Cultural Implications for Assessment and Treatment of Depression in Hispanic Elderly Individuals

Hispanic elderly are the fastest growing older population segment, and they will outpace all other ethnic elder groups during the 21st century.1 The term Hispanic can be misleading, suggesting connections to Spain when the majority of Hispanics in the United States are from Latin America. The Spanish language is a common denominator of many Hispanic elderly persons, while the culture, life experiences, socioeconomic status, and the dialect of Spanish can be vastly different among Hispanic elderly individuals. Many Hispanics are U.S. immigrants, while others, such as New Mexico Hispanics, arrived in what is now New Mexico prior to 1600. Caribbean immigrants may be of African and Spanish ancestry, utilizing a rapid dialect of Spanish. Other Hispanic elderly may have personally survived physical torture and/or witnessed family death in Latin American countries undergoing political strife. Others may identify predominantly with European ancestry, while still others may speak indigenous Indian languages.

Epidemiology of Depression in Hispanic Elderly

Research on the prevalence of depression in Hispanic elderly is limited in quantity, and the results are mixed. Studies of non-immigrant Hispanics have demonstrated a higher incidence of depressive symptoms in Hispanic women, but no differences in men.2 Another report states that immigrant Hispanics are more at risk than non-immigrants.3 Some reports suggest lower rates of depression in immigrant Hispanics as compared to Hispanics who have lived longer in the United States. The prevalence of depression in Hispanic immigrants as compared to Hispanic non-immigrants may also depend on the region or community. In one study in Fresno, California, depression was less likely in immigrants from Mexico as compared to U.S.-born Mexicans.4 Another study in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas demonstrated increased risk of depression in immigrant Mexicans.5 A single study that examined antidepressant use in elderly Mexican Americans found that this group was less likely to be prescribed the antidepressants, and 50% of the time they were prescribed tricyclic antidepressants, which pose serious risks.6

Major depression and dysthmia (milder, but chronic depression) occur in 5% to 10% of all elderly persons seen in primary care clinics.7 In a Sacramento study of Mexican elderly, it was found that depressive symptoms were present in 32% of elderly Mexican women and 16% of elderly Mexican men.3 A study of New Mexico elderly persons found a depression rate higher in Hispanic elderly than non-Hispanic white elderly, with the highest rate noted in elderly Hispanic women.8

Contributory Factors

A number of economic, political, and health issues should be considered in treating depression in Hispanic elderly individuals. Socioeconomic issues such as family income, limited education, and inability to speak English all limit the availability of healthcare resources, as well as the ability to negotiate large healthcare centers. The majority of older Hispanics are Spanish-dominant, have a low income, and have less than a high school education.9 Some understanding of the political experiences of immigrant elderly may help to understand mood difficulties. Immigrants from Guatemala, El Salvador, Chile, Argentina, Cuba, and other countries where political violence has occurred may have experienced torture, or family death or brutality. These individuals are at high risk for developing post-traumatic stress disorder, with patients experiencing nightmares, intrusive memories of the traumatic event, and fearfulness, as well as depression.

All chronic medical conditions often can contribute to a secondary depression. Chronic pain, immobility, or impending death can all cause secondary depression. Medical conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, cerebrovascular accidents, diabetes mellitus, and declining cognition or early Alzheimer’s disease are all associated with increased depressive symptoms. Alternately, chronic depression can contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease.10 Diabetes and hypertension both occur more often in Hispanic elderly. Elderly Hispanic persons with diabetes are more likely to experience depression than elderly Hispanics without diabetes, and those with diabetes and depression have a far greater utilization of healthcare resources.11 A survey of elderly Hispanics with diabetes demonstrated that 31% of these individuals suffered from depression. Stroke rates in Hispanics are higher than in non-Hispanic white individuals.12 A common outcome of stroke is depression, especially with strokes occurring in the left-frontal brain.13 Furthermore, treatment for depression in elderly persons may improve their functional status and self-care, in addition to their mood.14

Assessment of Depression

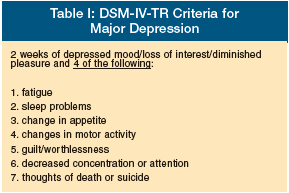

The assessment of depression requires inquiring about mood as well as sleep, appetite, energy, pleasure in life, and suicidality if depressive symptoms are present (Table I).

The assessment of depression requires inquiring about mood as well as sleep, appetite, energy, pleasure in life, and suicidality if depressive symptoms are present (Table I).

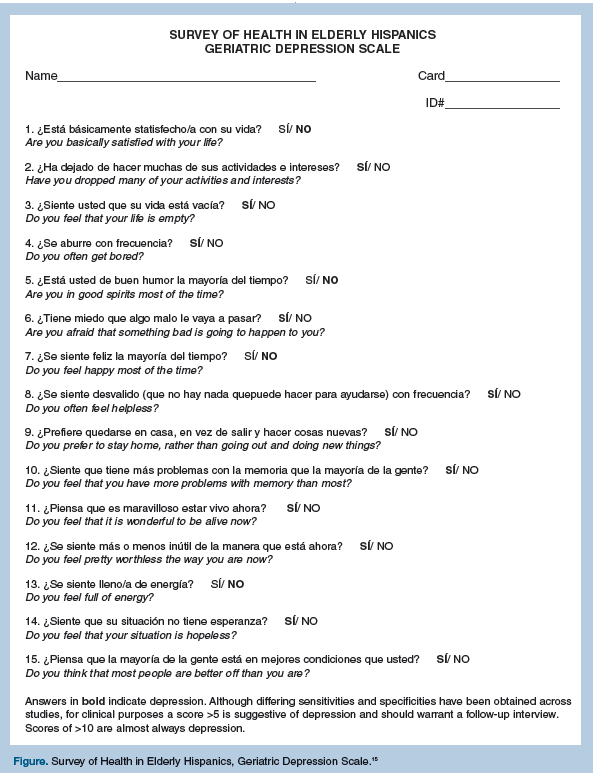

Screening instruments for depression can provide important guidance for clinical interviewing. However, screens should be sensitive to the language dialect and the culture of the patient. Translating standardized screening instruments requires translation, back translation, and then testing. The “Survey of Health in Hispanic Elderly,” a translation of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS),15 was developed with elderly Hispanic individuals in New Mexico. It was translated from the GDS-Short Form by a committee of seven members, with the back translated by three community members to ensure that Spanish comprehension and meaning was preserved (Figure).

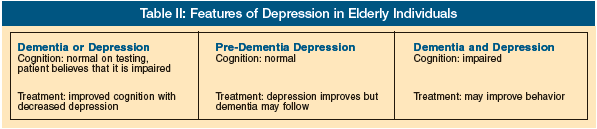

The clinical evaluation of all elderly persons should include some measure of evaluation of cognitive function. This provides the clinician with an understanding of whether the depression is associated with a dementia (Table II). Most cognitive screening tests are educationally biased. Even the commonly used Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is educationally biased; however, by using education-adjusted scores, some correction can be made.16,17 A more culture- and education-neutral, quick cognitive screen is the Clock Drawing Test, in which the patient is instructed to draw a clock with the numbers and hands on the face at specific times.18 This test can easily be performed in Spanish and is less affected by education in determining cognitive impairment or dementia. Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) are another important measure in assessing older patients, as functional status in older people may be compromised by chronic illness or dementia.

Cultural Issues in Treating Hispanic Elderly

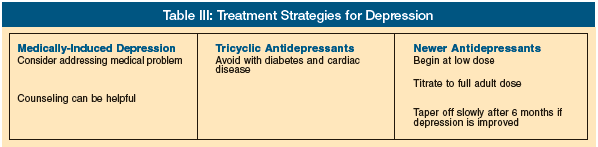

If the depression is caused by chronic medical conditions or is a side effect of a medication for a medical condition, addressing these problems may eliminate the need for additional medication. Mild depression and dysthymia may not require antidepressant treatment; however, major depression warrants treatment consideration (Table III).

Psychotherapy, which may involve individual, group, or family modalities, is effective in the older person. This can be particularly effective for the older individual with depression who refuses or cannot tolerate an antidepressant. Improvement will occur more rapidly when antidepressant treatment is combined with psychotherapy. However, only 9.5% of elderly Hispanics with depression receive psychotherapy, and 33% receive antidepressants.19

Included in the revised Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) are the cultural variations in the clinical presentation of depression. Hispanic individuals often come to clinicians complaining of problems with “nervios” or nerves.20 The DSM-IV-TR describes the importance of understanding the context of idioms that may be used to describe depressive symptoms.

Spiritual and familial issues may be important to Hispanic elderly. Familismo or familialism is a family-centered life common to many Hispanics. Inclusion of family members should be at the discretion of the elderly individual. Some Hispanic elderly do not want their grown children or grandchildren participating in their healthcare. Others—and certainly those with dementia or cognitive impairment—will require family assistance and support to carry out any treatment plan. Religious participation may also affect depression treatment in the older person. Supporting the older individual’s desire for consultation with a priest, minister, or other spiritual advisor may enhance patient collaboration.

One caution in the assessment of Spanish-speaking patients by non–Spanish-speaking clinicians is the use of family members as interpreters. Family members can minimize or exaggerate depressive symptoms in the elderly person, and they may try to clue them about questions regarding cognitive knowledge. A Spanish-speaking staff member is generally more effective in providing interpretation for the assessment of depression and dementia.

Finally, using open-ended questions to understand the older individuals’ explanatory model for why they believe that they are experiencing sadness and depression, and further inquiry about what they believe is the needed treatment, may provide the clinician with the best direction in selecting treatment for the Hispanic elderly individual with depression.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.