Working Together to Assure the “Right” Medication for the “Right” Patient

Think of the world of accessing medications as a big bull’s eye. In Medicare’s perception, that is exactly the way that the market for pharmaceuticals should be viewed. Medicare believes it must play a very active role, as it believes that many key players will aim poorly, completely missing their desired target. And in the worst-case scenarios, prescribers’ aim will be so poor that they may actually wind up hitting patients who have adverse events because of access to an inappropriately prescribed medication. Rofecoxib is an example of “poor shooting” because of inadequate oversight, or so the typical congressional and regulatory argument would make it seem.

As a result of Medicare’s rise to the position of major payor for medications, Medicare believes that it needs to be very involved in medication management. Medicare is focusing on what the target looks like, and expects prescribers’ to hit a defined mark with perfect accuracy. The ideal is a world of “individualized medicine” where the exactly right medications are provided for each patient’s needs.

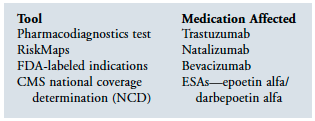

Medicare is utilizing many tools to assure that the right patient receives the right medication. These tools include defining access through specific diagnostic testing, RiskMaps, and narrowing of indications. It is also working to control external influence on patients and prescribers, as well as utilizing technology. But its tools go beyond these and include Medicare Part D guidance and regulations. In addition, the movement toward a pay-for-performance system is driven by the goal of encouraging providers to more appropriately manage medications.

How Medicare is doing this is of extreme interest to all stakeholders and will guide how medications will be managed. But in addition to acknowledging Medicare’s growing dominance in this process, clinicians and their patients can play a major role to influence the course that medication access takes.

Defined Access

To start, the federal government is defining who can have access to specific medications. This is done primarily in three ways:

(1) requiring specific diagnostic testing,

(2) utilizing FDA RiskMaps, and

(3) narrowing the indications.

Each of these tools is utilized to assure that specified medications are provided to the “right” patient. Obviously, we need to assure that the definition of “right” is clinically appropriate, being based on the best available evidence. In the case of the erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), many have argued that the indications being applied are far too narrow, eliminating many patients who would benefit from having access to these medications.

Recently, the FDA considered strongly refusing to expand access of bevacizumab to women suffering from breast cancer. This consideration arose despite the fact that clinical trials demonstrated the longest reported “progression-free survival” for patients with advanced breast cancer through the use of bevacizumab.1 An editorial in The Wall Street Journal noted that advanced therapies often prove more effective within targeted populations in some patients more than others. This is the problem when making decisions for large populations instead of for individual patients. While some individuals may in fact benefit from a given medication, others may be harmed by the same medication. Basing decisions as the FDA currently does on large general populations is contrary to individualized treatment plans. In this case, the narrow focus of the bull’s eye is restricting access for patients who would benefit from these medications. In the case of bevacizumab, the target was expanded because of the pressure applied by clinicians and patients.

A prime example of a pharmacodiagnostics test is the assessment of HER2 receptor expression in breast cancer tumors. The humanized therapeutic monoclonal antibody trastuzumab was designed to target HER2, which, when overexpressed, is associated with an aggressive form of breast cancer and poor clinical outcome. When trastuzumab was approved in the United States in 1998 for the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (MBC), a specific diagnostic IHC assay was approved at the same time for the selection of eligible patients with MBC, marking the first simultaneous regulatory approval of a targeted drug and its corresponding diagnostic test.

Of course, assuring that a specific medication is right for a patient goes beyond criteria; it can sometimes be defined by a specific diagnostic test. Such is the case with many oncology classifications. Genetic Testing and Diagnostic Tools in the Pharmacy Benefit2 examines the evolving presence and impact of genetic testing on health plans and the pharmacy benefit industry.

These tests can go a great distance in identifying the patients likely to have the greatest gain from utilizing a specific medication. These diagnostic-specific tests have been utilized in the area of oncology treatments for some time to best assure using specific tumor markers that the right patient is receiving the right medication.

Influencing Key Stakeholders

In the area of controlling the influence of key stakeholders, the FDA is leading the charge to assure that both consumers and prescribers are not adversely influenced with regard to pharmaceutical companies. This influence is controlled through proposed restrictions on direct-to-consumer advertising, especially in the area of newly launched products. Professional detailing restrictions continue to be applied, as well as the use of academic detailing to promote greater use of generic medications.

Clinical practice guidelines, of course, are another major way to attempt to affect prescriber behavior, although the time lag in which behavioral change occurs may be extensive. In addition to the delay in affecting prescriber behavior, clinical guidelines may do more to confuse than to provide direction. Take, for example, the recently released dementia guidelines,3 which carry the following statements: “Currently, we have no way to predict which patients might have a clinically important response. Therefore, the evidence does not support prescribing these medications for every patient with dementia.” Basically what this says is that since we cannot tell who will respond best, we shouldn’t treat broadly.

Think for a moment if that same logic, or lack thereof, were applied to cancer treatments (ie, since we can’t tell who will respond, we should hold back therapy from some). It’s uncertain what the basis should be for holding back therapy. Expressed another way, clinicians should not shoot at the target because we can’t be sure where the bull’s eye is. Of course, if we missed our shots, this could cause significant harm; however, since these misses in the case of dementia treatments cause few adverse effects, our ability to hit the mark (which can result in clinical improvement) begs the questions as to why we wouldn’t take as many shots as possible.

In addition, the dementia guidelines carried a recommendation that there is an urgent need for further research on the clinical effectiveness of pharmacologic management of dementia. Instead, although it would be valuable to of course find innovative new treatments for dementia, it may be more valuable to better identify those patients who would respond best. By clearly identifying the target and providing the means to hit it, a real contribution to the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease can be provided.

Technology

Technology has the ability to ensure that at the point of prescribing, clinical evidence is utilized to assure that the most appropriate prescription is written. This technology includes both electronic prescribing as well as the use of electronic health records. By integrating into these technologies evidence-based knowledge prescribers, can be directed to the most appropriate medications for their patients. Unfortunately, we are still a long way away before ePrescribing and electronic health records loaded with clinically important prescribing resources are readily available and affordable for routine clinical use.

Medicare Part D

Of course, federal legislators, as well as the CMS, have utilized guidance and regulations around Medicare Part D to promote the use of specific medications, while at the same time restricting access to others. These regulations and guidance include the use of the six protected classes.

At the other end of the spectrum is the list of medications specifically excluded from being covered under Medicare Part D. Also, in between those medications that are specifically included or excluded is the effect of the “doughnut hole,” the part of the benefit that forces Medicare beneficiaries to be responsible for 100% of the cost of medications, which was designed in part to give Medicare beneficiaries “skin in the game.” A belief that Medicare beneficiaries need to have a real understanding of the cost of their prescription drugs is a costly lesson to teach. While this may get Medicare beneficiaries to understand the cost of their medication, it also forces many to become non-adherent to those medications needed to manage their chronic comorbid conditions.

Another relatively new change is CMS’ elimination of the requirement on the part of plans to include at least one medication within each of the United States Pharmacopeia’s Formulary Key Drug Types (FKDT). The classes most affected by this change include the antibacterial, antiparkinsonian, antidiabetic, and cardiovascular agents. This change was designed to allow Medicare Part D plans greater latitude in potentially restricting access to medications through greater utilization control measures.

The principal tool that Medicare has to assure that the target is hit with regard to the right medications for that particular patient is the medication therapy management (MTM) program, although MTM still is a far cry from what Medicare and others believe it should be at this point. To shore up the MTM program, Medicare is developing measures to hold plans accountable to see that their programs are on target.

Currently, MTM is being used mainly not to assure that the “right” medication is used for the right patient on a purely clinical basis, but on a cost basis as well. Through the use of Least Costly Alternative (LCA) and Therapeutic Interchanges (TI), Medicare is able to promote the use of the less expensive medication, even if evidence supports a greater clinical benefit of the more expensive alternative in that class.

Pay for Performance

Dollars are not only being utilized as a driver to assure the use of less expensive medications but to provide incentives for more efficient and effective therapies. These dollars are being utilized through Medicare’s pay-for-performance programs. These programs have taken many different approaches including those directly involving physicians such as the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI), to those involving hospitals through the principle of present on admission (POA). In the first year of the PQRI program, only about 15% of physicians participated in this program.

Assuring “Right” is “Right”

Oftentimes a tremendous opportunity is lost because patient and physician input is not adequately obtained regarding the policy and regulatory decisions developed about medication management. Patients and clinicians can affect these areas discussed in very positive ways.

One way that patients can work together to assure access to necessary treatments is through advocacy groups. This was the case with regard to Medicare Part D guidance that forced plans to cover substantially all of the treatments in several classes of medications needed by mental health patients, such as atypical antipsychotics and antidepressants. Currently, Medicare Part D plans are pressing CMS for relief of this requirement. It will only be through the force of patient advocacy groups that access to substantially all of the medications in these classes remains available.

In the end, clinicians and their patients will either be restricted regarding medication management by others or, preferably, will be guided appropriately as all of the key stakeholders—policymakers, regulators, patients, and their clinicians—work together. We need to collaborate and focus together to assure that the medications and other therapies we prescribe hit the target as accurately as possible.

Please send any questions or experiences about Medicare you would like to share with readers to: bspivack@lifecare.com