Assessing Pain in Older Adults with Dementia

Alzheimer’s Association

Best Practices in Nursing Care for Hospitalized Older Adults with dementia

from The John A. Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing and the Alzheimer’s Association

Issue Number D2, Revised 2007

Series Editor: Marie Boltz, MSN, APRN, BC, GNP

Managing Editor: Sherry A. Greenberg, MSN, APRN, BC, GNP

New York University College of Nursing

WHY:

There is no evidence that older adults with dementia physiologically experience less pain than do other older adults (American Geriatrics Society (AGS), 2002). Rather than being less sensitive to pain, cognitively-impaired elders may fail to interpret sensations as painful, are often less able to recall their pain, and may not be able to verbally communicate it to care providers (AGS, 2002). As such, cognitively impaired older adults are often under-treated for pain.

As with all older adults, those with dementia are at risk for multiple sources and types of pain, including chronic pain from conditions such as osteoarthritis and acute pain. Untreated pain in cognitively impaired older adults can delay healing, disturb sleep and activity patterns, reduce function, reduce quality of life, and prolong hospitalization.

BEST TOOLS:

Several tools are available to measure pain in older adults with dementia. Few have been comprehensively evaluated and each has strengths and limitations (Herr, Decker, & Bjoro, 2006). The American Medical Directors Association has endorsed the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale (PAINAD) (Warden, et al, 2003).

We recommend the following:

• Ask older adults with dementia about their pain. Even older adults with mild to moderate dementia can respond to simple questions about their pain (American Geriatrics Society, 2002).

• Use a standardized tool to assess pain intensity, such as the numerical rating scale (NRS) (0-10) or a verbal descriptor scale (VDS) (Herr, 2002; See also Try This: Pain Assessment). The VDS asks participants to select a word that best describes their present pain (e.g., no pain to worst pain imaginable) and may be more reliable than the NRS in older adults with dementia.

• Use an observational tool (e.g., PAINAD) to measure the presence of pain in older adults with dementia.

• Ask family or usual caregivers as to whether the patient’s current behavior (e.g., crying out, restlessness) is different from their customary behavior. This change in behavior may signal pain.

• If pain is suspected, consider a time-limited trial of an appropriate type and dose of an analgesic agent. Thoroughly investigate behavior changes to rule out other causes. Use the PAINAD to evaluate the pain before and after administering the analgesic.

TARGET POPULATION:

Older adults with cognitive impairment who cannot be assessed for pain using standardized pain assessment instruments. Pain assessment in older adults with cognitive impairment is essential for both planned or emergent hospitalization.

VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY:

The PAINAD has an internal consistency reliability ranging from .50 (for behavior assessed at rest) to .67 (for behaviors assessed during unpleasant caregiving activities). Interrater reliability is high (r - .82 - .97). No test-retest reliability is available.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS:

Pain is a subjective experience and there are no definitive, universal tests for pain. For patients with dementia, it is particularly important to know the patient and to consult with family and usual caregivers.

BARRIERS to PAIN MANAGEMENT in OLDER ADULTS with DEMENTIA:

There are many barriers to effective pain management in this population. Some common myths are: pain is a normal part of aging; if a person doesn’t verbalize that they have pain, they must not be experiencing it; and that strong analgesics (e.g., opioids) must be avoided. An effective approach to pain management in older adults with dementia is to assume that they do have pain if they have conditions and/or medical procedures that are typically associated with pain. Take a proactive approach in pain assessment and management.

MORE ON THE TOPIC:

Best practice information on care of older adults: www.GeroNurseOnline.org.

American Geriatrics Society Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons. (2002). Clinical practice guidelines: The management of persistent pain in older persons. JAGS, 50, S205-S224. Available at the American Geriatrics Society Web site, www.americangeriatrics.org.

Herr, K. (2002). Pain assessment in cognitively impaired older adults. AJN, 102(12), 65-68.

Herr, K., Bjoro, K., & Decker, S. (2006). Tools for assessment of pain in nonverbal older adults with dementia: A state-of-the-science review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 31(2), 170-192.

Warden, V., Hurley, A.C., & Volicer, L. (2003). Development and psychometric evaluation of the pain assessment in advanced dementia (PAINAD) Scale. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 4(1), 9-15.

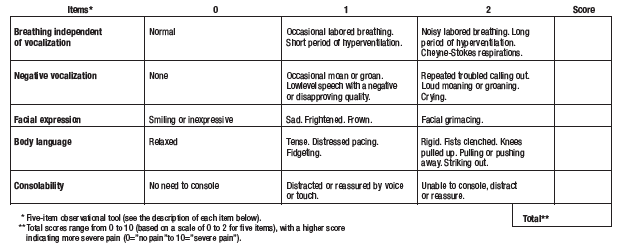

Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) Scale

BREATHING

1. Normal breathing is characterized by effortless, quiet, rhythmic (smooth) respirations.

2. Occasional labored breathing is characterized by episodic bursts of harsh, difficult or wearing respirations.

3. Short period of hyperventilation is characterized by intervals of rapid, deep breaths lasting a short period of time.

4. Noisy labored breathing is characterized by negative sounding respirations on inspiration or expiration. They may be loud, gurgling, or wheezing. They appear strenuous or wearing.

5. Long period of hyperventilation is characterized by an excessive rate and depth of respirations lasting a considerable time.

6. Cheyne-Stokes respirations are characterized by rhythmic waxing and waning of breathing from very deep to shallow respirations with periods of apnea (cessation of breathing).

NEGATIVE VOCALIZATION

1. None is characterized by speech or vocalization that has a neutral or pleasant quality.

2. Occasional moan or groan is characterized by mournful or murmuring sounds, wails or laments. Groaning is characterized by louder than usual inarticulate involuntary sounds, often abruptly beginning and ending.

3. Low level speech with a negative or disapproving quality is characterized by muttering, mumbling, whining, grumbling, or swearing in a low volume with a complaining, sarcastic or caustic tone.

4. Repeated troubled calling out is characterized by phrases or words being used over and over in a tone that suggests anxiety, uneasiness, or distress.

5. Loud moaning or groaning is characterized by mournful or murmuring sounds, wails or laments much louder than usual volume. Loud groaning is characterized by louder than usual inarticulate involuntary sounds, often abruptly beginning and ending.

6. Crying is characterized by an utterance of emotion accompanied by tears. There may be sobbing or quiet weeping.

FACIAL EXPRESSION

1. Smiling is characterized by upturned corners of the mouth, brightening of the eyes and a look of pleasure or contentment. Inexpressive refers to a neutral, at ease, relaxed, or blank look.

2. Sad is characterized by an unhappy, lonesome, sorrowful, or dejected look. There may be tears in the eyes.

3. Frightened is characterized by a look of fear, alarm or heightened anxiety. Eyes appear wide open.

4. Frown is characterized by a downward turn of the corners of the mouth. Increased facial wrinkling in the forehead and around the mouth may appear.

5. Facial grimacing is characterized by a distorted, distressed look. The brow is more wrinkled as is the area around the mouth. Eyes may be squeezed shut.

BODY LANGUAGE

1. Relaxed is characterized by a calm, restful, mellow appearance. The person seems to be taking it easy.

2. Tense is characterized by a strained, apprehensive or worried appearance. The jaw may be clenched (exclude any contractures).

3. Distressed pacing is characterized by activity that seems unsettled. There may be a fearful, worried, or disturbed element present. The rate may be faster or slower.

4. Fidgeting is characterized by restless movement. Squirming about or wiggling in the chair may occur. The person might be hitching a chair across the room. Repetitive touching, tugging or rubbing body parts can also be observed.

5. Rigid is characterized by stiffening of the body. The arms and/or legs are tight and inflexible. The trunk may appear straight and unyielding (exclude any contractures).

6. Fists clenched is characterized by tightly closed hands. They may be opened and closed repeatedly or held tightly shut.

7. Knees pulled up is characterized by flexing the legs and drawing the knees up toward the chest. An overall troubled appearance (exclude any contractures).

8. Pulling or pushing away is characterized by resistiveness upon approach or to care. The person is trying to escape by yanking or wrenching him or herself free or shoving you away.

9. Striking out is characterized by hitting, kicking, grabbing, punching, biting, or other form of personal assault.

CONSOLABILITY

1. No need to console is characterized by a sense of well being. The person appears content.

2. Distracted or reassured by voice or touch is characterized by a disruption in the behavior when the person is spoken to or touched. The behavior stops during the period of interaction with no indication that the person is at all distressed.

3. Unable to console, distract or reassure is characterized by the inability to sooth the person or stop a behavior with words or actions. No amount of comforting, verbal or physical, will alleviate the behavior.

Reprinted from Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 4(1), 9-15. Warden, V., Hurley, A.C., & Volicer, L. Development and psychometric evaluation of the pain assessment in advanced dementia (PAINAD) Scale.

Copyright (2003), with permission from American Medical Directors Association.

Permission is hereby granted to reproduce, post, download, and/or distribute, this material in its entirety only for not-for-profit educational purposes only, provided that The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing, College of Nursing, New York University is cited as the source. This material may be downloaded and/or distributed in electronic format, including PDA format. Available on the internet at www.hartfordign.org and/or www.GeroNurseOnline.org. E-mail notification of usage to: hartford.ign@nyu.edu.

A SERIES PROVIDED BY The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing EMAIL: hartford.ign@nyu.edu HARTFORD INSTITUTE WEBSITE: www.hartfordign.org GERONURSEONLINE WEBSITE: www.GeroNurseOnline.org