Treating Restless Legs Syndrome—Where’s the Evidence?

This is one in a series of articles presenting information resources relevant to long-term care issues. Emphasis is placed on sources that might not show up in a typical journal search.

Evidence-based practice has become the goal, if not the standard, for modern medicine. Geriatrics is not unique in its need to continually strive for more and better evidence for what we do. But where do we look for evidence-based medicine sources? This article reviews some sources available through the Internet. To make it more instructive (and more fun), a not-uncommon geriatric and long-term care problem is used as an example.

THE CASE

A 70-year-old man complains of difficulty sleeping. His wife says she had to move out of the bedroom because he moved his legs in bed and disturbed her. He admitted he often had the uncontrollable urge to rub or move his legs because of “creepy, crawling” sensations. He does not have any leg pain, nightmares, or dyspnea. Tests for iron deficiency and renal disease were normal.

DIAGNOSIS AND PREVALENCE

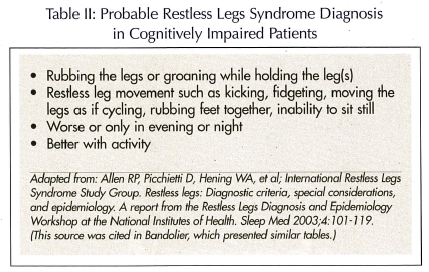

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a condition that causes an uncomfortable need to move the legs (Table I). Patients may describe itching, burning, pulling, throbbing, or “creepy, crawly” sensations. The diagnosis is based on history. Among cognitively impaired patients, the history may not be offered, so diagnosis depends on observation of characteristic behavior (Table II). A sleep study may identify periodic leg movements, often associated with RLS. Five to twenty percent of the population may have RLS, and the prevalence increases with age. In a telephone survey in Kentucky, the prevalence rose from 3% at ages 18-29, to 10% at ages 30-39, and almost 20% at age 80 and older.1 In addition to age, RLS was associated with body mass index, low income, smoking, lack of exercise, low alcohol consumption, and diabetes. (It is also more common in pregnancy, affecting over one-fourth of women in one study.2)

TREATMENT

“Treatment (of RLS) can be difficult and often requires trying different drugs….”3 This textbook statement clearly implies vagueness in the treatment evidence base. If you wish to check out the latest evidence-based treatment of RLS, where can you look?

The Cochrane Library

Often first-cited as a source of evidence-based medicine (EBM), the Cochrane Library4 focuses on treatment and now has over 2000 reviews. It’s named in honor of Archie Cochrane,5 an English physician-epidemiologist, who once noted: “I had considerable freedom of clinical choice of therapy; my trouble was…that there was no real evidence that anything we had to offer had any effect….” His subsequent writings encouraged the EBM movement. Reviews are free for clinicians and the public in England; for others it’s a subscription service, but single full-text articles can be purchased. However, many of the abstracts are free. We searched the Cochrane Library but did not find a recent review to help with treating our case.

Bandolier

A bandolier, or bandoleer, is a belt with slots for bullets, often worn over one shoulder and across the chest. The word is derived from Spanish for a band of men. Bandolier6 finds reports of effectiveness and puts forth summaries in bullet style. It originates from Oxford University, and access is free. It turns out that RLS is featured in Bandolier, and a number of hits (pertinent sources) were found, although only three recent clinical trials were cited. These trials evaluated pergolide,7 gabapentin,8 and ropinirole.9 All of these drugs were found to be superior to placebo.

National Guideline Clearinghouse

Maintained by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, all the guidelines in the National Guideline Clearinghouse™10 are supposed to be “objective,” but the evidence base of submitted guidelines is not subjected to high-level standards. Furthermore, since self-interest groups can submit guidelines, the quality of the evidence base of individual guidelines can vary. We found no evidence-based treatment recommendations for RLS.

PubMed

If you haven’t found it on your own, let us introduce you to “Clinical Queries” in PubMed.11 This is not your old PubMed. It’s a new section, introduced in January 2005, and it is, for EBM aficionados, hot. It provides specialized PubMed searches, with canned (preprogrammed) search strategies, to produce abstracts targeted to specific subjects. You can search the National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE database for Clinical Studies using either a narrow or broad scheme. Or you can search for Systematic Reviews to find “systematic reviews, meta-analyses, reviews of clinical trials, evidence-based medicine, consensus development conferences, and guidelines.” Go to the PubMed homepage, scan down the frame on the left, and click on “Clinical Queries.” You will be presented with the two options Clinical Studies and Systematic Reviews. We searched for RLS and chose the “narrow” and “therapy” Clinical Studies filters. Our search produced 54 pertinent citations, arranged nicely in reverse chronology. It was easy to pick off a half-dozen clinical trials reported within the past 12 months. There were direct links to the abstracts. These trials reported that ropinirole,12 rotigotine,13 valproic acid,14 and pergolide7 were effective, among others.

SUMSearch

SUMSearch15 is an amazing engine that searches three databases at once, allowing you access to MEDLINE, DARE (see below), and the National Guideline Clearinghouse. It uses contingency searching to fashion the results into most useable packages. SUMSearch was developed because its creators had “a disappointing experience in teaching medical students how to quickly locate medical evidence.” Apparently, the faculty at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, San Antonio, explained how to use filters to optimize searching. However, students did not always use these information retrieval techniques. So the faculty built the filter techniques into SUMSearch. A search using “RLS/intervention” produced a number of citations, but apparently the contingency-searching algorithm decided that the best PubMed search strategy was “broad,” and many of the articles were not relevant.

DARE

DARE stands for Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects.16 All systematic reviews included in this database have passed criteria for methodological quality. DARE is one of the Cochrane databases, but so far, it is free. We didn’t find a current helpful RLS source, but DARE is an important source of current reviews, and should be on any list of EBM sources.

Clinical Evidence

Published by the BMJ Publishing Group, Clinical Evidence17 is also available as a pocketbook, a full-text CD, and a PDA version, as well as on the Internet. It is a subscription service and covers about 200 conditions so far, and over 2000 treatments. RLS is not yet one of the conditions covered.

SUMMARY

The purpose of this article is not to suggest specific treatment for RLS. Rather, it is to present a number of evidence-based medicine sources available on the Internet. RLS was used as a model. The drugs mentioned have potential side effects and are expensive. Clinicians may wish to follow a more conservative approach: “Other than reassurance, treatment is often not needed, although walking, stretching, or rubbing the legs may help.”18 But if clinicians wish to find recent evidence-based studies, the sources presented here may be useful. Because the need for evidence-based treatment sources is a periodic challenge, readers may wish to become familiar with one or two sources and bookmark them on their computers.