Comparing Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration: Implications for Long-Term Care

The cognitive impairments and behavioral symptoms associated with dementia have a progressive, negative impact on self-care abilities. Difficulty in managing self-care tasks, cognitive impairment, and the presence of one or more difficult behaviors are associated with long-term placement.1 It is estimated that approximately two-thirds of people residing in long-term care facilities are diagnosed with a dementing illness.2 As many as 90% of persons with dementia become institutionalized before death.3 Providing care to this population presents tremendous challenges. While much has been learned about Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common cause of dementia, less is known about frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). This article will explore differences that exist between the two types of dementia. Implications for long-term care are great, as many people with FTLD will require this type of care.

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia and is largely characterized as a cognitive disorder. The areas of the brain affected by AD produce common first symptoms of short-term memory loss, word-finding difficulties, and visual spatial problems.4 Alzheimer’s disease is caused by abnormal accumulation of the proteins A-42 and abnormally phosphorylated tau in the brain, leading to neuronal dysfunction and death. A depletion of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine is also implicated in AD and contributes to the short-term memory and attention problems experienced by people with AD.

Alzheimer’s disease is slowly progressive, and residents with this condition will have difficulty managing daily activities primarily due to cognitive deficits. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a standardized and widely used tool to assess cognitive function. Individuals with AD typically lose several points each year, although this rate of decline may be affected by current treatments targeted at acetylcholine and glutamate.5-7

Most cases of AD occur in persons over the age of 65. Although only a few people in their mid-30s or -40s are diagnosed with AD, one in every ten persons over the age of 65 has the disease, and nearly one-half of the population age 85 years or older has AD.8 Estimates of survival have been dependent upon factors such as symptom onset, time of diagnosis, and individual patient characteristics. In a recent study, median survival in AD from onset of first symptom was 11.7 ± 0.6 years.9 Alzheimer’s disease is associated with affective, behavioral, and personality features. Depression may occur in the early stages of AD.10 Hart et al11 retrospectively studied behavioral symptoms in AD and made the following conclusions: behavioral symptoms in AD emerged, on average, at 48 months in the disease; the most common behavioral symptoms were apathy, motor disruption, aggression, irritability, appetite changes, and sleep disturbances; with the exception of apathy, behavioral symptoms waned over time. Social skills, the ability to interact gracefully with others, are often retained late into the disease.12

FRONTOTEMPORAL LOBAR DEGENERATION

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration is the third most common cause of degenerative dementia, ranking only behind AD and dementia with Lewy bodies. The incidence is probably higher due to problems in recognition and diagnosis.13 FTLD can be mistaken for a psychiatric or mood disorder.14

FTLD focally affects the frontal and/or anterior temporal lobes of the brain. These structures have an important role in regulating behavior, judgment, language, and personality. FTLD is characterized by profound behavioral and personality changes resulting from deterioration of the frontal and/or anterior lobes of the brain. Three clinical subgroups of FTLD have been identified: frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and two speech and language conditions, termed progressive non-fluent aphasia (PNFA) and semantic dementia (SD). Behavioral symptoms are present at disease onset in the FTD subgroup, and usually emerge in the two language subgroups. In FTD, behavioral symptoms such as apathy, disinhibition, and hyperorality often occur.15-19 In one study, social misconduct in the form of theft or offensive language occurred in nearly one-half of persons with FTLD.20 Individuals with FTLD often exhibit diminished empathy and concern for others.21 Core diagnostic criteria for FTLD include personality changes such as emotional blunting and lack of insight.22

Patients with SD exhibit a loss of knowledge of the meaning of words and objects. While the person with AD may have trouble finding the right word, the person with SD may be perplexed when confronted with a common object or phrase, stating, “I don’t know what this is” or “I don’t know what you mean by that.” Behavioral symptoms, such as rigidity, stubbornness, self-centeredness, and adoption of compulsive rituals, typically occur with disease progression.

People with PNFA demonstrate a diminished ability to produce speech, and progressive difficulty with writing and reading. Mutism eventually occurs. In our clinical experience, patients with PNFA remain more functionally intact than patients with other subtypes. Many of our patients with PNFA are independent in instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), despite profound aphasia. Emergence of behavioral symptoms occurs more slowly in PNFA when compared to the behavioral subtype of FTLD.23

The average age for first symptoms in FTLD is 56 years.24 Survival is typically shorter with the FTLD subgroups, with the possible exception of SD where the duration of illness is similar to AD.9

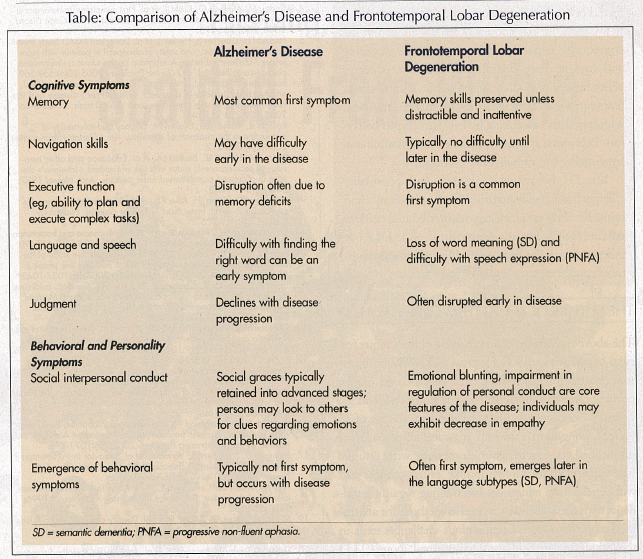

People in the earlier stages of FTLD, as compared to AD, often achieve higher scores on the MMSE at baseline.25 Despite the higher cognitive scores, those with FTLD demonstrate profound deficits in their ability to manage day-to-day activities. These functional losses of FTLD are secondary to judgment problems and behavioral symptoms, in contrast to the memory deficits of AD. Most people with FTLD, especially when behavioral symptoms exist, have difficulty engaging in occupational or family pursuits. There may be financial problems due to the affected person’s job loss, bad investments, or overspending.26 The Table summarizes the major differences between these two types of dementia.

THE PROGRESSION TO LONG-TERM CARE

The following case histories further illustrate the differences between FTLD and AD, and describe the unique challenges in meeting the long-term care needs of people with FTLD.

Case History of an Individual Diagnosed with AD

Mr. K was seen at the age of 55 for evaluation of memory loss that had begun approximately five years earlier. His family noted that he had difficulty remembering dates and appointments. The loss was progressive, and other symptoms, such as getting lost in familiar places, trouble with calculations, and difficulty remembering names, gradually emerged. Word-finding difficulty and trouble completing full sentences became more pronounced. Functionally, Mr. K became unable to maintain his checkbook, cook, or sustain his job. He was able to take long walks and continued to play tennis and golf. Behaviorally, Mr. K demonstrated some mild apathy and was treated for depression. His MMSE score at initial evaluation was 17/30 with deficits in memory, orientation, naming, and visual spatial tasks. He was pleasant, warm, and delightful at the time of his initial evaluation and on subsequent clinic visits. Over time, Mr. K’s cognitive deficits progressed; he spoke only a few words at a time, and he demonstrated significant memory loss. Functionally, he was dependent in all IADLs (ie, cooking, shopping, bill paying, etc) and needed assistance with dressing himself and personal hygiene. When his care needs became too much for his family to manage safely at home, he moved to a long-term care facility.

Case History of an Individual Diagnosed with FTD

Mr. D was referred for evaluation at the age of 47 for complaints of short-term memory loss, although his history revealed changes in both personality and behavior. Family members described his prior personality as warm, gregarious, sensitive, and generous. His initial symptoms were diminished interest and empathy with regard to family matters. Several years into Mr. D’s condition, he began engaging in ritualistic behaviors, such as playing solitaire on his computer for extended periods of time, counting cars while driving, and playing the “alphabet game” using license plates. He was laid off due to downsizing of his company, but he did not seek new employment. After approximately five years, he was noticeably less organized and less emotionally responsive. Mr. D’s personal grooming and hygiene were declining. There were concerns about his ability to safely supervise his child. The next few years were characterized by increasing emotional withdrawal and increasing bizarre, stereotyped behaviors. Behavioral symptoms included disinhibition and hyperorality (eg, carbohydrate cravings). Mr. D’s behavioral symptoms and personality changes had a highly negative effect on his family and home life. He was ultimately transferred to a residential care facility. He was dependent in all IADLs, but independent in basic self-care. His behavioral symptoms continued to be a challenge in his care.

THE FUTURE OF LONG-TERM CARE FOR FTLD

The above case studies illustrate some of the unique features of patients with FTLD versus AD. While both persons eventually required long-term care, their reasons for needing care were different. Nursing home residents are typically Caucasian, widowed females over the age of 75 years.27 Long-term care staff may feel unprepared or unqualified to care for younger persons with unusual behavior and personality symptoms. Nursing home staff will benefit from education and training regarding residents with these disorders, as well as methods for accommodating them safely. Tremendous challenges exist in the long-term care field as more is learned about FTLD and appropriate interventions are developed.

This work was supported by the following grants: 1 P50 AG-03-006-01 NIH/NIA—Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers, Core A and Core B; 5 P01 AG019724-02 FTD PPG—Frontotemporal Dementia: Genes, Images and Emotions, Core A and Project 4; and The Larry Hillblom Foundation, Grant #2002/2F, Hillblom Network Program.