discusses the need for more involvement from dental hygienists in the LTC setting.

Examining the Oral Cavity

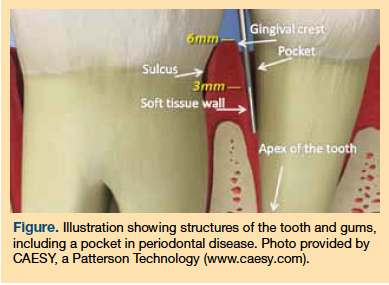

The tooth has many unique structures. The gums, also known as gingiva, have a keratinized outer surface and an epithelium that migrates apically before it attaches to the tooth, leaving unprotected epithelium directly adjacent to the tooth. The gingival sulcus is a moat-like structure around each tooth. In healthy individuals, it is pink and stippled and has a depth of 1 mm to 3 mm. The gingival sulcus fights off pathogens and neutralizes oral biofilm through an inflammatory cascade, but the harder the tissue has to work to remain healthy, the more the sulcus begins to break down. The collagen fibers anchoring the tooth to the bone become weakened by the chemistry of the biofilm in the sulcus and the inflammatory cytokines and enzymes released in response to the biofilm. Collagenase, gelatinase, elastase, protease, and other enzymes manufactured by the inflammatory system weaken the periodontal fibers in an effort to eliminate the infected part of the body, which in this case is the tooth.

In the space between the teeth and gums—known as the sulcus in healthy individuals or a pocket in those with periodontal disease—a cesspool of activity occurs (Figure). Benign Actinomyces and Streptococcus bacteria colonize the biofilm and cover themselves with a protective sticky coating consisting of polysaccharides manufactured from the host-ingested sucrose. As the protected mass of bacteria grows, bacterial pathogens, viruses, and yeast are invited in and the biofilm society begins to thrive. As sociobiological activities start to take place, DNA shifting occurs and new phenotypes emerge in response to the dynamic environment. Eventually toxins are excreted from the biofilm, which is now acting like its own organism.

Histamines, cytotoxins, and other toxins in the sulcular space increase permeability of the epithelium on the soft tissue wall of the sulcus. The topical chemistry and inflammatory response increase the depth of the sulcus by breaking down the bone and attachment fibers, creating a periodontal pocket. It is commonly thought that biofilm grows only on the surface of the tooth and works its way apically, but wound care nurses know firsthand that biofilm also grows on nonkeratinized epithelium. This missing link between dentistry and medicine is going to help provide answers on how to prevent and treat many ailments that currently have a poor prognosis.

Consequences of Periodontal Disease

While the surface area of the soft tissue wall of a periodontally involved pocket in a person with moderate periodontal disease (pockets ≤5 mm) may seem small, it is the equivalent of having an open wound the size of an adult’s palm or a wound that is nearly 1% of the total body surface area.2 A wound of this magnitude occurring anywhere else on the body would promptly be treated, yet periodontal disease remains largely unrecognized by medical practitioners. Even more disconcerting is that this open wound is covered by an active biofilm, which has considerable potential to cause harm.

As periodontal tissue dies, volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) are released, including cadaverine, methyl mercaptan, and hydrogen sulfide. These VSCs account for many of the air-quality issues encountered in LTC facilities and may contribute to respiratory problems in this population. For instance, a resident constantly inhaling hydrogen sulfide may develop decreased lung function and an impaired ability to taste or smell.3 In rat studies, relatively low oral doses of cadaverine were found to contribute to weight loss.4 Several studies have also shown that the bacteria themselves can migrate, and oral bacteria responsible for causing periodontal disease and caries have been found in vascular plaques and amniotic fluid.5-7 Aspirating oral pathogens or parts of the biomass growing on the teeth contributes to respiratory diseases, including pneumonia, which is one of the top causes of death among LTC residents.

Oral inflammation is also tied to brain health. Long-term evidence demonstrates that periodontal disease may increase the risk of cognitive dysfunction associated with Alzheimer’s disease in healthy individuals and in those who are cognitively impaired.8 Cognitive impairment is common among LTC populations, and one can surmise that maintaining oral health in these individuals may provide some protection against cognitive decline.

The negative physiological outcomes of continuously inhaling VSCs or of oral bacteria migrating to other parts of the body may trump the quality-of-life effects of dealing with fetid halitosis, a problem all too often considered to be purely cosmetic. In dependent adult living situations, air quality improvement can be achieved by supporting oral health initiatives that strive to remove oral biofilm as often per week as possible.

Oral Care Education

As the incidence of edentulism (the absence or complete loss of teeth) decreases, an increasing number of people are entering LTC facilities with more teeth intact. Because elderly patients often have compromised salivary function, they can quickly develop dental decay and periodontal disease when the growth of the dental biomass on their teeth goes unchecked. In these individuals, the complications of a chronic wound associated with periodontal disease become a reality. Even if individuals do not have the 20 teeth required to serve as the equivalent of a palm-sized wound, the chemistry that normally occurs around each tooth is ongoing; thus, the consequences of poor oral care remain even for these individuals. Education on the importance of oral hygiene needs to be improved in LTC facilities so that the teeth and overall health of these individuals are preserved for as long as possible.

While medicine has long recognized the physiological damage of an open, untreated, infected wound, oral care is still viewed as a benign cosmetic procedure. In textbooks for nurses and nursing assistants, oral care recommendations are generally discussed in the same chapter as hair washing and nail clipping, and the only consequences of poor oral hygiene outlined are those affecting the resident’s dignity, such as bad breath and dental decay. While some textbooks may also cover oral care in sections that review ventilator-associated pneumonia or nursing home–associated pneumonia, the sequelae of poor oral hygiene are overlooked, with no mention of the multitude of other disease processes that can result from oral hygiene deficiencies.9 In addition, textbooks often use antiquated terms like pyorrhea to describe advanced periodontal disease, which is a World War I–era term that is no longer used in the dental world. It is clear that educating medical professionals on oral care issues is currently an afterthought or a low priority in LTC settings.

Inadequate oral care in dependent care settings is a worldwide problem. A PubMed search reveals studies across the globe addressing inadequate oral care in LTC facilities.10-12 Although everyone agrees that a lack of oral care is problematic, everyone thinks the problem exists elsewhere.13,14 Nursing education about oral care would be more accurate and effective if it was treated similar to wound care, as this would acknowledge the role of oral health in maintaining overall health.

Role of the Dental Hygienist

Certified nursing assistants are normally in charge of the oral care of each resident. Although nurses are not always involved, they traditionally write the textbooks that are used to teach nursing assistants. These textbooks generally state that brushing should be attempted after meals and flossing should be attempted at least once daily.15 While these recommendations sound good, they may not be practical. Dental hygienists should be involved in authoring texts for nursing assistants that cover oral care, as the nuances of oral care are best addressed by individuals who dedicate their lives to dental hygiene and have an understanding of how to work with specialty nurses, LTC facilities, hospice providers, cancer hospitals, and other healthcare professionals and organizations.12,14

Nurses who write, collaborate on, or act as the editor of textbooks that cover oral care should make sure a dental hygienist is on the editorial board of the textbook. Ideally, oral care would receive its own chapter, rather than being grouped with cosmetic issues. A dental hygienist can act as the author of the oral care chapter and contribute to other sections of the book, including those discussing diabetes and cancer care.

It is unlikely that a nursing assistant will be able to provide oral care for each resident more than once daily, which is contrary to the textbook recommendations; however, research has shown that professional oral care provided by a dental hygienist lowers the incidences of respiratory diseases among nursing home residents and mucositis among individuals undergoing treatment for cancer.16-20 While hiring a dental hygienist may require legislative changes, depending on the state, having a dental hygienist on the team can contribute to a superior level of care or provide oversight to nursing assistants in developing oral care plans tailored for each resident.12,14

Take-Home Message

Oral hygiene is not a cosmetic concern. Oral disease, particularly periodontal disease, represents a wound the size of a person’s palm. Periodontal pathogens and bacteria that cause dental caries have been found in amniotic fluid, vascular plaques, and the lungs. As a biofilm grows on the teeth, it acts as a breeding ground for more than 500 pathogens, which release VSCs. These pathogens or the VSCs that they emit can be aspirated or enter the bloodstream, contributing to chronic health issues, including respiratory diseases, cardiovascular problems, and impaired cognition; however, providing professional oral care via regular visits with a dental hygienist can reduce the biofilm. In addition, changing the education of nurses and nursing assistants to focus on the sequelae of oral biofilm may improve the overall health of residents by elevating oral care from a cosmetic issue to a medical concern.

The author reports no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. How flossing teeth can prevent lung disease. www.realage.com/blogs/doctor-oz-roizen/how-flossing-teeth-can-prevent-lung-disease. Accessed May 10, 2011.

2. Hujoel PP, White BA, García RI, Listgarten MA. The dentogingival epithelial surface area revisited. J Periodontal Res. 2001;36(1):48-55.

3. Safety data for hydrogen sulfide. https://msds.chem.ox.ac.uk/HY/hydrogen_sulfide.html. Accessed May 9, 2011.

4. Til HP, Falke HE, Prinsen MK, Willems MI. Acute and subacute toxicity of tyramine, spermidine, spermine, putrescine, and cadaverine in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 1997;35(3-4):337-348.

5. Kimizuka R, Kato T, Ishihara K, Okuda K. Mixed infections with Porphyromonas gingivalis and Treponema denticola cause excessive inflammatory responses in a mouse pneumonia model compared with monoinfections. Microbes Infect. 2003;5(15):1357-1362.

6. Abranches J, Miller JH, Martinez AR, et al. The collagen-binding protein Cnm is required for Streptococcus mutans adherence to and intracellular invasion of human coronary artery endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 2011;79(6):2277-2284.

7. Gauthier S, Tétu A, Himaya E, et al. The origin of Fusobacterium nucleatum involved in intra-amniotic infection and preterm birth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez/21314291. Accessed June 16, 2011.

8. Kamer AR, Craig RG, Dasanayake AP, et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease: possible role of periodontal diseases. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4(4):242-250.

9. Glassman P, Subar P. Creating and maintaining oral health for dependent people in institutional settings. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70(Suppl 1):S40-S48.

10. Chung JP, Mojon P, Budtz-Jørgensen E. Dental care of elderly in nursing homes: perceptions of managers, nurses, and physicians. Spec Care Dentist. 2000;20(1):12-17.

11. Forsell M, Sjögren P, Johansson O. Need of assistance with daily oral hygiene measures among nursing home resident elderly versus the actual assistance received from the staff. Open Dent J. 2009;3:241-244.

12. Monajem S. Integration of oral health into primary health care: the role of dental hygienists and the WHO stewardship. Int J Dent Hyg. 2006;4(1):47-51.

13. Pyle MA, Jasinevicius TR, Sawyer DR, Madsen J. Nursing home executive directors’ perception of oral care in long-term care facilities. Spec Care Dentist. 2005;25(2):111-117.

14. Smith BJ, Ghezzi EM, Manz MC, Markova CP. Perceptions of oral health adequacy and access in Michigan nursing facilities. Gerodontology. 2008;25(2):89-98.

15. Hardy DL, Darby ML, Leinbach RM, Welliver MR. Self-report of oral health services provided by nurses’ aides in nursing homes. J Dent Hyg. 1995;69(2):75-82.

16. Abe S, Ishihara K, Okuda K. Prevalence of potential respiratory pathogens in the mouths of elderly patients and effects of professional oral care. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2001;32(1):45-55.

17. Okuda K, Kimizuka R, Abe S, et al. Involvement of periodontopathic anaerobes in aspiration pneumonia. J Periodontol. 2005;76(11 Suppl):2154-2160.

18. Adachi M, Ishihara K, Abe S, et al. Effect of professional oral health care on the elderly living in nursing homes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94(2):191-195.

19. Adachi M, Ishihara K, Abe S, Okuda K. Professional oral health care by dental hygienists reduced respiratory infections in elderly persons requiring nursing care. Int J Dent Hyg. 2007;5(2):69-74.

20. Kashiwazaki H, Matsushita T, Sugita J, et al. Professional oral health care reduces oral mucositis and febrile neutropenia in patients treated with allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Support Care Cancer. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21328006. Accessed June 2, 2011.