Pharmacologic Options for Managing Psychosis in Parkinson’s Disease

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD), a progressive movement disorder affecting middle-aged and elderly individuals, is often complicated by psychiatric and cognitive dysfunction. The presence of such impairments not only adds to the disease burden for patients, but also produces significant consequences in terms of quality of life, increased mortality, health care costs, and caregiver stress. Increasing severity of psychiatric symptoms in a substantial portion of patients eventually requires placement in a nursing home.1 Placement in a nursing facility for these patients carries a two-year mortality rate of 25-100%.2 Clearly, recognizing and reducing the presence of comorbid neuropsychiatric symptoms yields benefits in many domains for patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Psychosis occurs commonly in patients with PD being treated with dopaminergic therapy. Prevalence rates have been observed to be as high as 40%.3 Risk factors for psychosis include the presence of dementia, use of dopaminergic agents, and a later age of onset of PD. Visual hallucinations comprise the most common psychotic disturbance.4 Psychosis often evolves during the course of illness. Early on, patients may have insight or be aware that they are experiencing hallucinations. However, this awareness may diminish, especially as cognitive impairment progresses. Psychosis can also manifest as delusions that generally have paranoid content. Paranoid delusions may lead to behavior that puts the patient in danger to themselves or their caregivers.

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a variant of Parkinson’s disease that is significantly associated with psychosis. Visual hallucinations, fluctuating level of consciousness, and parkinsonism are typical symptoms. Many of the principles that apply to the treatment of psychosis in PD also apply to DLB.

Currently, the approach to managing the appearance of psychotic symptoms involves either adjusting Parkinson’s medications or adding other agents. One strategy is to reduce the number or dose of dopaminergic agents. This approach may be necessary in cases where psychosis appears in the context of delirium or acute confusion. However, reducing Parkinson’s medication typically results in increased motor disability.

Alternatively, there are two classes of agents that have been shown to be of benefit for the management of psychosis in PD: the atypical antipsychotics and the cholinesterase inhibitors. These medications were originally developed for the treatment of schizophrenia and dementia, respectively. This article will review the evidence supporting their use in the treatment of psychosis in PD.

ANTIPSYCHOTIC MEDICATIONS

The atypical antipsychotics are Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the treatment of schizophrenia. These agents act as antagonists at dopamine and serotonin receptors. Studies assessing the efficacy for treatment of psychosis in the context of PD have investigated clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine. Haloperidol and other so-called “typical” antipsychotics have offered little benefit for the treatment of psychosis in patients with PD because they exacerbate motor symptoms. Thus, when such agents were the only available antipsychotics, the presence of psychosis generally required the withdrawal of levodopa, resulting in resurgence of motor disability.

The atypical antipsychotics decrease the liability of inducing extrapyramidal symptoms, such as parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia. They also offer improved efficacy for patients with refractory psychotic disorders and negative symptoms. They may improve cognition in some patients with psychosis. The classical dopamine hypothesis of psychosis proposes that it is an overactivity at dopamine receptors that produces psychosis. The typical antipsychotics are believed to exert their effect by blocking the D2 subtype of dopamine receptors in the mesolimbic/mesocortical pathways in the brain. Atypical agents appear to act differently because of a different pattern of dopamine receptor–binding, with reduced activity on receptors that influence motor function in the basal ganglia. As a result, they are efficacious in psychosis with a reduced liability for parkinsonism. Serotonergic blockade is also believed to be important for producing an antipsychotic effect, and in contributing to reducing parkinsonism secondary to dopaminergic blockade. Among the atypicals, risperidone is the most potent dopamine blocker and, thus, has been shown to frequently worsen motor function in PD. Other atypicals are discussed below.

Clozapine

Among the atypicals, clozapine has the longest track record as a treatment for PD psychosis, and has been shown to be effective in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. The most significant side effects are agranulocytosis and somnolence. To reduce the likelihood of clinically significant agranulocytosis, all patients on clozapine require routine hematologic monitoring. Two randomized, placebo-controlled trials have shown clozapine to produce improvements in measures of psychotic symptoms. In the trial conducted by the Parkinson Study Group involving 60 patients with PD, a positive response was found,5 as determined by scales that measure the presence of psychosis, such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Clozapine doses necessary to produce a response were as low as 6.25 mg, and often less than 25 mg, much lower than the doses used in patients with schizophrenia. Clozapine was not associated with any increase of movement disability, as measured on the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. In a large retrospective chart review of clozapine-treated patients with PD in four Parkinson’s disease centers with 187 subjects, clozapine was also shown to be of benefit.6 Hallucinations improved in 89% of patients, and delusions improved in 40% at an average dose of 38.2 mg per day.

In a recent study, long-term use of clozapine was demonstrated to be safe and effective for the management of psychosis in patients with PD.7 Out of 32 patients followed for five years, 19 remained in treatment. Nine patients dropped out secondary to improvement of symptoms, and three patients discontinued treatment as a result of somnolence. No neutropenia appeared during the course of treatment.

Despite apparent efficacy, many clinicians will avoid this medication because of the need for frequent blood monitoring and anticholinergic side effects. Most clinicians will want other therapeutic options.

Olanzapine

Several studies have shown that olanzapine reduces both hallucinations and delusions in PD.8,9 However, olanzapine also appears to worsen motor symptoms in some patients with PD.9 One study showed increased “off” time in a double-blind trial.10 In a comparison study with clozapine, patients on olanzapine exhibited worsening of motor symptoms, prompting early discontinuation of the study.11 Clozapine also produced significantly better improvement in psychosis and activities of daily living without exacerbating symptoms of parkinsonism. Thus, at the current time, olanzapine does not appear to be advantageous over clozapine.

Quetiapine

Quetiapine has also been studied as a treatment for psychosis in PD. Fernandez and others12 found that 20 out of 24 previously untreated patients demonstrated improvement of psychosis with quetiapine. Juncos and colleagues13 demonstrated a significant decrease in psychosis with quetiapine in a 24-week trial of 29 patients whose previous treatment with clozapine, risperidone, or olanzapine had failed. Dosing ranged from 12.5 to 400 mg per day with psychosis improving without worsening of motor function. In a long-term study, quetiapine improved psychosis in 82% of patients.14 Treatment duration was 15 months on a mean dose of 60 mg per day. However, 32% of patients exhibited worsening of motor symptoms. Dementia appears to decrease the chance of response to quetiapine, and to increase the likelihood of negatively impacting motor symptoms.

Quetiapine has been compared to clozapine in several studies. Dewey and O’Suilleabhain15 performed a chart review of patients with PD who were currently under treatment for psychosis. Quetiapine produced a 66% response rate. Failure to respond to quetiapine resulted in a switch to clozapine, with 89% of this group showing response. They proposed using quetiapine as a first-line agent, reserving clozapine for non-responders. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing quetiapine and clozapine, Morgante et al16 assessed medication effects on psychosis and movement dysfunction. The two treatment arms both showed a statistically significant improvement in psychosis with no difference between the two groups. However, movement dysfunction improved in the clozapine arm and not in the quetiapine arm.

Based on these data, quetiapine is an effective agent for psychosis in patients with PD, and is a viable alternative to clozapine.

CHOLINESTERASE INHIBITORS

While antipsychotics reduce and attenuate psychosis in many patients with PD, a subset of patients experience adverse effects resulting from dopamine blockade. Symptoms include not only the previously mentioned extrapyramidal side effects and worsening of motor symptoms, but also precipitation of confusion and autonomic instability. Patients with parkinsonian features, including those who meet criteria for DLB, demonstrate increased susceptibility to these adverse reactions. As high as 50% of patients with DLB demonstrate this increased sensitivity, and mortality may increase two to three times with antipsychotic exposure.17 For this reason, antipsychotics, including the newer atypicals, must be used with caution.

Accumulating evidence supports the use of cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of PD psychosis in patients with dementia. The cholinesterase inhibitors are approved for the treatment of Alzheimer’s dementia (AD). Rivastigmine and donepezil have been studied the most for PD psychosis. Within the past year, memantine has received FDA approval for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD, and awaits completion of studies looking into its utility for treating psychosis in PD.

As in patients with AD, patients with DLB and PD have abnormal cholinergic function. In fact, decreased levels of choline acetyltransferase may be associated with psychosis in DLB and PD. Choline acetyltransferase levels are lower in the neocortex in patients with DLB and PD compared to patients with AD, based on autopsy studies.18-20 Thus, there is a reason to consider procholinergic therapy in the management of PD and DLB. However, caution must be exercised as cholinergic activation can theoretically exacerbate parkinsonism.

Donepezil

The cholinesterase inhibitors have been evaluated in dementia for effect on neuropsychiatric symptoms as well as on cognitive dysfunction. Donepezil, an approved treatment for mild-to-moderate Alz- heimer’s disease, has shown promise in reducing behavioral problems and psychotic symptoms in PD. Importantly, for PD, donepezil does not appear to produce parkinsonism or to exacerbate motor dysfunction in most patients.21 In open-label studies, hallucinations and delusions improved by 53-100% based on scales measuring psychotic symptoms.22 Dosing ranged from 5-10 mg per day. In one study comparing patients with AD and DLB, the DLB group responded better to donepezil on measurements of both cognitive status and behavioral problems.23 Rivastigmine Rivastigmine has been studied in a randomized, controlled trial for the management of DLB psychosis.24 This double-blind trial observed 127 patients. Patients receiving rivastigmine at doses up to 12 mg per day for 20 weeks demonstrated a significantly better response rate than patients receiving placebo, based on a threshold of a > 30% decrease in psychotic symptoms. Significant benefit for cognitive ability was also found with faster performance on neuropsychological testing. Furthermore, it has been shown that the gains made with treatment persist over time. Monitoring of patients with DLB who were treated for 96 weeks with rivastigmine demonstrated that neuropsychiatric improvement, found at 24 weeks, persisted.25 Thus, rivastigmine appears to be an efficacious treatment with potential long-term benefits.

CONCLUSION

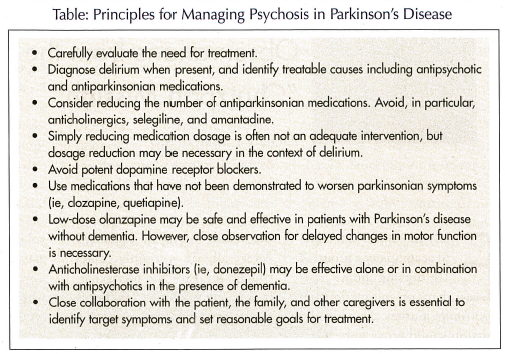

With the availability of antipsychotics and cholinesterase inhibitors, it is possible to reduce the impact of psychosis in PD without reducing the benefit of dopaminergic therapy for movement dysfunction. The Table outlines the main considerations in the management of PD psychosis. With appropriate selection of therapy, patients and their families benefit from the reduction or elimination of symptoms that impact markedly on the quality of life.