Acute Pancreatitis From Gastrostomy Tube Migration in a Nursing Home Resident

Feeding tubes are commonly placed in nursing home residents. While complications such as acute pancreatitis secondary to gastrostomy tube migration are rare, they can occur. The authors report one such case in a young nursing home resident who initially presented to the hospital with nonbilious vomiting, restlessness, and agitation. In conducting a literature review, the authors identified a few similar cases, highlighting the need to consider this rare complication in any patient who has a feeding tube and presents with distressing gastrointestinal symptoms, especially if a workup reveals elevated serum pancreatic enzyme levels.

Acute obstructive pancreatitis resulting from mechanical obstruction of the duodenal papilla due to migration of a gastrostomy tube (G-tube) is a rare and infrequently reported complication of G-tube placement. A comprehensive literature search using PubMed and Ovid revealed fewer than 10 case reports or series. Migration has been associated with using these tubes without external bumpers, using Foley catheter G-tubes, and not performing radiologic confirmation after G-tube placement to ensure that the tube is in the correct position. In patients who are debilitated, bedbound, and nutritionally dependent, accidental manipulation of the tube by patients or their caretakers may further increase the risk of tube migration. We report the case of a young nursing home resident who developed acute pancreatitis following migration of his G-tube. This case serves to illustrate the importance of early recognition and management of this unusual complication of G-tube placement.

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old male nursing home resident with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, alcohol abuse, and stroke resulting in expressive aphasia, debility, and long-term G-tube placement, was brought to the hospital for evaluation of a 1-day history of abdominal pain, nonbilious vomiting, restlessness, and agitation. Upon hospital admission, an assessment of his vital signs revealed tachycardia with a pulse rate of 117 beats per minute, blood pressure of 154/98 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute, and an oxygen saturation of 99% while on oxygen delivered at 2 L/min via a nasal cannula. On physical examination, the patient intermittently clutched his abdomen because of abdominal pain, was nonverbal, and appeared anicteric, thin, and frail. An abdominal examination revealed a soft, nontender, nondistended abdomen on palpation and normal bowel sounds on auscultation. The G-tube site appeared normal. Cardiovascular, respiratory, and musculoskeletal examinations were unremarkable. Laboratory findings revealed a white blood cell count of 19,600/µL (normal, 4500-11,000/µL), alanine aminotransferase of 11 U/L (normal, 10-40 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase of 17 U/L (normal, 10-30 U/L), alkaline phosphatase of 63 U/L (normal, 30-120 U/L), total bilirubin of 0.3 mg/dL (normal, 0.3-1.2 mg/dL), serum lipase of 1745 U/L (normal, 31-186 U/L), and amylase of 1454 U/L (normal, 27-131 U/L). The patient’s lipid profile was within normal limits.

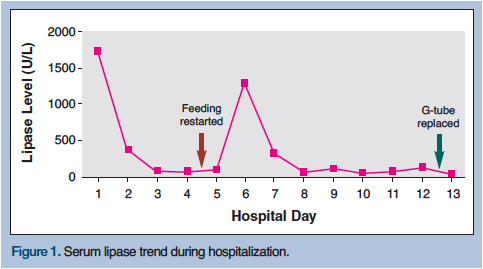

Based on the findings of elevated serum pancreatic enzyme levels and abdominal pain, a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis of unknown etiology was made and his tube feedings were temporarily discontinued. On hospital day 4, the patient’s clinical picture improved, including his symptoms of agitation, and his lipase level was found to be in the normal range at 91 U/L, resulting in his tube feedings being restarted (Figure 1); however, the following day, the patient once again showed signs of agitation and his lipase level rose to 116 U/L, and on the second day following the commencement of tube feeding, they rose to 1300 U/L. At that time, the patient’s tube feedings were again withheld, and an evaluation to determine the cause of his elevated pancreatic enzyme levels was undertaken.

Ultrasonography, as part of the patient’s ongoing work up, did not reveal any gallstones, his lipid levels were within normal limits, and his medical records revealed no recent history of ethyl alcohol use or medication changes; however, an association between the elevation in his serum pancreatic enzyme levels and tube feedings was noticed. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous contrast was performed, which revealed that the G-tube had migrated out of the stomach and traveled through the pyloric sphincter into the duodenum, leading to obstruction of the major duodenal papilla (Figure 2). Following removal of the old tube and placement of a new G-tube, which occurred at the patient’s bedside, the patient’s pain was relieved, his lipase levels quickly normalized, and the feedings were well tolerated. This dramatic response to treatment confirmed the diagnosis of acute obstructive pancreatitis secondary to a migratory G-tube. The patient’s serum lipase level upon hospital discharge was 46 U/L and he was back to his usual state of health.

Discussion

G-tubes are increasingly being used to facilitate nutritional supplementation in persons who have limited or no oral intake.1 In 1993, Hull and colleagues2 reported G-tube placement to have a low complication rate, with few serious or long-term consequences.2 Earlier studies had demonstrated similar findings and estimated procedure-related mortality to be less than 1%.3,4 Acute obstructive pancreatitis caused by the mechanical obstruction of the major duodenal papilla secondary to G-tube migration seems to be a rare and infrequently reported entity, with our literature search on PubMed and Ovid yielding fewer than 10 case reports or series.

Cases in the Literature In 1956, a review of a series of 125 gastrostomies noted two cases of gastrointestinal obstruction from G-tube migration, one of which was fatal.5 In 1978, Gustavsson and Klingen6 reported a case of an obstructed duodenum from a Foley catheter G-tube, which resulted in obstructive jaundice.6 In 1986, Bui and Dang7 reported the first case of acute pancreatitis caused by the inflated balloon of a Foley catheter G-tube migrating into the patient’s duodenum. In this case, the patient presented with severe bilious vomiting, epigastric pain, and elevated serum and urine amylase levels. A barium follow-through showed that the catheter had migrated into the second portion of the duodenum. Once the catheter was removed, the patient’s symptoms and clinical picture resolved. The authors noted that careful fixation of the G-tube to the abdominal wall can prevent this complication. 7 In 1988, the first case of acute pancreatitis resulting from G-tube migration in a pediatric patient was reported by Panicek and colleagues.8 In this case, the G-tube balloon had been inadvertently placed in the descending duodenum, highlighting the importance of obtaining radiologic confirmation that the tube is in the correct position. In 1991, Barthel and Mangum9 reported a case of acute pancreatitis in a patient with pancreatic divisum, whose Foley catheter G-tube had migrated and mechanically obstructed the minor duodenal papilla. Treatment included removal of the Foley catheter and placement of a Witzel tunnel jejunostomy. In 2001, Duerksen10 reported a case of acute pancreatitis in a young woman with cerebral palsy whose 16 French balloon G-tube had migrated into the second portion of the duodenum, despite the presence of an external bumper. It is thought that the tube’s external bumper had loosened, allowing the migration.

In 2005, Miele and Nigam11 reported a case of obstructive jaundice and pancreatitis secondary to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube migration, and in 2007, Imamura and associates12 reported a case of acute pancreatitis and cholangitis resulting from migration of an 18 French balloon PEG tube in an elderly Japanese woman. In this case, 1 month before the patient’s hospitalization for this complication, her physician had replaced her PEG tube and its external disc bumper in her home. As with the case reported by Panicek and colleagues,8 there was no radiologic confirmation that the tube had been positioned correctly. Imamura and associates concluded that a malpositioned PEG tube can be an iatrogenic cause of acute pancreatitis and cholangitis, making it important to secure the PEG tube at the skin level. In their report, the authors also noted that of the 5 cases of pancreatitis resulting from a migratory G-tube that they identified in the literature, 4 involved a Foley catheter G-tube.

G-Tubes Versus PEG Tubes

Throughout the literature, the terms G-tubes and PEG tubes are often used interchangeably, including by Imamura and associates.12 For example, when these authors discuss the article by Bui and Dang,7 they use the term PEG tube despite Bui and Dang’s original report outlining the use of G-tubes, not specifically PEG tubes. While procedural differences may exist how these tubes are placed (ie, endoscopic vs operative), the management thereafter is the same. In addition, each tube is secured with a fixating device such as a bumper and has the propensity to migrate, resulting in the complications outlined in this paper.

In 1990, Stiegmann and associates13 conducted a prospective randomized trial examining operative versus percutaneous placement of G-tubes. The authors found no difference in mortality, morbidity, or tube function between these routes of placement; thus, there is no clear evidence indicating a correlation between the risk of migration and the procedure used to place the tube. It is for this reason that we do not distinguish between tubes that are placed operatively versus endoscopically in this paper. Clinicians should remember that any feeding tube can migrate and cause complications.

Mechanism of G-Tube Migration

The underlying mechanism for G-tube migration is thought to be intestinal peristalsis, which carries the tube through the duodenum once it crosses the pyloric sphincter. The risk for migration is increased if the tube is pushed too far upon its initial placement or if the external bumper securing the tube becomes loose, as this may cause the tube to be gradually pushed further into the abdominal cavity.12 In our patient, we observed that his serum lipase levels would only spike at the commencement of tube feedings and would downtrend once the feedings were stopped, despite the presence of a constant mechanical obstruction from the inflated G-tube balloon. Because the balloon does not inflate or deflate as feeds are passed through it, we propose that the spike in lipase levels were due to the well-known stimulation of pancreatic exocrine and endocrine function from enzymes, such as cholecystokinin, secretin, and gastric inhibitory peptide, when food particles enter the duodenum.14 Secretion of pancreatic enzymes against a blocked papilla would explain the aforementioned elevations that we observed in his serum lipase levels.

Conclusion

Our report adds an additional case of acute pancreatitis resulting from G-tube migration to the literature. When presented with a patient with a G-tube who has acute pancreatitis, a diagnosis of acute obstructive pancreatitis secondary to a migratory G-tube must be considered. Residents of long-term care facilities often receive supplemental nutrition through a G-tube; thus, this population has a greater risk of this rare complication. In such individuals, prompt imaging with either plain film radiography of the abdomen or a contrast-enhanced CT scan can help identify this condition. Once diagnosed, the definitive treatment is removal of the obstruction and placement of a new G-tube, which should lead to normalization of serum pancreatic enzyme levels and resolution of symptoms. Early recognition of this unusual etiology of acute pancreatitis and prompt management can reduce the length of hospitalization and improve patient outcomes.

1. Faries MB, Rombeau JL. Use of gastrostomy and combined gastrojejunostomy tubes for enteral feeding. World J Surg. 1999;23(6):603-607.

2. Hull MA, Rawlings J, Murray FE, et al. Audit of outcome of long-term enteral nutrition by percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Lancet. 1993;341(8849):869-872.

3. Park RH, Allison MC, Lang J, et al. Randomised comparison of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and nasogastric tube feeding in patients with persisting neurological dysphagia. BMJ. 1992;304(6839):1406-1409.

4. Wicks C, Gimson A, Vlavianos P, et al. Assessment of the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding tube as part of an integrated approach to enteral feeding. Gut. 1992;33(5):613-616.

5. Connar RG, Sealy WC. Gastrostomy and its complications. Ann Surg. 1956;143(2):245-250.

6. Gustavsson S, Klingen G. Obstructive jaundice-complication of Foley catheter gastrostomy. Case report. Acta Chir Scand. 1978;144(5):325-327.

7. Bui HD, Dang CV. Acute pancreatitis: a complication of Foley catheter gastrostomy. J Natl Med Assoc. 1986;78(8):779-781.

8. Panicek DM, Ewing DK, Gottlieb RH, Chew FS. Gastrostomy tube pancreatitis. Pediatr Radiol. 1988;18(5):416-417.

9. Barthel JS, Mangum D. Recurrent acute pancreatitis in pancreas divisum secondary to minor papilla obstruction from a gastrostomy feeding tube. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37(6):638-640.

10. Duerksen DR. Acute pancreatitis caused by a prolapsing gastrostomy tube. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54(6):792-793.

11. Miele VJ, Nigam A. Obstructive jaundice and pancreatitis secondary to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube migration. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20(11):1802-1803.

12. Imamura H, Konagaya T, Hashimoto T, Kasugai K. Acute pancreatitis and cholangitis: a complication caused by a migrated gastrostomy tube. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(39):5285-5287.

13. Stiegmann GV, Goff JS, Silas D, et al. Endoscopic versus operative gastrostomy: final results of a prospective randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36(1):1-5.

14. Ganong WF. Review of Medical Physiology. 21st ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2003.