Impact of Dementia Caregiving on the Caregiver in the Continuum of Care

INTRODUCTION

Dementia caregiving, perhaps more than other types of caregiving, tremendously burdens the physical, psychological, social, and financial world of the 4 million caregivers providing informal care to elderly persons with dementia. Compared with care recipients without dementia, persons with dementia are more likely to be older, take medications, and require services, such as transportation, mobile meals, adult day care, and medication management.1 In-home care and accompanying services may be needed for 6.5 years, and most patients with dementia are placed in a nursing home.2 Features of dementia that exacerbate the caregiving burden include a lack of patient insight, changes in personality, disruptive behaviors as the disease progresses, inadequacies in caregiver social support, and difficulties in locating resources. Additionally, caregivers trying to deal with disruptive behavior in an elderly person with dementia may be at risk for physical harm. Inadequate support of the caregiver may result in unnecessarily higher levels of caregiver depression and stress, incomplete treatment of patient symptoms, and in extreme cases, patient neglect or abuse.

An important task of the geriatrics health care provider is to recognize caregiver stress and identify resources for the caregiver to alleviate or share the burden. Most dementia caregivers are married, half of them work full-time, 59% are female, and half of them are age 50 years or older.1 Of every four of these caregivers, three have unmet needs.1 Anticipating these needs by understanding factors modulating the impact of dementia caregiving may help clinicians identify caregiver stress and individualize treatment for both patients and their caregivers. This article provides an overview of these factors, as well as suggestions for clinicians to help them support caregivers at different stages of caregiving and throughout the continuum of care.

CAREGIVING IN THE COMMUNITY

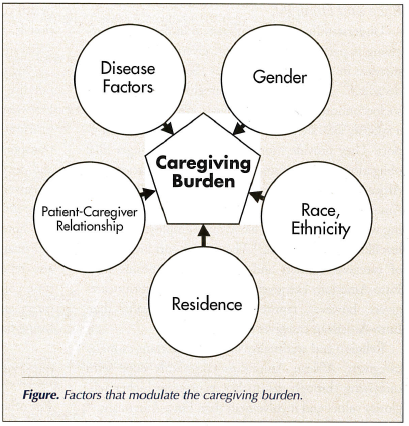

A paradigm for understanding the factors that modulate the caregiving burden is depicted in the Figure. The impact of each factor on caregiving burden is described below.

Disease Factors in the Care Recipient

Caregivers of persons with moderate-to-severe dementia have higher burden indices, particularly in areas of loss of control, as compared with caregivers of persons with more mild dementia.3,4 This is not surprising since many behavior disturbances are more common as the disease progresses. Behavior disturbance, as well as poor perceived caregiver health and fewer informal social supports, are implicated in other studies of increased caregiver burden.5-7

Caregivers find aggression—compared with wandering, delusions, and incontinence—the most distressing behavioral disturbance of patients with dementia.8 Disruptive behavior, particularly violence, is also a predictor of caregiver violence, and spouses may be more likely to engage in violence than other relatives.9 In one study, predictors of caregiver violence included disruptive patient behavior, poor quality of social support for the caregiver, poor involvement of the caregiver in a social network, and a poor premorbid relationship.10 Caregivers may also be subjected to violence. Within one year of diagnosis, 15.8% of care recipients in an Alzheimer’s disease registry were violent toward the caregiver; 5.4% of caregivers were violent toward the care recipient; and 3.8% were mutually violent.11 The variables most associated with violence were caregiver depression and (shared) living arrangement.

Patient–Caregiver Relationship

The most common relationship in dementia caregiving is between parent (usually mother) and child (usually daughter).1 Research suggests that spouses provide care with fewer supports, and often in the face of tension when their expectations and plans differ from those of other family members. For example, it is not uncommon for the child of a caregiver to encourage placement when the spouse is not ready to institutionalize the elderly person with dementia. Spouses with more sense of control may be less likely to have depressive symptoms.12 Daughter (and daughter-in-law) caregivers may have different challenges. There may be conflicting demands between care for the parent, care of minor children, and employment outside the home. Old conflicts with the parent may also resurface and cause stress.

Gender

Female spouses, daughters, and daughters-in-law constitute the majority of caregivers, although the number of male spousal and male child caregivers continues to rise.13 Wives and daughters report higher scores on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale than husbands in the areas of relational deprivation, loneliness, and depression.14 Reasons for these scores are unclear, but may include use of less effective coping strategies15 and outlook on caregiving.16-18

Race and Ethnicity

Understanding ethnic differences in dementia caregiving is particularly important, given the anticipated increase in older minorities over the next two to five decades.19 Ethnic minority caregivers are of lower socioeconomic status, are younger, are less likely to be a spouse, and are more likely to receive informal support. They provide more care and have stronger filial obligation beliefs than Euro-American caregivers.20 African-American caregivers are more likely than Euro-Americans, Hispanics, and Asians to have children living with them, are more likely to be employed, and are less likely to be married.21 They also report lower levels of caregiver burden and depressive symptoms than Euro-American caregivers.20 All ethnic minority caregivers, however, report worse physical health than Euro-American caregiver counterparts.

Religion and spirituality may be important to many caregivers. African Americans commonly cope with caregiving through spirituality, expressing higher religiosity values and involvement than Euro-Americans.22 Moreover, it appears that African Americans not only appraise aspects of caregiving as less stressful than Euro-Americans, but they may also derive more benefit and meaning from the experience.23,24 Latino caregivers also express higher religiosity and stronger views on filial support, as compared to Euro-Americans.25

Little is known about dementia and dementia caregiving in the American-Indian (AI) and Alaska-Native (AN) populations. As with other minorities in the U.S., native caregivers appear to draw upon cultural resources (eg, beliefs, extended families, and traditional religious practices). However, the poverty of rural native communities, lack of caregiver support, and prevalence of alcohol abuse may place native elders at risk for being financially exploited or physically abused by impoverished and substance-dependent relatives. There may also be substantial differences between tribes or between urban and rural AIs or ANs.26

Community of Residence

Rural caregivers may have higher degrees of stress than urban caregivers, although comparative data are sparse. Rural caregivers perceive a lack of specialized health care and access to geriatrics health care professionals, a greater sense of social isolation, and a lack of social support.27

Slightly more than half of dementia caregivers do not live with the person for whom they are caring. However, they may provide a great deal of support with instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), such as transportation, shopping, medication management, and doctors’ visits.1 Additional stressors arise when the caregiver resides a distance from the care recipient. Long-distance caregivers, defined as living more than one hour away, report stress in gaining access to and information about formal services.28,29 These caregivers also report financial burdens due to frequent travel, time conflicts that disrupt intimate relationships and career, and unique emotional issues related to the toll of caring for their loved ones.28

IDENTIFICATION OF THE AT-RISK CAREGIVER

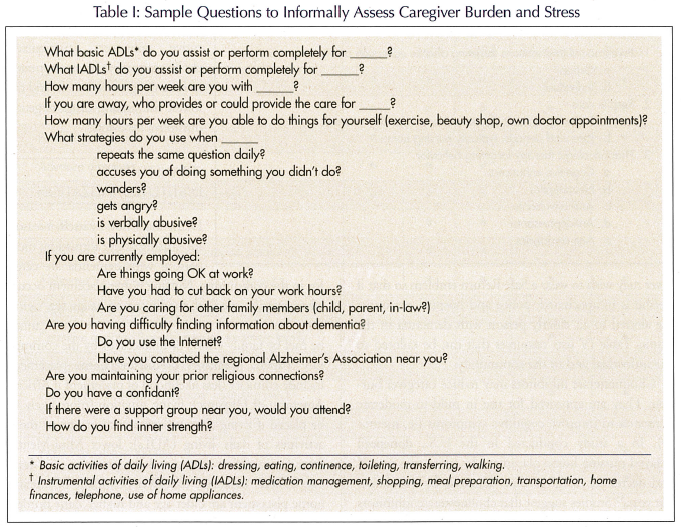

The office assessment of caregiver stress and burden can include validated tools, such as the modified Caregiver Strain Index30 or the Caregiver Burden Inventory,31 to identify an at-risk caregiver. However, targeted, practical questions posed to the caregiver may be just as helpful (Table I). These questions reflect the most frequently unmet needs of caregivers.21 Additionally, a caregiver may neglect his or her own health. Health problems may be medical (hypertension, diabetes), psychological (depression, anxiety), financial (inability to pay for medications), or early dementia. Timely referral of the caregiver to appropriate services may be essential to the health of the care recipient, and may prevent a crisis from developing.

INTERVENTIONS

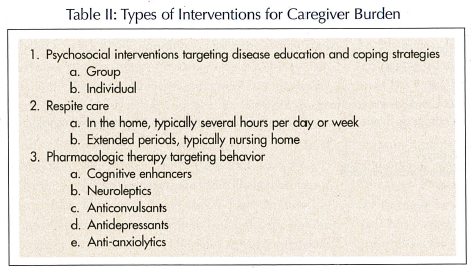

Table II lists types of interventions for caregiver burden. Psychosocial interventions may reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety, and improve life satisfaction.32 Interventions tailored to the individual may be more effective than group interventions. Respite care in a variety of settings and for varying durations has been shown to be helpful in some studies. Providing accurate and useful sources of educational information is important as well. Approximately 40% of caregivers turn to health care professionals for information, and nearly 30% turn to the Internet.1 Useful websites include the Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org) and the National Alliance for Caregiving (www.caregiving.org), which have reference material for both patients and physicians.

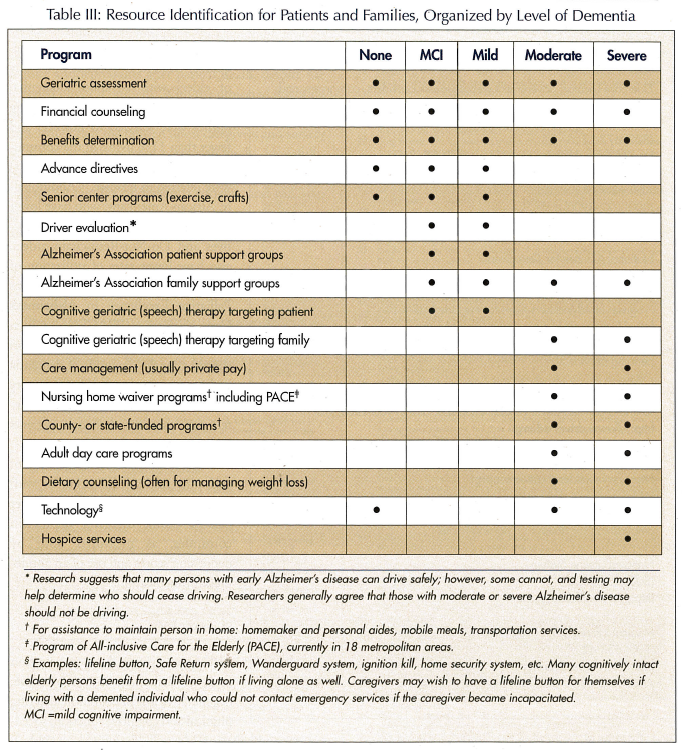

Table III lists resources that can be suggested for different stages of dementia, reflecting services that caregivers report they use.1 Interventions for early dementia (Clinical Dementia Rating [CDR] scale33 score, 0.5 or 1) target the patient, particularly in the areas of advance directives, senior programs, memory education, and driver evaluation. A skilled speech therapist specializing in cognitive skills may be able to help a mildly impaired elderly person maintain function by addressing communication and problem-solving skills.

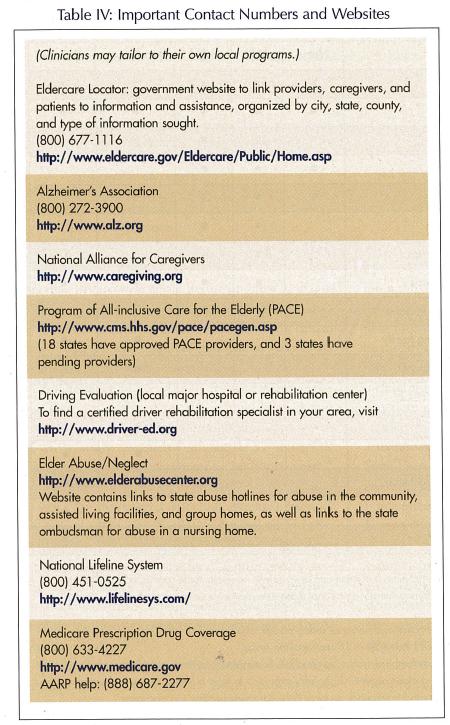

In moderate (CDR 2)-to-severe (CDR 3) dementia, interventions may focus on both the patient and the caregiver. Speech therapy may be helpful for the caregiver to learn coping strategies and problem-solving techniques to assist with communication to help reduce patient frustration and resultant behavior problems. Community or private services may be obtained to assist elderly persons in the home or help them find and attend a day care program. The Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) is particularly effective for caregiving families who are balancing employment and elder care. Devices can be purchased to help keep the patient safe, including an ignition kill for a persistent driver, the Wanderguard system, and a lifeline button. The lifeline button may be more useful for the caregiver in case of his/her own fall, if the care recipient is not able to call for help. Similarly, the caregiver may wish to wear a Safe Return emblem so that if he/she is incapacitated, police and hospital personnel are alerted to an elderly person with dementia in the home. Table IV lists resources that can be tailored to the individual and to the community.

Cholinesterase inhibitors may reduce caregiver burden. They are approved for use in mild-to-moderate dementia to improve cognitive symptoms (ie, memory). In a study conducted in the U.S., donepezil delayed nursing home placement by up to two years34 and decreased caregiver time demands by 400 hours per year.35 Studies suggest that cholinesterase inhibitors also reduce institutionalization risk, including combined cholinesterase inhibitors,36 tacrine37 (no longer in clinical use), and rivastigmine.38 Controversies continue since a study performed in the U.K. did not demonstrate a benefit to donepezil in delaying a combined endpoint of nursing home placement and progression of disability.39

Clinicians are often pressured to prescribe medications targeting behavior problems in elderly persons with dementia. A systematic review highlighted the lack of effectiveness of typical antipsychotics and the minimal benefits of atypical antipsychotics. Even these benefits may be offset by risks of ischemic cerebrovascular events and a higher rate of death.40 Antidepressants are helpful when depression underlies the behavior problem. One antidepressant, citalopram, appeared to be effective in managing agitation in the absence of a diagnosis of depression. Benzodiazepines may have more risk than benefit (falls, confusion), and anticonvulsants were not consistently effective. The cognitive enhancers, particularly cholinesterase inhibitors, appeared to have the greatest benefit and the lowest risk among drugs targeting disruptive behaviors.

TRANSITION TO INSTITUTIONALIZATION

Dementia is not, by itself, a reason for nursing home admission; most persons with dementia are cared for in the community. Nursing home placement occurs when specific medical conditions or needs (eg, agitation, incontinence, special therapy for a wound) cannot be met by family efforts or finances, or by the community. Patient predictors of nursing home placement include ethnicity (less likelihood of placement if African American or Hispanic); living situation (more likely to be placed if living alone); dependency in one or more activities of daily living (ADLs); lower Mini-Mental State Examination scores; and the presence of at least one difficult behavior. Caregiver predictors of nursing home placement are older age and higher Zarit Burden Interview score.41

After institutionalization, caregivers—particularly spouses—continue to feel distressed by the suffering and decline of their loved ones. The caregiver also has new challenges, such as frequent trips to the nursing home and reduced control over the care provided to the relative. Caregivers continue to have symptoms of anxiety and depression comparable to those experienced prior to admission.42

TRANSITION TO END-OF-LIFE CARE

More than two-thirds of elderly persons with dementia die in a nursing home, as compared with only one-quarter of elderly persons with cancer.43 Symptoms developing at the end of life for an elderly person with dementia, such as dyspnea, skin breakdown, agitation, and difficulty swallowing, may be more common than pain.44

Managing patient symptoms may add to caregiver stress for the relatively few caregivers with a terminally ill elderly individual with dementia living at home. In the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) study, one-half of family caregivers of persons with dementia in their last year of life spent at least 46 hours per week assisting patients with the basic ADLs and IADLs; more than half felt that they were “on duty” 24 hours a day, 7 days a week; and more than half felt that they had to end or reduce employment due to the demands of caregiving.45 Thus, caring for elderly persons with dementia living at home at the end of life may intensify psychosocial, economic, and physical burdens.

Studies of caregiver perceptions of care at the end of life, for elderly persons with and without dementia, suggest that hospice is helpful in the dying process, improves quality of life, reduces terminal symptoms, and may delay institutionalization.46-48 Hospice also provides support to the caregiver after the death of the care recipient. However, persons with dementia are infrequently referred to hospice. In a study of elders with advanced dementia, fewer than 6% residing in nursing homes were referred to hospice, and fewer than 11% living in the community (receiving health care services) were referred to hospice.49 Additionally, African Americans, who have lower rates of utilization of advance directives and Do-Not-Resuscitate orders, also have lower rates of utilization of hospice in general.50 Programs such as Palliative Excellence in Alzheimer’s Care Efforts (PEACE)51—which introduces the concept of palliation shortly after the diagnosis of dementia and focuses on the needs of minority families—may lead to higher quality terminal care for dementia patients and their caregivers.

The burden of depression does not end with institutionalization or with the death of the patient. Even after patient death, caregiver depression continues, as measured both by depression scores and use of an antidepressant medication.45,52

SUMMARY

Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, is a progressive, degenerative loss of cognition affecting physical and cognitive function, socialization, and behavior. Most elderly individuals wish to live at home as long as possible. As functional impairment increases during the course of dementia, caregivers require more assistance and access to resources. Behavioral symptoms are a cause of nursing home placement, and management of these symptoms helps defer institutionalization. Home hospice appears to be a program that is able to manage end-of-life symptoms and keep an elderly person with dementia at home longer. Depressive symptoms persist at a high level in caregivers even after institutionalization, and many require antidepressants after patient death, despite the lessened physical burdens. With the projected doubling of the older population over the next 25 years,19 it is anticipated that the burden upon caregivers and society as a whole will increase correspondingly. Hopefully, funding and services will grow correspondingly to fill in gaps for families of dementia patients, and will integrate caregiver support into federal and state health care and long-term care systems.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.