Health Literacy as a Tool to Improve the Public Understanding of Alzheimer’s Disease

Introduction

The ultimate goal of health literacy is to improve care by enhancing the patient’s quality of life, maximizing clinical outcomes, and reducing inequities in health.1,2 Successful restructuring of the healthcare system to make it more effective, efficient, and equitable demands that health literacy be integrated as a key source of theoretical and empirical data regarding patients’ needs and wishes. This applies across the life course, but it is especially true for the increasing numbers of older adults who must deal with the medical care system the most, yet often comprehend medical information the least.

Nearly nine out of ten people in the United States do not have the level of proficiency in health literacy skills necessary to successfully navigate the healthcare system.3,4 According to the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL), populations overrepresented at the lowest levels of health literacy (below basic level) in the United States include people over age 65, those who did not graduate from high school, persons who did not speak English before starting school, people who have poor health status, those who are of racial and ethnic minority groups, and individuals without medical insurance.4

An increasing number of efforts are ongoing across the United States and internationally to address health literacy. Significant national initiatives include Healthy People 2010,5 the Joint Commission’s report “Improving Health Literacy to Protect Patient Safety,”6 and the U.S. Department of Heath and Human Services Office of the Surgeon General’s “Workshop on Improving Health Literacy.”7 Other organizations attempting to address health literacy include the American Medical Association8 and the Partnership for Clear Health Communication.9 Many organizations are launching successful health literacy–based interventions such as the Canyon Ranch Institute’s Life Enhancement Program, an integrated approach to prevention and wellness.10 Additionally, there are a growing number of curricula addressing health literacy being developed by a wide range of organizations and individuals.11 Equally significant efforts are ongoing in a number of countries around the world, particularly Canada,12 Australia,13 and Switzerland.14

The purposes of this article are to familiarize readers with the concept of health literacy; demonstrate how health literacy can serve as a tool to improve the public’s understanding of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the seventh leading cause of death; and suggest generally applicable strategies for clinicians.

Concept of Health Literacy

Health literacy is a relatively new term most commonly defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”15 Unfortunately, health literacy has at times been construed as having different meanings in various contexts. The earliest definitions focused only on the inabilities of individuals to read and understand information in the healthcare system. However, an international consensus is beginning to emerge to define health literacy as a wide range of skills and abilities, reflecting the extent to which people are able to find, understand, evaluate, communicate, and use health information and concepts to make informed choices, reduce health risks, reduce inequities in healthcare, and increase quality of life in a variety of settings across the life course.16-18 This leads to a robust conceptual framework of health literacy that is characterized by four central domains: (1) fundamental literacy; (2) science literacy; (3) civic literacy; and (4) cultural literacy.2

Fundamental literacy refers to the skills and strategies involved in reading, speaking, writing, and interpreting numbers (numeracy). Science literacy refers to levels of competence with science and technology, including some awareness of the process of science. Civic literacy refers to abilities that enable citizens to become aware of public issues, to become involved in the decision-making process, and to successfully navigate power relationships. Cultural literacy refers to the ability to recognize and use collective beliefs, customs, world-view, and social identity in order to interpret and act on health information. Together, these skills form a framework of health literacy that clinicians can use to help patients and their caregivers to successfully negotiate our increasingly complex healthcare system.

Age-Related Changes That Impact Health Literacy

Age-related changes may adversely impact health literacy in several ways. When warranted, clinicians should screen for these factors to minimize potential misunderstandings. However, great care must be taken when screening. Shame is a negatively compounding factor that can delay successfully identifying or addressing health literacy issues. A more effective strategy than screening is to ethically and nonjudgmentally lower all health literacy barriers for patients and their caregivers.

Sensory impairments such as decreased vision and hearing loss can be easily recognized if the older adult is using corrective lenses or hearing aids, or can be quickly screened using a hand-held eye chart and voice recognition.19 Cognitive impairment can be screened preliminarily using the Mini-Cog test (clock drawing plus 3-item recall).20 Functional limitations in the basic activities of daily living (ADL) such as bathing, dressing, toileting, mobility, and feeding can be evaluated by history and observation.21 Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) such as shopping, cooking, cleaning, medication and financial management, use of the telephone, and transportation are primarily evaluated through personal and collateral history.22 In the typical long-term care (LTC) setting populated by frail elderly individuals, it is almost certain that multiple impairments will adversely affect the older adult’s health literacy skills.

Prevalence and Impact of Impaired Health Literacy

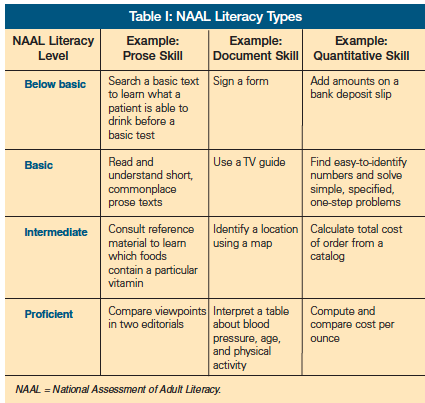

It is likely that older adults will not understand at least part of the healthcare information presented to them. The NAAL assessed the literacy skills, including health literacy, of more than 19,000 individuals from all geographic areas and socioeconomic groups in the country.4 The NAAL ranked health literacy skills into four categories: below basic, basic, intermediate, and proficient (Table I).

NAAL results showed that more than half of people over age 65 are at the below-basic level and, more strikingly, that roughly 98% are below the proficient level of health literacy, which is how most health information is communicated.23,24 Older adult patients with lower health literacy levels use screening/preventive services less, present for care with later stages of disease, are more likely to be hospitalized, have poorer understanding of treatment and their own health, adhere less to medical regimens, have increased healthcare costs, and die earlier.2,25

While the patient’s literacy level is most often the focus of attention, it is important to keep in mind that the health professional’s health literacy skills are also essential for adequate communication.2 This is especially true when patients and caregivers are dealing with AD and other dementias. It is almost certain that at some point during the irreversible progression of dementia, someone will have to provide surrogate health literacy skills for the patient. Engaging the patient and caregiver as early and as often as possible in the important decisions they will face in the future will help provide anticipatory guidance when those skills have been lost.

Tools to Assess Health Literacy

Various instruments are available for assessing health literacy. Most have methodological issues, but a full discussion of those lies outside the scope of this article. At the most, current health literacy measures are very cautiously only recommended for research purposes. These measures include single-item screening questions (eg, “How often do you have someone help you read hospital materials?”),26 the REALM (Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine),27 TOFHLA (Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults),28 NVS (Newest Vital Sign),29 SIRACT (Stieglitz Informal Reading Assessment of Cancer Text),30 MART (Medical Achievement Reading Test),31 LAD (Literacy Assessment for Diabetes),32 and SAHLSA (Short Assessment of Health Literacy for Spanish-speaking Adults).33

However, given the wide prevalence of low health literacy in the elderly population, it is more practical, efficient, and ethical to assume that the majority of patients will need supportive interventions to promote understanding, rather than spending clinical time on health literacy assessment. This is particularly true in the LTC setting.

Example: Alzheimer’s Disease and Health Literacy Barriers

Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias are very common issues in LTC settings, and a simple target for demonstrating how health-literate education materials for patients and healthcare professionals can be of great value. Although only perhaps 20% of older adults and individuals with lower health literacy levels use the Internet for information, many clinicians, public health personnel, families, and caregivers do. The Alzheimer’s Association (AA) website, a primary “go-to” source of information about AD, is useful but unfortunately illustrates many health literacy barriers that individuals can encounter when using the Internet.34

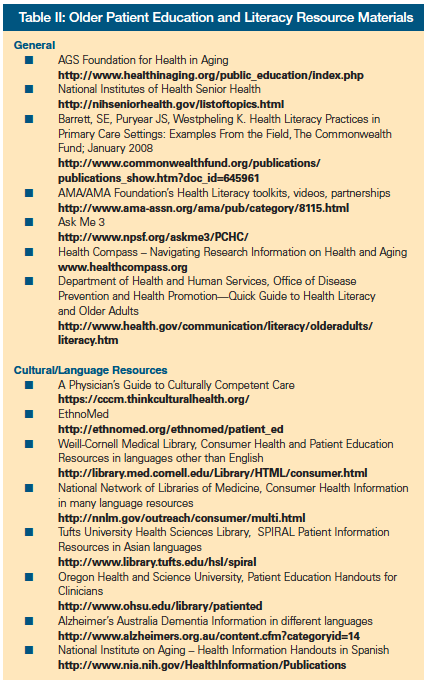

A host of guides and evaluation strategies exist to help users evaluate the health literacy barriers present in many websites (Table II). Based on the four-part definition of health literacy described above, the following list reflects the minimum features necessary for a useful website. This framework is fully extrapolated in other publications.2,16,18

1. Fundamental literacy: A user-friendly website design and all text is written at roughly the 6th-grade level. Fundamental terms in this area of healthcare, such as dementia, are fully and well explained.

2. Scientific literacy: All medical/scientific jargon is explained, including the basis for any scientific uncertainty and an explanation of how and why scientific understanding of health issues may change over time.

3. Civic literacy: Why and how to obtain care is explained. Patients and family are given resources to find or acquire the basic skills they need to navigate the healthcare system. They are empowered to take better care of their own, their families, and their community’s health.

4. Cultural literacy: Differences in how dementia is perceived and treated in multiple cultures is explained. Culturally appropriate and relevant information is provided.

Fundamental Literacy

Regarding fundamental literacy, the AA website, for example, defines key features of AD as being a “progressive and fatal brain disease,” “the most common form of dementia,” and having “no current cure.” When isolated from the surrounding text, these key phrases are at the nearly acceptable readability level of a grade 8.48 educational level, according to the Simplified Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG).35 The SMOG estimates the years of education needed to understand a piece of writing and is widely used for checking health messages. However, the full text on the page discussing those features produces an unacceptably high SMOG readability score of 11.57

Examples of overly difficult—but certainly not the most difficult—text on this page include the phrase, “Is the most common form of dementia, a general term for the loss of memory and other intellectual abilities serious enough to interfere with daily life.” Other issues that the simple algorithm in the SMOG cannot discover include the assumption that people will understand that the subject matter is AD based on the context of the page alone. That is, AD is not specifically indicated as the subject in the sentence above, even though this is one of the key phrases on the page. Other vocabulary and embedded concepts that will challenge many adults include “form of dementia” and “intellectual abilities.” People may, for example, fully understand the simple word “form” but not be aware that dementia can have different “forms,” even if they have a basic understanding of dementia.

In addition, Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act requires that federal agencies' electronic and information technology be accessible to people with disabilities.36 A quick check of accessibility can be found by using the HiSoftware® Cynthia Says™ portal37 or equally proposed useful criteria.2,38

Scientific Literacy

Scientific jargon can present difficulties for laypersons. For example: “Plaques build up between nerve cells. They contain deposits of a protein fragment called beta-amyloid (BAY-tuh AM-uh-loyd).” Sentences such as these can help readers pronounce terms but not necessarily understand their meaning. In the attempt to define plaques and the role they play in AD, many other concepts are used without definition. There is no basis to believe that lay readers will have sufficient understanding of “nerve cells,” “deposits of a protein fragment,” or “beta-amyloid.” This comprehension is assumed to be present, and that assumption leaves many readers without an ability to incrementally increase their health literacy. Offering some means to acquire an understanding of the words would be a step toward providing readers with a scaffold of language from which they can begin building a more complete understanding of AD.

The AA website makes a solid attempt at explaining the state of the science around AD and the importance of continuing scientific investigation. This understanding will prove very helpful to people when the scientific understanding of today is changed by the scientific development of tomorrow. For example, while still at the nearly 10th-grade educational level on the SMOG, the intent of these sentences is in line with the scientific domain: “We’ve learned most of what we know about Alzheimer’s in the last 15 years. There is an accelerating worldwide effort underway to find better ways to treat the disease, delay its onset, or prevent it from developing.”

Civic Literacy

The civic literacy domain of health literacy includes the skills needed to successfully maneuver the power relationships that are inherent within the healthcare system and expressed—often only implicitly—in health communication. This section of the AA website does little to empower patients to actively participate or seek care. The strongest simple messages are in bold type, one of which is the previously mentioned phrase, “Has no current cure;” another is, “Is a progressive and fatal brain disease.” While there is brief mention of treatments, services, and support that can make life better, use of the words “no cure” and “fatal” can discourage rather than empower patients and their families seeking help. In this area of care especially, there is a very fine line between complete medical accuracy and empowerment. Ideally, both should remain possible to help patients and their caregivers maintain as high a quality of life as possible for as long as possible.

Cultural Literacy

Cultural literacy considerations are not applied as often as they are discussed. With regard to AD specifically, there are many cultural barriers to cross, even though the disease itself seems to be blind to racial and cultural differences. For instance, in segments of the Hispanic culture, barriers that may exist include a fear of social stigma, feelings about gossip being sinful, hesitancy to reveal personal matters, the use of folk medicine, and belief in the occult.39

The section of the AA website targeting “Professionals and Researchers” provides a collection of translated materials to help reach across cultures. Sections of the website target African-American, Latino/Hispanic, Chinese, Vietnamese, and Korean populations. The challenge is for individual practitioners and families to select these materials appropriately with regard to the specific individuals being addressed. For instance, there is tremendous variation within each of the broad groupings targeted by the AA website, and it would be improper for someone to assume that the materials, for instance, were equally appropriate to all Spanish speakers or all Chinese speakers.

Many written materials are available for use by healthcare professionals to provide their patients, such as the National Institutes of Health’s Understanding Alzheimer’s Disease, a patient education booklet released in 2006 that was specifically designed for individuals with low health literacy.40 This booklet addresses at least three of the four domains of health literacy fairly well, with the exception being cultural literacy. The booklet scores at grade 8.48 educational level on the SMOG but is available only in English, so it is limited in terms of cross-cultural applicability, especially when language is a primary consideration.

Other resources available include “Quick Guide to Health Literacy and Older Adults” published by The Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion,41 which provides a general overview of health literacy issues and includes a practical checklist about the usability of health information applicable to most patient education encounters (Table II). The National Institute on Aging has two publications that provide guidelines. One is for creating patient education materials (“Making Your Printed Health Materials Senior Friendly”42), and the other is for the patient to use in communicating with his or her physician (“Talking with Your Doctor”).43

Other useful websites include “Creating Plain Language Forms for Seniors,”44 “Clear and to the Point: Guidelines for Using Plain Language at NIH,”45 and “Clear & Simple: Developing Effective Print Materials for Low-Literate Readers.”46

Strategies for Lowering Health Literacy Barriers in Clinical Practice

Identifying patients with low health literacy in order to provide help can be challenging. In the outpatient or assisted living setting, behaviors signaling low literacy may include frequent missed appointments, not knowing the names or purposes of medicines, bringing someone else along to help because “I forgot my glasses,” eyes wandering over patient education handouts, being very slow to finish, sounding out words, looking confused, or putting written materials aside to “look at later.” In the LTC setting, it may be difficult if not impossible to distinguish between literacy problems and cognitive impairment.

However, addressing health literacy requires rigorous application of general techniques for good communication, whether in the outpatient or LTC setting. Online tools are available for training in health literacy.47 The mnemonic SPEAK (Speech, Perception, Education, Access, and Knowledge) provides a simple framework that healthcare professionals can use to enhance their own awareness of health literacy components during patient care.48 Since on-site staff will be present far more often than other healthcare professionals, it is very important to gain their cooperation in using strategies to help older adults comprehend their situation. Due to typically high staff turnover in LTC settings, system-level solutions are likely to have more impact than solving issues one patient at a time. Strategies that should be encouraged for all staff to use at all times include:

1. Bring up the subject. Shame about the inability to read or understand is often a significant barrier to improving or addressing health literacy issues, and providing a safe opportunity for the patient to do so is essential. Example questions and actions include:

- “What things do you like to read?”

- “We need help fixing the information we give to people; what do you think we could make better?”

- Ask patient to read prescription bottle if medications are being dispensed at the bedside or at the time of discharge from a facility.

- Conduct a brown bag medication review, paying particular attention to how the individual identifies medications—by reading the label or looking at the color and shape of the pills. Make sure the patient does the review and not the healthcare professional.

2. Limit information overload to maximize the chances of comprehension:

- Be concrete, and use the active voice.

- Start with the most important information first, and limit new information.

- Provide no more than one or two instructions at a time, and check on each as you go (use the teach-back technique).

- Use repetition, but not too much.

3. Be creative:

- Tape pills to a card, color-code medications, or draw a rising sun with other indications of morning to indicate taking them in the morning (eg, the AHRQ pill card).49

- Use physical objects and pictures to explain or demonstrate proposed procedures or activities in which the patient will be involved.

4. Ethically involve informal as well as formal caregivers:

- Pay attention to signage and navigation of your facility; do a Health Literacy “work-up” of the building to identify barriers to navigation and access.

- Also give instructions to family members when appropriate to age and cultural considerations.

- Create and use checklists for healthcare professionals to follow for all commonly conducted procedures.

- Get local volunteers to help. Many communities have adult literacy programs where volunteers act as tutors, show persons how to access Internet information, or assist persons with understanding complicated written materials. Good starting places are the local library or literacy organization.

Conclusion

Despite all barriers, it is essential to help older adults and their caregivers have the capacity to find, understand, evaluate, communicate, and use basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions. The health literacy skills of healthcare professionals is equally, if not more, important. Healthcare professionals must be willing to start by addressing their own skills and the barriers in healthcare settings, taking advantage of awareness-raising and training sessions in the workplace where available and online.47 Health literacy issues offer clear evidence that the healthcare system must accommodate change for our patients’ sake and for our own future healthcare needs. It is never too late to start.

Acknowledgments

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions they are affiliated with.

“Improving Health Literacy in Older Adults to Safeguard Patient Safety” was presented at the American Geriatrics Society Annual Meeting in Washington, DC, May 2008.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Kobylarz is Associate Professor, Center for Healthy Aging at Parker Stonegate, and is at the Department of Family Medicine, UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ; Dr. Pomidor is Associate Professor, Department of Geriatrics, Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee; and Dr. Pleasant is Assistant Professor, Department of Human Ecology, Extension Department of Family and Community Health Sciences, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick.