Epilepsy and the Elderly

Introduction

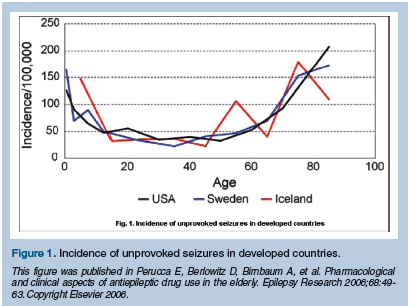

Although many consider epilepsy a condition of childhood, the highest incidence of new-onset epilepsy occurs in individuals over the age of 60 (Figure 1). Seizures can be either provoked or unprovoked. Metabolic disturbances and alcohol withdrawal are common causes of acute provoked seizures, and treatment is directed towards the underlying provoking medical condition. In contrast, the diagnosis of epilepsy is made when a patient experiences recurrent unprovoked seizures. In this short review, issues surrounding acute provoked seizures in the geriatric population will not be discussed. Instead, we will address: (1) the type of epilepsy older individuals experience, (2) the causes of new-onset epilepsy in the elderly, (3) the diagnostic evaluation of the older patient with spells of alteration in level of consciousness, and (4) the treatment of epilepsy in the elderly. The older antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), especially phenobarbital and phenytoin, have recently fallen out of favor for treatment of the elderly, primarily because of their side-effect profile. Many neurologists advocate the use of the newer AEDs (eg, lamotrigine, gabapentin) since they are effective and better tolerated in the older individual with a seizure disorder.

Types of Seizures

One of the major developments in the field of epilepsy has been the adoption of the International Classification of Epileptic Seizures (ICES), which recognizes two major categories of seizures: those that begin locally in a specific region of the brain and then spread (partial seizures); and those that are widespread with no identifiable focal origin at onset (generalized seizures).1 In contrast to children who commonly present with generalized seizures, the majority of older individuals who develop new-onset epilepsy experience partial seizures. Partial seizures are subdivided based on the impact of the seizure on consciousness. Simple partial seizures are typically brief (less than a minute) and consciousness is preserved, although communication skills may be impaired. During a simple partial seizure, a patient may experience abnormalities of movement (eg, twitching), emotions (eg, fear), or sensations (eg, visual disturbances) that correspond to the affected region of the brain. In the past, the term aura was used to describe the simple partial seizure, or warning, sensed by some patients before the loss of consciousness experienced with spread of the abnormal epileptic discharge in the brain and evolution to a complex partial seizure. During a complex partial seizure, consciousness is altered. Typically, complex partial seizures last 1-3 minutes and involve a larger area of the brain. Often starting with a blank stare, patients can develop nonpurposeful movements (automatisms), such as chewing or fumbling with objects. Confused and frequently still ambulatory, these patients are at risk for falls and injuries. Partial seizures can spread and evolve into generalized tonic clonic seizures (previously called grand mal seizures). Status epilepticus, defined as continuous seizure activity or multiple seizures without a return of consciousness, is almost twice as common in the elderly than in younger adults and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.2,3

Etiology of Seizures

It is not surprising that partial seizures are the most common type of seizures in the elderly, since stroke is the most commonly identified cause of new-onset epilepsy in the geriatric population. Risk factors for the development of post-stroke epilepsy include hemorrhage, cortical involvement, and a history of acute symptomatic seizures.4 Unfortunately, there is no way of determining which stroke patients will develop epilepsy, and there is no role for prophylactic AED therapy. Degenerative disorders, head trauma, and tumor (both primary and metastatic) are the other most frequently identified etiologies of new-onset seizures in the elderly. Alzheimer’s disease is a risk factor for epilepsy, and between 9% and 16% of patients with Alzheimer’s disease will develop a seizure disorder, typically in the later stages of the illness.5-7 Despite recent advances in neuroimaging, one-third to one-half of older patients experience cryptogenic seizures, where the exact cause is unknown.8-12 Some researchers propose that central nervous system (CNS) vascular disease is the cause of most of the cryptogenic cases since stroke risk factors (hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, coronary artery disease, and peripheral vascular disease) are associated with seizures, in the absence of stroke on neuroimaging studies.13,14 If possible, identification of the cause of new-onset epilepsy in the elderly is important since it might diagnose a treatable and previously unidentified neurological and/or systemic illness. In addition, determining the etiology and type of seizures in an elderly individual with new-onset epilepsy will help determine future medical and neurological interventions for that patient.

Clinical Diagnosis

Frequently, it is difficult to establish the diagnosis of epilepsy in the older individual. As already discussed, most seizures in elderly patients are focal in onset, and seizures may be less obvious than in younger individuals.9,15-17 The possibility of seizures should be considered in any older individual who presents with intermittent confusional states. It has been suggested that symptoms during a seizure may be atypical in elderly patients because the seizure focus is often extra-temporal,18 making the clinical diagnosis even more challenging. The healthcare provider needs to interview not only the patient about his or her symptoms, but any available witnesses who have seen the individual’s spells of alteration in level of consciousness. The older patient may not experience a classic aura (eg, déjà vu, olfactory hallucination) associated with temporal lobe seizures.17,19 Instead, older patients tend to report nonspecific changes before loss of consciousness, such as lightheadedness, dizziness, and muscle cramps. Witnesses will describe episodic confusion accompanied by a blank stare, clumsiness, or unorganized movements. Postictal confusion is frequently longer (hours) in duration than is witnessed in younger patients. Often, the diagnosis of epilepsy is not established until the patient has a secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizure.

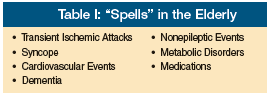

The first clinical consideration that needs to be addressed is whether the patient has had an epileptic seizure. The differential diagnosis for spells of alteration in level of consciousness in the elderly is broad (Table I) and includes transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) and syncope.

The first clinical consideration that needs to be addressed is whether the patient has had an epileptic seizure. The differential diagnosis for spells of alteration in level of consciousness in the elderly is broad (Table I) and includes transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) and syncope.

Transient ischemic attachs usually present with negative symptoms that are not often seen with seizures, such as numbness and weakness. In addition, although a TIA can cause focal neurological symptoms, it is not typically associated with generalized confusion. During a TIA, motor symptoms consist of weakness. During a seizure, motor symptoms are more often associated with repetitive movements. The duration of the spell can prove a helpful distinguishing tool since seizures typically last no more than 3 minutes, whereas TIA symptoms last longer (minutes to hours).20

Syncope, especially cardiogenic syncope, should be considered in the differential diagnosis for epilepsy. Questions regarding pallor, palpitations, diaphoresis, chest discomfort, and dyspnea frequently provide additional clues indicative of a cardiovascular event. The development of lightheadedness, dizziness, nausea, and fatigue upon standing or sitting upright suggest orthostatic intolerance, and serve as clinical clues to the diagnosis of syncope. It is important for the clinician to remember that syncope can be accompanied by brief clonic activity due to brain hypoperfusion. In contrast to seizure activity, muscle twitching with syncope is mostly clonic or myoclonic (not tonic) and involves the distal extremities (not axial). While rare with syncope, injury, such as tongue or cheek biting, is common with seizures. People with convulsions often fall forward or backward during the phase of tonic rigidity, sustaining injury to the forehead, chin, or occipital area. Headache, confusion, and urinary incontinence are common with seizures, but rare with syncope. Focal neurological findings on examination are sometimes present with seizures, but not with syncope.20,21

Diagnostic Evaluation

If the spells are epileptic in nature, the examination should search for provoking factors. Seizures caused by metabolic disturbance (eg, hypoglycemia), medications (eg, bupropion), medication withdrawal (eg, benzodiazepines), or substance abuse (eg, alcohol) are treated by addressing the underlying medical issue; AED treatment is typically not prescribed. Since both toxicity and metabolic abnormalities can provoke seizures and lower seizure threshold in patients with epilepsy, patients with acute seizures should have a toxicology screen and serum analyzed for electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, glucose, calcium, magnesium, and liver function tests. Since AED therapy is an option, a simultaneous analysis of a complete blood count, differential, and platelets can provide baseline data. Because stroke is the most common etiology for new-onset epilepsy in the elderly, laboratory evaluation for risk factors (eg, hemoglobin A1C, lipid panel) should be considered.

Since a structural lesion is the most common cause of epilepsy in the elderly, neuroimaging studies should be obtained. A computed tomography (CT) scan may be of value in an emergency setting to assess for a focal mass that requires emergent intervention (eg, intracranial hemorrhage, tumor). In a recent study investigating the treatment of epilepsy in the elderly, only 18% of patients had normal CT scans of the brain.22 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast should be pursued in most cases, especially if the older individual has complaints suggesting a focal abnormality, or has a focal neurological exam or an abnormal electroencephalogram (EEG) suggestive of a partial seizure disorder caused by a CNS structural lesion.

An electro-clinical seizure on EEG confirms the diagnosis of epilepsy in an individual with stereotypical spells, but these are rarely recorded during the course of a routine EEG. Interictal epileptiform abnormalities (eg, sharp waves, spikes, polyspikes) are suggestive of a seizure tendency. An EEG performed while a patient is asleep, as well as during wakefulness, increases the diagnostic yield of the EEG. It is important to remember that a normal EEG does not eliminate epilepsy as a diagnosis. To further complicate the issue, the frequency of interictal epileptiform discharges on EEG diminish with increasing age.18,23,24 Closed-circuit television (CCTV) - EEG monitoring, which has proven invaluable in the diagnosis and classification of epileptic syndromes in younger patients, tends to be underused in the elderly population. This is true despite the fact that events attributable to treatable medical conditions and nonepileptic “psychogenic” seizures have been described in the older population.25-28

Treatment

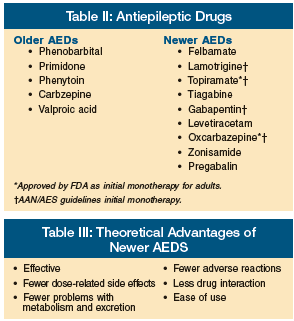

Although neurosurgical intervention and vagal nerve stimulation are options in the treatment of older adults with refractory seizures,29,30 medications remain the mainstay of therapy for epilepsy in the geriatric population. AEDs are classically separated into the older/established AEDs and the newer AEDs that have primarily been approved by the FDA as add-on therapy to the older agents (Table II). Despite lack of FDA approval, many clinicians use the newer agents as monotherapy for treatment of new-onset epilepsy because of their theoretical advantages (Table III).

Although neurosurgical intervention and vagal nerve stimulation are options in the treatment of older adults with refractory seizures,29,30 medications remain the mainstay of therapy for epilepsy in the geriatric population. AEDs are classically separated into the older/established AEDs and the newer AEDs that have primarily been approved by the FDA as add-on therapy to the older agents (Table II). Despite lack of FDA approval, many clinicians use the newer agents as monotherapy for treatment of new-onset epilepsy because of their theoretical advantages (Table III).

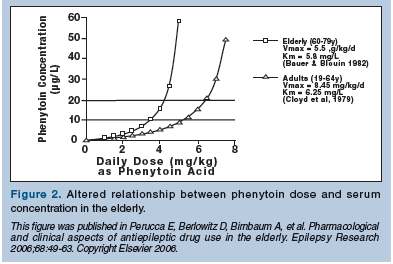

The normal aging process has a considerable influence on the pharmacokinetics of drugs in the elderly. Physiological alterations associated with aging that impact the metabolism of AEDs include decreased plasma protein binding, increased volume of distribution, decreased hepatic drug metabolism and renal clearance, and altered gastrointestinal absorption.31,32 Pharmacokinetic problems are more likely to occur with the older, established agents that are more highly protein-bound, more commonly hepatically metabolized, and renally excreted.31,33 Antiepileptic drug treatment is further complicated in geriatric patients with epilepsy since they are often taking other medications for concurrent diseases.34 Many AEDs impact metabolizing enzymes, and induction and inhibition of these systems can lead to clinically significant drug interactions. The theoretical advantages of the newer AEDs, in conjunction with published clinical trials,22,35 have led many experts to consider several of the newer AEDs as optimal treatment for older individuals with epilepsy.36-38 In addition, phenobarbital and phenytoin are now believed by many epilepsy experts to be “suboptimal” AEDs for older patients due to their side-effect profiles and potential for drug interactions. While it is possible that some patients may have good seizure control with low-dose phenobarbital, the associated adverse effects (eg, cognitive decline, forgetfulness, gait disturbance) led the U.S. National Committee on Quality Assurance to identify phenobarbital as a drug to be avoided in the elderly.39 Phenytoin’s nonlinear kinetics can result in a narrowed therapeutic window.40 In addition, in older individuals, a small increase in dose or altered absorption can result in a broad variability in phenytoin serum levels, leading to potential toxicity or breakthrough seizure activity (Figure 2).

In one study of elderly nursing home residents, phenytoin levels were highly variable, even when doses were unchanged and medication administration was regulated.41 Clinicians must also remember that phenytoin is a highly protein-bound AED. A routine serum phenytoin level is a total level that represents the sum of the protein-bound phenytoin and the protein unbound (or “free”) phenytoin in the blood. It is the “free” phenytoin that enters the brain, controls seizures, and can produce neurotoxic side effects. In older individuals with low albumin levels, the free-drug level may be increased relative to the total level and lead to dose-related toxicity. Measuring free phenytoin levels may provide a more effective guide to dose adjustment than routine total serum phenytoin levels. Despite recommendations, phenytoin remains the most widely prescribed AED in the United States and is commonly used in the geriatric population, including nursing home residents.42,43

Several international neurological organizations have established recommendations or guidelines for the treatment of epilepsy in children and adults, but few specifically address the treatment of the geriatric population with epilepsy.36,44,45 This is because only a few clinical trials specifically studied AED treatment in the elderly.46 A recent review by the International League Against Epilepsy47 identified only two randomized studies that examined the efficacy and tolerability of AED therapy in the elderly.22,35 In those two studies, elderly patients were randomized to different AED treatments. As with many AED clinical trials, the primary study outcome measure was retention of subjects over a period of time (1-2 yr). Retention rates, or the number of patients who completed the study, reflect both withdrawal due to either intolerable side effects or inadequate seizure control. Both studies found that older patients were more likely to withdraw because of side effects and advocated the use of lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy over "rapid-release" carbamazepine in older patients with new-onset epilepsy. Because drug toxicity, not drug efficacy, was the major cause for patient withdrawal in these studies, "extended-release" carbamazepine remains an epilepsy treatment option in elderly patients. Starting at a low dose and titrating the AED slowly is strongly advocated by experts.46

Conclusion

Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder in elderly persons. Partial seizures (both simple and complex) are the most frequent seizure type and can be difficult to diagnose. Obtaining a precise history, including events observed by witnesses, is invaluable. Video EEG monitoring may prove diagnostically useful. Phenobarbital and phenytoin are suboptimal AEDs for new-onset epilepsy in the elderly. Newer agents (lamotrigine and gabapentin) and extended-release carbamazepine should be considered as treatment options.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Acknowledgements This paper was funded by VA Health Services Research and Development Service, IIR 02-274 (Dr. Pugh PI). The authors acknowledge and appreciate support from the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, along with the South Texas Veterans Healthcare System/Audie L. Murphy Division and the VERDICT research program. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

1. Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia 1989;30(4):389-399.

2. Cloyd J, Hauser W, Towne A, et al. Epidemiological and medical aspects of epilepsy in the elderly. Epilepsy Res 2006;68(Suppl 1):39-48. Epub 2005 Dec 27.

3. Waterhouse EJ, DeLorenzo RJ. Status epilepticus in older patients: Epidemiology and treatment options. Drugs Aging 2001;18(2):133-142.

4. Lancman ME, Golimstok A, Norscini J, Granillo R. Risk factors for developing seizures after a stroke. Epilepsia 1993;34(1):141-143.

5. Hauser WA, Morris ML, Heston LL, Anderson VE. Seizures and myoclonus in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1986;36(9):1226-1230.

6. McAreavey MJ, Ballinger BR, Fenton GW. Epileptic seizures in elderly patients with dementia. Epilepsia 1992;33(4):657-660.

7. Hesdorffer DC, Hauser WA, Annegers JF, et al. Dementia and adult onset unprovoked seizures. Neurology 1996;46(3):727-730.

8. Ramsay RE, Rowan AJ, Pryor FM. Special considerations in treating the elderly patient with epilepsy. Neurology 2004;62(5 Suppl 2):S24-S29.

9. Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Kurland LT. Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935-1984. Epilepsia 1993;34(3):453-468.

10. Loiseau J, Loiseau P, Duche B, et al. A survey of epileptic disorders in southwest France: Seizures in elderly patients. Ann Neurol 1990;27(3):232-237.

11. Stephen LJ, Brodie MJ. Epilepsy in elderly people. Lancet 2000;355(9213):1441-1446.

12. Bergey GK. Initial treatment of epilepsy: Special issues in treating the elderly. Neurology 2004;63(10 Suppl 4):S40-S48.

13. Li X, Breteler MM, de Bruyne MC, et al. Vascular determinants of epilepsy: The Rotterdam Study. Epilepsia 1997;38(11):1216-1220.

14. Ng SK, Hauser WA, Brust JC, Susser M. Hypertension and the risk of new-onset unprovoked seizures. Neurology 1993;43(2):425-428.

15. Hiyoshi T, Yagi K. Epilepsy in the elderly. Epilepsia 2000;41(Suppl 9):31-35.

16. Rowan AJ, Kelly KM, Bergey GK, Birnbaum AK. Epilepsy later in life: Managing the unique problems of seizures in the elderly. Geriatrics 2005;60(Suppl):3-21.

17. Tinuper P, Provini F, Marini C, et al. Partial epilepsy of long duration: changing semiology with age. Epilepsia 1996;37(2):162-164.

18. Ramsay RE, Pryor F. Epilepsy in the elderly. Neurology 2000;55(5 Suppl 1):S9-S14; S54-S58.

19. Kellinghaus C, Loddenkemper T, Dinner DS, et al. Seizure semiology in the elderly: A video analysis. Epilepsia 2004;45(3):263-267.

20. Sirven JI. Acute and chronic seizures in patients older than 60 years. Mayo Clin Proc 2001;76(2):175-183.

21. Leppik IE. Contemporary Diagnosis and Management of the Patient With Epilepsy. 6th ed. Newton, PA: Handbooks in Health Care; 2006.

22. Rowan AJ, Ramsay RE, Collins JF, et al; VA Cooperative Study 428 Group. New onset geriatric epilepsy: A randomized study of gabapentin, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine. Neurology 2005;64(11):1868-1873.

23. Marsan CA, Zivin LS. Factors related to the occurrence of typical paroxysmal abnormalities in the EEG records of epileptic patients. Epilepsia 1970;11:361-381.

24. Drury I, Beydoun A. Interictal epileptiform activity in elderly patients with epilepsy. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1998;106(4):369-373.

25. Drury I, Selwa LM, Schuh LA, et al. Value of inpatient diagnostic CCTV-EEG monitoring in the elderly. Epilepsia 1999; 40(8):1100-1102.

26. Lancman ME, O'Donovan C, Dinner D, et al. Usefulness of prolonged video-EEG monitoring in the elderly. J Neurol Sci 1996;142(1-2):54-58.

27. Duncan JS, Sander JW, Sisodiya SM, Walker CM. Adult epilepsy. Lancet 2006;367(9516):1087-1100.

28. Behrouz R, Heriaud L, Benbadis SR. Late-onset psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav 2006;8(3):649-650. Epub 2006 Mar 13.

29. Grivas A, Schramm J, Kral T, et al. Surgical treatment for refractory temporal lobe epilepsy in the elderly: Seizure outcome and neuropsychological sequels compared with a younger cohort. Epilepsia 2006;47(8):1364-1372.

30. Sirven JI, Malamut BL, O'Connor MJ, Sperling MR. Temporal lobectomy outcome in older versus younger adults. Neurology 2000;54(11):2166-2170.

31. Perucca E, Berlowitz D, Birnbaum A, et al. Pharmacological and clinical aspects of antiepileptic drug use in the elderly. Epilepsy Res 2006;68(Suppl 1):S49-S63. Epub 2005 Oct 3.

32. Gidal BE. Drug absorption in the elderly: Biopharmaceutical considerations for the antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsy Res 2006;68(Suppl 1):65-69. Epub 2006 Jan 18.

33. Faught E. Epidemiology and drug treatment of epilepsy in elderly people. Drugs Aging 1999;15(4):255-269.

34. Lackner TE, Cloyd JC, Thomas LW, Leppik IE. Antiepileptic drug use in nursing home residents: Effect of age, gender, and comedication on patterns of use. Epilepsia 1998;39(10):1083-1087.

35. Brodie MJ, Overstall PW, Giorgi L. Multicentre, double-blind, randomised comparison between lamotrigine and carbamazepine in elderly patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy. The UK Lamotrigine Elderly Study Group. Epilepsy Res 1999;37(1):81-87.

36. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Diagnosis and management of epilepsy in adults. Accessed October 15, 2007.

37. Semah F, Picot MC, Derambure P, et al. The choice of antiepileptic drugs in newly diagnosed epilepsy: A national French survey. Epileptic Disord 2004;6(4):255-265.

38. Karceski S, Morrell MJ, Carpenter D. Treatment of epilepsy in adults: Expert opinion, 2005. Epilepsy Behav 2005;7( Suppl 1):S1-S64.

39. NCQA. HEDIS 2006 draft NDC lists public comment--September 2-30. Accessed October 15, 2007.

40. Cloyd JC. Commonly used antiepileptic drugs: Age-related pharmacokinetics. In: Rowan AJ, Raqmsey RE, eds. Seizures and Epilepsy in the Elderly. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann;1997:219-227.

41. Birnbaum A, Hardie NA, Leppik IE, et al. Variability of total phenytoin serum concentrations within elderly nursing home residents. Neurology 2003;60(4):555-559. [Erratum in: Neurology 2003;60(10):1727.]

42. Ruggles KH, Haessly SM, Berg RL. Prospective study of seizures in the elderly in the Marshfield Epidemiologic Study Area (MESA). Epilepsia 2001;42(12):1594-1599.

43. Pugh MJ, Cramer J, Knoefel J, et al. Potentially inappropriate antiepileptic drugs for elderly patients with epilepsy. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52(3):417-422.

44. French JA, Kanner AM, Bautista J, et al; Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology; Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology; American Epilepsy Society. Efficacy and tolerability of the new antiepileptic drugs I: Treatment of new onset epilepsy: Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee and Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology 2004;62(8):1252-1260.

45. National Collaborating Center for Primary Care. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence. The epilepsies: the diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2004. Accessed December 3, 2007.

46. Leppik I. Antiepileptic drug trials in the elderly. Epilepsy Res 2006;68(1):45-48.

47. Glauser T, Ben-Menachem E, Bourgeois B, et al. ILAE treatment guidelines: Evidence-based analysis of antiepileptic drug efficacy and effectiveness as initial monotherapy for epileptic seizures and syndromes. Epilepsia 2006;47(7):1094-1120.