Arbitration and Mediation: Finding Your Organization’s Optimal Approach

ECRI Institute and Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging (ALTC) have joined in collaboration to bring ALTC readers periodic articles on topics in risk management, quality assurance and performance improvement (QAPI), and safety for persons served throughout the aging services continuum. ECRI Institute is an independent nonprofit that researches the best approaches to improving health care.

The right to a jury trial as a means of resolving civil disputes is enshrined in the Seventh Amendment to the US Constitution. However, the perceived shortcomings of litigation have resulted in increasing use of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms, such as arbitration and mediation.

Simply using arbitration agreements or mediation processes does not mean that ADR will be effective. Courts can refuse to enforce binding arbitration agreements if, for example, the agreement process or the terms are unfair or if the signer does not have authority to bind the resident to the agreement. Similarly, mediation can break down if the parties or their liability insurers do not commit to the process and its goals.

Aging services providers that choose to use mediation, arbitration, or both can optimize their approach by understanding available options and protections for ADR and designing a system that fits their culture and claims philosophy, as well as their jurisdiction’s liability climate.

Arbitration

Arbitration, unlike mediation, is an adversarial process whereby the parties submit information about the controversy to an arbitrator or panel of arbitrators that renders a decision. Contracts may provide for ADR in a private forum, as individuals and entities may agree in advance to arbitration in the event of a dispute. In 2012, the US Supreme Court upheld a provision in a nursing home (NH) admission contract that called for binding arbitration of all disputes “other than claims to collect late payments owed by the patient.”1 In that case, the high court held that the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) preempts conflicting state policy or state law that prohibits arbitration.

Arbitration may be nonbinding or binding. In binding arbitration, the parties agree that the decision is final and may be enforced in judicial proceedings. The FAA and state laws provide a very limited right of “appeal” to the courts to vacate or modify binding arbitration decisions, for reasons such as lack of fairness or process integrity, fraud, or corruption. The rules of some private arbitration organizations allow for “appeals” to the organizations’arbitration tribunals.2

In June 2017, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a proposed rule outlining several requirements that would apply to all agreements for binding arbitration in NHs, whether formed before or after a dispute.3 As of this writing, CMS has not issued a final rule. And as of June 2018, 21 states and the District of Columbia had adopted the Revised Uniform Arbitration Act (RUAA), which takes effect July 1, 2019. The RUAA replaces the original Uniform Arbitration Act, which was promulgated in 1956, and addresses several issues that arise in modern arbitration that were unaddressed in the original act.4 NHs should remain alert for a final rule from CMS, and aging services providers in states that have adopted the RUAA should ensure that their arbitration agreements and processes comply with the new law.

Mediation

Mediation is a nonadversarial process that uses a less formal approach in which the parties control the outcome. Some jurisdictions require “compulsory mediation” before any case can be tried. However, mediation works best when the parties commit to achieving a mutually agreeable resolution rather than having mediation imposed on them.5 Engaging in mediation does not preclude the use of arbitration or the courts for unresolved issues.

Mediation is facilitated by a trained, neutral mediator with knowledge and experience in the substantive area of the dispute. The mediator helps parties communicate the basis of the dispute, identify their interests and needs, and reach a resolution based on their expectations and needs rather than their “rights.” Mediators also help the parties to think creatively about “win-win” approaches that parties locked in battle may be unable to perceive.6 Mediation may work synergistically with an organization’s safety culture programs, particularly those that include disclosure, apology, and early offers of settlement. In addition, information that comes to light during mediation may help providers and injured residents and their families to work together to develop programs that can prevent similar occurrences.

Identifying ADR Programs

As a first step in deciding how to approach ADR, organizations should identify programs that are available in their jurisdictions. Many states provide court-appended ADR programs for the resolution of civil disputes generally; increasingly, states are implementing or considering ADR programs specifically for resolving medical negligence cases. Some medical negligence ADR programs are court-appended; others are not court-appended but provide statutory protections for early discussions and offers.

The elements of ADR programs vary considerably among jurisdictions. Some jurisdictions require mandatory early settlement conferences or case evaluation, whereas others require mandatory but nonbinding arbitration or attempts at mediation before a case can proceed to trial. Other states offer ADR programs that are voluntary but receive special protections. For example, some mediation and early settlement programs work in tandem with state apology laws.

With funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) Patient Safety and Medical Liability Initiative, several states implemented demonstration projects or planning grants that linked liability reform with patient safety.7 AHRQ’s website describes the 13 planning grants and 7 demonstration projects included in the initiative.8 Evaluation of the AHRQ-funded programs remains under way, but early reports and observations about several of the programs suggest their success.

Implementing an ADR Policy

Organizations in jurisdictions without a court-appended ADR program in place may wish to consider developing a policy for mediation or predispute binding arbitration in a private forum. As more data and reports become available from institutions that have participated in ADR and from AHRQ-funded projects, risk managers can identify programs and program elements that may be a good fit with their organization’s claims philosophy and culture of patient safety and the jurisdiction’s climate of liability.

Organizations insured by commercial insurers must enlist the full cooperation and agreement of professional liability insurer(s) to resolve covered claims through ADR. As is evident in some AHRQ-funded medical liability projects, professional liability insurers may assume an integral role in an organization’s programs that incorporate disclosure, apology, and early offers of settlement by providing training in disclosure and apologies, particularly in jurisdictions that provide some measure of legal privilege for statements of apology.

Consider Arbitration Agreements

Organizations that decide upon arbitration as the preferred mechanism for resolving disputes should ensure that a predispute binding arbitration agreement is prepared that reflects the organization’s rationale and goals of arbitration (eg, the organization has a preference for arbitration because the process may be speedier and less disruptive to the parties than formal litigation and trial).

Taking the actions listed in Box 1 can help reduce the risk of a legal challenge to a predispute binding arbitration agreement.

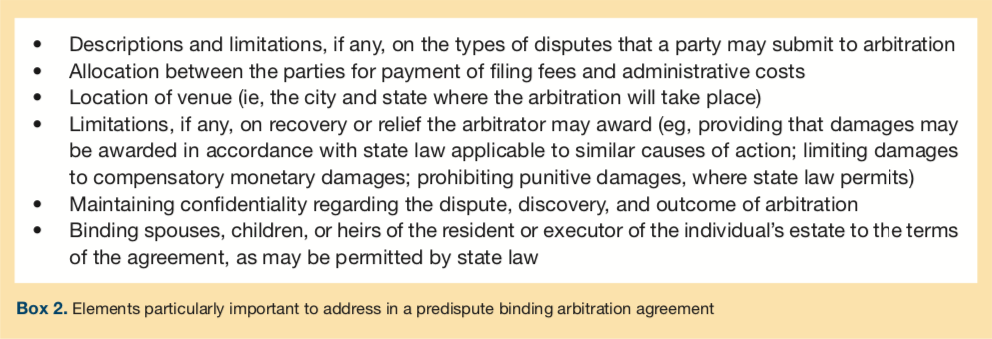

To avoid ambiguity, risk managers should consult with legal counsel to ensure that the agreement appropriately addresses the elements outlined in Box 2.

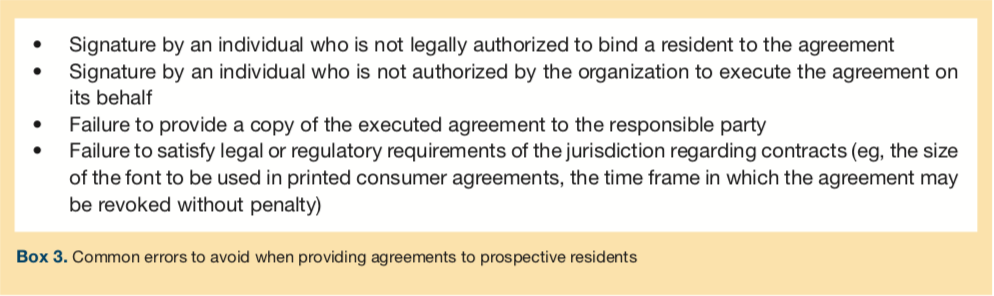

The protocol for providing the agreements to prospective residents should avoid common errors that could cause the agreements to be voided by a court (Box 3).

Consider Mediation

In some jurisdictions, the parties to a medical negligence lawsuit must participate in an initial mediation session and afterward can decide whether to continue participation.9 Court-appended mediation in some jurisdictions has met with little success in resolving malpractice claims. Administrative inefficiency, lack of cooperation by insurers, and procedural maneuvers on the part of trial attorneys are cited as factors impeding the success of mediation.10

In the absence of a court-appended mediation program, mediation may be conducted privately. The following are some questions that the parties should consider when deciding whether to mediate a dispute 11:

• What is the conflict really about?

• Are there issues or facts that the parties already agree on?

• What do you want the mediator to understand?

• What is your goal for the outcome of the mediation?

• What would make you feel satisfied with the outcome?

• What are your best and worst alternatives if an agreement is not achieved through mediation?

Conclusion

Because ADR generally resolves disputes in less time than it takes to get to trial, the parties can avoid prolonged “litigation stress” and minimize the polarizing effects of trial on the parties. Lack of confidence in the competence of jurors as fact finders, unpredictability in jury verdicts, high legal defense costs, excessive damage awards, and costs of appeals from verdicts and judgments are considerations that also favor ADR. ADR may be implemented before, during, or after litigation. Court-appended pretrial ADR is available in many jurisdictions and offers opportunities for litigants to resolve disputes short of full-blown trials. υ

References

1. Marmet Health Care Ctr, Inc, v Brown, 132 U.S. 1201 (2012).

2. American Arbitration Association (AAA). Optional appellate arbitration rules. https://www.adr.orghttps://s3.amazonaws.com/HMP/hmp_ln/imported/AAA%20ICDR%20Optional%20Appellate%20Arbitration%20Rules.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed January 3, 2019.

3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare and Medicaid programs; revision of requirements for long-term care facilities: arbitration agreements [proposed rule]. Fed Regist. 2017;82(109):26649-26653.

4. Yusem SG, Pepe RP. Pa. adopts Revised Uniform Arbitration Act: resolves ambiguities, conflicts. The Legal Intelligencer. July 6, 2018. https://www.law.com/thelegalintelligencer/2018/07/06/pa-adopts-revised-uniform-arbitration-act-resolves-ambiguities-conflicts/. Accessed January 3, 2019.

5. Lanier EC. What is quality in elder care mediation and why should elder care advocates care? ABA Bifocal. 2010;32(2):15-19.

6. Sybblis S. Mediation in the health care system: creative problem solving. Pepperdine Dispute Resolut Law J. 2006;6(3):493-517.

7. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Advances in patient safety and medical liability. https://www.ahrq.govhttps://s3.amazonaws.com/HMP/hmp_ln/imported/publications/files/advances-complete_3.pdf. Published August 2017. Accessed January 3, 2019.

8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Medical Liability Reform and Patient Safety Initiative Progress Report. archive.ahrq.gov website. https://archive.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/patient-safety-resources/resources/liability/medliabrep.html. Published September 2012. Updated February 2012.

Accessed January 3, 2019.

9. Hyman CS, Liebman CB, Schechter CB, Sage WM. Interest-based mediation of medical malpractice lawsuits: a route to improved patient safety? J Health Polit Policy Law. 2010;35(5):797-828. doi:10.1215/03616878-2010-028

10. Spivak C. Medical mediation rarely provides closure for families. Milwaukee Wis J Sentinel. August 9, 2014. https://www.jsonline.com/watchdog/watchdogreports/medical-mediation-doesnt-always-provide-closure-for-families-b99324156z1-270618031.html. Accessed January 3, 2019.

11. American Bar Association (ABA). Preparing for complex civil mediation. https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/images/dispute_resolution/Mediation_Guide_Complex.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed January 3, 2019.